48uep6bbphidcol2|ID

48uep6bbphidvals|1935

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GIST) are rare entities with malignant potential. They accounts for 1% of all primary gastrointestinal (GI)tumours. They are the most common mesenchymal neoplasms of the GI tract. As reported by Nilsson et al, epidemiological data is virtually non-existent regarding the true incidence and prevalence of GIST1. This is due to the previous lack of well-defined pathologic criteria for GIST, their varying nomenclature over the past few decades, and the finding that nearly 60% of all GIST have been diagnosed as benign tumours or tumours of uncertain malignant potential due to which they are not reported to national cancer registries1. We present the case of an anal GISTtreated by local excision so as to discuss the diagnosis, surgical treatment and adjuvant therapy of these rare lesions.

Case Report

A 75-year-old female presented to the surgery outpatient department with complaints of irregular bowel habits, constipation, dark coloured stools mixed with the blood and pain during defecation for 6 months. The pain was non-radiating, dull aching, persistent and increased with atraining for stool. The blood in the patient’s stool was frank red and came as drops after passage of stool. There was no tenesmus, no dizziness or weakness There was no significant relief in symptoms with medication. The patient had no prior history of hemorrhoids/diabetes mellitus/hypertension/tuberculosis/or any other chronic ailment was ruled out. There was no weight loss or loss of appetite.

On digital rectal examination, a hard indurated, nontender, well defined mass of 3×2 cm mass was felt at 6 o’clock to 9 o’clock position, starting from the anal verge. The mass had a bosselated surface, and it was mobile over the surrounding planes. Endo-anal ultrasound showed a left lateral isoechoic lump, with central calcification, extending from the inferior anal canal to the pubo-rectalis muscle. The lump was well circumscribed in the inter-sphincteric plane, pushing the external anal sphincter, with no evidence of invasion or infiltration of the surrounding tissues. There was no local lymphadenopathy. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed a well circumscribed, solid lump in the inter-sphincteric plane, without enlarged lymph nodes. The patient was planned for surgery and a local excision was performed through a radial incision. Only a few fibres of the internal anal sphincter were removed. The mass was encapsulated and not adherent to the surrounding structures.

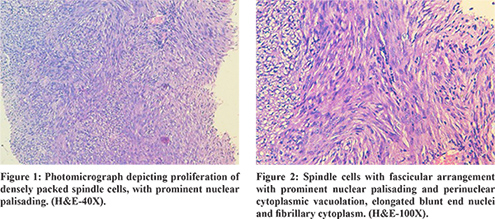

Gross pathological examination showed a 3×2×1 cm fibrous-elastic mass, and histological examination showed a proliferation of densely packed spindle cells, with prominent nuclear palisading (Figure 1). Nuclear atypia was absent and the mitotic count was of 4 mitosis per 50 high power fields (HPF). Individual tumour cells showed oval to spindle nuclei, finely dispersed chromatin, small inconspicuous nucleoli and vacuolated cytoplasm which partly to completely surrounded the nucleus. Occasional areas of interlacing bundles of uniform spindle cells with fascicular arrangement with prominent nuclear palisading and perinuclear cytoplasmic vacuolation, elongated blunt end nuclei and fibrillary cytoplasm was also seen (Figure 2). On immunohistochemistry (IHC), the neoplastic cells showed diffuse and marked cytoplasmic positivity for KIT protein, CD34 and vimentin (Figure 3). The neoplastic cells were negative for desmin and S100. A schwannoma, Ewing sarcoma, leiomyoma, spindle cell carcinoma, and epithelial malignancy were, thus, rendered unlikely. A final diagnosis of GIST with low malignant potential was made. The post-operative course was uneventful. No anal incontinence was observed and the patient was discharged on post-operative day 3. The patient was followed up at 6 and at 12 months. Both rectal ultrasonography as well as CT scan at follow up did not show local recurrence or distant spread. After five years, the patient is well, and there is no clinical or imaging evidence of recurrence.

Discussion

The term GIST was first used in 1983 to describe an unusual type of non-epithelial tumour of GI tract that lack the traditional features of smooth muscle or Schwann cells1. They arefound most often in the stomach (60%-70% of cases) and less frequently in the small intestine (30% of cases), while the rectum and anus are extremely rare locationsaccounting for 5% of all GISTs. Anal GISTs are evenrarer representing only 3% of all anorectal mesenchymal tumours. The vast majority of anorectal GISTs afflict malesin the fifth to seventh decades of life. Approximately half of the anorectal GISTs are incidental findings on colonoscopy or barium enema. Patients who are symptomatic may present with rectal bleeding, pain, change in bowel habits, signs of obstructionor urinary symptoms akin to prostatitis2. Literature issparse on the imaging of anal canal GISTs which are usually described as lesions in the inter-sphincteric space.

The presence of interstitial Cajal like cells has been reported in several extraintestinal organs including urinary bladder, prostate, gallbladder, omentum, uterus, fallopian tube, atrial and ventricular myocardium. This may explain the development of extraintestinal GISTs1. The DNA study of the tumour cells demonstrates a high frequency of a mutation that leads to the constitutive activation of the KIT-tyrosine-kinase in the absence of stimulation by its physiologic ligand. This causes an uncontrolled stimulation of downstream signalling cascades with aberrant cellular proliferation and resistance to apoptosis. In a small percentage of cases mutations in another tyrosine-kinase receptor (PDGFRa) have been demonstrated. The mutational status of c-KIT and PDGFR?? genes are the basis for the diagnosis of this neoplasm and represents the criteria for surgical therapy andpredicting the response to chemotherapy as well as clinical outcomes2. The final diagnosis is based on the histomorphological findings and the demonstration of immunoreactivity to c-KIT oncoprotein. Approximately 95% of GISTs are immunoreactive for c-KIT (CD117), whereas another 10% have activating mutations in the PDGFRA gene2. Approximately 5%-10% of GISTs appears to be negative for both c-KIT and PDGFR-A mutations. Fletcher’s criteria are proposed for their simplicity and wide acceptability. Fletcher’s criteria for measuring malignant potential of GISTs are based on size of the tumour and mitotic activity. The commonly accepted criteria to predict the malignant potential of a GIST are the mitotic activity (>5 mitotic figures/50 high power field) and the tumour size (>5 cm). Changchien identified age below 50 and size more than 5 cm as independent prognostic markers. The best indicator of malignancy is the presence of invasion of adjacent organs or obvious metastatic diseaseseen on imaging or surgery. Mucosal invasion and tumour necrosis have found to be related to increased risk of aggressive behaviour, but their clinical value remains uncertain. It should be noted that the guidelines proposed by Fletcher et al. recommend dividing GISTs into risk categories, emphasizing that no lesion can be definitely labelled as benign3.

The differential diagnoses for GISTS are schwannoma, Ewing sarcoma, leiomyoma, spindle cell carcinoma, and epithelial malignancy. Schwannomas show typical Antoni A and Antoni B areas with hyalinized blood vessels. The IHC stain was positive for S-100 protein. True smooth muscle tumours (leiomyosarcoma) are hypercellular tumours with haphazard arrangement of spindle cells with the high mitotic activity and necrosis. On IHC, they stain positive for SMA. Spindle cell carcinomas and epithelial malignancies characterized by areas of epithelial differentiation and show cytokeratin immunoreactivity.

GISTs are best treated by surgery. However, controversy exists whether abdominoperineal resection (APR) or conservative surgery is the best alternative. Although the incidence of local recurrence is lower after APR, the distant metastasis and survival are not significantly different4. Local recurrence frequently precedeslate spread to the liver, lungs and bone, and has been attributedto inadequate surgical clearance. Some authors recommend APR for GISTs larger than 2 cm4. Local excision may bean acceptable treatment option in selected patients, withtumours< 2 cm and < 5 mitoses/50 HPF on frozen section(5). Extensive lymph node dissection is unnecessary because GISTs rarely metastasise to the regional lymphnodes.Local excision has the advantage of minimal morbidity and sphincter preservation, while radical excision may offer a better oncological cure5. However, the method of resection did not significantly affect the development of metastasis or survival, as the number of metastases and deaths were similar with both surgical methods4. The role of adjuvanttherapy is still uncertain. Neither radiotherapynor conventional chemotherapy have any provenefficacy as adjuvant therapy5. Inhibitors of the tyrosine-kinase receptor, such asimatinib mesylate, represent the targeted therapy for localand distant recurrence after surgical resection. Although inhibitors of the tyrosine kinasereceptor need further study before they are routinely used as adjuvant therapy, their role in cases of distantor local recurrence has been accepted2. Close patient follow-up is mandatory to detect local recurrence and metastases assoon as possible. A longlatency period is common between the primary surgery and recurrences and metastases. It is not rare to have recurrences 10 years after resection of the primary tumour. Therefore, all patients with anorectal GIST should be regularly followed up for an indefinite period. If recurrent diseaseis detected, further excision can be attempted, for cure orfor palliation. For unresectable primary or recurrent GIST, the use of imatinib has been shown to be effective inreducing tumour volume and controlling disease progression5.

To the best of our knowledge, only twelve cases of c-KIT positive GIST of the anal canal have been reported in literature. Anorectal GIST, though rare, should be considered in the differential diagnoses of tumours in this region, especially if the pre-operative biopsy is equivocal. Gross and histopathological are both important, as prognosis depends on the tumour size as well as grade. However, the prognosis is usually better than for corresponding carcinomas in the region. Immunohistochemistry is a must, as the CD-117 score is not only diagnostic but also guides adjuvant therapy and is an important prognostic marker.

Conclusions

Anorectal GIST, although rare, should be considered in the differential diagnosis of tumours in this region. Immunohistochemistry is a must, as the CD-117 score is not only diagnostic but also guides adjuvant therapy and is an important prognostic marker. A close follow-up of patients is mandatory to screen for local recurrence or metastases. The role of adjuvant therapy is still uncertain. Although inhibitors of the tyrosine-kinase receptor need further studies before they are used routinely as adjuvant therapy, their role in cases of distant or local recurrence has been accepted.

References

- Nilsson B, Bumming P, Meis-Kindblom JM, Oden A, Dortok A, Gustavsson B, Sablinska K, Kindblom LG. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: the incidence, prevalence, clinical course, and prognostication in the preimatinib mesylate era – a population based study in western Sweden. Cancer 2005, 103:821-9.

- Li JC, Ng SS, Lo AW, Lee JF, Yiu RY, Leung KL. Outcome of radical excision of anorectal gastrointestinal stromal tumors in Hong Kong Chinese patients. Indian J Gastroenterol 2007; 26: 33-5

- C. R. Changchien, M. C.Wu, W. S. Tasi et al. “Evaluation of prognosis for malignant rectal gastrointestinal stromal tumor by clinical parameters and immunohistochemical staining,” Diseases of the Colon and Rectum 2004; 47:1922–9.

- Nigri GR, Dente M, Valabrega S, Aurello P, D’Angelo F, Montrone G, Ercolani G, Ramacciato G. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the anal canal: an unusual presentation. World J Surg Oncol 2007; 5: 20.

- Rattan KN, Kajal P, Malik VS, Soni Gargi. Multiple gastrointestinal and extragastointestinal stromal tumors in a male infant- an extreme rarity. Tropical gastroenterology 2012; 33:285-7.