48uep6bbphidcol2|ID

48uep6bbphidvals|2951

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Introduction

Cirrhosis is the end-stage manifestation of liver injury that leads to necroinflammation and fibrosis of the liver. The major complications of cirrhosis include variceal bleed, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy (HE), hepato-pulmonary hypertension, acute kidney injury (AKI) including hepato-renal syndrome, coagulation disorders, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Ascites is the most common complication that leads to hospital admission and is associated with substantially increased mortality.1,2 Roughly 15% of the patients with ascites will die within one year, and 44% within five years.3

Infections are a frequent, recurrent complication of cirrhosis that leads to multiple hospital visits and admissions. Worldwide prevalence of bacterial infection in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis ranges between 33%-47%, and is responsible for 30-50% of deaths in cirrhosis.4 Additionally, infections itself may precipitate complications like HE or AKI, which may become detrimental in a slowly progressive compensated liver disease. Common infections in these patients include spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) (25%), urinary tract infection (20%), pneumonia (15%), cellulitis, and spontaneous bacteremia.5 Among these, SBP is the most common and life-threatening infection, with prevalence ranging from 10% to 30% in hospitalized patients and 1.5% to 3.5% in patients who are not hospitalized.6,7 The one-year probability of development of the first SBP in cirrhotic patients with ascites is approximately 10%. The occurrence of an episode of SBP reduces the survival rate at one year to 30% and 20% at two years.8 The term “critically ill cirrhotic” is rightly applied to cirrhotic patients following infections like SBP.9

The diagnosis should be considered in any patient with cirrhosis, ascites, and clinical deterioration. Unlike GI bleed or HE, SBP has a less dramatic presentation, which causes a delay in seeking medical care. Rarely, it may be clinically silent without apparent signs or symptoms. Some studies suggest that the clinical usefulness of paracentesis is less important in the out-patient setting as the diagnostic yield for SBP or its variants is less than 4%.10,11 However, risk factor identi?cation and symptom-based selection of patients for diagnostic paracentesis are detrimental, since symptoms are often non-specific and deterioration of liver disease is the outcome without treatment. Despite paracentesis being vital for diagnosis, it is under-utilized being performed in only 60% of hospitalized cirrhotics with ascites.11 In patients who do undergo paracentesis, delay in procuring ascitic ?uid for analysis has shown a 2.7-fold increased risk of in-hospital mortality.12 The effect of delay in the administration of antibiotics on outcomes is well studied in many infections,13 but its relevance is rarely addressed in SBP.

In developing countries, patients and caregivers to cirrhotic patients often neglect minor changes in daily symptoms. This delay may be secondary to multiple social and economic reasons. However, it is crucial to address these issues and consider proper counseling about the need for a prompt visit to a doctor with any new onset of symptoms and or deterioration of the liver disease. This study aimed to determine factors associated with a delay in the diagnosis and treatment of SBP and its impact on the outcome.

Materials and Methods

The study was a prospective cohort study conducted in a tertiary care center of northern Kerala over a period of 12 months from February 2015 to February 2016. All cirrhotic patients admitted with a diagnosis of SBP (first episode/ recurrent) were included. Cirrhotic patients with ascites with new onset symptoms of fever, abdominal pain, loose stools, decreased urine output, or altered sensorium underwent an abdominal paracentesis. SBP was diagnosed as per standard criteria of absolute neutrophil count more than 250 cells/µL in ascitic fluid. Patients with secondary peritonitis, ascites due to tuberculosis and malignancy were excluded. Patients and caregivers were interviewed with a pre-set questionnaire. Details obtained included duration between onset of symptoms and the first healthcare visit, which was considered the first admission to any hospital, a clinic or the emergency department of our hospital. Subsequently, patients were followed up, and the time duration from the first hospital approach to our department was arbitrarily defined as the time-gap between the hospital approach to treatment. This time-gap includes time interval for abdominal paracentesis, ascitic fluid analysis, and treatment. In those with confirmed spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, the onset of symptoms or deterioration in general conditions was considered the onset of SBP.

All patients received intravenous cefotaxime initially. Paracentesis was repeated after 48 hours, and if there was an absence of at least a 25% reduction in absolute neutrophil count, the antibiotic was changed to piperacillin-tazobactam or as per culture report if available. During the hospital stay, patients were monitored for other complications like hepatic encephalopathy, sepsis, kidney injury, and death. Also, caregivers/patients were requested to respond to a questionnaire to assess the socio-cultural factors for any delay in seeking medical assistance. Informed written consent was obtained from each patient or caregiver. The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee and research committee.

Statistical Methods

Qualitative data were presented as proportion, and the continuous data were presented as median (range). Categorical variables were analyzed using Chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test as applicable. Data were analyzed by SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

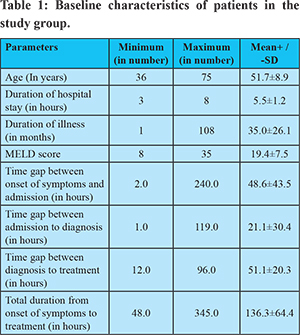

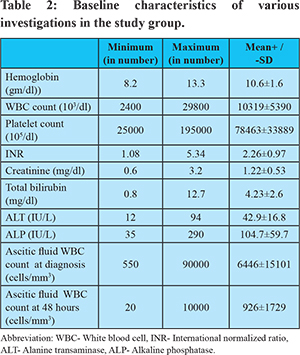

There were a total of 41 patients with SBP, with 38 males(92%) and mean (±SD) age 51±8 years. The most common etiology for cirrhosis was alcohol (n=24,58%) followed by non alcoholic fatty liver disease(NAFLD, n=5, 12%), cryptogeniccirrhosis (n=5, 12%), hepatitis B (n=4, 9.7%) and hepatitis C (n=3, 7.3%). The mean duration of cirrhosis was 35±26 months before the onset of SBP. The mean time-gap between symptom onset and visit to the hospital was 48.6±43.5 hours, between the first hospital visit and the initiation of treatment was 51.1±20.3 hours. The mean duration of hospital stay was 5.5±1.2 days. The total duration between the onset of symptoms to treatment was 136.3±64.4 hours. The majority of patients belonged to Child Turcott Pugh (CTP) class C (n=32, 78%), followed by 9 patients (22%) with CTP B status. The mean MELD score was 19.46±7.5. Relevant timeline parameters are shown in table 1, and investigations in table 2.

Fever was the most common symptom among these patients (80.4%), followed by an increase in abdominal distension (75.6%), and pain abdomen (48.7%). Fifteen patients (36.6%) presented to the hospital because of new-onset hepatic encephalopathy in the form of decreased consciousness and altered sensorium. Other reported symptoms included loose stools, decreased urine output, and upper GI bleed. Fifteen patients (36.6%) with a prior history of SBP were on secondary prophylaxis with Norfloxacin. Antibiotics were changed after 48 hours in 13 patients (31.7%) due to inadequate response, as defined above. Only ten (9.7%) patients had growth in the ascitic fluid culture. E. coli was the most common organism, followed by klebsiella. Among 41 patients, 18 patients (44%) developed complications in the form of acute kidney injury(n=7, 17%), hypotension(n=2, 4%), sepsis(n=8, 19.5%) or hepatic encephalopathy(n=15, 37%). Eleven patients died during the admission period, compounding to a mortality rate of 26.5%.

The time-gap between symptom onset and treatment was considerably higher among patients with complications compared to patients without complications (104 vs. 68 hours, p=0.03). The reasons for a delay in admission to hospitals were unawareness about this complication(61%), family problems (49%), indifference to symptoms (12%), and financial problems(8%).

Factors Affecting Mortality in SBP Patients

Univariate analysis showed that factors significantly associated with mortality (Table 3 and 4) were age (p value= 0.04), non response to first antibiotic within first 48 hours(p value = 0.001), occurence of complications including hepatic encephalopathy(p value = 0.001), hypotension(p value=0.017), sepsis(p value = 0.002), time-gap between symptom onset and hospital visit(p value=0.001), and subsequently to treatment (p value=0.005).

Discussion

This is the first Indian study to determine factors for delay in the diagnosis of SBP and its impact on the outcome of SBP. This study showed that awareness in the community about this complication is low (61%) despite recurrent admissions to hospital (36.6% were already on prophylaxis for SBP). Older age, inadequate response to an initial antibiotic, the occurrence of complications like HE, hypotension, and sepsis were significantly associated with mortality. The time gap between the onset of symptoms to treatment determines the outcome in these patients on univariate analysis. However, the multivariate analysis failed to show an association between time-gaps studied and mortality. This could be due to the duration of illness, severity (most patients in CTP class C), and various associated complications with cirrhosis and SBP like HE, sepsis, and AKI, which eventually determines outcomes in these patients.

The present study showed that there is a delay in seeking admission to the hospital, which can lead to complications, including death. In our study, the mean time-gap between symptom onset to treatment was 136.3+/-64.4 hours. Kim et al. demonstrated that each hour of delay in paracentesis was associated with a 3.3% increase in mortality, after adjusting for MELD score and creatinine levels.12 Patients who underwent delayed paracentesis (12-72 hours) compared to early paracentesis(<12 hours) group demonstrated higher in-hospital mortality (27% vs. 13%, P=0.007), 3-month mortality and duration of hospital stay.12 In a study by Orman et al. in-hospital mortality was 5.7% for those whose paracentesis was performed one day after admission, compared to 8.1% when paracentesis was delayed (p = 0.049).11

As in other cohorts, most patients with SBP in our study belong to advanced cirrhosis with high CTP and MELD scores. The mean MELD score was comparable to previous studies with SBP, where the score ranges from 16 to 22.15,16 Alcohol and cryptogenic cirrhosis form the major etiology for cirrhosis in India.17,18 The most common etiology in our study was alcohol, followed by NAFLD, cryptogenic, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C.

The symptoms of SBP in our study of fever, abdominal distension, and pain abdomen were as reported in the literature.19 Also, 9.8% of patients had upper GI bleed before the onset of SBP, which is a well-known risk factor for SBP, requiring primary prophylaxis.20

In more recent studies, the mortality rate related to this complication was around 20%-30%.21 However, after an initial diagnosis of SBP, the 1-month, 6-month and 1-year mortality rates are 33%, 50%, and 58%, respectively. Major prognostic factors of cirrhotics with SBP include CTP score, MELD, increased serum levels of bilirubin and creatinine. Bacteremia and lack of therapeutic response are significant independent risk factors of mortality associated with SBP. Also, recent history of variceal bleeding, the severity of infection, and the degree of hepatic and renal impairment influence short-term prognosis of patients with SBP.22

The index of suspicion for SBP should be high, and the threshold to consider diagnostic paracentesis should be low to diagnose every case at the earliest. This is hindered by the fact that hospitals may avoid admission in these chronic immunocompromised cases for fear of nosocomial infections. The nationwide inpatient sample(NIS) study found that only 61% of patients with cirrhosis admitted for ascites or encephalopathy underwent paracentesis. When performed, only two-thirds had paracentesis within the first day of admission.11 These characteristics may be worse in primary health centers, which is the first hospital contact for most patients in developing countries. The time-gap between a hospital visit to treatment was 51 hours, signifying hurdles every patient passes through from a primary health center to reach the specialty department. Although delay to diagnosis and treatment in most government hospitals is inevitable, it is essential to educate the society about the need for early diagnosis and referral in cirrhosis patients. Our study sheds light on this vital aspect that outcome in SBP is related to socio-economic and technical factors associated with the diagnosis.Being a community gastroenterologist, our prime aim is not only to treat the disease and monitor for complications, but to provide adequate preventive measures to these patients. The most common reason for the delay in hospital visit was unawareness about the complications present in 61% of patients. Besides delay in seeking admission, there was a mean delay of 15 hours for beginning treatment after hospitalization. This may be due to the delay in performing diagnostic paracentesisor getting results from the laboratory, which is common, especially in a high throughput packed government hospitals such as ours.

The most analogous issue in this study is the method of assessment of the time gap between symptom onset and its diagnosis and treatment. There is a subjective element in that the symptom of clinical deterioration need not coincide with the starting of the infection. However, in the absence of another objective method, we had to arbitrarily take the time gap as the gap between the onset of new symptom or deterioration of liver disease necessitating the hospital admission and the diagnosis of SBP after hospital admission. A similar approach is used for the diagnosis of acute liver failure, where jaundice detection is taken as the time of onset of disease.23

Conclusion

Infections in cirrhosis, like other immunocompromised states, is detrimental to disease outcome. Early identification and treatment improve short term complications and long term prognosis, which otherwise has a natural downward course over time. The duration of symptom onset to approach to a hospital and treatment of SBP were significantly higher in patients who died due to SBP. The main cause of this delay is unawareness among patients and relatives about this masked complication. Hence, prompt education about this complication at the time of the initial diagnosis of cirrhosis is critical.

Abbreviations:

AKI- Acute kidney injury

ALP- Alkaline phosphatase

ALT- Alanine transaminases

CTP- Child Turcotte Pugh

HCC- Hepatocellular carcinoma

HE- Hepatic encephalopathy

MELD- Model for end-stage liver disease

NAFLD-Non alcoholic fatty liver disease

NIS- Nationwide inpatient sample

SBP- Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

References

- Ginés P, Quintero E, Arroyo V, Terés J, Bruguera M, Rimola A, et al. Compensated cirrhosis: natural history and prognostic factors. Hepatology 1987; 7: 122-128.

- Lucena MI, Andrade RJ, Tognoni G, Hidalgo R, De La Cuesta FS. Multicenter hospital study on prescribing patterns for prophylaxis and treatment of complications of cirrhosis. Eur J ClinPharmacol 2002; 58: 435-440.

- Ruiz-del-Arbol L, Monescillo A, Arocena C, Valer P, Ginès P, Moreira V, et al. Circulatory function and hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. Hepatology 2005; 42: 439–447.

- Caly WR, Strauss E. A prospective study of bacterial infections in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol 1993; 18: 353-358.

- Navasa M, Fernández J, Rodés J. Bacterial infections in liver cirrhosis. Ital J GastroenterolHepatol 1999; 31: 616-625.

- Rimola A, Garcia-Tsao G, Navasa M, et al. Diagnosis, treatment and prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: a consensus document. International Ascites Club. J Hepatol. 2000; 32:142–53.

- Evans LT, Kim WR, Poterucha JJ, Kamath PS. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in asymptomatic out-patients with cirrhotic ascites. Hepatology. 2003;37(4):897-901

- Danulescu RM, Stanciu C, Trifan A. Evaluation of prognostic factors in decompensated liver cirrhoisis with ascites and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Rev Med Chir Soc Med Nat Iasi. 2015 ;119(4):1018-24.

- Arvaniti V, D’Amico G, Fede G, et al. Infections in patients with cirrhosis increase mortality four-fold and should be used in determining prognosis. Gastroenterology 2010;139:1246-1256.

- Evans LT, Kim WR, Poterucha JJ, et al. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in asymptomatic out-patients with cirrhotic ascites. Hepatology 2003; 37: 897–901.

- Orman ES, Hayashi PH, Bataller R, et al. paracentesis is associated with reduced mortality in patients hospitalized with cirrhosis and ascites. Clin GastroenterolHepatol 2014; 12: 496–503.

- Kim JJ, Tsukamoto MM, Mathur AK, et al. Delayed paracentesis is associated with increased in-hospital mortality in patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2014; 109: 1436–42.

- Kumar A, Roberts D, Wood K et al. duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock. Crit Care Med 2006; 34: 1589–95.

- Heidelbaugh JJ, Bruderly M. Cirrhosis and chronic liver failure: part I. Diagnosis and evaluation. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(5):756-62.

- Coral G, Mattos AA, Damo DF, Viégas AC. Prevalence and prognosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Experience in patients from a general hospital in Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil (1991-2000). ArqGastroenterol. 2002; 39(3):158-62.

- Kraja B, Sina M, Mone I, et al. Predictive Value of the Model of End-Stage Liver Disease in Cirrhotic Patients with and without Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:539059.

- Ray G, Ghoshal UC, Banerjee PK, Pal BB, Dhar K, Pal AK, et al. Aetiological spectrum of chronic liver disease in eastern India.Trop Gastroenterol. 2000 Apr-Jun;21(2):60-2.

- Dhiman RK, Duseja A. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. In: Medicine Update (Diamond APICON). Eds. Gupta SB. 2005;15:469-75.

- Mihas AA, Toussaint J, Hsu HS, Dotherow P, Achord JL. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhosis: clinical and laboratory features, survival and prognostic indicators. Hepatogastroenterology 1992;39:520–522.

- Chavez-Tapia NC, Barrientos-Gutierrez T, Tellez-Avila FI, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for cirrhotic patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding (Review). Cochrane Library 2010; 9:1-67.

- D’Amico G, Garcia-Tsao G, Pagliaro L. Natural history and prognostic indicators of survival in cirrhosis: a systematic review of 118 studies. J Hepatol. 2006; 44:217–31

- Tandon P, Garcia-Tsao G. Renal dysfunction is the most important independent predictor of mortality in cirrhotic patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Clin GastroenterolHepatol. 2011; 9:260–5

- O’Grady JG, Schalm SW, Williams R. Acute liver failure: redefining the syndromes. Lancet. 1993;342:273–275.