|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Case Report |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

|

|

|

Sijo K John, Josmy Joseph

Department of Surgery,

MOSC Medical College,

Kolenchery, Ernakulam, Kerala - 682311, India.

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Sijo K John

Email: drsijokjohn@yahoo.com

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.2012.58

48uep6bbphidvals|543 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Myiasis has been reported all around the world, but is more common in the tropical region. Anal myiasis is rare and there are only a handful of reports in the literature.[1–4] We present a case of ‘myiasis-in-ano’ where the patient had no obvious preexisting anal pathology.

Case report

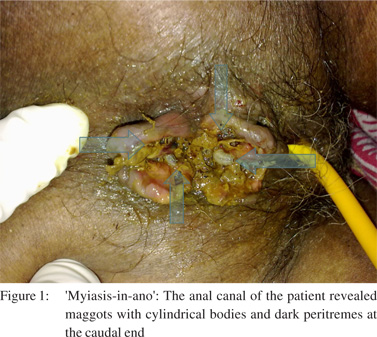

A 72-year-old lady presented to our Emergency Department, referred by a general practitioner for further management of a cerebrovascular accident which occurred two weeks ago. History revealed that she was bedridden for the last two weeks and was put under the care of a home nurse. Examination revealed a conscious and oriented lady with poor hygiene, adequate nourishment and mild pallor. Neurological examination revealed right hemiplegia. A surgical consultation was sought on finding blood stained faecal soiling on her clothing. Inspection of the perianal region revealed an anal canal infested with maggots and active oozing of blood from multiple linear fissures (Figure 1). There was no growth or ulcer in the region. On digital rectal examination, there was no sphincter spasm or obvious rectal pathology. External genitalia and urethral opening were normal. A flexible sigmoidoscopy revealed normal rectum and sigmoid, with no maggots within the lower intestinal tract.

The patient was treated with local instillation of mineral turpentine (MT), followed by manual removal of maggots. A few maggots were seen migrating into the rectum and vagina following MT application. A cleansing enema instituted immediately following MT application helped expel around 2– 3 maggots. The external genitalia were protected by using a tampon prior to application of MT. She was given oral antibiotics to prevent secondary infection. Two of the extracted maggots were sent to a medical entomologist and were identified as larvae of Chrysomya bezziana. After six days of treatment, there were no further maggots visible and the fissures were healing. She was discharged on the 10th day and referred for rehabilitation, with advice to care givers on hygiene and good nutrition.

Discussion

Myiasis has been reported from all around the world, but is more common in the tropical region. The incidence and the site of invasion are dependent on the health of the host, hygiene, sanitation and other environmental factors. Myiasis usually occurs at sites of natural (orifices) and unnatural (wounds) openings in the body. The commonest site of myiasis is the foot.[5] Anal myiasis is rare and there are only a handful of reported cases; most in pre-existing carcinomatous ulcers, condyloma accuminata, fistula-in-ano and gangrenous haemorrhoids.

The term myiasis was coined by Hope[6] in 1840 to refer to diseases of humans originating specifically due to dipterous larvae. In 1965, Zumpt[7] defined myiasis as ‘the infestation of live vertebrate animals with dipterous larvae, which, at least for a certain period, feed on the host’s dead or living tissue, liquid body substances or ingested food’. It may be deleterious when the obligate and primary species attack the host’s healthy tissues or it may be benign, as when secondary species attack only the diseased and dead tissue. Controlled myiasis has been used as scavengers to clean up necrotic material in wounds in olden days and ‘maggot therapy’[8] has evoked interest in the recent past as well.

MT and low aromatic white spirits, the main ingredient of MT, are effective in killing the Chrysomya larvae.[9] Commercially available MT is being used widely in hospitals of the tropical region for treatment of myiasis. MT is cheap and does not have any reported adverse effects; however, there are potential risks in using commercially available MT. Other topical agents used include chloroform, ether, ethanol, dextrose and oil. Surgical debridement is usually not necessary.[10] Ivermectin has been reported to be effective in treating wound myiasis, but it is expensive and is not available in most tropical countries.

References

Discussion

Myiasis has been reported from all around the world, but is more common in the tropical region. The incidence and the site of invasion are dependent on the health of the host, hygiene, sanitation and other environmental factors. Myiasis usually occurs at sites of natural (orifices) and unnatural (wounds) openings in the body. The commonest site of myiasis is the foot.[5] Anal myiasis is rare and there are only a handful of reported cases; most in pre-existing carcinomatous ulcers, condyloma accuminata, fistula-in-ano and gangrenous haemorrhoids.

The term myiasis was coined by Hope[6] in 1840 to refer to diseases of humans originating specifically due to dipterous larvae. In 1965, Zumpt[7] defined myiasis as ‘the infestation of live vertebrate animals with dipterous larvae, which, at least for a certain period, feed on the host’s dead or living tissue, liquid body substances or ingested food’. It may be deleterious when the obligate and primary species attack the host’s healthy tissues or it may be benign, as when secondary species attack only the diseased and dead tissue. Controlled myiasis has been used as scavengers to clean up necrotic material in wounds in olden days and ‘maggot therapy’[8] has evoked interest in the recent past as well.

MT and low aromatic white spirits, the main ingredient of MT, are effective in killing the Chrysomya larvae.[9] Commercially available MT is being used widely in hospitals of the tropical region for treatment of myiasis. MT is cheap and does not have any reported adverse effects; however, there are potential risks in using commercially available MT. Other topical agents used include chloroform, ether, ethanol, dextrose and oil. Surgical debridement is usually not necessary.[10] Ivermectin has been reported to be effective in treating wound myiasis, but it is expensive and is not available in most tropical countries.

References

- Gupta PJ. Human myiasis in anal carcinomatous ulcer – a case report. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2009;13:473–4.

- Gupta PJ. Myiasis: a perianal wound infection caused by fly larvae in gangrenous hemorrhoid. Tech Coloproctol. 2006;10:254–5.

- da Silva AL, Santos Ide O. Ano-rectal myiasis. Rev Bras Med. 1965;22:273–5.

- Calzaretto J, Fuenzalida E, Litrenta SR. Anal condyloma acuminata with myiasis. Prensa Med Argent. 1965;52:2282–3.

- Lukin LG. Human cutaneous myiasis in Brisbane: a prospective study. Med J Aust. 1989;150:237–40.

- Hope FW. On insects and their larvae occasionally found in the human body. Trans R Soc Entomol. 1840;2:256–71.

- Zumpt F. Myiasis in Man and Animals in the Old World. London: Butterworths, 1965.p.89–102, 267.

- Sherman RA, Hall MJ, Thomas S. Medicinal maggots: an ancient remedy for some contemporary afflictions. Annu Rev Entomol. 2000;45:55–81.

- Kumarasinghe SP, Karunaweera ND, Ihalamulla RL, Arambewela LS, Dissanayake RD. Larvicidal effects of mineral turpentine, low aromatic white spirits, aqueous extracts of Cassia alata, and aqueous extracts, ethanolic extracts and essential oil of betel leaf (Piper betle) on Chrysomya megacephala. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:877–80.

- Kumarasinghe SP, Karunaweera ND, Ihalamulla RL. A study of cutaneous myiasis in Sri Lanka. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:689–94.

|

|

|

|

|

|