|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Original Articles |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

capsulated urea breath test, 14C-UBT, 14C-urea, 14C-urea breath test, Helicobacter pylori |

|

|

Chander M Pathak,1 Balwinder Kaur,1 Deepak K Bhasin,2 Bhagwant R Mittal,3 Sarika Sharma,3 Krishan L Khanduja,1 Lalit Aggarwal,4 Surinder S Rana2

Departments of Biophysics,1

Gastroenterology2 and

Nuclear Medicine,3

Post Graduate Institute of Medical

Education and Research, Chandigarh;

Department of Surgery,4

Lady Harding Medical College,

New Delhi,

India

Corresponding Author:

Dr. CM Pathak

Email:chander_pathak@rediffmail.com

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.2012.29

Abstract

Background: 14C-urea breath test (14C-UBT) is employed as a ‘gold standard’ technique for the detection of active gastric Helicobacter pylori infection and is recommended as the best option for “test-and-treat” strategy in primary health care centers.

Aim: To compare the performance of capsulated and non-capsulated 14C-UBT protocols for the detection of H. pylori infection in patients.

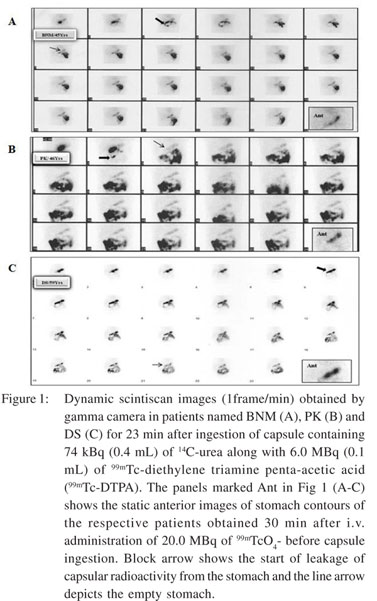

Methods: Fifty eight H. pylori infected patients underwent routine upper GI endoscopy and biopsies were processed for rapid urease test (RUT) and histopathology examination. Capsulated 14C-UBT was done in a novel way by using 74 kBq of 14C-urea along with 6.0 MBq of 99mTc-diethylene triamine penta-acetic acid (99mTc-DTPA) to simultaneously monitor the movement and the fate of ingested capsule after delineating the stomach contour by using 20.0 MBq of 99mTechnetium pertechnetate (99mTcO4-) under dual head gamma camera. Noncapsulated 14C-UBT was performed within 2 days of the previous test and the results of these protocols were compared.

Results: In 3 out of 58 H. pylori positive cases (5.17%), 14C-UBT results were found to be negative by using the capsulated method. Interestingly, on monitoring the real time images of the capsule in these cases it was found that misdiagnosis of H. pylori infection occurred mainly due to either rapid transit of the 14C-urea containing capsule from the upper gastric tract or its incomplete resolution in the stomach during the phase of breath collection. Conclusion: Use of non-capsulated 14C-UBT protocol appears to be a superior option than the conventional capsule based technique for the detection of H. pylori infection.

|

48uep6bbphidvals|514 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Helicobacter pylori infection has been incriminated for many diseases of the upper gastrointestinal tract[1] and is also believed to be associated with many other non-gastric diseases.[2] It is estimated that more than half of the adult population in the developed world and more than 80% of that in the developing countries is infected with this bacterium.[3,4]

Conventionally the 14C-urea breath test (UBT) with its high diagnostic accuracy (>95%) is employed worldwide for the detection of H. pylori infection, for follow-up after eradication of infection and for epidemiological purposes. A large body of data leading to this conclusion has been recently considered by the Maastricht Consensus Report which concurred that UBT is a simple, non-invasive, practical, highly accurate and reproducible test of choice for the confirmation of H. pylori infection.[5] The main advantage of this test is that it samples the whole stomach and thus prevents any sampling error because of patchy distribution of these microorganisms in the stomach.[6]

Marshall and Surveyor in 1988[7] introduced a non-capsulated liquid based 14C -UBT for detection of active H. pylori infection. To avoid the problem of 14C-urea hydrolysis in the oropharynx owing to the presence of urease producing microorganisms, this test was subsequently modified by Hamlet and his coworkers in 1995.[8] These authors recommended the administration of the tracer (14C-urea) in a gelatin capsule to prevent the release of 14C-urea before reaching the stomach and to avoid overlapping results between infected and noninfected patients. At present majority of diagnostic centers employ the capsulated 14C-UBT protocol[9-11] while others use the non-capsulated protocol.[12,13]

Till date, only two reports have been published in literature which compared the data of capsulated versus non-capsulated 14C-UBT protocols in H. pylori infected and non-infected subjects.[8,14] The major limitation of these studies were that the authors did not instruct the subjects to brush their teeth and rinse their mouths before performing the non-capsulated 14CUBT test, a prerequisite strongly advocated by the earlier workers.[7,15] In addition, the test conditions were not identical to facilitate comparison of these two 14C-UBT protocols.[14] No study so far has been done to monitor the movement of [14]Curea containing capsule after its ingestion and to know the extent of its dissolution in the stomach while collecting the breath samples.

Considering the above lacunae, we developed a novel design for our study by employing a 14C-UBT-cum-scintigraphy technique to simultaneous monitor the real-time movement of the capsule in the upper gastric tract while performing the 14CUBT. The aim of our preliminary study was to compare the results of capsulated versus non-capsulated 14C-UBT protocols in H. pylori infected patients. Our studies demonstrate how sometimes H. pylori infection can be misdiagnosed due to either rapid transit of the 14C-urea containing capsule from the upper gastric tract or its incomplete resolution in the stomach during the phase of breath collection after ingestion. In this article we present three cases which were misdiagnosed for H. pylori infection using the capsulated protocol but were confirmed on using the non-capsulated method.

Methods

Subjects

Fifty eight patients (41 males; 17 females; mean age 40.05 ± 10.86 years; range 19-71 years) with upper gastrointestinal symptoms referred from Gastroenterology department of Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India were included in this study. Upper GI endoscopy was done and multiple biopsies were obtained from each patient for rapid urease test (RUT) and histopathology examination. None of these patients had taken any drugs that interfered with the UBT results.[16] The Ethics Committee of the Institute cleared the study and each of these patients gave written informed consent. 14C-urea breath test (14C-UBT): Non-capsulated UBT 14C-urea of high specific activity (1.85 GBq/mmol, Amersham, UK) was dissolved in triple distilled autoclaved water, dispensed in small sterilized vials and stored at -20°C till further use.

Non-capsulated 14C-UBT was performed as reported earlier[17] and the patient was prepared for the procedure as described elsewhere.[15] Briefly, overnight fasting patients were asked to thoroughly brush their teeth and rinse their mouths to get rid of oral urease producing commensal flora just before starting the UBT. Each patient was given 74 kBq of 14C-urea (0.4 mL) in 10 mL of water with the instruction to swallow it immediately followed by additional 250 mL of drinking water. One breath sample was obtained before ingestion of 14C-urea (to serve as background) and others at 10, 15 and 20 min directly into a CO2 trapping solution containing 0.5 mmol ethanolic benzethonium hydroxide in 10 mL toluene-based scintillation fluid along with a drop of alcoholic phenolphthalein as a pH indicator. Breath samples were collected until the color of the trapping solution changed from pink to colorless. Radioactivity in breath samples was measured as disintegration per minute (DPM) mode in liquid scintillation counter (Wallac 1409, Finland). The results were expressed as 14CO2/mmol CO2 exhaled as percent of administered 14C-urea dose and a value higher than 0.006% at any one time point was considered as an indicator of H. pylori infection.[18]

Capsulated UBT

14C-UBT study was repeated within 2 days of the first breath test using 0.5 mL capacity pharmaceutical grade gelatin capsule (M/S Parke Davis, USA). A background breath sample was obtained in trapping solution before starting the 14C-UBT. Each patient was given 74 kBq (0.4 mL) of 14C-urea along with 6.0 MBq (0.1 mL) of 99mTc-diethylene triamine penta-acetic acid (99mTc-DTPA) in a capsule. The capsule was prepared in less than 15 sec to maintain its strength. The patient was instructed to swallow the capsule immediately with 250 mL of drinking water. Breath samples were obtained up to 20 min as stated earlier and radioactivity was measured. 99mTc-DTPA being a non-absorbable marker was used in the capsule to monitor its real time movement in the stomach.[19]

Scintiscanning

Prior to conducting the capsulated 14C-UBT, the stomach contour of each patient was delineated as baseline reference for monitoring the fate of capsule. For this, each overnight fasting patient was initially injected intravenously 20.0 MBq of 99mTechnetium pertechnetate (99mTcO4 -). After half an hour static anterior scintiscan images of upper abdomen were obtained for one min on gamma camera (dual head singlephoton emission computed tomography; E-Cam, Siemens, Germany) with the patient lying in supine position. Thereafter the patient was administered a gelatin capsule containing 14Curea and 99mDTPA orally, as stated earlier. Immediately dynamic scintiscanning of anterior aspect of abdomen was done for 23 min and images were acquired at the rate of one frame per min. During acquisition of the images, breath samples were also collected.

Results

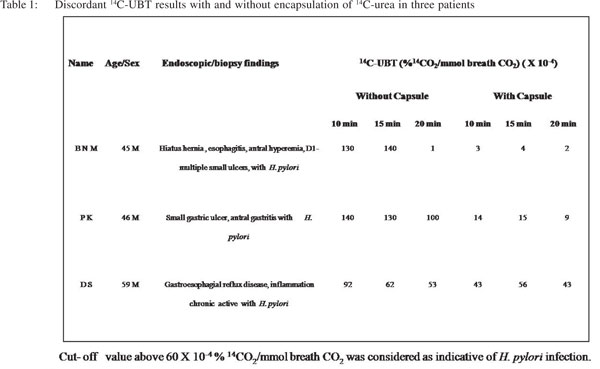

Out of 58 H. pylori infected cases (confirmed with histological evaluation, RUT and non-capsulated 14C-UBT protocol), 3 (5.17%) were found to be negative for H. pylori using capsulated the 14C-UBT protocol. Table 1 shows discriminate 14C-UBT values with and without encapsulation of 14C-urea in these cases. By employing the non-capsulated protocol, we observed that the breath 14CO2 values in these patients were higher than the cut-off value at two or more time points; whereas by using the capsulated method the test values remained low at all the time points.

In this study, we showed real time movement of the 14Curea containing capsule in the upper gastric tract with scintigraphic imaging using 99mDTPA as a gastric emptying marker. These images revealed that the misdiagnosis of H. pylori infection occurred mainly due to either rapid transit of the capsule from the upper gastric tract or its incomplete resolution in the stomach during the phase of breath collection after ingestion. Figure 1 (A-C) shows the scintiscans of 3 patients in whom discordant 14C-UBT results were obtained by employing the capsulated and non-capsulated protocols. For reference, the anterior contours of the stomach obtained 30 min after iv administration of 99mTcO4 - and before capsule ingestion are shown for each patient in order to exactly monitor the position and status of the ingested capsule. The clinical and 14C-UBT data of each patient is given below: Case No. 1: BNM, 45 years male, reported with symptoms of dyspepsia. Upper GI endoscopy and antral biopsy revealed hiatus hernia, esophagitis, antral hyperemia, multiple small ulcers in duodenum with presence of H. pylori infection. Scintigraphic image frame 3 of Figure 1A, shows that the capsule started leaking within 3 min of its ingestion and the tracer (14C-urea) moved out completely from the stomach within 7-8 min. Thus the scintigraphic images clearly demonstrate that there was total absence of 14C-urea in the stomach at the time when breath samples were collected at 10, 15 and 20 min. Hence, the capsulated 14C-UBT results did not show any presence of H. pylori infection. On the other hand, noncapsulated 14C-UBT results at 10 and 15 min were clearly indicative of H. pylori infection (Table 1).

Case No. 2: PK, 46 years male, reported with suspected dyspepsia. Upper GI endoscopy and antral biopsy revealed small gastric ulcer, antral gastritis with H. pylori infection. Scintigraphic image frame 2 of Figure 1B, shows that the capsule started leaking within 2 min of its ingestion and the tracer (14C-urea) almost moved out completely from the stomach within 3 min which subsequently entered into the intestine leaving the stomach completely free of tracer. The scintigraphic images demonstrate complete absence of 14C-urea in the stomach at 10 min. This resulted in negative 14C-UBT with capsulated UBT protocol; whereas, non-capsulated 14C-UBT results at all time points revealed the presence of H. pylori infection (Table 1).

Case No. 3: DS, 59 years male, reported with symptoms ofgastro-esophageal reflux disease. Upper GI endoscopy and antral biopsy revealed chronic active inflammation with H. pylori infection. Scintigraphic image frame 6 of Figure 1C shows that the capsule started leaking at sixth min and its contents started moving towards the duodenum. Subsequently, at the eighth min the entire capsule with its tracer moved out of the stomach leaving only trace amount of the 14C-urea in the stomach, which resulted in generation of low quantity of 14CO2 at all time points. Whereas, the non-capsulated 14C-UBT protocol showed exhalation of significant amount of 14CO2 especially at 10 and 15 min indicating the presence of H. pylori infection (Table 1).

Discussion

In this study, we report three H. pylori positive cases where we obtained discordant results of 14C-UBT by using the capsulated and non-capsulated protocols and found the noncapsulated method to be a superior option than the capsulated one for the diagnosis of H. pylori infection. This is the first study, which provides direct scintigraphy based evidence indicating that the misdiagnosis of H. pylori infection can occur mainly due to either rapid transit of 14C-urea containing capsule from the upper gastric tract or its incomplete resolution in the stomach during the phase of breath collection after ingestion. The capsulated 14C-UBT was introduced to avoid the problem of 14C-urea hydrolysis in the oropharynx due to presence of urease producing microorganisms and also to prevent the release of 14C-urea before it reaches the stomach.[8] These authors compared the results of capsulated and noncapsulated 14C-UBT protocols in a small number of patients without any consideration of their oral hygiene. They concluded that capsulated 14C-UBT protocol obviates the problem of false positive results in early breath samples and makes it possible to diagnose H. pylori infection with 99.8% reliability from a single 10 min breath sample. Further, Lerang et al[14] reported better specificity of capsulated 14C-UBT than the non-capsulated protocol (97% vs. 89%) with equal sensitivity for both (100%). While comparing both the 14CUBT protocols these authors did not keep the test conditions identical in terms of amount of tracer dose administered, timings of breath collection, expression of results etc. In addition, none of the above mentioned studies monitored the movement and fate of 14C-urea containing capsule after its ingestion. In the present study, while keeping all the test parameters identical we used a non-absorbable tracer marker (99mDTPA) along with 14C-urea in a capsule that helped us to delineate the exact position and fate of the capsule in the stomach while collecting breath samples for UBT simultaneously. In 2 of the present 3 discordant cases, the capsule with its contents moved out of the stomach before the first breath sample was obtained at 10 min; whereas in 1 case (DS) traces of 14C-urea leaked from the capsule in stomach which resulted in breath 14CO2 level below the cut-off value at all time points despite the fact that the patient had H. pylori infection. Thus there was no chance for 14C-urea present in the capsule to come in contact with the H. pylori infected site(s) in the stomach yielding false negative tests in these patients. On the other hand, employing the non-capsulated 14C-UBT protocol facilitated 14C-urea to immediately make contact with the entire stomach mucosa thereby initiating prompt hydrolysis of the urea by the H. pylori urease enzyme, as has been shown in Table 1.

Due to its high accuracy (>95%), the 14C-UBT assay provides a clinical “gold standard” against which the accuracy of other tests for the diagnosis of H. pylori infection can be validated.[9,14,20-23] Our preliminary observations showed that for the detection of active H. pylori infection, the use of liquid based non-capsulated 14C-UBT protocol appears to be a better option for the patients. However, it is important to validate these findings in a larger cohort of patients before we can draw tangible conclusions for patient management.

Case No. 3: DS, 59 years male, reported with symptoms ofgastro-esophageal reflux disease. Upper GI endoscopy and antral biopsy revealed chronic active inflammation with H. pylori infection. Scintigraphic image frame 6 of Figure 1C shows that the capsule started leaking at sixth min and its contents started moving towards the duodenum. Subsequently, at the eighth min the entire capsule with its tracer moved out of the stomach leaving only trace amount of the 14C-urea in the stomach, which resulted in generation of low quantity of 14CO2 at all time points. Whereas, the non-capsulated 14C-UBT protocol showed exhalation of significant amount of 14CO2 especially at 10 and 15 min indicating the presence of H. pylori infection (Table 1).

Discussion

In this study, we report three H. pylori positive cases where we obtained discordant results of 14C-UBT by using the capsulated and non-capsulated protocols and found the noncapsulated method to be a superior option than the capsulated one for the diagnosis of H. pylori infection. This is the first study, which provides direct scintigraphy based evidence indicating that the misdiagnosis of H. pylori infection can occur mainly due to either rapid transit of 14C-urea containing capsule from the upper gastric tract or its incomplete resolution in the stomach during the phase of breath collection after ingestion. The capsulated 14C-UBT was introduced to avoid the problem of 14C-urea hydrolysis in the oropharynx due to presence of urease producing microorganisms and also to prevent the release of 14C-urea before it reaches the stomach.[8] These authors compared the results of capsulated and noncapsulated 14C-UBT protocols in a small number of patients without any consideration of their oral hygiene. They concluded that capsulated 14C-UBT protocol obviates the problem of false positive results in early breath samples and makes it possible to diagnose H. pylori infection with 99.8% reliability from a single 10 min breath sample. Further, Lerang et al[14] reported better specificity of capsulated 14C-UBT than the non-capsulated protocol (97% vs. 89%) with equal sensitivity for both (100%). While comparing both the 14CUBT protocols these authors did not keep the test conditions identical in terms of amount of tracer dose administered, timings of breath collection, expression of results etc. In addition, none of the above mentioned studies monitored the movement and fate of 14C-urea containing capsule after its ingestion. In the present study, while keeping all the test parameters identical we used a non-absorbable tracer marker (99mDTPA) along with 14C-urea in a capsule that helped us to delineate the exact position and fate of the capsule in the stomach while collecting breath samples for UBT simultaneously. In 2 of the present 3 discordant cases, the capsule with its contents moved out of the stomach before the first breath sample was obtained at 10 min; whereas in 1 case (DS) traces of 14C-urea leaked from the capsule in stomach which resulted in breath 14CO2 level below the cut-off value at all time points despite the fact that the patient had H. pylori infection. Thus there was no chance for 14C-urea present in the capsule to come in contact with the H. pylori infected site(s) in the stomach yielding false negative tests in these patients. On the other hand, employing the non-capsulated 14C-UBT protocol facilitated 14C-urea to immediately make contact with the entire stomach mucosa thereby initiating prompt hydrolysis of the urea by the H. pylori urease enzyme, as has been shown in Table 1.

Due to its high accuracy (>95%), the 14C-UBT assay provides a clinical “gold standard” against which the accuracy of other tests for the diagnosis of H. pylori infection can be validated.[9,14,20-23] Our preliminary observations showed that for the detection of active H. pylori infection, the use of liquid based non-capsulated 14C-UBT protocol appears to be a better option for the patients. However, it is important to validate these findings in a larger cohort of patients before we can draw tangible conclusions for patient management.

Our study concludes that the use of non-capsulated [14]CUBT appears to be a superior option over the conventional capsule based protocol for detection of H. pylori infection. Comparative data from a large number of patients needs to be generated further before one can arrive at definitive conclusions.

Declaration of funding

The study was supported by grants received from the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), Government of India, vide Reference IRIS No. 2006-02600.

References

- Williams MP, Pounder RE. Helicobacter pylori: from the benign to the malignant. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:S11–6.

- Pathak CM, Kaur B, Khanduja KL. 14C-urea breath test is safefor pediatric patients. Nucl Med Commun. 2010;31:830–5.

- Graham DY, Malaty HM, Evans DG, Evans DJ Jr, Klein PD, Adam E. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori in an asymptomatic population in the United States. Effect of age, race, and socioeconomic status. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:1495–501.

- Hoang TT, Bengtsson C, Phung DC, Sorberg M, Granstrom M. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in urban and rural Vietnam. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005;12:81–5.

- Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain C, Bazzoli F, El-Omar E, Graham D, et al. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht III Consensus Report. Gut. 2007;56:772–81.

- Bayerdörffer E, Lehn N, Hatz R, Mannes GA, Oertel H, Sauerbruch T, et al. Difference in expression of Helicobacter pylori gastritis in antrum and body. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:1575–82.

- Marshall BJ, Surveyor I. Carbon-14 urea breath test for the diagnosis of Campylobacter pylori associated gastritis. J Nucl Med. 1988;29:11–6.

- Hamlet AK, Erlandsson KI, Olbe L, Svennerholm AM, Backman VE, Pettersson AB. A simple, rapid, and highly reliable capsulebased 14C urea breath test for diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:1058–63.

- Petroviæ M, Artiko V, Novosel S, Ille T, Šobiæ-Šaranoviæ D, Pavloviæ S, et al . Relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection estimated by 14C-urea breath test and gender, blood groups and Rhesus factor. Hell J Nucl Med. 2011;14:21–4.

- Khuroo MS, Khuroo NS, Khuroo MS. Diffuse duodenal nodular lymphoid hyperplasia: a large cohort of patients etiologically related to Helicobacter pylori infection. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11:36.

- Yakoob J, Jafri W, Abbas Z, Abid S, Naz S, Khan R, et al. Risk factors associated with Helicobacter pylori infection treatment failure in a high prevalence area. Epidemiol Infect. 2011;139:581–90.

- Raju GS, Smith MJ, Morton D, Bardhan KD. Mini Dose (1-µCi) 14C-urea breath test for the detection of Helicobacter pylori. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:1027–31.

- Pathak CM, Avti PK, Bunger D, Khanduja KL. Kinetics of 14- carbon dioxide excretion from 14C-urea by oral commensal flora. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1603–7.

- Lerang F, Haug JB, Moum B, Mowinckel P, Berge T, Ragnhildstveit E, et al. Accuracy of IgG serology and other tests in confirming Helicobacter pylori eradication. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:710–5.

- Pathak CM, Bhasin DK, Panigrahi D, Goel RC. Evaluation of 14C-urinary excretion and its comparison with 14CO2 in breath after 14C-urea administration in Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:734–8.

- Bhasin DK, Singh V, Ayyagari A, Malik AK, Mehta SK. Effect of various anti-ulcer drugs on rapid urease test for Campylobacter pylori infection. Lancet 1989;2:918–9.

- Pathak CM, Bhasin DK, Nada R, Bhattacharya A, Khanduja KL. Changes in gastric environment with test meals affect the performance of 14C-urea breath test. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:1260–5.

- Kaul A, Bhasin DK, Pathak CM, Ray P, Vaiphei K, Sharma BC, et al. Normal limits of 14C-urea breath test. Trop Gastroenterol. 1998;19:110–3.

- Kurita N, Shimada M, Chikakiyo M, Miyatani T, Higashijima J, Yoshikawa K, et al. Does Roux-en Y reconstruction with jejunal pouch after total gastrectomy prevent complications of postgastrectomy? Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55:1851–4.

- Stojkoviæ MLj, Durutoviæ DR, Petroviæ MN, Stojkoviæ MV, Petroviæ NS, Antiæ AA, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection in various groups of patients studied, estimated by 14C-urea breath test. Acta Chir Iugosl. 2011;58:95–8.

- Rasool S, Abid S, Jafri W. Validity and cost comparison of 14carbon urea breath test for diagnosis of H pylori in dyspeptic patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:925–9.

- Pathak CM, Bhasin DK, Pramod KA, Khanduja KL. 14C-urea breath test as a ‘gold standard’ for detection of Helicobacter pylori infection. Med Sci Monit. 2004;10:LE14–5.

- Logan RP. Urea breath tests in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Gut. 1998;43:S47–50.

|

|

|

|

|

|