|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Conference Proceedings |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

Inflammatory bowel disease, severity, steroid-refractory. |

|

|

|

N Suraj Kumar,1 Rajiv Khosla,2 Govind K Makharia1

Departments of Gastroenterology &

Human Nutrition

All India Institute of Medical

Sciences, New Delhi1

Holy Family Hospital, New Delhi2

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Govind K Makharia

Email: govindmakharia@gmail.com

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.281

Abstract

Approximately 15-20% patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) suffer from a severe flare during their lifetime which required hospitalization. Intravenous corticosteroids are the first line of therapy for acute severe UC. While almost 70-80% of patients respond to corticosteroids 20% do not. Although colectomy for UC is curative, it has its problems such as increased frequency of stool and pouchitis, which led to search for colon rescue therapy. Cyclosporine and antitumor necrosis factor-alpha (anti-TNF á) have emerged as effective colon rescue therapy. While the short-term efficacy of cyclosporine in preventing colectomy is 64-86%, the longterm efficacy is not as good and almost 70% eventually require colectomy over 1-7 years. The efficacy of cyclosporine is equivalent both at a high and low doses and cyclosporine is now used most often as a low dose regime in patients with steroid refractory acute severe UC.

Furthermore, recent data suggest that the both cyclosporine and infliximab are equally effective in steroid refractory acute severe UC. Monitoring patients for adverse events and serum cyclosporine levels is mandatory. The response to both cyclosporine and infliximab is rapid and usually occurs within 4-5 days. Despite mounting evidence of its efficacy, cyclosporine remains largely underused because it requires intense monitoring for toxicity especially at higher dosage. Gastroenterologists need to be more familiar with cyclosporine for the management of steroid refractory acute severe UC.

|

48uep6bbphidvals|740 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the large intestine, caused by interplay of genetic, immunological and environmental factors.[1] The disease is characterized by a life-long chronic course interspersed with remissions and exacerbations. The course is complicated by episode(s) of acute severe colitis in approximately 15-20% of patients with UC.[2,3] Furthermore, approximately 10% of first attacks of UC are acutely severe in nature.[4] The goal of medical therapy is to avoid colectomy while preventing complications of disease, side effects of medications and mortality. In addition to institution of effective anti-inflammatory therapy in these patients, optimization of the overall supportive care is essential. Although intravenous corticosteroids are the current first-line therapy for patients with acute severe colitis, 20-30% fail to respond and require alternative therapy.[5] Surgery has been the standard of care for patients with acute severe colitis refractory to intensive regime including intravenous corticosteroids.[5]

Delay in surgery leads to higher mortality.[6]

While surgery had been the first line of management for steroid refractory acute severe colitis, the surgical procedure i.e. restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch–anal anastomosis (IPAA) has its disadvantages. It is a multi-step surgery (usually three stages), leads to higher postoperative stool frequency and complications such as pouchitis, pelvic sepsis and pouch failure. Reduced fertility associated with IPAA is also a major concern for women who have not completed their families.[7] Hence emerged a need for alternative management of steroid-refractory severe UC. Alternative therapies such as calcineurin inhibitor, cyclosporine (CsA) and TNF-á antagonists, mainly infliximab (IFX) have now emerged as colon rescue therapy for patients with steroid refractory acute severe UC. In this review we summarize the evidence for short-term and long-tem efficacy of CsA in acute severe UC, its side effects, monitoring schedule and best practice guidelines.

CsA was first isolated in 1970 by Borel et al from a fungus named Tolypocladium inflatum Gams.[8] Its potent immunosuppressive effects revolutionized the immunosuppression required for organ transplantation. CsA is now an alternative treatment option for patients with steroid refractory acute severe UC who previously could resort only to surgery.[9]

Mechanism of action of CsA

Triggering an immune response involves a cascade of events such as: T cell antigen presentation classically by macrophages, antigen processing, and programming of T- and B-lymphocytes. CsA inhibits the early events in T-helper cell activation which normally lead to recruitment and expansion of cytotoxic T cells, and activation of B-cell clones which eventually secrete specific immunoglobulins. Amongst this complex series of events, one prominent target for the action of CsA is the inhibition of interleukin-2 (IL-2) synthesis by activated T-helper lymphocytes; which ultimately leads to clonal expansion of Tlymphocytes. CsA also inhibits expression of IL-2 receptors on cytotoxic T lymphocyte precursors. Additionally CsA also inhibits generation of other cytokines such as B-cell activating factors and interferon gamma. The net effect of CsA is a reduction of both cell- and antibody-mediated immune responses.[10]

Normally cyclophilin, a cytoplasmic receptor protein, binds to calcineurin, a calcium and calmodulin-dependent phosphatase, leading to dephophorylation of nuclear factor for activated T-cells (NFAT) which further leads to nuclear translocation of cytoplasmic NFAT and transactivation of IL-2 and other lymphokine genes. CsA is a lipophilic cyclic peptide that binds to cyclophilin with high affinity. The CsA–cyclophilin complex specifically and competitively inhibits calcineurin. This prevents translocation of NFAT transcription factor ultimately blocking gene transcription and production of IL-2 and other cytokines.[11]

Short-term efficacy of CsA in acute severe UC

The first evidence of efficacy of CsA in the management of steroid refractory acute severe UC was suggested by successful open-label trials in 1980s and early 1990s.[12,13] The initial success of CsA in steroid refractory acute severe colitis led to a landmark randomized controlled trial in 1994 by Lichtiger et al. They enrolled 20 patients with severe UC unresponsive to at least 7 days of intravenous corticosteroids and randomized them to receive either CsA 4 mg/kg/day by continuous intravenous infusion or placebo.[9] Treatment was continued for 14 days and if there was no clinical response, patients in CsA arm underwent colectomy and patients in the placebo arm were offered open label CsA. Although the number of patients was small, the results of this study were impressive and highly significant. Nine of 11 patients (82%) treated with CsA had a response within a mean seven days, as compared with none of the 9 patients who received placebo (p <0.001). The mean clinicalactivity score fell from 13 to 6 in the CsA group, as compared with a decrease from 14 to 13 in the placebo group. All five patients in the placebo group who later received cyclosporine therapy showed a favourable response.[9]

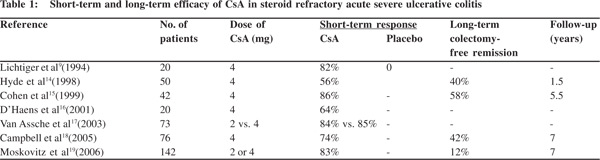

In a retrospective analysis of 84 patients out of 216 acute severe colitis cases unresponsive to intravenous corticosteroids, 34 (40%) proceeded directly to colectomy while 50 received 4 mg/kg CsA by continuous slow infusion. Induction of remission was achieved with intravenous CsA in 28/50 (56%) patients who subsequently were put on 5 mg/kg oral CsA. However, 8/28 (29%) who initially responded relapsed after discharge and had to undergo colectomy. The short-term efficacy of CsA in steroid refractory acute severe colitis was 56% but fell to 40% over intermediate term over a mean followup of 19 months.[14] There is growing evidence and renewed interest in CsA for acute severe UC refractory to corticosteroids. Many other uncontrolled, small studies have examined the performance of intravenous CsA in steroid refractory UC patients (Table 1). The overall short-term efficacy of CsA in avoiding colectomy in patients with steroid refractory acute severe UC varies from 64-86%.[9,14-19]

Long-term efficacy of CsA in prevention of colectomy in steroid refractory acute severe UC While short-term efficacy of CsA is impressive, its long-term efficacy is an important issue. The long-term colectomy rate in such patients depends on the continuation of drugs to maintain disease remission. Therefore continuation of an effective maintenance therapy is the key. Since CsA is generally not continued for long in UC patients, its long-term efficacy in terms of colectomy rate depends on the continuation of maintenance therapy with thiopurines, which are known for maintaining remission in UC.

In a cohort of 42 acute severe UC patients treated with intravenous CsA and on long-term follow-up, colectomy could be avoided in 67% over one year and 58% at 5.5 years. If only the patients who initially responded to CsA were included in the analysis, the probability of avoiding colectomy was 80% at one year and 70% at 5.5 years.[15] In a retrospective long-term follow-up study from Oxford, 76 patients with acute UC were treated with intravenous CsA. 42% could avoid colectomy up till 7 years.[18] A recent study from the same unit in Oxford showed that incomplete CsA responders within 1 week after admission had a 50% chance of requiring colectomy within a year and 70% within 5 years.[20]

Investigators from Leuven predicted that 55% CsA treated patients would avoid colectomy over 3 years. When this cohort was followed up the probability of avoiding colectomy after successful intravenous CsA was 63% at one year, 41% at four years, 16% at six years and 12% at seven years.[19] In summary, while the short-term efficacy of intravenous CsA in preventing colectomy in patients with steroid refractory UC varies between 66-86%, its long-term efficacy is less encouraging. Colectomy rate remains high reaching up to 58–88% at seven years.[18,19]

Efficacy of low dose versus high dose CsA in acute severe colitis

At least a part of the toxicity of CsA part is related to its dose. Van Assche et al in a single centre randomized double-blind controlled trial randomly assigned 73 patients with severe UC (defined by a Lichtiger Clinical Activity Index of 10 or more) to high dose (4 mg/kg) (n=38) and low-dose (2 mg/kg) (n=35) intravenous CsA on day 1, continued till day 8. Responders were put on oral CsA at a dose of 8 mg/kg. Thirty-two of 38 patients (84%) in the high-dose group and 30 of 35 patients (85%) in the low-dose group reached the primary end-point (clinical response as defined by a score of <10 at day 8 with a drop of more than or equal to 3 points as compared to baseline).There was no significant difference in the secondary end-points including short-term colectomy rates and median response time.

Interestingly, drug dosage was adjusted according to blood levels. On days 0–1, patients received 4 or 2 mg/kg, respectively and from day 2 to day 8, blood levels were strictly controlled between 150 and 250 ng/mL in the low-dose group and 250 and 350 ng/mL in the high-dose group (random levels during continuous CsA infusion). In fact, the mean daily dose over the 8 days was 1.82 ± 0.32 mg/kg in the low-dose and 2.65 ± 0.47 mg/kg in the high-dose groups. While a suitable target level of CsA for inducing remission in acute severe colitis is unknown, evidence suggests that a level between 150–250 ng/ mL of CsA can achieve high response rates. Most clinicians now use CsA at a low-dose in acute severe colitis.[17]

Efficacy of CsA alone or in combination with corticosteroids

Another relevant question is whether CsA is effective for primary therapy, without using corticosteroids for controlling acute severe UC. D’Haens et al from Belgium addressed this issue in a double-blind controlled trial. They randomized 29 patients with acute severe colitis to receive either CsA 4 mg/kg or 40 mg of intravenous methylprednisolone (40 mg/day). Nine of the 14 patients (64%) who received intravenous CsA compared with eight of the 15 patients (53%) who received methylprednisolone achieved a favourable clinical response on days 7 and 8. Several patients failing monotherapy subsequently responded to combination therapy.[16] A more important question therefore is whether CsA plus corticosteroids is more effective than CsA alone. This issue has been addressed in one small study from Italy where Svanoni et al compared the efficacy of CsA monotherapy (4 mg/kg) and CsA in combination with intravenous prednisolone (1 mg/kg) in 30 patients. Sixty-seven percent responded to monotherapy, whereas 93% responded to the combination.[21]

Overall, it seems that monotherapy is effective, but combination therapy probably salvages more patients. The added advantage seems to be at expense of greater toxicity though data available in the literature is insufficient to prove it.[22]

How fast the response appears

CsA is a rapid acting drug and response typically occurs within 4–7 days of starting therapy. Such rapid action of CsA is of considerable benefit to patients with acute severe colitis. If there is no response to CsA, a decision in favor of colectomy can be made within the first week itself. After discontinuation, CsA undergoes rapid systemic clearance reversing calcineurin inhibition.[22,23]

Factors which predict response to CsA

In a study from France on 135 acute severe colitis patients receiving CsA, Cacheux et al[24] reported three parameters including temperature >37.5oC, pulse rate >90/min and CRP level >45 predictive of colectomy. Rates of colectomy at 6 months were 22%, 47%, 55% and 90% when 0, 1, 2 and 3 of these factors were present, respectively. Severe endoscopic erosions were an independent predictor of colectomy. In the 118 patients who underwent colonoscopy, the presence of severe endoscopic lesions was an independent predictive factor of colectomy. In another study from Cedar Senai Medical Center, USA, a high percentage of band neutrophils (bands) at admission were found to be a significant predictor of response to CsA.[25] Saito et al from Japan identified four independent predictors of response including age at hospitalization, platelet count on the first day, Lichtiger score on the third day and total protein on the third day minus total protein on the first day.[26] In summary, clinical, laboratory and endoscopic features help predict response to therapy. These predictors should be examined in such patients to enable a timely decision for alternative therapies.

Adverse effects of CsA

Nearly one-third to half of patients receiving CsA, report minor adverse events such as tremors, paraesthesia, malaise, headache and abnormal liver function. Gum hypertrophy and hirsutism are common, troublesome problems of long-term use, but rarely an issue with short-term therapy.[18] Anaphylaxis due to intravenous CsA can occur uncommonly.[14,27]

One of the most important side effects of CsA is renal failure. While mild reversible renal impairment is common but serious renal failure can also occur. Acute nephrotoxicity is because of dose-dependent vasoconstriction of afferent and efferent glomerular arterioles, resulting in reduced renal blood flow and fall in glomerular filtration rate.[28] Long-term CsA use may cause chronic nephrotoxicity resulting from obliterative arteriopathy, ischemic collapse or scarring of glomeruli, vacuolization of tubules, focal tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis. Even tubular damage can occur with CsA use which can lead to hyperuricaemia, metabolic acidosis, hypophosphatemia and hypomagnesemia. Renal biopsies of 192 patients on CsA for non-renal autoimmune disease showed evidence of nephropathy in 21% patients.[29]

CsA can precipitate seizures and other neurological adverse effects. The mechanism of CsA-induced neurotoxicity is unknown, but some of the proposed mechanisms reported in the literature include high blood levels of CsA, direct toxic effect of CsA on the blood brain barrier, hypomagnesemia and hypertension. Furthermore, in liver transplant recipients, hypocholesterolemia was also found to be a risk factor for CsA induced neurotoxicity.[30] It is proposed that low cholesterol levels increase the amount of CsA bound to low-density lipoproteins (LDL), resulting in increased CsA delivery to astrocytes which bear LDL receptors.[31] The profound immunosuppressive effects of CsA result in a significant risk of infections. The risk of immunosuppression is dose dependent and compounded by treatment with corticosteroids, thiopurines and the general condition of the patient. Profound immunosuppression predisposes the patients to infections including opportunistic pathogens.[22]

Guidance for CsA use in acute severe colitis

Baseline studies and contraindications

Given the high propensity for nephrotoxicity renal function should be thoroughly assessed before instituting CsA. This is even more important in patients with advanced age (>50 year).

Hypertension must be adequately controlled. Persistent fevers including low-grade should be promptly investigated in severe UC patients on high-dose steroids.

Both hypocholesterolemia (<120 mg/dl) and hypomagnesemia (<1.5 mg/dl) increase the risk of seizures in patients receiving CsA.[32] Hypomagnesemia should be treated with parenteral magnesium because oral magnesium is likely to exacerbate diarrhea. Hypocholesterolemia can be treated with either a cholesterol-rich diet or with parenteral intralipids. The correction of hypocholesterolemia can take several days, often up to 1-2 weeks. Hence serum cholesterol should be checked early in the course of acute severe colitis. Patients with a history of seizure must be on anti-seizure medications. All patients should be screened for signs of infection. Patients with history of treatment non-compliance and/or poor follow-up should be counseled on the importance of regular follow-up while on CsA. A past history of malignancy within last 5 years other than a treated basal or squamous call carcinoma is a relative contraindication. A detailed drug history should be elicited as CsA is known for several drug interactions.[33]

Drug interactions

CsA is known for drug interactions with many drugs especially antifungals, calcium channel blockers and omeprazole, which can increase blood levels of CsA. Drug interaction with carbamazepine and phenytoin reduces CsA blood levels. Sulphasalazine increases the risk of nephrotoxicity, and nifedipine of gum hypertrophy.[22]

Dosing, schedule and administration of CsA in steroid refractory acute severe UC

Initial intravenous dosing

As discussed earlier, the efficacy of CsA in steroid refractory acute severe UC both at high and low dose is almost similar. Most clinicians and clinical scientists now use CsA at a dose of 2 mg/kg per day as continuous intravenous infusion for 1 week. CsA should be given as continuous infusion in 5% dextrose or normal saline and should preferably be infused through glass bottles because it binds with plastic. It is critical to maintain CsA blood levels at 150-250 ng/mL. If the patient has been on 6-MP or azathioprine, these should be withdrawn temporarily before starting CsA in order to avoid high dose triple drug immunosuppressive therapy. These drugs can be re-introduced after the patient is discharged.[33]

Switching to oral CsA

In patients who respond to at least 7 days of intravenous CsA, the drug is changed to oral formulation with dose twice that of intravenous dose in two divided doses. On the day of switch intravenous CsA is stopped at 8 pm and CsA levels are measured at 8 am prior to first oral dose. Patients should be followed every week for the first month and then biweekly over the second month and then at least once every month. At each follow-up visit patient’s clinical status, drug-related side effects, routine blood counts, serum magnesium and blood CsA levels should be monitored.[33]

How long to continue oral CsA as a bridge to immunomodulators?

A response or remission induced with intravenous CsA in patients with IBD typically requires continuation of therapy with oral CsA for a few months usually 3 to 6 months, along with a tapering dose of corticosteroids and initiation of AZA or 6-MP therapy. AZA or 6-MP should be continued as maintenance therapy.[32]

Monitoring

Patients should be enquired daily for symptoms of CsA toxicity such as headache, nausea or paresthesia. Serum potassium and magnesium should be monitored daily.[32] During initial intravenous infusion the physician should be watchful for anaphylactic reaction (hypertension, wheezing, laryngeal spasm). Blood CsA level should be checked every 2 days starting at 48 hours after initiation of CsA, aiming a trough level of 150-250 ng/ml. The dose of CsA is reduced by 25% in conditions where serum creatinine increases by >30% over baseline, serum liver enzymes rise to double, diastolic blood pressure exceeds 90 mmHg or systolic blood pressure exceeds 150 mmHg despite antihypertensive treatment.[33]

Prophylaxis against Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia Evidence suggests that institution of prophylaxis for Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) in renal transplant patients on CsA reduces PCP infection. This led some clinicians to suggest PCP prophylaxis even for acute severe colitis patients who are on CsA. However, PCP infection in acute severe colitis treated with CsA is very uncommon and thus routine PCP prophylaxis is not recommended. Sandborn[34] in a comprehensive review of all CsA trials in inflammatory bowel disease conducted till 1995 examined 321 patients and PCP infection was reported in only one (0.3%) in comparison to 6% in renal transplant patients receiving CsA. It is thus appropriate to recommend PCP prophylaxis in those patients who are likely to receive a prolonged triple immunosuppressive therapy including corticosteroids, azathioprine and cyclosporin.

CsA or IFX in steroid refractory acute severe UC?

Both CsA and IFX have excellent efficacy in controlling acute severe colitis. But clinicians often are in a dilemma of which one to prefer. The results of a recent European multi-centric randomized controlled trial comparing efficacy of CsA and IFX in acute severe colitis have clarified this issue. Laharie et al36 randomly assigned 115 patients who had failed intravenous corticosteroid treatment and had a Lichtiger score of >10 at the time of enrollment to receive either CsA (2 mg/kg per day; n = 57) or a single infusion of infliximab (5 mg/kg; n = 56) in conjunction with intravenous corticosteroids. Patients who responded by day 7 were put on either oral CsA (4 mg/kg in two divided doses until day 98; CsA group) or received additional doses of infliximab (5 mg/kg at week 2 and 6; infliximab group). All responders were transitioned to oral corticosteroids and initiated on azathioprine (2–2.5 mg/kg day).

The primary end-point of the study was treatment failure, defined as any of the following: absence of clinical response by day 7, relapse between day 7 and day 98, inability to achieve steroid-free clinical remission, a serious adverse event, colectomy or death. Secondary outcomes were clinical response at day 7, mucosal healing and colectomy-free survival. Treatment failure rates were similar (60% in the CsA group and 54% in the infliximab group, p=0.52). The treatment groups also had similar levels of clinical response at day 7 (86% in the CsA group and 84% in the IFX group, p=0.76), median time to response (5 days in CsA group and 4 days in the IFX group, p=0.12), rates of mucosal healing (47% CsA group and 45% IFX group, p=0.85) and colectomy rate (17% CsA group and 21% IFX group, p=0.60). The adverse events were slightly greater in the IFX group (25%) compared with the CsA group (16%).[35]

This study has provided the first prospective comparison between CsA and IFX and the results suggest that both medications are well tolerated and are equally efficacious in treating acute severe colitis. Although the choice of therapy needs to be tailored to individual patient preference, additional factors also need to be taken into consideration. First, previous history of thiopurine use and ability to tolerate thiopurines needs to be ascertained; patients who are unable to tolerate thiopurines are not eligible for CsA, as CsA serves as a bridge to long-term maintenance with thiopurines. Second, patients who are treatment naïve for thiopurines have better long-term outcomes with CsA compared with thiopurine ‘veterans’; the latter group might be better suited for infliximab treatment.[23]

Despite efficacy CsA has not been used widely Despite proven short-term efficacy of CsA it has not been widely adopted in many countries for the management of acute severe colitis. The possible reasons for the underuse of CsA include risk of toxicity and even mortality, need for continuous intravenous infusion and requirement for regular blood level monitoring. Furthermore, there is greater experience with IFX given its wider indications in IBD and relatively less complicated administration.

Switching between CsA and IFX

While both CsA and IFX have an efficacy of almost 60-80% in steroid refractory acute severe colitis, there still remain patients unresponsive to both. Most clinician resort to surgery in such patients rather than trying another class of drugs. In this situation, a relevant question is whether one should switch to IFX if CsA has failed or vice versa. One must realize that the strategy of switching between CsA and infliximab involves a significant risk of continuing with a severely inflamed colon. Therefore it is imperative to weigh risks between surgery and continuing medical rescue therapy.[36]

Conclusions

In summary, while the short-term efficacy of intravenous CsA in preventing colectomy in steroid refractory acute severe UC approaches 64-86%, the long-term results are less encouraging. Colectomy rate remains high in latter and reaches up to 58– 88% at 7 years. CsA demonstrates similar efficacy both at a high and low doses and is used most often as a low dose regime. The efficacy of CsA and IFX is almost similar for preventing colectomy in steroid refractory acute severe UC. Monitoring of adverse effects and CsA blood levels is mandatory. Despite convincing data CsA use remains restricted to large referral centers owing to concerns regarding its safety, the tedious continuous intravenous infusion, the need for frequent monitoring of laboratory parameters such as renal function, serum electrolytes and cholesterol levels and monitoring of drug levels. There is a need for greater awareness among gastroenterologists regarding use of CsA in the management of steroid refractory acute severe UC.

References

- Stange EF, Travis SP, Vermeire S, Reinisch W, Geboes K, Barakauskiene A, et al. European evidence-based Consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis: Definitions and diagnosis. J Crohns Colitis. 2008;2:1–23.

- Travis SP, Farrant JM, Ricketts C, Nolan DJ, Mortensen NM, Kettlewell MG, et al. Predicting outcome in severe ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1996;38:905–10.

- Edwards FC and Truelove SC. The course and prognosis of ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1963;4:299–315.

- Solberg IC, Lygren I, Jahnsen J, Aadland E, Hoie O, Cvancarova M, et al. Clinical course during the first 10 years of ulcerative colitis: results from a population-based inception cohort (IBSEN Study). Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:431–40.

- Moss AC and Peppercorn MA. Steroid-refractory severe ulcerative colitis: what are the available treatment options? Drugs. 2008;68:1157–67.

- Pal S, Sahni P, Pande GK, Acharya SK, Chattopadhyay TK. Outcome following emergency surgery for refractory severe ulcerative colitis in a tertiary care centre in India. BMC Gastroenterol. 2005;5:39.

- Ording Olsen K, Juul S, Berndtsson I, Oresland T, Laurberg S. Ulcerative colitis: female fecundity before diagnosis, during disease, and after surgery compared with a population sample. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:15–9.

- Borel JF, Feurer C, Gubler HU, Stahelin H. Biological effects of cyclosporin A: a new antilymphocytic agent. Agents Actions. 1976;6:468–75.

- Lichtiger S, Present DH, Kornbluth A, Gelernt I, Bauer J, Galler G, et al. Cyclosporine in severe ulcerative colitis refractory to steroid therapy. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1841–5.

- Hodgson HJ. Cyclosporin in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1991;5:343–50.

- Krensky AM, Bennett WM, Vincenti F. Immunosuppressants, tolerogens and immunostimulants. Chapter 35. In: Goodman and Gilman’s The pharmacological basis of therapeutics, 12th ed. McGraw Hill Professional. p. 1009–11.

- Gupta S, Keshavarzian A, Hodgson HJ. Cyclosporin in ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 1984;2:1277–8.

- Lichtiger S and Present DH. Preliminary report: cyclosporin in treatment of severe active ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 1990;336:16–9.

- Hyde GM, Thillainayagam AV, Jewell DP. Intravenous cyclosporin as rescue therapy in severe ulcerative colitis: time for a reappraisal? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;10:411–3.

- Cohen RD, Stein R and Hanauer SB. Intravenous cyclosporin in ulcerative colitis: a five-year experience. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1587–92.

- D’Haens G, Lemmens L, Geboes K, Vandeputte L, Van Acker F, Mortelmans L, et al. Intravenous cyclosporine versus intravenous corticosteroids as single therapy for severe attacks of ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1323–9.

- Van Assche G, D’Haens G, Noman M, Vermeire S, Hiele M, Asnong K, et al. Randomized, double-blind comparison of 4 mg/kg versus 2 mg/kg intravenous cyclosporine in severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1025–31.

- Campbell S, Travis S, Jewell D. Ciclosporin use in acute ulcerative colitis: a long-term experience. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17:79–84.

- Moskovitz DN, Van Assche G, Maenhout B, Arts J, Ferrante M, Vermeire S, et al. Incidence of colectomy during long-term followup after cyclosporine-induced remission of severe ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:760–5.

- Bojic D, Radojicic Z, Nedeljkovic-Protic M, Al-Ali M, Jewell DP and Travis SP. Long-term outcome after admission for acute severe ulcerative colitis in Oxford: the 1992-1993 cohort. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:823–8.

- Svanoni F, Bonassi U, Bagnolo F, et al. Effectiveness of cyclosporine A (CsA) in the treatment of active refractory ulcerative colitis (UC). Gastroenterology. 1998;114:A1096.

- Durai D and Hawthorne AB. Review article: how and when to use ciclosporin in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:907–16.

- Kaur M and Targan SR. Ulcerative colitis: steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis-ciclosporin or infliximab? Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:8–9.

- Cacheux W, Seksik P, Lemann M, Marteau P, Nion-Larmurier I, Afchain P, et al. Predictive factors of response to cyclosporine in steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:637–42.

- Rowe FA, Walker JH, Karp LC, Vasiliauskas EA, Plevy SE and Targan SR. Factors predictive of response to cyclosporin treatment for severe, steroid-resistant ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2000–8.

- Saito K, Katsuno T, Nakagawa T, Saito M, Sazuka S, Sato T, et al. Predictive factors of response to intravenous ciclosporin in severe ulcerative colitis: the development of a novel prediction formula. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:744–54.

- Haslam N, Hearing SD, Probert CS. Audit of cyclosporin use in inflammatory bowel disease: limited benefits, numerous sideeffects. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12:657–60.

- Lanese DM and Conger JD. Effects of endothelin receptor antagonist on cyclosporine-induced vasoconstriction in isolated rat renal arterioles. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:2144–9.

- Feutren G and Mihatsch MJ. Risk factors for cyclosporineinduced nephropathy in patients with autoimmune diseases. International Kidney Biopsy Registry of Cyclosporine in Autoimmune Diseases. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1654–60.

- de Groen PC, Aksamit AJ, Rakela J, Forbes GS, Krom RA. Central nervous system toxicity after liver transplantation. The role of cyclosporine and cholesterol. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:861–6.

- de Groen PC. Cyclosporine, low-density lipoprotein, cholesterol. Mayo Clin Proc. 1988;63:1012–21.

- Dunckley P and Jewell D. Management of acute severe colitis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;17:89–103.

- Kornbluth A, Present DH, Lichtiger S and Hanauer S. Cyclosporin for severe ulcerative colitis: a user’s guide. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1424–8.

- Sandborn WJ. A critical review of cyclosporine in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases.1995;1:48–63.

- Laharie D, Bourreille A, Branche J, Allez M, Bouhnik Y, Filippi J, et al. Ciclosporin versus infliximab in patients with severe ulcerative colitis refractory to intravenous steroids: a parallel, open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380:1909–15.

- Maser EA, Deconda D, Lichtiger S, Ullman T, Present DH, Kornbluth A. Cyclosporine and infliximab as rescue therapy for each other in patients with steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1112–6.

|

|

|

|

|

|