|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Case Report |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

|

|

|

Jayanth Rajagopala Reddy1, Ganesh Shenoy1, Neel Shetty1, Madhusudhan Gururajarao2, Srikanth Gadiyarami

Department of Surgical Gastroenterology1,

Minimal Access and Bariatric Surgery

Department of Plastic and Microvascular Surgery2

BGS Global Hospital, 67, BGS Health and Education City

Uttarahalli Road, Kengeri, Bangalore-560060,

Karnataka, India

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Srikanth Gadiyaram

Email: gsrikanth_31@rediffmail.com, srikanthgastro@gmail.com

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.283

48uep6bbphidvals|1347 48uep6bbphidcol2|ID 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext The colon has been a valuable conduit for esophageal reconstruction, particularly in patients with benign disease such as corrosive esophageal strictures. Colonic interposition though is associated with a higher rate of morbidity as compared to the use of a gastric interposition [1]. To reduce the rate of graft ischemia associated with colonic interposition, some centres prefer to perform additional microvessel anastomosis, referred to as supercharge (arterial connection) and super drainage (venous connection) to augment the blood supply to the transposed colon[2,3]. We report a case in which the “arterial supercharge technique” was used to prevent graft ischemia following colonic interposition.

Case report

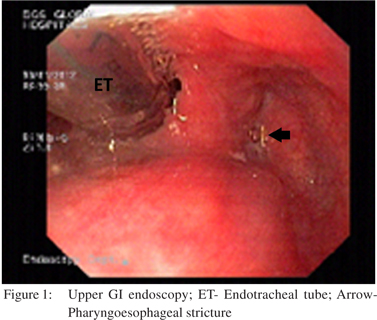

A 48 year old male presented to us with dysphagia four months following accidental ingestion of bathroom cleaning acid. Feeding jejunostomy done at the time of corrosive ingestion was in situ. On evaluation, upper GI endoscopy (UGIE) (Figure 1) and barium swallow revealed a pharyngoesophageal stricture 17 cm from the incisors which was not negotiable, a normal pyriform sinus and vallecula. Computed tomographic mesenteric angiography demonstrated normal mesenteric vascular anatomy and indirect larygoscopy showed left vocal cord paresis with compensatory medialization of the right vocal cord. He subsequently underwent intra-operative UGIE, retrograde dilatation of the pharyngo-esophageal stricture, retrosternal colonic transposition with supercharged pharyngocoloplasty, feeding jejunostomy and tracheostomy.

Surgical procedure

1. Through a curvilinear incision along the anterior border of the left sternocleidomastoid muscle the cervical esophagus below the level of pharyngoesophageal stricture was looped was looped.

Case Reports 2. Retrograde dilatation of the pharyngoesophageal stricture was done using Savary Gillard dilators (Cook Endoscopy, Salem, NC) upto 15mm via an esophagotomy below the level of the stricture and distal cervical esophagus was suture closed (Figure 2).

3. Midline laparotomy revealed scarred and contracted stomach. Right colonic segment (ascending and transverse colon) based on the ascending branch of the left colic artery was mobilized. Colonic vascularity was confirmed using serial vascular clamp test.

4. The native esophagus was left in-situ in the posterior mediastinum and a retrosternal tunnel was created. The thoracic inlet was widened by excising the medial one-third of the clavicle and the right colonic segment was transposed to the neck.

5. After noting visible marginal arterial pulsations and absence of venous congestion of the conduit end to side pharyngocolic anastomosis was done using Endo GIA TM Universal Stapler 45mm (United States Surg Corp. Norwalk, Conn.).

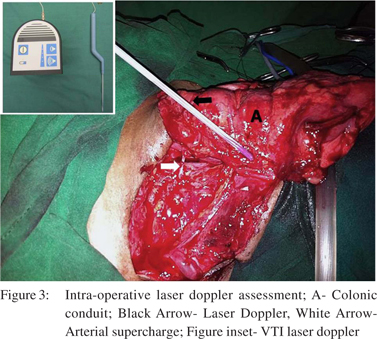

6. Following pharyngocolic anastomosis the need for supercharging arose as the transposed colonic conduit progressively became dusky and marginal arterial pulsations were not felt. VTI laser doppler (Vascular Technology Inc. Nashua, USA) assessment of the same showed subdued signals.

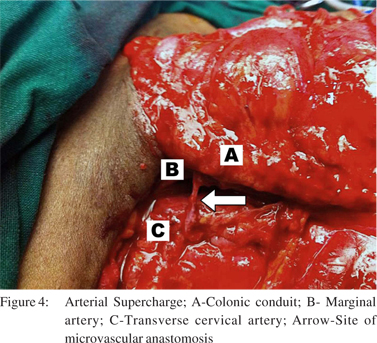

7. The neck incision was extended laterally and an arterial supercharge was established by an end to end microvascular anastomosis between the ileocolic artery (marginal artery of the conduit) and transverse cervical artery. Good signals were subsequently obtained on laser doppler assessment of the marginal artery (Figure 3 and 4).

8. Tracheostomy was done to protect the airway in view of the high level of pharyngocolic anastomosis. Post-operative course was largely uneventful except for transient swallowing dysfunction which resulted in delay in decanulation of tracheostomy. The patient is now eighteen months on follow up and is doing well.

Discussion

Following the introduction of long segment of colon for replacement or bypass of the thoracic esophagus in 1911.[4,5] it has continued to be a valuable conduit for esophageal reconstruction, particularly in patients with benign disease. There are various selection patterns of colonic grafts according to the colon segment and the pedicled vessel used; the most preferred one though is the right colonic segment ( ascending and transverse colon) based on the ascending branch of the left colic artery. The advantages of the right colon over the left colon is that it has a more reliable blood supply, provides adequate length for reconstruction, is smaller in diameter and less prone to dilatation. Despite improvements in the surgical techniques and perioperative management, colonic interposition continues to be a technically challenging surgical procedure. The common early conduit related complications following colonic transposition are graft necrosis, anastomotic leakage and stricture, each of which are greatly inûuenced by the adequacy of blood supply to the conduit. The incidence of graft necrosis following colon interposition is reported to be in the range of 0-9.4% [10].The priority for selection of the graft should therefore be based on the presence of an adequate blood supply. It should be selected after both a detailed observation of the mesenteric arterial anatomy per-operatively and assessment of the adequacy of perfusion of the graft by a serial vascular clamp test. To circumvent graft ischemia related complications some centres prefer to perform additional microvessel anastomosis, referred to as supercharge and superdrainage to augment the blood supply to the transposed colon[6,9,10]. Following O’Rourke et al 8 report of no evidence of graft necrosis or anastomotic leakage in 14 patients who underwent colon interposition with microvessel anastomosis, there has been a renewed interest in arterial augmentation techniques due to improving technical expertise of microvascular anastomosis. Fujita et al [2]showed that the incidence of anastomotic leakage following esophagocolostomy decreased significantly from 54% to 7% with the addition of supercharge and superdrainage. In addition patients who underwent microvascular augmentation in their series had both a shorter return to oral intake and post-operative hospital stay. Shirakawa et al 9 also demonstrated an anastomotic leak rate of only 7.8% in 51 patients following the addition of supercharge technique. A recent series reporting the use of supercharged colonic interposition reported a single leak in 11 patients wherein this technique was used [11]. Groups like the MD Anderson cancer centre which prefer the use of small bowel conduit for esophageal replacement also routinely practise the microvessel augmentation technique to reduce the incidence of graft loss [12]. During microvessel augmentation, anastomosis is usually performed between the proximal mesenteric vessels of the graft and the internal thoracic vessels in most cases, or in the cervical vessels such as the transverse cervical artery or the branches of the external carotid artery and the internal or external jugular vein. Although there are no reliable intraoperative tests to identify graft ischemia, reports do describe the use of a microvascular anastomosis for selected patients based on the macroscopic findings during surgery [7]. As elicited in our case, hand held laser Doppler (Vascular Technology Inc. Nashua, USA) can be very useful tool to identify impending graft ischemia per-operatively [11]. Centres routinely practicing arterial or venous augementation of colonic conduits differ in their opinion about which of the two is more important in reducing the incidence of graft ischemia and anastamotic leakage. Superdrainage of the colonic conduit is preferred by some because venous thrombosis secondary to minimal twisting of the colonic conduit is thought to be the usual precipitating ûrst event for conduit necrosis as the arterial circulation in these conduits is usually sufficient [3]. Majority of the centres routinely performing colonic interposition though, still prefer not to perform additional microvessel anastomosis [13,14]. Mine et al [7] described that the routine use of microvascular surgery during colon reconstruction was unnecessary because they did not observe any graft necrosis in 95 patients and the need for vascular augmentation was needed only in 3 patients (3.2%). Based on the above reports the effectiveness of addition of supercharge and superdrainage for prevention of anastomotic leakage and graft necrosis seems to be beneficial especially in cases where the vascular supply of the graft is not inadequate. Intra-operative use of indocyanine green perfusion study as described by Kesler et al [11] and laser doppler assessment as elicited in our case could help us in assessing the conduit blood flow thereby the need for vascular augmentation.

References

- Tom R. DeMeester. Esophageal replacement with colon interposition. Operative Techniques in Cardiac & Thoracic Surgery. 1997;2:73–86.

- Fujita H, Yamana H, Sueyoshi S, Shima I, Fujii T, Shirouzu K, et al. Impact on outcome of additional microvascular anastomosis supercharge on colon interposition for esophageal replacement: comparative and multivariate analysis. World J Surg. 1997;21:998–1003.

- H. Saeki, M. Morita, N. Harada, Egashira A, Oki E, Uchiyama H et al. Esophageal replacement by colon interposition with microvascular surgery for patients with thoracic esophageal cancer: the utility of superdrainage. Dis Esophagus. 2013;26:50–6.

- Kelling GE. Öesophagoplastik mit Hilf des Querkolon. Semin Med. 1911;38:1209–12.

- Vuillet H. De l’oesophagoplastie et des diverses modiûcations. Semin Med. 1911;31:529–30.

- Yasuda T, Shiozaki H. Surg Today. 2011;41:745–53.

- Mine S, Udagawa H, Tsutsumi K, Kinoshita Y, Ueno M, Ehara K, et al. Colon interposition after esophagectomy with extended lymphadenectomy for esophageal cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:1647–53.

- O’Rourke IC, Threlfall GN. Colonic interposition for esophageal reconstruction with special reference to microvascular reinforcement of graft circulation. Aust N Z J Surg. 1986;56:767–71.

- Shirakawa Y, Naomoto Y, Sakurama K, Nishikawa T, Nobuhisa T, Okawa T, et al. Colonic interposition and supercharge for esophageal reconstruction. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2006;391:19–23.

- Marks JL, Hofstetter WL. Esophageal reconstruction with alternative conduits. Surg Clin North Am. 2012;92:1287–97.

- Kesler KA, Pillai ST, Birdas TJ, Rieger KM, Okereke IC, Ceppa D et al. “Supercharged” Isoperistaltic Colon Interposition for Long-Segment Esophageal reconstruction. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95:1162–8.

- Blackmon SH, Correa AM, Skoracki R, Chevray PM, Kim MP, Mehran RJ et al. Supercharged pedicled jejunal interposition for esophageal replacement: a 10-year experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94:1104–11.

- Ananthakrishnan N, Kate V, Parthasarathy G. Therapeutic options for management of pharyngoesophageal corrosive strictures. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:566–75.

- Popovici Z. A new philosophy in esophageal reconstruction with colon. Thirty-years experience. Dis Esophagus. 2003;16:323–7.

|

|

|

|

|

|