|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Case Report |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

|

|

|

Vivek Mangla1, Sujoy Pal1, Nihar Ranjan Dash1, Prasenjit Das2, Vineet Ahuja3, Atul Sharma4, Peush Sahni1, Tushar Kanti Chattopadhyay1

Departments of Gastrointestinal Surgery,1 Pathology,2

Gastroenterology,3 and Medical Oncology,

Institute Rotary Cancer Hospital,4

All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Vivek Mangla

Email: mangla.vivek@gmail.com

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.2012.55

48uep6bbphidvals|540 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Primary colorectal lymphoma is a rare disease primarily affecting the elderly population and accounts for 0.2-0.6% of all colorectal malignancies.[1] There is an increase in incidence of non- Hodgkin’s lymphoma in patients with inflammatory bowel disease on immunosuppressive therapy but the overall risk is low.[2]

Rectal mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma in the setting of ulcerative colitis is rare. Consequently, there is lack of adequate information regarding the appropriate management of rectal MALT lymphoma in patients with ulcerative colitis. We report a case of rectal MALT lymphoma in a young patient with ulcerative colitis in whom the diagnosis of MALT lymphoma was made after restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch anal anastomosis done for steroid refractory disease.

Case report

A 19-year-old girl presented with a history of recurrent episodes of diarrhoea with passage of blood and mucus in the stools for the past 3 years. A colonoscopy done at that time showed presence of ulcerations and pseudopolyps throughout the colon and rectum. Colonic biopsy showed glandular disarray, cryptitis, mucus and crypt depletion which were compatible with ulcerative colitis. She was started on mesalamine but soon required high dose corticosteroids. Since then she had been on steroids and these could not be tapered despite multiple attempts. She also had had one episode of severe respiratory tract infection requiring hospitalization and treatment with parenteral antibiotics. During her present admission to the hospital she had mild pallor and per rectal examination revealed blood on the finger but no mass lesion was felt.

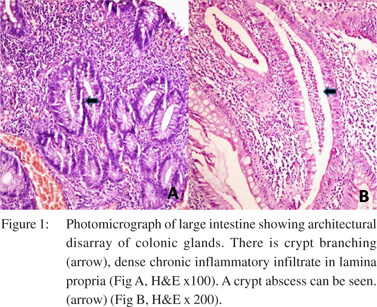

As she had steroid dependent disease she was counselled regarding the surgical management. A 3-stage proctocolectomy and ileal pouch–anal anastomosis was planned as she was on high dose steroids. She had a subtotal colectomy with an end ileostomy and Hartmann’s procedure as the first stage. Histology showed disarray of glandular architecture with crypt branching. Cryptitis and crypt abscesses were present. Lamina propria was infiltrated by a moderately dense infiltrate of chronic lympho-plasmacytic cells admixed with polymorphs (Figure 1) confirming the diagnosis of ulcerative colitis. Postoperatively her steroids were tapered and stopped over a period of two months. She had occasional bleeding per rectum which was managed with mesalamine suppositories. After 3 months, she had the second stage procedure, involving removal of the rectal stump and an ileal J-pouch–anal anastomosis with a diverting loop ileostomy. Gross examination of the rectal stump showed extensive ulceration in the rectal mucosa but no mass.

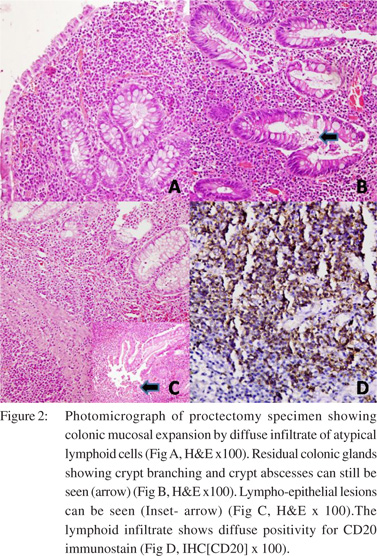

To our surprise, the histological evaluation of the proctectomy specimen showed expansion of mucosa by a dense infiltrate of atypical lymphoid cells, admixed with few plasma cells and occasional lymphoid follicles. There were few atypical mitotic figures and apoptotic bodies. These lymphoid cells were found to infiltrate and destroy the colonic glands. Infiltration into submucosa was also noted (Figure 2).

Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining revealed that the lymphoid cells were positive for CD20 (B cell marker) and negative for CD30, CD10, CD5 and cyclin-D1. The cut margins were free of disease. Two lymph nodes retrieved from the specimen also showed similar changes.

Based on the morphology and IHC staining, a diagnosis of rectal MALT lymphoma in a background of ulcerative colitis was made. Repeat clinical examination did not reveal any peripheral lymphadenopathy. The peripheral blood smear was normal. CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis detected no lesion. The patient then received four cycles of CHOP (Cyclophosphamide, Adriamycin, Vincristine and Prednisolone) chemotherapy without significant toxicity. A month after completion of chemotherapy, a contrast study was done to confirm the integrity of the ileal pouch–anal anastomosis and the ileostomy was closed.

Based on the morphology and IHC staining, a diagnosis of rectal MALT lymphoma in a background of ulcerative colitis was made. Repeat clinical examination did not reveal any peripheral lymphadenopathy. The peripheral blood smear was normal. CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis detected no lesion. The patient then received four cycles of CHOP (Cyclophosphamide, Adriamycin, Vincristine and Prednisolone) chemotherapy without significant toxicity. A month after completion of chemotherapy, a contrast study was done to confirm the integrity of the ileal pouch–anal anastomosis and the ileostomy was closed.

The patient has since been followed every three months with a clinical examination and endoscopic evaluation of the pouch. Follow-up CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis at 6 and 12 months did not reveal any evidence of recurrence. Over the subsequent 12 months the patient has remained well and has good pouch function with no evidence of recurrence of lymphoma.

Discussion

Immunosuppression and inflammatory bowel disease are considered as risk factors for colorectal lymphomas even though a direct causal link has never been established.[1,3,4] Primary rectal lymphoma in patients with ulcerative colitis receiving 6-mercaptopurine[4] azathioprine[5] and cyclosporine[6] has been reported. Of 45 cases of primary colorectal lymphoma reported by Shepherd et al,[7] only seven had a history of ulcerative colitis.

A majority of colorectal lymphomas are of the non- Hodgkin’s, diffuse large B cell variety. About one-third to onehalf of reported colorectal lymphomas are MALT type, commonly affecting the cecum, with rectum being an unusual site.[8,9] Rarely, large T-cell,[10] mixed B cell and T cell[11] and NK/Tcell[12] lymphoma have also been reported. In a review of 34 cases of rectal MALT lymphoma none had underlying ulcerative colitis.[9] None of the patients was less than 30 years of age. The lesions were polypoid and were diagnosed by endoscopic biopsy unlike our patient where the presence of MALT lymphoma was masked by the presence of ulcerations and pseudopolyps due to ulcerative colitis.

Cases of lymphoma masquerading as steroid refractory inflammatory bowel disease have also been reported.[11,13] There may be difficulty in detecting lymphoma in the presence of chronic inflammation associated with ulcerative colitis. It has been suggested that a biopsy revealing extensive lymphocytic infiltration should raise the suspicion of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.[14] In our patient, changes of ulcerative colitis were present throughout the colon without evidence of any lymphoma initially. This was confirmed twice, once on colonoscopic biopsy and again on complete histological evaluation of the subtotal colectomy specimen. The rectal lymphoma was detected only in the proctectomy specimen.

This suggests that both ulcerative colitis and lymphoma either co-existed in this patient (with diagnosis of lymphoma being missed initially) or the lymphoma occurred later in the background of ulcerative colitis. This patient fulfils Dawson’s criteria for primary gastrointestinal lymphomas, i.e. absence of superficial lymphadenopathy at presentation, no obvious enlargement of mediastinal lymph nodes, normal peripheral smear, and no involvement of the spleen and liver except contiguous involvement.[15] Even though MALT lymphoma is believed to have an indolent course, majority of cases of rectal MALT lymphoma reported so far have been treated with surgery, chemotherapy or a combination of both.[9] Spontaneous regression of rectal MALT lymphoma after antibiotic treatment has been noted in the presence as well as absence of Helicobacter pylori infection in patients without underlying inflammatory bowel disease. Local endoscopic therapy with or without treatment for H. pylori has been proposed to be a reasonable treatment by some authors.[8] However, management with antibiotics alone (targeted at H. pylori) has given variable results. Some authors have found antibiotic treatment to be ineffective in patients with extragastric MALT lymphoma even if an H. pylori infection was confirmed.[16] Complete remission with the use of radiation therapy in addition to chemotherapy has also been reported.[9,17]

Such non-operative treatment approaches may however, not be applicable to patients with ulcerative colitis. Disease recurrence would be difficult to differentiate from a relapse of ulcerative colitis. Detection of residual or recurrent disease by endoscopy would be difficult in the background of inflammation in the colon or rectum. Many of these patients are on immunosuppressive therapy and may not have an indolent course. In addition, many of these patients need surgery because of refractory disease or complications of medical treatment as in our patient.

Given its rarity, there is lack of information regarding the appropriate management of rectal MALT lymphoma in the setting of ulcerative colitis. We could not find any report on management of patients found to have incidentally detected MALT lymphoma in the resected specimen. As our patient was young, we offered her chemotherapy. Since there was no residual disease, no further surgery was warranted.

Rectal MALT lymphoma is rare in patients with ulcerative colitis. The endoscopic picture may be difficult to differentiate from changes due to ulcerative colitis. There is lack of evidence to support one modality of treatment over the other. Overall good outcome can be achieved with the use of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients detected to have unsuspected MALT lymphoma in the resected bowel.

References

- Wong MT, Eu KW. Primary colorectal lymphomas. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8:586–91.

- Farrell RJ, Ang Y, Kileen P, O’Briain DS, Kelleher D, Keeling PW, et al. Increased incidence of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in inflammatory bowel disease patients on immunosuppressive therapy but overall risk is low. Gut. 2000;47:514–9.

- Beaugerie L, Brousse N, Bouvier AM, Colombel JF, Lémann M, Cosnes J, et al. Lymphoproliferative disorders in patients receiving thiopurines for inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective observational cohort study. Lancet. 2009;374:1617–25.

- Korelitz BI, Mirsky FJ, Fleisher MR, Warman JI, Wisch N, Gleim GW. Malignant neoplasms subsequent to treatment of inflammatory bowel disease with 6-mercaptopurine. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3248–53.

- Tan CW, Wilson GE, Howat JM, Shreeve DR. Rectal lymphoma in ulcerative colitis treated with azathioprine. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:989–92.

- Shibahara T, Miyazaki K, Sato D, Matsui H, Yanaka A, Nakahara A, et al. Rectal malignant lymphoma complicating ulcerative colitis treated with long-term cyclosporine A. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:336–8.

- Shepherd NA, Hall PA, Coates PJ, Levison DA. Primary malignant lymphoma of the colon and rectum. A histopathological and immunohistochemical analysis of 45 cases with clinicopathological correlations. Histopathology. 1988;12:235–52.

- Ahlawat S, Haddad N, Kanber Y, Cohen P, Ozdemirli M, Benjamin S. Primary mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma occurring in the rectum. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:443–4; discussion 4.

- Foo M, Chao MW, Gibbs P, Guiney M, Jacobs R. Successful treatment of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma of the rectum with radiation therapy: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1719–23.

- Tsutsuml Y, Nakamura M, Machimura T. CD30-positive T cell lymphoma of the intestine, complicating ulcerative colitis. Pathol Int. 1996;46:384–8.

- Godoy P, Calderaro DC. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the colon and ulcerative colitis. Case report. Arq Gastroenterol. 1999;36:85–9.

- Kakimoto K, Inoue T, Nishikawa T, Ishida K, Kawakami K, Kuramoto T, et al. Primary CD56+ NK/T-cell lymphoma of the rectum accompanied with refractory ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:576–80.

- Loehr WJ, Mujahed Z, Zahn FD, Gray GF, Thorbjarnarson B. Primary lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract: a review of 100 cases. Ann Surg. 1969;170:232–8.

- Friedman HB, Silver GM, Brown CH. Lymphoma of the colon simulating ulcerative colitis. Report of four cases. Am J Dig Dis. 1968;13:910–7.

- Dawson IM, Cornes JS, Morson BC. Primary malignant lymphoid tumours of the intestinal tract. Report of 37 cases with a study of factors influencing prognosis. Br J Surg. 1961;49:80–9.

- Grünberger B, Wöhrer S, Streubel B, Formanek M, Petkov V, Puespoek A, et al. Antibiotic treatment is not effective in patients infected with Helicobacter pylori suffering from extragastric MALT lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1370–5.

- Guney N, Basaran M, Aksakalli N, Bavbek S, Erseven G. Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the rectum. Onkologie. 2007;30:385–7.

|

|

|

|

|

|