Introduction

Whipple’s pancreatico-duodenectomy (WPD) remains the only potentially curative treatment for periampullary tumours, including carcinoma head of pancreas (HOP) and distal cholangiocarcinoma. The first laparoscopic WPD was reported by Gagner and Pomp in 1994.1 Following technical improvements and accumulation of laparoscopic skills, WPD is being widely performed laparoscopically. The inherent technical difficulty of resection and intracorporeal reconstruction makes laparoscopic WPD the most technically demanding advanced surgical procedure with slow adoptability. Various studies, including meta-analysis, have shown the safety and feasibility of laparoscopic WPD with the advantages of minimally invasive approach like reduced blood loss, surgical site infection (SSI), and decreased hospital stay compared to open WPD.2,3 Previously, we have reported the feasibility and safety of pancreatogastrostomy (PG) technique using “modified Double U Stich”in laparoscopic WPD.4 In this report, we compared the short-term outcomes of laparoscopic WPD to open WPD for resectable periampullary tumours including carcinoma HOP and distal cholangio carcinoma.

Methods

Design

A retrospective analysis of a prospectively maintained database of patients who underwent WPD in a single surgical unit in the department of surgical gastroenterology of Govind Ballabh Pant Institute of Post-Graduate Medical Education and Research, a tertiary care institute situated in Delhi, India.

Study Population

One hundred thirteen patients who underwent WPD between November 2017 to May 2021 at our institute were reviewed. Adult patients with resectable periampullary tumours, including pancreatic head neoplasms and distal cholangio carcinoma, were included. The primary approach planned for WPD was the laparoscopic method and open approach was considered when there were concerns in the early part of COVID pandemic, vascular involvement on preoperative imaging, and general contraindications to advanced laparoscopy. Patients in whom the procedure was converted to open were excluded from the study. The same surgical team performed all the procedures.

Preoperative work up included routine hematological and biochemical investigations, tumour marker (CA 19-9), and triphasic contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of abdomen for preoperative staging. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) was done in selected cases. Preoperative biliary drainage was done in patients with serum bilirubin levels exceeding 15 mg/dL, evidence of cholangitis, poor nutritional status, or renal insufficiency.

Patient’s data collected included demographics and preoperative details (age, sex, CA19-9 levels, jaundice, preoperative stenting), intraoperative parameters (operating time, blood loss), postoperative length of hospital stay, median ICU stay, time to resume oral diet, postoperative complications, interventional procedures and mortality. The severity of complications was scored using the Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications5. The amylase level in the surgical drains was measured on postoperative day (POD) 1, POD 3, and POD 5. Postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF)6, delayed gastric emptying (DGE)7, and postpancreatectomy haemorrhage (PPH)8 were scored and graded according to standard international consensus definitions. Reoperation and readmission were defined as any unplanned operation or admission within 90 days of the primary procedure related to pancreatic resection. Final histopathology, margin status, and lymph node involvement were recorded as well. Patients were followed up at 2 weeks, 4 weeks, 3 months, biannually for 2 years and yearly thereafter and evaluated with liver function tests, tumour markers, ultra-sonogram abdomen, and CECT abdomen.

Operative Technique

Laparoscopic WPD

Patient was placed in reverse Trendelenburg supine position with legs apart. Pneumoperitoneum was created via trocar inserted infra-umbilically in the midline by open technique. Six ports placement was done as previously described by the surgical team.4 Staging laparoscopy was done in all the patients to rule out metastatic disease. Lesser sac was entered by division of gastrocolic omentum. Kocher manoeuvre was performed upto the left of IVC. Following division of gastrocolic loop of Henle, portal vein was identified at the inferior border of pancreas and a tunnel was created between pancreatic neck and SMV/portal vein. Gastroduodenal artery (GDA) was isolated at the upper border of pancreas and divided after test clamping. Neck of pancreas was divided with harmonic scalpel/stapler, and uncinate dissection was completed. Standard lymphadenectomy included removal of pancreaticoduodenal, pericholedochal, periportal, along hepatic artery lymph nodes and lymph nodes to the right of coeliac and superior mesenteric artery.

Common bile duct (CBD) was dissected and transected. Stomach was transected proximal to pylorus using Echelon flex endopath® 60 mm blue or green cartridge. Resection was completed after transecting jejunum 10 cms distal to duodenojejunal flexure or duodenal transection to the right of the SMV.

Pancreato-enteric reconstruction was done using pancreato-gastrostomy (PG) by “modified Double U Stitch” technique.4 Pancreatic stump was mobilised for a length of 3-4 cms. Anterior longitudinal gastrotomy and posterior horizontal/oblique gastrotomy incision were made. Pancreatic stump was pulled into the stomach for a length of 2-3 cms. PG was done by dunking technique using two ‘U’ shaped prolene 2/0 sutures to the posterior wall of stomach passing across the pancreas, suturing was done through the wide anterior gastrostomy.

Hepaticojejunostomy (HJ) was completed by performing an end-to-side, retrocolic HJ using 3/0 or 4/0 PDS sutures. Anterior gastrotomy was used for gastrojejunostomy (GJ) and antecolic GJ was done at 40 cm distal to HJ by using 3/0 PDS sutures. Feeding jejunostomy was done in all the patients. Specimen was retrieved via the infra-umbilical port after extending the incision or via Pfannenstiel incision.

Open WPD

Staging laparoscopy was done in all patients. In the absence of metastasis, bilateral subcostal incision was used. Resection and method of reconstruction were similar to laparoscopic WPD. One drain was placed in subhepatic region and other in the lesser sac. The drain was removed when the output was less than 50 ml with nature of output being serous in nature.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were expressed as percentages and continuous variables as median. Categorical variables were compared with the Chi-square test. Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare continuous variables. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

In the study period, 113 patients underwent WPD with curative intent which included open WPD (n=41) and laparoscopic WPD (n=67) patients. Conversion from laparoscopy to open was required in 5 patients (7%). Reasons for conversion were significant venous involvement requiring vein resection (n=2), intraabdominal adhesion and due to previous surgery (n=1) or intraoperative bleeding (n=2).

Table 1 shows the demographic data and preoperative details. Median age was similar in both the groups. More patients in laparoscopic group were female as compared to open group in which male sex predominated. 76.1% of the patients in laparoscopic group underwent preoperative biliary drainage while 82.9 % of patients in open group underwent biliary drainage. Most common indication for WPD was ampullary tumours in both the groups.

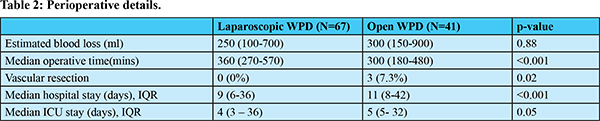

Estimated blood loss was comparable between both groups (median 250 vs 300 mL, p=0.88). Three patients (7.3 %) in the open WPD group underwent venous resection (sleeve resection in 2 patients and resection with end-to-end anastomosis in 1 patient). Laparoscopic WPD was associated with longer operative time (median 360 vs 300 min, p<0.001). Duration of hospital stay was significantly shorter in laparoscopic group as compared to open group (median 9 vs 11 days, p<0.001) with decreased ICU stay. Perioperative details are summarized in table 2.

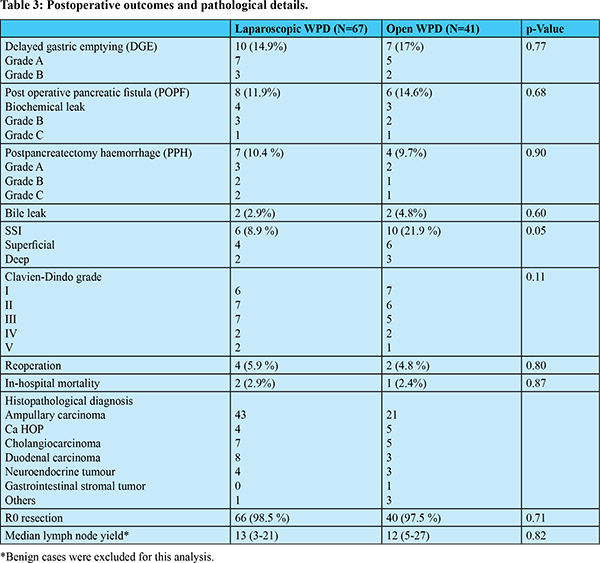

Table 3 summarizes the postoperative outcomes and pathological details for both groups. Postoperative complications were comparable between two groups except surgical site infection (SSI) which was significantly lower in laparoscopic group (8.9 vs 21.9 %, p = 0.05). Reoperation rates were comparable in both the groups (5.9vs 4.8 %, p =0.80). The usual indication for reexploration was Grade B or Grade C PPH. In-hospital mortality rates (2.9 vs 2.4%, p=0.87) were similar for both laparoscopic WPD and open WPD. Clavien-Dindo grade III or higher complications occurred in 11 (16.4%) patients after laparoscopic WPD and 8 (19.5%) patients after open WPD. The difference was not statistically significant (p=0.68). 1 patient in each group died secondary to septicemia with multiorgan dysfunction. One patient in laparoscopic WPD group died secondary to acute myocardial infarction in postoperative period. Median lymph node yield and number of R0 resections were similar between the two groups.

Discussion

Minimally invasive surgery (MIS) has replaced open technique in a wide range of surgical procedures. WPD is the only potential cure for periampullary malignancies. Pancreas specific complications are the leading causes of morbidity and mortality following WPD. Although the benefits of MIS are established, pancreas specific complications are not specifically targeted by these improved techniques. Inherent complexity of intracorporeal reconstruction and lack of large volume data has limited the use of laparoscopy in WPD to selected centres engaged in advanced laparoscopic hepatobiliary surgery.9,10 Increased experience in pancreatic surgery coupled with advancements in surgical techniques have reduced the postoperative morbidity and mortality following WPD. Laparoscopic WPD has been increasingly performed at our institution with the intent to improve short term postoperative outcomes while maintaining the oncological adequacy.

Pancreatico-enteric anastomosis is the Achilles’ heel of WPD and is the significant cause of postoperative morbidity. Pancreatojejunostomy (PJ) was the choice of reconstruction at our institution before 2017. Since November 2017, we began PG using “modified Double U Stitch” technique for both laparoscopic and open WPD.4 Potential physiological advantages of PG: (a) PG is relatively simpler and even suitable for small diameter ducts and outcome does not depend on the texture of gland and size of duct, (b) deactivation of pancreatic enzymes by the acidic pH in stomach hence decreasing autodigestion by pancreatic enzymes, (c) less tension on the pancreatic anastomosis because of close proximity between the posterior gastric wall and the pancreatic remnant.11

Various review articles and metanalyses have compared the results of laparoscopy and open WPD.12-14 Till date, 5 randomized control trials (RCTs) comparing the short-term outcomes of laparoscopic WPD versus open WPD have been published.15-19 Recently ametanalys is of 4 RCTs by Bhavin V et al. showed significantly lower blood loss and SSI in laparoscopy group without any significant difference in hospital stay, postoperative morbidity, and 90 days mortality.14

In our study, majority of the patients had ampullary tumour in both open and laparoscopic group which was similar to PLOT trial. However, PADULAP and LEOPARD2 trials had pancreatic head malignancy type as the majority (46.9% and 28% respectively).16,17

In our study the median operative time was 360 mins and 300 mins in laparoscopic and open group respectively (p<0.001), which were shorter than 486 mins vs. 365 mins in PADULAP trial and and 410 mins vs 274 mins in LEOPARD 2 trial, and comparable to 359 mins vs. 320 mins in PLOT trial.15,16,17 The reduced operative time in our study could be because of predominance of ampullary tumours and PG anastomotic reconstruction which could be fashioned in a shorter time. Some of the previous trial shave shown decreased blood loss in laparoscopic group compared to open group.15,16 In our study, blood loss between laparoscopic and open group was not statistically significant (250 vs 300 ml, p =0.88).

Three (7.3%) patients in open group underwent vascular resection in terms of portal vein resection (2 patients) and IVC sleeve resection (1 patient) while none of the patients in laparoscopic group underwent vascular resection. Patients with suspicious involvement of vessels on preoperative imaging were directly planned for open WPD or were assessed for venous involvement laparoscopically. Procedure was converted to open (7%) when vascular resection was mandated. Need for a vascular resection is one of the indication for conversion in this study. However, some studies have reported a high percentage of vascular resections (17-20%) during laparoscopic procedures.20

Overall POPF as well as clinically significant POPF rates were comparable between both the groups. Other complications like bile leak and DGE were comparable between laparoscopic and open WPD and were also similar to published results.15-17 Overall morbidity (Clavien-Dindo classification) as well as mortality was not found to be statistically significant between the two groups (p=0.11, p=0.87). Main causes of mortality were septicaemia with multiorgan dysfunction secondary to PPH, POPF and acute myocardial infarction in 1 patient. These results were in tune with the results of PLOT and PADULAP trials.15,16 But the LEOPARD 2 trial showed higher incidence of complication-related mortality in laparoscopic group (10 vs 2%) which led to premature termination of the trial.17 The reasons attributed to higher mortality in LEOPARD-2 trial are multicentric nature and WPD being performed by less experienced surgeons (23-34 laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomies performed by the centres).

PPH is the most urgent and potentially life-threatening complication of WPD with a high mortality rate. Overall PPH rates were comparable between two groups (10.4 vs 9.7%, p=0.90). 5.9% and 4.8% of the patients experienced clinically significant PPH (grade B and C) in laparoscopy and open group, respectively. The incidence of PPH was higher in initial study period and source of bleed was from the pancreatic transection surface. In the later part of our experience, incidence of PPH decreased with the use of vascular staplers or mattress sutures taken through pancreatic surface.

In our study, median length of hospital stay was 9 days in laparoscopic group and 11 days in open group (p<0.001). In the PLOT trial, median hospital stays for patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery was 7 days vs 13 days in open surgery (p=0.001).15 Other trials also showed significant difference in hospital stay.16,18 Reasons for decreased hospital stay in laparoscopic procedures were early post- operative recovery, less pain, and less incidence of SSI (8.9 vs 21.9 %, p=0.05). An advantage of laparoscopic group is early postoperative recovery which helps in reducing the interval to initiate adjuvant chemotherapy.

R0 resection is one of the most important prognostic factors following WPD. In the current study, R0 resection could be achieved in 98.5% and 97.5% of the patients in laparoscopic and open group, respectively. Lymph node yield is considered one of the prognostic factors for staging. In our study, the median lymph node yield was 13 in laparoscopic group and 12 in open group which was not statistically significant (p=0.82) and is in accordance with the published literature.15-17

Laparoscopic WPD being a technically challenging procedure and having a steep learning curve are the reasons for its low adoption. The main challenges include the resection part and the pancreaticoenteric anastomosis. For making the adoption of laparoscopic WPD quicker. A phase wise approach can be employed. We have adopted this approach over the years, progressing from our earlier laproscopy-assisted approach to this current experience of entirely laparoscopic approach. In the initial part of adoption it is more pruder to start with small periampullary tumors where resection is easier compared to pancreatic head tumors. As in the early part of our experience after resection, a lap-assisted approach can be used where in hepaticojejunostomy can be completed laparoscopically and the pancreaticoenteric anastomosis and gastrojejunostomy can be fashioned from a small midline wound through which the specimen is retrieved.

We routinely perform PG anastomosis which has noninferior outcomes to pancreatojejunostomy reconstruction method. PG reconstruction takes a shorter time for reconstruction, less steep learning curve and reproducibility and is easier to teach the trainee surgeons. Such a phase wise manner of approaching laparoscopic WPD procedure may be helpful in increased adoptability without compromising on patient safety.

Conclusion

In conclusion, laparoscopic WPD appears to be safe and feasible with added advantages of minimally invasive surgery. With similar short-term outcomes and non-inferior early oncological outcomes compared with that of open WPD. Further long-term results (survival) are needed to validate the oncological adequacy.

References

- M. Gagner, A. Pomp. Laparoscopic pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy, Surg. Endosc. 1994;8:408–10.

- Palanivelu C, Jani K, Senthilnathan P, Parthasarathi R, Rajapandian S, Madhankumar MV. Laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy: technique and outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2007; 205:222–30.

- Qin R, Kendrick ML, Wolfgang CL et al. International expert consensus on laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2020 Aug;9(4):464-83.

- Javed A, Kumar N CH, Kiran S, et al. “Pancreatic Reconstruction With Modified Technique Using A ‘Double U Stitch Pancreatogastrostomy’ Following A Laparoscopic Whipple’s Pancreaticoduodenectomy.” Trop Gastro. 2022 Oct-Dec (vol 42. 4).

- Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004 Aug;240(2):205-13.

- Bassi C, Marchegiani G, Dervenis C, et al. The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 Years After Surgery. 2017;161(3):584-91.

- Wente MN, Bassi C, Dervenis C, et al. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after pancreatic surgery: a suggested definition by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery. 2007;142(5):761-8.

- Grützmann R, Rückert F, Hippe-Davies N, Distler M, Saeger HD. Evaluation of the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery definition of post-pancreatectomy hemorrhage in a high-volume center. Surgery. 2012;151(4):612-20.

- Asbun HJ, Stauffer JA. Laparoscopic vs open pancreaticoduodenectomy: overall outcomes and severity of complications using the accordion severity grading system. J Am Coll Surg. 2012; 215:810–9.

- Correa-Gallego C, Dinkelspiel HE, Sulimanoff I, Fisher S, Vinuela EF, Kingham TP, Fong Y, DeMatteo RP, D’Angelica MI, Jarnagin WR. Minimally invasive vs open pancreaticoduodenectomy: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Surg. 2014; 218:129–39.

- Osman MM, Abd El Maksoud W. Evaluation of a new modification of pancreaticogastrostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy: anastomosis of the pancreatic duct to the gastric mucosa with invagination of the pancreatic remnant end into the posterior gastric wall for patients with cancer head of pancreas and periampullary carcinoma in terms of postoperative pancreatic fistula formation. Int J Surg Oncol. 2014; 2014:490386.

- Aiolfi A, Lombardo F, Bonitta G et al. Systematic review and updated network meta-analysis comparing open, laparoscopic, and robotic pancreaticoduodenectomy. Updates Surg. 2021. 73: 909–22.

- Vasavada B, Patel H. Laparoscopic vs Open Pancreaticoduodenectomy- An Updated Metaanalysis of Randomized Control Trials. 2021. Preprints, 2021050295.

- Nickel F, Haney CM, Kowalewski KF et al. Laparoscopic Versus Open Pancreaticoduodenectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Annals of Surgery. 2020 Jan;271(1):54-66.

- Palanivelu C, Senthilnathan P, Sabnis SC, Babu NS, Srivatsan Gurumurthy S, Anand Vijai N, Nalankilli VP, Praveen Raj P, Parthasarathy R, Rajapandian S. Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic versus open pancreatoduodenectomy for periampullary tumours. Br J Surg. 2017 Oct;104(11):1443-50.

- Poves I, Burdío F, Morató O, Iglesias M, Radosevic A, Ilzarbe L, Visa L, Grande L. Comparison of Perioperative Outcomes Between Laparoscopic and Open Approach for Pancreatoduodenectomy: The PADULAP Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Surg. 2018 Nov;268(5):731-9.

- van Hilst J, de Rooij T, Bosscha K, Brinkman DJ, van Dieren S, Dijkgraaf MG, Gerhards MF, de Hingh IH, Karsten TM, Lips DJ, et al. Laparoscopic versus open pancreatoduodenectomy for pancreatic or periampullary tumours (LEOPARD-2): a multicentre, patient-blinded, randomised controlled phase 2/3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019; 4:199–207.

- Bhingare P, Wankhade S, Gupta BB, Dakhore S. A prospective randomized controlled trial comparing laparoscopic versus open Whipple’s procedure for periampullary malignancy. Int Surg J. 2019; 6:679-85.

- Wang M, Li D, Chen R, Huang X et al. Laparoscopic versus open pancreatoduodenectomy for pancreatic or periampullary tumours: a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Jun;6(6):438-47.

- Croome KP, Farnell MB, Que FG, Reid-Lombardo KM, Truty MJ, Nagorney DM et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with major vascular resection: a comparison of laparoscopic versus open approaches. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015; 19:189–94.