48uep6bbphidcol2|ID

48uep6bbphidvals|1750

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Introduction

Leptospirosis is a zoonotic disease with worldwide distribution.

1-3 Previously thought to be a disease of rural population and sewage workers, it is re-emerging as a potentially life threatening disease in urban populations. Although it is endemic in southern and western parts of India,

4-6 leptospirosis has also been recently reported from eastern and northern India, where it was earlier thought to be non-existent.

7-14 Despite being common, the diagnosis of leptospirosis is often ignored or delayed because of low index of suspicion and protean presentation. Leptospira infection often has minimal or no clinical manifestations, with about 40% of the infected patients seroconverting asymptomatically. Of the remaining 60%, approximately 90% suffer the milder anicteric form and 10% the more severe icteric form

2-4 The severe form is associated with multi-organ involvement, especially hepato-renal, and a fatality rate of up to 40%.

5 Hepatic involvement in leptospira infection is not uncommon, and can vary from asymptomatic rise in transaminases to severe icteric hepatitis. However, detailed data on the frequency, degree and type of hepatic dysfunction in leptospirosis are limited. Very few studies have focussed on hepatic dysfunction in leptospirosis, and only a single study has evaluated the effect of leptospira infection in patients with pre-existing liver cirrhosis.

15-16 Cases of acute liver failure due to leptospirosis have also been reported.

17-18 This study aimed to analyse the hepatic dysfunction due to leptospirosis in both cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic patients, and to find the predictors of mortality in these patients.

Methods

The study was conducted a tertiary care institute located in Punjab, a northern Indian state which has an ideal environment favouring growth of leptospira with more than 66% of population residing in rural areas, widespread water logging during rainy season, abundance of rodents and presence of pets in the houses. Medical records of consecutive serologically confirmed cases of leptospirosis admitted to over one year period were screened. Detailed analysis of the clinical and laboratory profile with special emphasis on hepatic dysfunction was performed.

The clinical possibility of leptospirosis was considered in patients presenting with fever and associated symptoms like headache, myalgias, conjuctival suffusion or meningsmus with/without other symptoms like jaundice, hemorrhagic manifestations, reduced urine output, respiratory symptoms or convulsions.

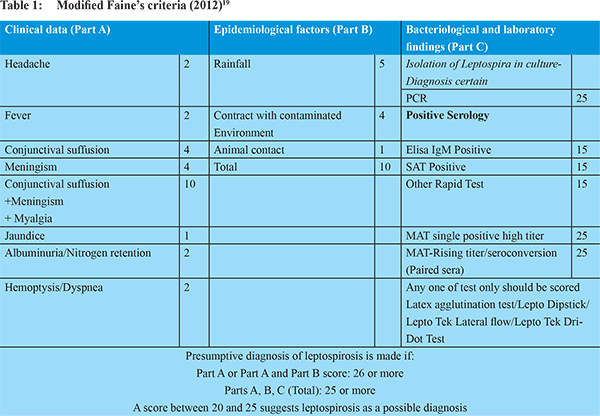

2 In addition, patients who had unexplained renal failure or hepatic dysfunction in the absence of fever were also screened for leptospira infection. Blood samples were tested for IgM anti-leptospira antibodies by quantitative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Panbio, Inverness Medical Innovations, Australia). As per manufacturer’s specifications, serological sensitivity and specificity of this kit are 96.5% and 98.5% respectively. Diagnosis of leptospirosis was made with a modified Faine’s score > 25 (

Table 1).

19 All patients were treated with specific drugs for leptospirosis (ceftriaxone or penicillin) in addition to supportive treatment. Cirrhosis was diagnosed based on clinical, biochemical, radiological and/or endoscopic criteria.

Patients with co-infections known to cause acute hepatitis (diagnosed by positive IgM HAV, IgM HEV, IgM anti HBc, malaria antigen, Widal test or blood culture for any bacterial/fungal organism) were excluded. Patients who had previously decompensated cirrhosis (Child Pugh B and C), hepatocellular cancer (HCC) or pre-existing chronic kidney disease (CKD) were also excluded.

Hepatic involvement due to leptospira was considered if there was more than two fold (> 80 IU/ml) rise in the liver enzymes alanine transaminase (ALT) or aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and/or conjugated hyperbilirubinemia of >2 mg/dl. Renal involvement was defined as serum creatinine or urea more than upper limit of normal (ULN). Hepato-renal involvement was defined as both liver and renal involvement according to above-mentioned criteria. Pulmonary involvement was defined as presence of symptoms like breathlessness/cough/hemoptysis, or imaging studies showing parenchymal infiltrates/pleural effusion. Central nervous system (CNS) involvement was defined as presence of altered sensorium or seizures.

Statistical analysis was done using the Fischer’s exact test and student’s unpaired t-test for significance of difference in proportions and means between two groups, respectively. Multiple regression coefficient method was performed to identify the factors associated with mortality. Data are expressed as mean ± SD or percentages. P value of < 0.05 was considered significant. Institutional ethics committee approved the study.

Results

Patient characteristics

Medical records of 257 patients of leptospirosis were screened. Of these, 38 patients were excluded due to presence of co-infections, diagnosed or suggested by serological tests, including enteric fever (n=14), hepatitis E (n=11), dengue (n=8), acute hepatitis B (n=3) and malaria (n=2). Eleven patients were excluded due to previous decompensated liver disease, three due to CKD and one due to HCC. Remaining 204 patients were included for further analysis. Mean age was 45.2 ±11.4 years (range 18-82 years). Maximum number of patients (n=106;51.9%) were middle aged, belonging to the age group of 35-54 years. Male:female ratio was 4.1:1. About half of the patients (48.5%, n=99) belonged to rural areas.

The common presenting symptoms were fever (85.3%), myalgias (59.8%), yellowish discoloration of eyes (53.4%), reduced urine output (30.4%), haemorrhagic manifestations (21.1%) and breathlessness (17.6%). Gastrointestinal tract was the most common site of haemorrhage (16.1%, n=33), followed by skin rash/petechiea (8.8%, n=18). The commonly found physical signs were hepatomegaly (43.6%, n=89), splenomegaly (32.4%, n=66), ascites (44.1%, n=90), and pleural effusion (12.7%, n=26).

The mean (±SD) haemoglobin, total leukocyte count (TLC) and platelet count at admission were 10.9 ±2.1 gm/dl, 7263 ±412 cells/mm3 and 181 ±101 x1000/mm3 respectively. Leucocytosis (TLC >11000 cells/mm3) and leucopenia (TLC <4000 cells/mm3) were noted in 53.4% (n=109) and 4.4% (n=9) patients respectively. Low platelet counts of<150 x1000/mm3 and <100 x1000/mm3 were observed in 52.9% and 29.9% patients respectively. Mean platelet count of patients with haemorrhagic manifestations was not significantly different from those without haemorrhage (141.5 ±111.5 vs 176.1 ±134.1 x1000/mm3 respectively;p=0.193).

Overall, hepatic dysfunction was present in 72.5% (n=148) patients. Percentage of patients having total bilirubin >2mg/dl was 72.5% (n=148). AST, ALT and ALP were increased (>2 ULN) in 60.1% (n=123), 60.1% (n=123) and 16.2% (n=33) respectively. Serum albumin was <3.5 g/dl in 71.1% (n=145) while PT/INR was >1.5 in 64.7% (n=132) patients. Mean(±SD) values of total bilirubin, AST, ALT, ALP, albumin and INR were 9.1 ±8.9 mg/dl, 229.9 ±733.9 IU/L, 177.4 ±498.6 U/L, 163.8 ±147.6 U/L, 2.6 ±0.6 g/dl and 2.3 ±1.1 respectively.Mean value of AST and ALT were not significantly different from each other (p=0.403). Mean INR value of patients with bleeding manifestation was not significantly different from those without bleed (2.7 ±1.7 vs 2.2 ±1.4 respectively;p=0.057).

Comparison between cirrhotics and non-cirrhotics

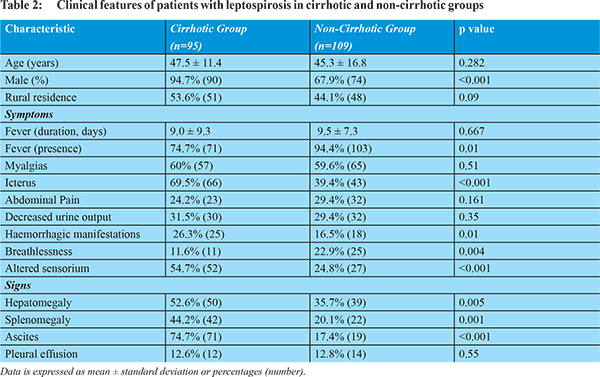

Underlying cirrhosis of liver was present in 46.6% (n=95) patients. A comparison between clinical and laboratory features of leptospirosis patients with cirrhosis (group A) and without cirrhosis (group B) is shown in Tables 2 and 3. The percentage of patients presenting with icterus, haemorrhagic manifestations, altered sensorium and/or ascites was significantly more in group A, while percentage presenting with fever and/or breathlessness was significantly more in group B. Rare complications like acalculus cholecystitis was diagnosed in two patients in group A and one in group B; while acute pancreatitis without any other identifiable etiological factor was diagnosed in one patient in each group.

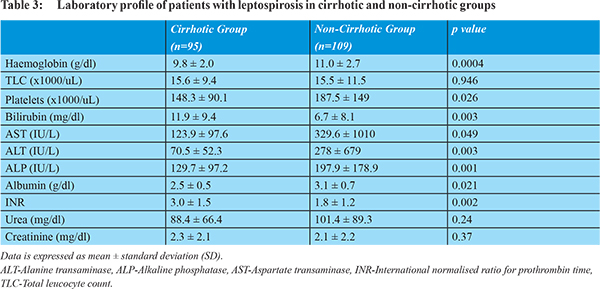

There were significant differences in liver functiontests and platelet countsbetween both groups (Table 3). Mean bilirubin and INR were significantly higher, while mean ALT, AST, ALP, albumin and platelets were significantly lower in group A, as compared to group B. Serum bilirubin >2 mg/dl was seen in significantly more patients in group A compared to group B (91.6% vs 61.5%, p=0.0001). On intra-group comparison of the mean ALT and AST values, it was found that AST was significantly higher than ALT in group A (123.9 ±97.6 U/L vs 70.5 ±52.3 U/L, p=0.0001), while they were not significantly different in group B (329.6 ±1010 U/L vs 278 ±679 U/L, p=0.668).

Comparison of various organ system involvements among cirrhotics and non-cirrhotics is shown in Figure 1. The percentage of patients with renal involvement was not significantly different between the two groups A and B (64.2% vs 56.9%, p=0.89), while percentage of patients with hepato-renal involvement was significantly more in the group A (58.9% vs 43.8%, p=0.024). Percentage of patients with CNS involvement (altered sensorium) in group A was significantly more as compared to group B (54.7% vs 24.8%, p<0.001]. No patient had convulsions or complications of meningitis. Percentage of patients with pulmonary involvement was not significantly different between the two groups (33.6% vs 44%, p=0.4).

Mortality in patients of leptospirosis

Mortality rate in the group A was significantly higher than that in group B (29.5% vs17.4%, p=0.047). Sub-group analysis showed that the mortality rate of patients with un-complicated leptospirosis in the group B (2.8%;1/35) was much lower than patients with hepato-renal involvement [35.7% (20/56),p=0.0002 and28.2% (13/46), p=0.0026 in group A and B respectively].

The univariate and multivariate analysis of factors predicting mortality in leptospirosis patients is shown in Table 4. On univariate analysis, the factors which predicted mortality were- age >40 years, bilirubin >10 mg/dl, creatinine >2 mg/dl, need for hemodialysis, need for artificial ventilation, hepato-renal involvement and presence of underlying cirrhosis. On multivariate analysis, it was found that need for artificial ventilation, hepato-renal involvement and presence of underlying cirrhosis were predictors of mortality.

Discussion

Leptospirosis is a global health problem affecting both rural and urban populations in the developing as well as developed countries.

5 It is frequently under-diagnosed because of its protean manifestations, difficulty in distinguishing it from other febrile illnesses, lack of awareness or the lack of availability of diagnostic tests. In absence of adiagnosis, many cases of leptospirosis may be going unnoticed leading to acute fatal illness and chronic health effects like migraine, uveitis, chronic fatigue and depression.

4 Early occurrence of complications such as hepatitis mandates caution in the primary care setting.

15 Our study describes in detail, the hepatic manifestations of leptospirosis, and compares the differences in presentation and outcome of leptospirosis in patients with and without underlying liver cirrhosis.

In the present study, a large proportion (nearly 47%) of hospitalised patients with leptospirosis had underlying cirrhosis. This raises the question whether cirrhotics are more prone to acquire and/or manifest leptospirosis? It is already known that patients with cirrhosis are particularly susceptible to acquire infections due to various organisms like viruses, bacteria, parasites, spirochetes or fungi because of abnormal immune defence mechanisms including complement deficiency, reduced chemo-attractant activity, decreased phagocytic activity, impaired bactericidal function of IgM for certain bacteria, and a reduced number of Kupffer cells. However, this observation in our study may also be due to the healthcare seeking behaviour of previously sick patients, while the milder cases of leptospirosis in non-cirrhotics may remain undiagnosed. This fact needs to be confirmed in future studies.

In concordance with the existing literature,

7 we found that males were more commonly affected with leptospirosis both in the cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic groups, suggesting increased risk of transmission from occupational and recreational exposures. This was a hospital based study and not a community study and so a definite conclusion cannot be drawn yet the study suggests that as almost equal number of patients in the present study belonged to rural and urban areas, hence urban population is also at equal risk for acquisition of this disease, as reported by Kamath et al.

20 Fever is usually considered as a cardinal symptom of leptospirosis, and leptospirosis forms an important differential diagnosis of febrile illness in endemic areas. Studies from India have shown 15-38% seropositivity for leptospirosis amongst patients with febrile illness.

12,21 However, in the present study, history of fever was absent in 25.3% of the cirrhotics and 5.6% of the non-cirrhotics with leptospirosis. Similar reports of afebrile leptospiral infection have been reported by other authors.

22,23 In a study by the Hawaii department of health, 5% of patients gave no history of fever, and 55% were afebrile at the time of presentation.

23 This data suggests that fever may be more frequently mild or absent in leptospirosis than previously described. Therefore, screening for leptospirosis should be done even in afebrile patients presenting with unexplained involvement of other organ systems, especially in cirrhotics with unexplained decompensation of the liver.

Haemorrhagic manifestations of leptospirosis range from petechiae to bleeding from serosa and mucosa,

24 and have been reported in about 50% of the cases.

25 As in the case of haemorrhage in dengue fever,

26 another common febrile illness in the tropics, exact cause of bleed in leptospirosis is not clear. Thrombocytopenia and elevations in PT/INR may occur but are not a consistent finding in patients with bleeding, and do not appear causally related.

3,24 The other proposed mechanisms for bleed are capillary vasculitis and leakage, and coagulation factordeficiency secondary to liver involvement.

24 The presence of jaundice in hospitalised cases of leptospirosis has varied from 32% to 84%.

27-29 Hepatic necrosis caused by ischemia and destruction of hepatic architecture leads to characteristic jaundice of severe leptospirosis.

3 In the present study, jaundice was present in 91.6% of the cirrhotics and 61.5% of the non-cirrhotics. The mean serum bilirubin was 9.1 mg/dl, which is similar to that reported in previous studies.

7,24 The mean serum bilirubin level was significantly higher in patients with underlying cirrhosis compared to those without cirrhosis, similar to previous studies.

15 The mean serum transaminases values in our study were similar to that reported by Sethi et al

7 but higher than those reported by Clerke et al [40-50 U/L].

24 The magnitude of AST and ALT rise was higher in non-cirrhotics compared to cirrhotics. In non-cirrhotic patients, both AST and ALT were found to be proportionately elevated, in contrast to the hepatic involvement in dengue fever in which AST values are significantly higher than ALT values.

30 This liver function profile may act as an early indicator of diagnosis in a patient with fever and thrombocytopenia and help in early institution of specific therapy.

Renal involvement is common in leptospirosis and has varied from 16% to 72%.27,28 We noticed renal involvement in about 60% patients. Renal involvement was not different among cirrhotics and non-cirrhotics, indicating that the presence of cirrhosis did not affect renal involvement due to leptospirosis in our study. In contrast, renal involvement was found to be more common among cirrhotics in another study.

15 Izurieta et al have reported that the risk of developing renal failure increases with the increasing severity of jaundice.

4 Pulmonary involvement in leptospirosis is well documented, and has been reported in up to 37% patients.

27 In our study, 33.6% and 44% of the cirrhotics and non-cirrhotics respectively had pulmonary involvement. Pulmonary findings are caused by alveolar capillary injury, and may occur in absence of hepatic and renal failure.

31-33 In our study about 2% patients had pulmonary involvement in absence of renal or hepatic involvement.

Aseptic meningitis has been reported as the most common neurological abnormality in leptospirosis.

34,35 Chawla et al has reported altered sensorium in 36.6% patients of leptospirosis.

33 In the present study, 38.7% patients had altered sensorium. No patient had convulsions or complications of the meningitis. The presence of altered sensorium was significantly more common among cirrhotics, possibly due to hepatic decompensation leading to hepatic encephalopathy in patients with underlying cirrhosis, rather than a neurological manifestation of leptospirosis. CSF analysis was not performed as all the patients improved with treatment of leptospirosis alone.

Uncommon presentations of leptospirosis including acalculus cholecystitis and leptospiral pancreatitis have been documented in literature.

36,37 In present study, 3 patients had acute acalculus cholecystitis and 2 had acute pancreatitis associated with leptospira infection, all of whom improved with conservative management.

The mortality rate in leptospira infection ranges from <5% in un-complicated disease to >40% in patients with hepato-renal involvement.

3,38 Similar results were seen in the present study, in which mortality rate among patients with un-complicated leptospirosis was 2.8%, with while it was much higher among patients with hepato-renal involvement (35.7% and 28.2% in the cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic groups respectively). Pulmonary and renal involvement are known predictors of mortality.

39,40 Some studies found hypotension, haemorrhage, cardiovascular collapse, male gender, old age, alcohol intake, hight ALT, high bilirubin, metabolic acidosis and need for ventilatory support to be predictors of poor prognosis.

3,14,31,41 In the present study, hepato-renal involvement, presence of underlying cirrhosis and need for artificial ventilation were predictors of mortality. Similar results have been reported by Somasundaram et al15 where all the deaths were due to cirrhosis and hepato-renal involvement.

We used ELISA technique for microbiological diagnosis of leptospirosis as it has now emerged as a reliable diagnostic test with good specificity and sensitivity, and has good correlation with MAT (microscopic agglutination test).

3,4,42-44 MAT is now-a-days used as a diagnostic tool for serovar specific diagnosis only, as it involves hazardous live bacteria, and is time consuming. The value of culture is limited because samples must be collected before the administration of antibiotics, and culturing requires prolonged incubation.

Another important fact that this study highlights is that leptospirosis is an important cause of hepatic decompensation in cirrhotics. Similar data has been reported by Somasundaram et al.

15 Therefore, leptospirosis should be kept as a differential diagnosis in a cirrhotic patient presenting with decompensation of liver disease, especially if other common causes are ruled out.

Our study has some potential limitations. First, it was a retrospective study. Second, the patients were recruited from a single medical centre. However, since our institute is one of the major referral centres of northern Indiapatients included in this study had a wide geographical distribution. Third, we did not study the patients of decompensated cirrhosis in our study as it is difficult to assess the hepatic dysfunction due to leptospirosis in these patients.

On the other hand, our study has various strengths. First, it is one of the largest clinical studies on human leptospirosis from India. Secondly, it is one of the few studies that documents and compares the complete clinical profile and outcome of leptospirosis in cirrhotics and non-cirrhotics. Third, both groups in our study were of adequate size, leading to good reliability and applicability of our findings.

Conclusion

To conclude, hepatic dysfunction in leptospirosis is common, and occurs more frequently in patients with underlying cirrhosis. Cirrhotics with leptospirosis are less likely to present with fever, have higher chances of hepato-renal and neurological involvement, and have significantly higher mortality compared to non-cirrhotics. Hepato-renal involvement, presence of underlying cirrhosis and need for artificial ventilation are predictors of poor outcome. Therefore, cirrhotics with unexplained decompensation of liver disease should be screened early for leptospira infection even in the absence of fever.

References

- Levett PN. Leptospirosis. Clin Microbiol Reviews. 2001;14(2):296-326.

- Dutta TK, Christopher M. Leptospirosis- an overview. J Assoc Physicians India. 2005;53:545-51.

- Rao R, Sambasiva, Gupta N et al. Leptospirosis in India and the rest of the world. Braz J Infect Dis. 2003;7:178-93.

- Izurieta R, Galwankar S, Clem A. Leptospirosis: the mysterious mimic. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2008;1:21-33.

- Vijayachari P, Sugunan AP, Shriram AN. Leptospirosis: an emerging global public health problem. J Biosci. 2008;33:557-69.

- Sehgal SC. Leptospirosis in the horizon. Natl Med J India. 2000;13:228-30.

- Sethi S, Sharma N, Kakkar N et al. Increasing trends of leptospirosis in north India: a clinico-epidemiological study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010; 4: e579. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000579.

- Manocha H, Ghoshal U, Singh SK et al. Frequency of leptospirosis in patients of acute febrile illness in Uttar Pradesh. J Assoc Physicians India. 2004;52:623-5.

- Gupta N, Rao RS, Bhalla P et al. Seroprevalence of leptospirosis in Delhi using indirect haemagglutination assay. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2004;22:134-5.

- Sethi S, Sood A, Pooja et al. Leptospirosis in northern India: a clinical and serological study. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2003;34:822-5.

- Chaudhry R, Premlatha MM, Mohanty S et al. Emerging leptospirosis, North India. Emerg Infect Disease. 2002;8:1526-7.

- Kaur IR, Sachdeva R, Arora V et al. Preliminary survey of leptosporosis amongst febrile patients from urban slums of East Delhi. J Assoc Physicians India. 2003;51:249-51.

- Chauhan V, Mahesh DM, Panda P et al. Profile of patients of leptospirosis in sub-Himalayan region of North India. J Assoc Physicians India. 2010 Jun;58:354-6.

- Goswami RP, Goswami RP, Basu A et al. Predictors of mortality in leptospirosis: an observational study from two hospitals in Kolkata, eastern India. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2014;108:791-6.

- Somasundaram A, Loganathan N, Varghese J et al. Does leptospirosis behave adversely in cirrhosis of the liver? Indian J Gastroenterol. 2014;33:512-6.

- Pappachan MJ, Mathew S, Aravindan KP et al. Risk factors for mortality in patients with leptospirosis during an epidemic in northern Kerala. Natl Med J India. 2004;17:240-2.

- Sarkar J, Chopra A, Katageri B et al. Leptospirosis: a re-emerging infection. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2012;5:500-2.

- Covic A, Maftei ID, Gusbeth-Tatomir P. Acute liver failure due to leptospirosis successfully treated with MARS (molecular adsorbent recirculating system) dialysis. Int Urol Nephrol. 2007;39:313-6.

- Shivakumar S. Indian Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Human Leptospirosis. API Medicine Update. 2012;22:23-9.

- Kamath SA, Joshi SR. Reemerging of infection in Urban India - Focus Leptospirosis. J Assoc Physicians India. 2003;51:247-8.

- Ratnam S, Sunderaraj T, Thyagarajan SP et al .Serological evidence of leptospirosis in jaundice and pyrexia of unknown origin. Indian J Med Res. 1983;77:427-30.

- Perrocheau A, Perolat P. Epidemiology of leptospirosis in New Caledonia (South Pacific): a one-year survey. Eur J Epidemiol. 1997;13:161-7.

- Sasaki DM, Pang L, Minnette HP et al. Active surveillance and risk factors for leptospirosis in Hawaii. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;48:35-43.

- Clerke AM, Leuva AC, Joshi C et al. Clinical profile of Leptospirosis from Gujrat. J Postgrad Med. 2002;48:117-8.

- Ragnaud JM, Morlat P, Buisson M et al. Epidemiological, clinical, biological and developmental aspects of leptospirosis: apropos of 30 cases in Aquitaine. Rev Med Interne. 1994;15:452-9.

- Chhina DK, Goyal O, Goyal P et al. Haemorrhagic manifestations of dengue fever & their management in a tertiary care hospital in north India. Indian J Med Res. 2009;129:718-20.

- De A, Varaiya A, Mathur M et al. An outbreak of leptospirosis in Mumbai. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2002;20:153-5.

- Muthusethupathi MA, Shivakumar S, Suguna R et al. Leptospirosis in Madras- a clinical and serological study. J Assoc Physicians India. 1995;43:456-8.

- Datta S, Sarkar RN, Biswas A et al. Leptospirosis: an institutional experience. J Indian Med Assoc. 2011;109:737-8.

- Chhina RS, Goyal O, Chhina DK et al. Liver function tests in patients with dengue viral infection. Dengue Bulletin. 2008;32:110-7.

- Chawla V, Trivedi TH, Yeolekar ME. Epidemic of Leptospirosis: An ICU Experience. J Assoc Physicians India. 2004;52:619-22.

- Courtin JP, Di Francia M, Du Couedic I et al. Respiratory manifestations of leptospirosis. A retrospective study of 91 cases (1978-1984). Rev Pneumol Clin. 1998;54:382-92.

- Zaki SR, Shieh W J. Leptospiros is associated with outbreak of acute febrile illness and pulmonary haemorrhage, Nicaragua, 1995. The Epidemic Working Group at Ministry of Health in Nicaragua. Lancet. 1996;347:535-6.

- Heath CW Jr, Alexander AD, Galton MM. Leptospirosis inthe United States: analysis of 483 cases in man, 1949-1961. N Engl J Med. 1965;273:915-22.

- Panicker JN, Mammachan R, Jayakumar RV. Primary neuroleptospirosis. Postgrad Med J. 2001;77:589-90.

- Wang NC, Ni YH, Peng MY, Chang FY. Acute acalculous cholecystitis and pancreatitis in a patient with concomitant leptospirosis and scrub typhus. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2003;36:285-7.

- Chong VH, Goh SK. Leptospirosis presenting as acute acalculous cholecystitis and pancreatitis. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2007;36:215-6.

- Taylor AJ, Paris DH, Newton PN. A Systematic Review of the Mortality from Untreated Leptospirosis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015 Jun 25;9(6):e0003866. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0003866. eCollection 2015.

- Panaphut T, Domrongkitchai S, Thinkamrop B. Prognostic factors of death in leptospirosis: a prospective cohort study in KhonKaen, Thailand. Int J Infect Dis. 2002;6:52-9.

- Dupont H, Dupont-Perdrizet D, Perie JL et al. Leptospirosis: prognostic factors associated with mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:720-4.

- Rajapakse S, Weeratunga P, Niloofa MJ et al. Clinical and laboratory associations of severity in a Sri Lankan cohort of patients with serologically confirmed leptospirosis: a prospective study. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2015 Nov;109(11):710-6. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trv079.

- Winslow WE, Merry DJ, Pirc Moira et al. Evaluation of a commercial enzyme -linked immunosorbent assay for detection of Immunoglobulin/M antibody in diagnosis of humanleptospiral infection. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1938-42.

- Cumberland P, Everard CO, Levett PN. Assessment of the efficacy of an IgM-ELISA and microscopic agglutination test (MAT) in the diagnosis of acute leptospirosis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61:731-4.

- Budihal SV, Perwez K. Leptospirosis diagnosis: competency of various laboratory tests. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:199-202.