|

Hasan S. Mahmoud1, Ali AS. Ghweil1, Ghada S. Osman2, Shamardan Ezz-Eldin S. Bazeed1, Mohamed M. Helal1

1Department of Tropical medicine and Gastroenterology, Qena Faculty of Medicine, South Valley University, 2Department of Pathology, Qena Faculty of Medicine, South Valley University, Egypt.

Corresponding Author:

Hasan Sedeek Mahmoud

Email: hasan_sedeek@yahoo.com

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.333

Abstract

Background: Hyaluronic acid (HA) is an attractive potential marker for noninvasive diagnosis of liver fibrosis instead of liver biopsy for both patients and physicians.

Aim: To assess the role of HA for diagnosing the progression of steatosis to steato-hepatitis (SH) and fibrosis in patients with Chronic Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.

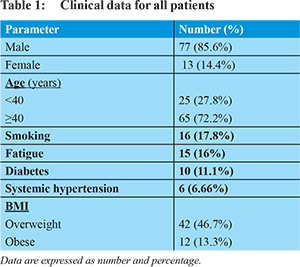

Methods: 90 patients with chronic HCV infection, 77 (85.6%) males and 13 (14.4%) females, were included. Blood samples were collected for routine laboratory investigations, liver function tests and serum HA measurements. A liver biopsy was taken for histopathological examination.

Results: Steatosis was found in 37 patients (41.1%), fibrosis in 29 patients (32.2%) and SH in 51 patients (56.7%). The mean serum HA for all patients was 86.4±48.2 ng/L. HA levels were significantly higher in patients with fibrosis (95.6±53 vs 54.5±3.5) and SH (88.7±52 vs 49.9±12) than those without (P value = 0.001and 0.001 respectively). HA levels were also significantly higher in patients with an advanced degree of fibrosis, SH and steatosis as compared to those with mild degrees (P value = 0.000, 0.001 and 0.01 respectively). Positive correlations were found between serum HA and the degree of fibrosis, SH and steatosis (P value =0.000 and r = + 0.758, 0.701and 0.727 respectively). The mean HA cut off value for the diagnosis of fibrosis and SH was taken to be 70 and 60 ng/L providing a diagnostic accuracy of 94.1% and 91.6% respectively.

Conclusions: Serum HA level is a good noninvasive marker for the diagnosis of fibrosis and steato-hepatitis in patients with chronic HCV infection.

|

48uep6bbphidcol2|ID 48uep6bbphidvals|1714 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Introduction

More than 185 million people around the world, according to recent estimates have been infected with Hepatitis C Virus(HCV), of whom 350000 die each year. 1,2 Egypt has the highest prevalence of HCV infection in the world, being 14.7%. 3 Liver biopsy is currently recommended as the gold standard method for staging fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. 4,5 The risk of developing cirrhosis depends on the stage (degree of fibrosis) and the grade (degree of inflammation and necrosis) observed in the initial liver biopsy. 6,7 This procedure, however, is invasive and has potential complications. 8,9 Non-invasive approaches developed to assess histological samples include clinical symptoms, routine laboratory tests, and radiologic imaging. 10,11 Several clinical studies have attempted to identify serum markers that correlate with the degree of fibrosis and could thus be used in conjunction with or in place of a liver biopsy. 9,12,13 In liver, hyaluronic acid (HA) is mostly synthesized by the hepatic stellate cells and degraded by the sinusoidal endothelial cells. 14 It has been shown that serum HA levels increase in chronic liver diseases and that progressive liver damage can be identified early by serum HA assessment. 15,16

The aim of the current study is to evaluate the role of HA in predicting steatosis, SH and fibrosis in patients with chronic HCV infection and to determine cut off value for the diagnosis of fibrosis and SH.

Methods

A cross sectional study was conducted on 90 patients with chronic HCV infection attending the outpatient clinic (Tropical Medicine and Gastroenterology, Qena faculty of medicine) from January 2011 to March 2013, who fulfilled our study criteria and accepted to be enrolled.Inclusion criteria: Chronic HCV infection was diagnosed by detecting both Anti-HCV and HCV RNA in serum and subsequently confirmed by liver biopsy. Exclusion criteria: Patients were excluded if any one of the following was found: evidence suggestive of liver cirrhosis on clinical or ultrasound (US) examination, detectable hepatitis B surface antigen or serologic evidence of other chronic liver diseases (such as autoimmune hepatitis, Wilson disease, etc.), history of alcohol intake, history of receiving potential hepatotoxic drugs and refusal to undergo a liver biopsy. All patients underwent clinical evaluation (including medical history and physical examination), laboratory investigations, abdominal ultrasonography and ultrasound guided percutaneous liver biopsy for histopathological examination.

Clinical Evaluation

A detailed medical history was taken including age and symptoms suggestive of chronic liver disease such as fatigue, joint pain, loss of libido, impotence, anorexia, weight loss, yellow colored sclera, light colored stool, dark colored urine, itching, lower limb swelling, bleeding, abdominal pain and abdominal swelling. History of past surgery or invasive medical procedures, history of transfusion of blood or blood products and history of liver disease in other family members were also recorded.On clinical examination, signs suggestive of chronic liver disease such as jaundice, pallor, ecchymosis, purpura, spider nevi, gynecomastia, palmar erythema, flapping tremors, lower limb edema, liver enlargement, spleen enlargement, ascites and hernias were noted.

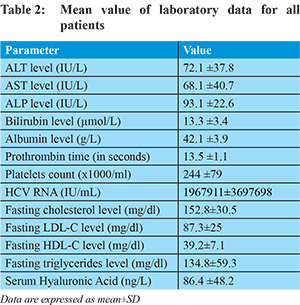

The following laboratory investigations were performed: Liver function tests (serum ALT, AST, ALP, bilirubin, total protein and serum albumin levels), prothrombin time and concentration, complete blood count, serum creatinine and glucose levels.

Specimen preparation: A serum separator tube was used and samples were allowed to clot for 10-20 minutes at room temperature before centrifugation for 20 minutes at the speed of 2000-3000 r.p.m. Serum was removed and assayed immediately or aliquots were taken and the samples stored at – 20 C0. The samples were centrifuged again after thawing before the assay. Serum Hyaluronic Acid (HA) was measured using HA ELISA kits (WKEA MED, CHINA). Purified human HA antibody was coated on the microtitre plate wells to make a solid-phase antibody. To this, was added the patient’s serum sample containing HA which bound to the HA antibody. This was followed by the addition of an enzyme labeled HA antibody resulting in the formation of an antibody - antigen (HA)- antibody (enzyme labeled) complex. After washing out the excess enzyme labeled HA antibody, substrate was added which turned the sample mixture blue when catalyzed by the enzyme horseradish peroxide (HRP). The reaction was then terminated by the addition of sulphuric acid. The colour change was measured spectrophotometrically at a wavelength of 450 nm. The concentration of HA in the sample was then determined by comparing the optical density of the sample to the standard curve.

Abdominal ultrasonography was performed in the ultrasound unit (Tropical Medicine and Gastroenterology Department, Qena University Hospital) using Toshiba TA 311 (Japan) for evaluation of the liver size, surface, and echopattern, portal vein diameter, gallbladder wall, spleen size and echopattern, splenic vein diameter and the presence or absence of ascites. Chronic hepatitis was suggested based on presence of hyperechoic 17 coarse echopattern. 18 Findings suggestive of NAFLD include a diffuse hyperechoic echopattern (bright liver) compared with kidneys, vascular blurring, and deep attenuation. 19

US Grades of Steatosis

Grade 1: Slight, diffuse increase of fine echoes in liver parenchyma.

Grade 2: Moderate, diffuse increase of fine echoes in liver parenchyma with slightly impaired visualization of intrahepatic vessels and diaphragm.

Grade 3: Marked increase in fine echoes in liver parenchyma with poor or non-visualization of intrahepatic vessels, diaphragm, and posterior right lobe of liver.

Ultrasound guided percutaneous liver biopsy: US guided percutaneous liver biopsy was performed using automatic (spring loaded, cutting needle, 18 gauge needle, Germany). All biopsies were performed in the interventional US unit (Tropical Medicine and Gastroenterology Department, Qena University Hospital).The were then delivered to the pathology laboratory (Pathology Department, Qena Faculty of Medicine) for histopathological examination.

Histopathological examination: Formalin fixed, paraffin embedded liver sections stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin stain and with special stains (Masson’s trichrome stain) were examined using Olympus BH-2 light microscope and digitally photographed using microscope attached Olympus E-330 zoom digital camera. The liver lesions were graded (grade of necroinflammation) and staged (stage of fibrosis) according to modified histological activity index (HAI) by Ishak and colleagues 20 whose scores were reformulated to be more easily used for routine practice. Steatosis was defined and graded according to Brunt scoring system. 21 NASH in patients with chronic HCV infection was defined by the presence of hepatocyte ballooning, Mallory hyaline bodies, and perisinusoidal. 22

Written consent was taken from all patients who were included in the study and the protocol for the study was approved by the local ethical committee of our faculty of medicine.

Statistical analysis: The data gathered has been presented descriptively as shown below. Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software for Windows, release 20. One way ANOVA test was used for comparison between HA and different grades of steatosis, SH and fibrosis. Correlations between different variables and HA were analyzed using Spearman correlation test. Regression analysis was done for HA to predict presence of fibrosis and SH. The sensitivity and specificity of the prediction rule were estimated by means of a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and the area under the curve (AUC) was reported.

Results

The demographic data for all patients are as shown in Table 1. The mean age of patients was 41.7±7.6 years. Smoking was found in 17.8% of patients. Fatigue was found in 16% of patients. History of DM was found in 11.1% and systemic hypertension in 6.6% of patients. Clinical examination revealed that 46.7% of patients were overweight and 13.3% were obese.Laboratory data for all patients including liver function tests, coagulation profile, lipid profile and mean serum HA are shown in Table 2. Abdominal ultrasound showed enlargement of the liver in 33.3%, hyperechoic liver echopattern in 46.7% and enlargement of the spleen in 5.6% of patients.Histopathological examination of all liver biopsies revealed the following: Steatosis was found in 41.1% of patients (the most frequent grade was grade 1, in 43.2% of those patients) and SH was found in 56.7%. The most frequent grade of NI was grade 1 in 34.4% of those patients and portal inflammation was the most frequent type which was found in 90% of those patients. Fibrosis was found in 32.2% of all patients and the most frequent type of fibrosis was portal fibrosis in 68.9% of those patients.

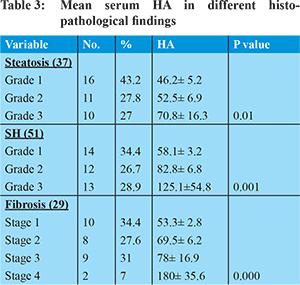

Hyaluronic acid: Mean serum HA for all patients was 86.4±48.2 ng/L. HA was significantly higher in patients with fibrosis (95.6±53vs54.5±3.5) and SH (88.7±52 vs 49.9±12) than those without (P value = 0.001and 0.001 respectively). HA was also significantly higher in patients with an advanced degree of fibrosis, SH and steatosis than those with mild degrees as shown in Table 3 (P value = 0.000, 0.001 and 0.01 respectively).

Positive correlations were found between serum HA and the degree of fibrosis, steatosis and SH (P value =0.000 and r= + 0.758, 0.727 and 0.701 respectively) as shown in Table 4. The mean HA cut off value for diagnosis of fibrosis and SH was taken to be 70 and 60 ng/L respectively providing significant sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value(NPV) and accuracy as is illustrated in Table 5. ROC curve was done to detect the role of HA in prediction of fibrosis and SH and the area under the curve was 0.94 for prediction of fibrosis and 0.92 for prediction of SH as is illustrated in Figures 1 and 2.

Discussion

It is estimated that approximately 130-210 million individuals, i.e. 3% of the world population, are chronically infected with HCV. 23,24 The prevalence varies markedly from one geographic area to another and within the population assessed. It is higher in Eastern Europe and the Middle East, though the numbers are not precisely known. 25 Community based Egyptian studies have found strong correlations between HCV infection and different medical exposures such as injections, blood transfusions, surgical procedures, perinatal care, and dental treatment. 26 For the last 50 years, liver biopsy has been considered the gold standard for the staging of liver fibrosis in spite of its many shortcomings such as intra- and inter-observer variability in histopathological interpretation, 27 sampling errors, 28 and potentially life-threatening complications. 29 Robert et al in 2009 reported that community pathologists understaged liver fibrosis in >70% of cases with chronic HCV infection. 30

Noninvasive diagnosis of liver fibrosis is an attractive alternative to liver biopsy for both patients and physicians. These markers are classified as direct (or class I) which represent extracellular matrix components reflecting the pathophysiology of liver fibrogenesis (procollagen type 1 and type III, Type IV collagen, Laminin and others) and indirect (or class II) which use routine laboratory data reflecting the consequences of the liver damage (ALT, AST/ ALT, AST/platelet ratio, Fibro test and Fibrosure, FIB-4 score and others) with different degrees of accuracy for diagnosis of fibrosis. 31 No true serum marker that would act as a surrogate marker of hepatic fibrosis has been validated till date. It is almost certain that combinations of biomarkers will have to be examined.

In the current study, we used hyaluronic acid (HA) as a noninvasive marker for the prediction of liver fibrosis in NASH patients with chronic HCV infection. HA is a component of the extracellular matrix that can be measured in the serum, where it reaches through the lymphatics. Serum levels are dependent on production thus increasing with an increase in collagen synthesis, as well as degradation, which takes place in the liver sinusoidal endothelial cells after binding to specific receptors. With progression of liver fibrosis, both increased production of collagen and decreased function of sinusoidal endothelial cells (with decreased degradation) lead to the elevation of HA levels in the serum. 32

We found statistically significant higher levels of serum HA in advanced stages of fibrosis (stage IV) than those with stage I. Our results are in accordance with those of Suzukiet al.(2005) and Miele et al.(2009) who reported that HA is a good marker of severe fibrosis in patients with NAFLD. 33,34 Raszeja-Wyszomirska et al.(2011) also reported that serum HA was an independent risk factor for more advanced fibrosis in their study patients. 35

Among Egyptian studies, our results agreed with those of Esmatet al. (2007) who reported that serum HA could be used as a single biomarker, fulfilling the criteria for a good predictor of fibrosis andthat young patients with low levels of serum HA were at a very low risk of fibrosis. 36

We also found statistically significant higher values of serum HA in patients with Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH) compared with patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD). These findings coincided with the results of Sakugawaet al. (2005) who found that when patients having fatty liver alone were compared with patients having NASH, serum HA was significantly different between the two groups. 37

In addition, we found significantly higher serum HA levels in patients with advanced necroinflammatory grade than those with mild necroinflammation. This was similar to the findings of Murawakiet al.(1995) who found that serum levels of HA have been shown to be related to the degree of necroinflammation. 38

Several mechanisms may contribute to the elevation of serum HA levels in these patients. At the beginning of disease development, the enhancement of HA production by the activated hepatic stellate cells may be responsible for the increase in its serum levels. 39 Later, in advanced stages of the disease when hepatic sinusoid capillarization and cirrhosis are established, reduced degradation of HA by sinusoidal endothelial cells may be the cause of greater HA increments. 40 It seems that the progression of liver fibrosis (and inflammation) was accompanied by impairment in the liver endothelial cell function and reduced degradation of this heteropolysaccharide, eventually resulting in elevation of serum HA concentrations. Hadi et al. (2009) reported that there was a strong positive correlation between the mean serum HA and liver fibrosis stages. Such a positive correlation was also found between the mean serum HA and liver inflammation grades. 41

Conclusion

Serum HA is a good noninvasive marker for the diagnosis of fibrosis and steato-hepatitis in patients with chronic HCV infection.

References

- Mohd Hanafiah K, Groeger J, Flaxman AD, Wiersma ST. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: new estimates of age-specific antibody to HCV seroprevalence. Hepatology. 2013;57(4):1333-42.

- Lavanchy D. The global burden of hepatitis C. Liver Int. 2009;29 Suppl 1:74-81.

- Lavanchy D. Evolving epidemiology of hepatitis C virus. ClinMicrobiol Infect. 2011;13(2):107-115.

- ParilloR : Long term effect of antiviral therapy on liver histology in chronic hepatitis. C. EASL; 2004.

- Pares A, Deulofeu R, Gimenez A, Caballeria L, Bruguera M, Caballeria J, Ballesta AM, RodesJ : Serum hyaluronate reflects hepatic fibrogenesis in alcoholic liver disease and is useful as a marker of fibrosis. Hepatology. 1996;24(6):1399-1403.

- Oberti F, Valsesia E, Pilette C, Rousselet MC, Bedossa P, Aube C, Gallois Y, Rifflet H, Maiga MY, Penneau-Fontbonne D, Cales P: Noninvasive diagnosis of hepatic fibrosis or cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1997:113(5):1609-1616.

- Wai CT, Greenson JK, Fontana RJ, Kalbfleisch JD, Marrero JA, Conjeevaram HS, Lok AS: A simple noninvasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38(2):518-526.

- Cadranel JF: Good clinical practice guidelines for fine needle aspiration biopsy of the liver: past, present and future. GastroenterolClin Biol. 2002;26(10):823-824.

- Guechot J, Loria A, Serfaty L, Giral P, Giboudeau J, Poupon R: Serum hyaluronan as a marker of liver fibrosis in chronic viral hepatitis C: effect of alpha-interferon therapy. J Hepatol. 1995;22(1):22-26.

- Gibson PR, Fraser JR, Brown TJ, Finch CF, Jones PA, Colman JC, Dudley FJ: Hemodynamic and liver function predictors of serum hyaluronan in alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 1992;15(6):1054-1059.

- Poupon RE, Balkau B, Guechot J, Heintzmann F: Predictive factors in ursodeoxycholic acid-treated patients with primary biliary cirrhosis: role of serum markers of connective tissue. Hepatology. 1994;19(3):635-640.

- Forns X, Ampurdanes S, Llovet JM, Aponte J, Quinto L, Martinez-Bauer E, Bruguera M, Sanchez-Tapias JM, Rodes J: Identification of chronic hepatitis C patients without hepatic fibrosis by a simple predictive model. Hepatology. 2002;36(4 Pt 1):986-992.

- Imbert-Bismut F, Ratziu V, Pieroni L, Charlotte F, Benhamou Y, Poynard T: Biochemical markers of liver fibrosis in patients with hepatitis C virus infection: a prospective study. Lancet. 2001;357(9262):1069-1075.

- Guechot J, Serfaty L, Bonnand AM, Chazouilleres O, Poupon E, Poupon R. Prognostic value of serum hyaluronan in patients with compensated HCV cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2000;32:447-52.

- Rosenberg WM, Voelker M, Thiel R, Becka M, Burt A, Schuppan D, et al. Serum markers detect the presence of liver fibrosis: A cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1704-13.

- Murawaki Y, Ikuta Y, Okamoto K, Koda M, Kawasaki H. Diagnostic value of serum markers of connective tissue turnover for predicting histological staging and grading in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:399-406.

- Skucas J: Advanced imaging of the abdomen. Springer-Verlag London limited. 2006; pp 293-418.

- Schmidt G: Ultrasound. George ThiemeVerlag. 2007;pp 231-261.

- Yajima Y, Ohta K, Narui T, Abe R, Suzuki H, Ohtsuki M: Ultrasonographical diagnosis offatty liver: significance of the liver-kidney contrast, Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine.1983;139: 43-50.

- Ishak K, Baptista A, Bianchi L, Callea F, De Groote J, GudatF.Histological grading and staging of chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol.1995;22:696-699.

- Brunt EM, Janney CG, Di Bisceglie AM, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Bacon BR. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a proposal for grading and staging the histological lesions. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(9):2467-74.

- Sanyal AJ. Review article: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatitis C-risk factors and clinical implications.Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22 (Suppl 2):48-51.

- Shepard CW, Finelli L, Alter MJ . Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:558-567.

- Lavanchy D. The global burden of hepatitis C. Liver International. 2009;29:74-81.

- Esteban JI, Sauleda S, Quer J. The changing epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection in Europe. J Hepatol. 2008;48:148-162.

- Mostafa A, Taylor SM, El-Daly M, El Hoseiny M, Bakr I, Arafa N, Thiers V, Rimlinger F, Abdel-Hamid M, Fontanet A. Is the hepatitis C virus epidemic over in Egypt? Incidence and risk factors of new hepatitis C virus infections. Liver Int. 2010;13(4):560-566.

- Westin J, Lagging LM, Wejstål R, Norkrans G, Dhillon AP: Interobserver study of liver histopathology using the Ishak score in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Liver. 1999;19:183-187.

- Bedossa P, Dargère D, Paradis V. Sampling variability of liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:1449-1457.

- Cadranel JF, Rufat P, Degos F. Practices of liver biopsy in France: results of a prospective nationwide survey. For the Group of Epidemiology of the French Association for the Study of the Liver (AFEF).Hepatology. 2000;32:477-481.

- Robert M, Sofair AN, Thomas A, Bell B, Bialek S, Corless C, Van Ness G, Huie-White S, Stabach N, Zaman A. A comparison of hepatopathologists’ and community pathologists’ review of liver biopsy specimens from patients with hepatitis C. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:335-338.

- Manning DS, Afdhal NH. Diagnosis and quantitation of fibrosis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1670-1681.

- Suzuki A, Angulo P, Lymp J, Li D, Satomura S, LindorK.Hyaluronic acid, an accurate serum marker for severe hepatic fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int. 2005;25:779-86.

- Miele L, Forgione A, La Torre G. Serum levels of hyaluronic acid and tissue metalloproteinase inhibitor-1 combined with age predict the presence of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in a pilot cohort of subjects with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Transl Res. 2009;154:194-201.

- Raszeja-Wyszomirska J, Stachowska E, Safranow K, Milkiewicz P. Factors associated with advanced liver fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic liver disease Gastroenterology. 2011;6(4):234-242.

- Esmat G, Metwally M, Zalata KR. Evaluation of serum biomarkers of fibrosis and injury in Egyptian patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2007;46:620-7.

- Sakugawa H, Nakayoshi T, Kobashigawa K, Yamashiro T et al.. Clinical usefulness of biochemical markers of liver fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(2):255-259.

- Murawaki Y, Ikuta Y, Nishimura Y. Serum markers for connective tissue turnover in patients with chronic hepatitis B and chronic hepatitis C: a comparative analysis. J Hepatol. 1995l;23:145-152.

- Murawaki Y, Ikuta Y, Koda M, Nishimura Y, Kawasaki H.Clinical significance of serum hyaluronan in patients with chronic viral liver disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;11:459-66.

- Guechot J, Poupon RE, PouponR.Serumhyaluronan as a marker of liver fibrosis. J Hepatol. 1995;22:103-6.

- Parsian H, Nouri N, Somi MH, Rahimipour A, et al. Relationship between serum hyaluronic acid level and stage of liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis.Biochemia Medica. 2009;19(2):154-65.

|