|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Original Articles |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

Celiac disease, HLA DQ genotype, antiendomysial antibody, Marsh stage |

|

|

Deepak N Amarapurkar1, Vaibhav S Somani1, Apurva S Shah1, Sharada R Kankonkar2

Department of Gastroenterology1

and Tissue Typing2,

Bombay Hospital & Medical Research Center,

Mumbai, India

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Apurva S. Shah

Email: apurvashah411@gmail.com

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.279

Abstract

Background and aims: Very few human leukocyte antigen (HLA) studies have been carried out in celiac disease patients in India. The aim was to study the HLA DQ antigens in diagnosed celiac disease patients.

Methods: The cross sectional study analysed non-consecutive 34 celiac patients diagnosed as per modified ESPGHAN criteria at tertiary centre and compared with 25 controls. The HLADQ typing was carried out using Histo Spot SSO HLA DQ celiac disease kit by tissue typing department.

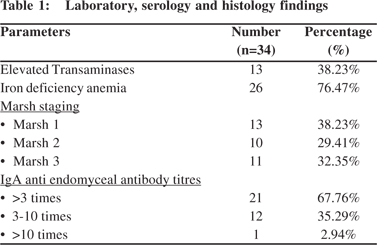

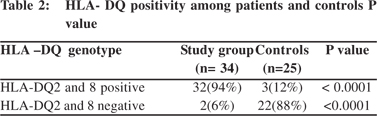

Results: Out of 34 celiac disease patients (26 females, age ± SD 38.79±15.84 years), 59% presented with typical diarrheal disease. Anemia (76%) was most common extra intestinal manifestation followed by bone pain (53%), neurological (12%) and infertility (3%). All 34 patients were IgA antiendomysial antibody positive out of which 32 patients (94%) were HLA-DQ positive (31 patients were HLA- DQ 2 and 1 was HLA-DQ 8 positive).Among HLA positive patients 13, 9 and 10 patients had modified Marsh stage 1, 2 and 3 respectively. HLA DQ 2 and DQ8 positivity among celiac patients (94%) was statistically significant as compared to controls (12%) (P< 0.0001). HLA DQ 2.5 (DQA1*0501:DQB1*0201 haplotype) and DQ 2 (DQB1*02) haplotypes were common accounting for 70% of patients followed by DQ X.5, DQ8 and DQ 2.2.

Conclusion: Celiac disease in Indian patients is predominantly associated with HLA DQ 2 and DQ 8 genotype and has high positive predictive value for diagnosis when combined with serology in symptomatic patients.

|

48uep6bbphidvals|1343 48uep6bbphidcol2|ID 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Celiac disease (CD) is defined as a chronic small intestinal immune-mediated enteropathy precipitated by exposure to dietary gluten in genetically predisposed individuals.[1]CD is now considered a relatively common disease affecting about 0.6-1% of the world’s population.[2]Its frequency in India seems to be higher in the Northern part of the country, the so-called “celiac belt”, a finding that is at least partially explained by the wheat-rice shift from the North to the South.[3] With a large population sample (n=2879), the prevalence of CD was 1.04% (1 in 96) and serological prevalence as checked by a positive anti transglutaminase antibodies (anti-tTG) was 1.44% (1 in 69) in India.[4]The diagnosis of celiac disease is made on the basis of the modified European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) criteria, including clinical manifestations, serology, histological features suggestive of celiac disease and an unequivocal response to gluten-free diet (GFD). A recent guideline promulgated by the European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) proposed that it may be possible to avoid any intestinal biopsy in children who meet the following criteria: characteristic symptoms of CD, TTG IgA levels >10× upper limit of normal (confirmed with a positive EMA in a different blood sample), and positive HLA-DQ2.[5]

Celiac disease is a strongly inheritable disease with 10% prevalence among first-degree relatives and at least 75% concordance in monozygotic twins compared with 11% in dizygotic twins.6 Studies from the Western world suggest that 30%-35% of the general population express CD associated HLA genotypes. More than 90% of CD patients express the HLADQ2.5 heterodimer encoded by the HLA-DQA1*05 (alphachain) and HLA-DQB1*02 (beta-chain) alleles, which may be inherited together on the same chromosome (cis configuration) or separately on the two homologous chromosomes (trans configuration). Most of the remaining cases are HLADQ8 (DQA1*0301 and DQB1*0302) positive.[7-10] The association between the genotype DQ2 and celiac disease has explained the high affinity of the DQ2 molecule of HLA in T- cells presenting this antigen in the intestinal mucosa, towards peptides derived from gluten.[11]

The utility of HLA testing as a screening test for CD is minimal since 30–35% of the general population in Western countries carry HLA-DQ2 and/or DQ8, but only a fraction of these individuals develop CD. The high negative predictive value of HLA typing tests, however, indicates that absence of HLA-DQ2/DQ8 can exclude the possibility or future development of CD with a certainty close to 100%.[9,12]

Clinical situations where HLA tests may be useful include[12]: A) Equivocal small-bowel histological finding (Marsh I-II) in sero negative patients, B) Evaluation of patients on a GFD in whom no testing for CD was done before GFD, C) Patients with discrepant celiac-specific serology and histology, D) Patients with suspicion of refractory CD where the original diagnosis of celiac remains in question, and E) Patients with Down’s syndrome, Turner’s syndrome.

HLA genes are lifelong stable markers and this positions this test uniquely so as to discriminate genetically CDsusceptible or not susceptible individuals before appearance of any clinical or serological signs. HLA test is increasingly considered as a solid support in the diagnostic algorithm of CD.[13]

In the present study, we aimed to study HLA DQ genotype in diagnosed celiac adults in western India.

Materials and method

The study was conducted in Gastroenterology outpatient clinics in association with the tissue typing department in a single tertiary care centre. Patients of all age groups from different states in India, presented with typical or atypical manifestation between 2004 to 2014and diagnosed as celiac disease as per modified ESPGHAN criteria, were included in this cross-sectional study. All non-consecutive patients with diagnosed celiac disease were retrospectively called for HLA genotype evaluation. 25 patients selected randomly from general population who had no symptoms or signs of CD on thorough clinical evaluation were taken as controls. In view of absence of clinical signs and symptoms, serological or small bowel biopsy was not done in controls. An informed consent statement was obtained from all of the participants in the study. The study had been approved by the Bombay Hospital Ethics Committee. History, physical examination and investigations including histology of intestinal biopsy were extracted from retrospectively maintained data. 34 celiac disease patients fulfilling the diagnostic criteria according to modified ESPGHAN criteria (2012) with a score of 4 or more had undergone blood testing for HLA DQ genotyping along with 25 controls. For HLA DQ study, 3-4 ml. of peripheral blood of each patient was collected in EDTA vacutainer and was stored at -20ºC until use. Genomic DNA was extracted using the Qiamp Mini Blood kit (Qiagen kit).

The test includes three basic steps: DNA extraction, PCR amplification, hybridization and detection. Standard protocol of hybridization was carried out using sequence specific oligonucleotides reverse array method on MR SPOT Processor from BAG Healthcare Germany using Histo Spot SSO HLA DQ celiac disease kits.

The frequency of HLA DQ2 and DQ8 were based in the frequency of the alleles - A1*05, DQB1*02, A1*0201 and B1*0302 in genotyping. We consider carrier genotype DQ2 individuals who had the alleles A1*05 and DQB1*02 in genotyping and the genotype DQ8 those who had the allele B1*0302 in PCR screening.

Results

The cross section study evaluated 34 diagnosed celiac disease patients as per modified ESPGHAN criteria. All patients were maintaining gluten free diet. Out of 34 patients, 26 were females and mean age ± SD was 38.79±15.84 year. 20 (59%) patients presented with typical diarrheal disease. Most common atypical manifestation was iron deficiency anaemia (76%) followed by elevated transaminases (38%), osteopenia (53%), neurological (12%) and infertility (3%). All 34 patients were IgA antiendomysial antibody (EMA) positive. (Table 1) Out of 34 patients, 32 patients (94%) were HLA-DQ positive (31 patients were HLA- DQ 2 and 1 was HLA-DQ 8 positive).Two patients were negative for HLA-DQ2 and DQ 8 both. HLA DQ 2.5 (DQA1*0501:DQB1*0201 haplotype) and DQ 2 (DQB1*02) haplotypes were common accounting for 70% of patients followed by DQ X.5, DQ8 and DQ 2.2. Among HLA positive patients 13(38%), 9(29%) and 10(32%) patients had Marsh stage 1, 2 and 3 respectively. Of the 25 patients taken as controls, 3 patients (12%) were positive for HLA DQ typing with haplotypes DQ2.5, DQ2 and DQ8 respectively and remaining 22 patients (88%) were negative for HLA-DQ genotyping.HLA DQ 2 and DQ 8 positivity among celiac patients (94%) was statistically significant as compared to controls (12%) (P< 0.0001) (Table 2).

Discussion

Celiac disease, originally thought to occur only rarely in childhood, is now recognised as a common condition that could be diagnosed at any age. The spectrum of clinical features of celiac disease is very wide. Only half the patients with celiac disease have typical manifestations such as chronic diarrhoea and failure to thrive, while the rest have atypical presentations such as isolated short stature, anemia resistant to therapy, osteopenia, dental enamel defects, delayed puberty and ataxia.[14,15] A typical form is characterized by minimal or absent gastrointestinal symptoms and signs with characteristic villous atrophy.[16] This form of the disease is more often recognized in older children and adults.[17]

There is continuing debate on the sole use of non-invasive tests to diagnose CD. The role of HLA DQ genotyping in celiac disease has been well documented. Very few HLA studies have been carried out in celiac disease patients in India. As we know HLA typing is used in limited clinical settings at present. The European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) recently suggested new guidelines allowing diagnosis of CD in children in the absence of small intestine biopsy in selected cases.[5] More than 90% of CD patients express the HLA-DQ2.[5] heterodimer and most of the remaining cases are HLADQ8 (DQA1*03 and DQB1*0302) positive.7-10 In the only Indian study done by Kaur et al , the HLA-DQB1*0201 was observed in all the 35 patients (100%), whereas the DQ2 heterodimer a 0â0 occurred in 97.1% of CD patients.[18]

HLA-DQ2/DQ8 genotyping is a test of high sensitivity but low specificity, because the alleles are positive in about 40% of the general population[19], although the prevalence of CD is only 1% on mass screening studies.[20] Thus, for most of the authors, the interest of the determination of the DQ2/DQ8 alleles lies in their high negative predictive value.[21–23] In a study of 354 patients [23], Pena-Quintana et al concluded that the value of this test derived from its ability to exclude the diagnosis when a negative result occurred. In a large HLA-risk genotype population, Bjork et al[24] found that 4.5% of children younger than 3 years old have an undiagnosed CD compared to none in children with HLA non risk alleles. A Finnish study of 76 doubtful cases of CD22 showed that HLA-DQ2/DQ8 typing was helpful in ruling out CD when small bowel histological findings were equivocal. Moreover, HLA-DQ2/ DQ8 typing often made it possible to rectify the diagnosis when a gluten-free diet was started before performing small-bowel biopsies. Kapitany et al[25] even concluded that diagnosis of CD based solely on histology was not always reliable and that HLA-DQ typing was important to revise diagnosis of DQ2- and DQ8-negative subjects. The value of specific antibodies for CD has already been extensively studied, and IgA EMA and tTG antibodies are presently recognized as the most efficient tests, with high sensitivity and specificity, respectively, above 90% and close to 100%. Using a test combining a sensitive parameter (HLA genotyping) with a specific test (EMA and/or tTG) appears as an attractive alternative. Clouzeau et al[26] found that 98.8% of patients with villous atrophy and increased intraepithelial T lymphocytes were also positive for serologic markers and DQ2 and/or DQ8 susceptibility alleles. This test is of high efficiency because positive likelihood ratio is high (>10), much higher than the positive likelihood ratio of serologic testing alone or HLA genotyping alone and the negative likelihood ratio is low (<0.1).

This study was carried out in patients of all age group from different states of India. Before this only one study on HLA typing in CD was done in India by Kaur et al in 2002. In our study all 34 patients were IgA antiendomysial antibody positive out of which 94% were HLA-DQ positive (31 patients were HLA- DQ 2 and 1 was HLA-DQ 8 positive). HLA DQ 2.5 (DQA1*0501: DQB1*0201 haplotype) and DQ 2 (DQB1*02) haplotypes were common accounting for 70% of patients. Of the 25 patients taken as control, 22 patients (88%) were negative for HLA DQ genotyping. These results suggest that combining serology and HLA typing results has a high positive predictive value for diagnosis of CD. Almost one third of our patients had Marsh stage 1 on small intestinal biopsy at the time of diagnosis. HLA typing along with serology confirms the diagnosis of CD in such patients. 2 patients in our study had clinical features of CD, serology positive and on small bowel biopsy histology showed partial and total villous atrophy respectively but were HLA DQ negative. These findings of variable marsh stage and HLA typing results suggest histology is not always reliable for the diagnosis of CD. On comparing a previous study done by Kapitany et al[25] where all 40 endomysial / transglutaminase antibodies positive patients carried DQ2 or DQ8, and 39 of them had severe villous atrophy (35 had subtotal and 4 had partial villous atrophy).

Only 56% of patients without endomysial or transglutaminase antibodies positivity had DQ2 or DQ8 seropositivity and relapse developed in 4 of 11 DQ2 positive but in none of 15 DQ2 and DQ8 negative patients on long-term gluten exposure .They concluded that CD diagnosis based solely on histology is not always reliable. HLA-DQ typing is important in identifying DQ2 and DQ8 negative subjects who need revision of their diagnosis, but it does not have additive diagnostic value if endomysial positivity is already known. In study done by Clouzeau et al[26] compared 2 groups; 82 children were classified in group 1 and 80 in group 2. Eighty one of 82 children in group 1 were positive for HLA and serologic testing. The other child had negative HLA and serologic testing but marked villous atrophy, and further investigation showed an allergic disease. Among the 80 children in group 2, 53 were negative for both HLA and serologic testing, 22 were positive for HLA but negative for serologic testing, 2 were negative for HLA and positive for serologic testing, and 3 patients were positive for both HLA and serologic testing. The last 3 children were shown to have an autoimmune background and had probably a latent form of CD. The association of HLA-DQ2/DQ8 and serologic markers had a sensitivity of 98.8%, a specificity of 96.2%, a positive likelihood ratio of 26.3, and a negative likelihood ratio of 0.013. Study suggested that association of positive HLA-DQ2/DQ8 and serologic testing has a high predictive value for CD. It also suggests that symptomatic children with high titers of immunoglobulin IgA tTG could be diagnosed as patients with CD without performing jejunal biopsy. In other children, HLADQ2/ DQ8 could be useful to exclude the diagnosis of CD if negative. The PCR typing of alpha and beta chains of HLA-DQ

molecules is simple and cost-effective. It is still a question whether it is necessary to examine also HLADR, DP or HLAA,- B,-C or not. DQ2 in cis is transmitted in the conserved HLAA1, Cw7, B8, DR3 haplotype in European subjects, whereas different HLA-A and -B alleles were found in coeliac disease patients in India. Also other studies suggest that only DQ molecules have additive role in the inheritance of the disease[27]. Thus, typing of HLA-DQ seems to be sufficient for clinical purposes.

The drawback of HLA typing is lack of availability. This study undoubtedly has some drawbacks. Less number of patients were evaluated for HLA association and serology or histology was not done in controls in view of less probability of celiac disease based on clinical features and routine blood investigations.

In conclusion, Celiac disease in Indian patients is predominantly associated with HLA DQ 2 and/or DQ8 genotype. Based on this, we suggest prospective study in future for role of HLA genotype for positive predictive value when combined with serology in symptomatic subjects.

References

- Ludvigsson JF, Bai JC, Biagi F et al ; BSG Coeliac Disease Guidelines Development Group; British Society of Gastroenterology. Diagnosis and management of adult coeliac disease: guidelines from the British Society of Gastroenterology. Gut. 2014;63:1210–28.

- Fasano A, Catassi C. Clinical practice. Celiac disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2419–26.

- Yachha SK, Poddar U. Celiac disease in India. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2007;26:230–7.

- Makharia GK, Verma AK, Amarchand R et al. Prevalence of celiac disease in the northern part of India: a community based study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:894–900.

- Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szabo IR et al. European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition guidelines for the diagnosis of coeliac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;54:136–60.

- Greco L, Romino R, Coto I, et al. The first large population based twin study of coeliac disease. Gut 2002;50:624–8.

- Schuppan D, Junker Y, Barisani D. Celiac disease: from pathogenesis to novel therapies. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1912–33.

- Caillat-Zucman S. Molecular mechanisms of HLA association with autoimmune diseases. Tissue Antigens. 2009;73:1–8.

- Lindfors K, Koskinen O, Kaukinen K. An update on the diagnostics of celiac disease. Int Rev Immunol. 2011;30:185–96.

- Abadie V, Sollid LM, Barreiro LB, Jabri B. Integration of genetic and immunological insights into a model of celiac disease pathogenesis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:493–525.

- Lundin KEA, Scott H, Hansen T et al. Gliadin-specific, HLA DQ (alpha1*0501, beta1*0201) restrict T cells isolated from the small intestinal mucosa of celiac disease patients. J Exp Med. 1993;178:187–96.

- Rubio-Tapia A, Hill ID, Kelly CP, Calderwood AH, Murray JA; American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guidelines: diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:656–76

- Megiorni F, Pizzuti A. HLA-DQA1 and HLA-DQB1 in Celiac disease predisposition: practical implications of the HLA molecular typing. J Biomed Sci. 2012;11:19:88.

- Makharia GK, Baba CS, Khadgawat R et al. Celiac disease: variations of presentations in adults. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2007;26:162–6.

- Cronin CC, Shanahan F. Exploring the iceberg – the spectrum of celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:518–20.

- Ludvigsson JF, Leffler DA, Bai JC et al. The Oslo definitions for coeliac disease and related terms. Gut. 2013;62:43–52.

- Catassi C, Anderson RP, Hill ID, Koletzko S, Lionetti E, Mouane N, et al. World perspective on celiac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55:494–9.

- Kaur G, Sarkar N, Bhatnagar S, et al. Pediatric celiac disease in India is associated with multiple DR3-DQ2 haplotypes. Hum Immunol. 2002;63:677–82.

- Sollid LM. Molecular basis of celiac disease. Ann Rev Immunol. 2000;18:53–81.

- Tommasini A, Not T, Kiren V, et al. Mass screening for coeliac disease using antihuman transglutaminase antibody assay. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:512–5.

- Green PH, Rostami K, Marsh MN. Diagnosis of coeliac disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19:389–400.22.

- Kaukinen K, Partanen J, Ma¨ki M, et al. HLA-DQ typing in the diagnosis of celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:695–9.

- Pena-Quintana L, Torres-Galva´n MJ, De´niz-Naranjo MC, et al. Assessment of the DQ heterodimer test in the diagnosis of celiac disease in the Canary Islands (Spain). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;37:604–8.

- Bjo¨rck S, Brundin C, Lo¨rinc E, et al. Screening detects a high proportion of celiac disease in young HLA-genotyped children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;50:49–53.

- Kapitany A, To´th L, Tumpek J, et al. Diagnostic significance of HLADQ typing in patients with previous coeliac disease diagnosis based on histology alone. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:1395–402.

- Clouzeau-Girard H, Rebouissoux L, Taupin JL et al. HLA-DQ genotyping combined with serological markers for the diagnosis of celiac disease: is intestinal biopsy still mandatory? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52:729–33

- Van Belzen MJ, Koeleman BP, Crusius JB, et al. Defining the contribution of the HLA region to cis DQ2-positive celiac disease patients. Genes Immun. 2004;5:215–20.

|

|

|

|

|

|