48uep6bbphidvals|387

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Introduction

Intussusception, the invagination of proximal intestinal segment into the distal segment is a common cause of pediatric intestinal obstruction. Intussusception in adult population is rare; accounting for only 5% of all intussusceptions.[1] It has been reported that (i) acute intestinal obstruction is the presenting feature in only 10-15% patients[2] of adult intussusception, and (ii) progression to strangulation and gangrene is uncommon. Preoperative clinical diagnosis of adult intussusception is difficult due to nonspecific symptoms and signs, and is most commonly established at the time of operation. We present our experience of nine cases of this rare entity to highlight the need for prompt diagnosis and surgical intervention in view of development of high frequency of associated bowel strangulation.

Methods

This retrospective study was conducted in a single surgical unit of a tertiary care teaching hospital from north India, from July 2003 to October 2009. The records of all patients older than 18 years with the final diagnosis of intussusception were reviewed. Details concerning the clinical presentation, management, and histopathological diagnosis were retrieved from case records.

Results

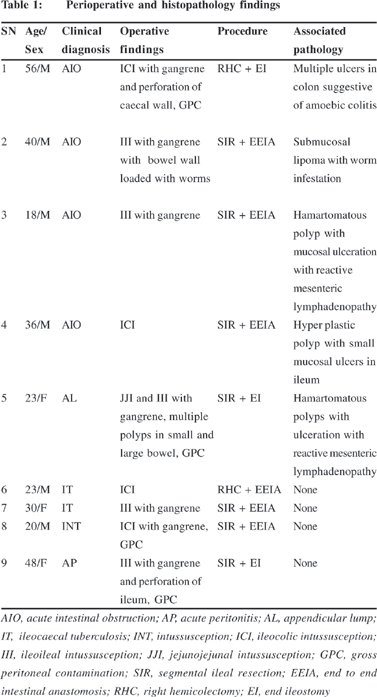

Nine patients were managed for intussusception during the period of study. The mean age of the patients was 32.6 ± 13.2 years (range 20-56 years). Men outnumbered women in the series in a ratio of 2:1. The median duration of symptoms was 8 days, which varied from 2 to 180 days. All patients had recurrent colicky abdominal pain and vomiting as presenting symptoms. One patient complained of bleeding per rectum. Past history of abdominal surgery was present in two patients. Five patients (Table 1), who had acute presentation were diagnosed as acute intestinal obstruction (4) and perforation peritonitis (1); and were operated on the same day. Remaining four patients had subacute/chronic presentation and all of them had lump in right iliac fossa. These patients were clinically diagnosed as appendicular lump (1), ileocaecal tuberculosis (2), and intussusception (1). Ultrasonography suggested intussusception in all the four patients. All the patients underwent exploratory laparotomy under general anesthesia. Hydrostatic reduction was not attempted in any of the patient. The operative findings, operative procedure, and associated pathology are shown in Table 1. Four patients had ileo-colic intussusception while ileo-ileal type was identified in the remaining five. One patient with ileo-ileal type intussusceptions had jejuno-jejunal intussusception also. Seven of the 9 patients (77%) had gangrene of affected bowel. Two of our patients had perforation in the intussuscepient. Resection of the intestinal segment containing intussusception was done in all patients. Primary anastomosis was carried out in five patients while temporary diverting ileostomy was done in four patients in view of gross peritoneal contamination. Postoperative complications were noted in 5/9 patients: wound infection (3), anastomotic dehiscence (1), and severe sepsis and multi organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) (1). One patient who developed severe sepsis and MODS died on 5th postoperative day. Histopathological examination revealed that five patients had lesions which could have contributed to development of intussusception: submucous lipoma (1), intestinal polyp (3), and amoebic colitis (1). None of our patients had associated malignancy. The ileostomy in three patients was closed during a successive admission. One patient had multiple polyps in small and large bowel. She was referred to a gastroenterologist for further evaluation, but was lost to follow up. Another patient had associated intestinal worms. They were discrete and were not forming bolus. As many worms as possible were milked out from the open ends of bowel during resection. He was given antihelminthics (Albendazole 400 mg) on 5th postoperative day (after return of intestinal motility) and after 6 weeks.

Discussion

Patients of adult intussusception have a varied clinical presentation that can be acute, subacute, or chronic. The classical triad of pain abdomen, abdominal lump and red currant jelly is rarely encountered in cases of adult intussusception. Only one of our patients (11%) had this classical triad. Wang et al, in their review of 41 cases of adult intussusception, reported that only 9.8% of patients had this classical triad.[3]

Colicky abdominal pain and vomiting are the two most common symptoms in our study. Pain has been reported to be the most common symptom, being present in 71-90% of patients, followed by vomiting and bleeding per rectum.[3] Four patients (44%) in our series had abdominal lump which is consistent with other reported case series (24-42% of cases).[4]

The patients in our study had two distinct clinical presentations. Patients with associated absolute constipation and abdominal distension had a more acute presentation, requiring emergency laparotomy. Patients with a palpable right iliac fossa lump in a non-distended abdomen had less pronounced symptoms and allowed further diagnostic imaging prior to intervention. The clinical diagnosis of intussusceptions is uncommon in patients presenting with acute small gut obstruction, although it may be considered as a differential diagnosis along with appendicular lump, ileocaecal tuberculosis, and carcinoma caecum in patients having subacute/chronic presentation and a right lower abdominal lump.

The preoperative diagnosis of intussusception can be established by imaging studies. Abdominal CECT is the most accurate imaging modality for intussusception followed by ultrasound.[3] Pathognomonic CECT appearance of intussusception is a complex soft tissue mass, consisting of the outer intussuscipiens and the central intussusceptum with an eccentric area of fat density within the mass representing the intussuscepted mesenteric fat, and the mesenteric vessels are often visible within it. The intussusception will appear as a sausage-shaped mass when the CT beam is parallel to its longitudinal axis, but will appear as a ‘‘target’’ mass when the beam is perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the intussusception on the intussuscipiens.[5] Ultrasound of abdomen is very useful in a developing country like India, where emergency CECT facility is not universally available. Ultrasonography may not be a satisfying investigation in acute presentation as findings are difficult to appreciate in view of gas filled bowel loops.[3] But it proved to be a good investigation in our patients with subacute/chronic features.

Ultrasonography could diagnose intussusception in all four patients who presented with subacute/chronic features. Classical sonographic features include the “target” or “doughnut” signs on the transverse view and the “pseudokidney” sign or the “hay-fork” sign in the longitudinal view.[6] Unfortunately, ultrasound is operator dependent and demonstration of these findings requires handling and interpretation by an experienced radiologist, in order to confirm the diagnosis.

Intussusception can have varied aetiology: benign, malignant or idiopathic. It can occur secondary to the presence of inflammatory lesions, Meckel’s diverticulum, postoperative adhesions, lipoma, adenomatous polyps, lymphoma, and metastases, or it may be iatrogenic, e.g. due to the presence of an intestinal tube or even in patients with a gastrojejunostomy.[7]

An underlying pathological lead point is present in about 90% cases of adult intussusception.[8] Four of our patients (44%) had distinct lead points (two had hamartomatous polyp, and one each had hyperplastic polyp and submucosal lipoma), while one patient showed features of amoebic colitis. In our series, four patients were labeled as idiopathic intussusceptions in view of absence of any identifiable pathology. Small bowel intussusceptions are usually benign in nature with a rate of 50- 75% as reported in many series.[9] Malignant lesions causing intussusception in small bowel are usually metastatic in nature, malignant melanoma being the most common. Though Wang et al[3] reported that malignant lesions causing colonic intussusception were present in 37.5% of cases in a recent retrospective review of 41 adult patients of intussusception, most studies observed malignant lesions in 69 – 100 % of large bowel intussusception in adults.[10,11] Interestingly, none of our patients had associated malignancy.

Engulfment of the mesentery by the intussusception mass puts traction on the mesenteric vascular arcades leading to compression and angulation of mesenteric vessels with subsequent obstruction, ischemia, and eventually necrosis. The resultant ischemic necrosis/gangrene is evident at the apex of the intussusceptum and extends proximally.[12] Bowel necrosis occurs in 8-12 hours from the onset of symptoms. This time period is very crucial as early exploration on diagnosis may prevent ischemic changes. Median duration of presentation in our patients was 8 days. Seven patients (77%) were found to have small bowel gangrene on laparotomy although the abdominal signs of strangulation were present in only one patient. The lack of peritoneal signs of bowel strangulation in most of our patients may be explained due to presence of adhesions/edema at the neck of the intussusception causing isolation of the gangrenous tip within a normal segment of bowel. Secondary pressure on the intussuscipiens may result in ischemic necrosis of its outer layer resulting in free perforation[12] as seen in two of our patients.

High frequency of bowel gangrene in our patients is remarkable. There is paucity of data in literature about association of bowel gangrene in adult intussusception as most authors have focused on associated malignancy and have not given attention to gangrene.1,5,13,14 However, Wang et al[10] reported bowel gangrene, necrosis with perforation, transmural infarction or ischemia in 8 (33.3%) of his patients. A critical analysis of 160 patients of adult intussusception reported by Weilbaecher et al in 1971[15] revealed a number of cases having associated bowel gangrene. He reported gangrene in a case of primary intussusception and passage of a large segment of gangrenous intestine by a pregnant woman two weeks following bypass for an ileocolic intussusception. In another 15 patients in this large series, gangrene of the bowel was proposed to be one of the reasons for justifying resection. It is evident that gangrene of bowel is not uncommon in adult intussusceptions. Long duration of symptoms and delay in diagnosis are important reasons for development of ischemia of intussusceptions in adults. Presence of gangrene in the intussusception is an important consideration in deciding the operative procedure in an individual patient and it also affects prognosis.

The optimal treatment of adult intussusception is debatable. Most surgeons believe that preoperative reduction with barium or air has no place in the management of adult intussusceptions in contrast to pediatric patients where intussusception is primary and benign.[12] Adult intussusception requires surgical intervention in view of large proportion of underlying abnormalities and associated neoplasm.[8] In our series, 77% patients had associated bowel gangrene which further emphasizes role of surgical intervention in these patients. There is a debate regarding the extent of resection: primary en bloc resection versus initial reduction and limited resection.[10] High frequency of associated malignancy especially in colonic intussusception has been a strong point in favor of primary enbloc resection. Besides that, intraluminal and intraperitoneal seedling of tumor cells/bacteria and increased risk of anastomosis leak in friable and edematous bowel clearly mandates primary en bloc resection.[13,14,16] Low incidence of malignancy in small bowel intussusception may be dealt with limited bowel resection so as to avoid short bowel syndrome.[17]

None of our patients proved to be harboring malignancy. We still believe resection, without attempt of initial reduction, should be done in all adult patients with intussusceptions because of high incidence of gangrene in intussusceptum and to avoid handling of friable and edematous bowel which may cause dissemination of bacteria and anastomotic complications. Each case should be individualized at the time of surgery. Recently, minimally invasive techniques are being explored in the management of adult intussusception.[18,19] Laparoscopic exploration depends upon on the clinical condition of a patient, the location and extent of intussusception, the nature of underlying disease, and the availability of surgeons with sufficient laparoscopic expertise.[20] Laparoscopy can facilitate prompt diagnosis in suspected cases of intussusception. It also aids in the planning of abdominal incision if open or laparoscopic assisted resection is being contemplated. One of our patients had associated intestinal worms.

Milking of the worms through the open ends of the bowel during resection is recommended in these cases. After surgical treatment, patients should be prescribed antihelminthic drugs after the recovery of bowel sounds and a second dose should be repeated after six weeks.[21]

It can be concluded that all patients, who have recurrent abdominal colicky pain and vomiting suggestive of intermittent/ partial obstruction and abdominal lump, should be considered to have intussusception and should be subjected to urgent imaging studies. Though CT scan is the investigation of choice, ultrasonography in experienced hands proves to be a good diagnostic modality in developing countries. The high frequency of bowel gangrene encountered in patients of adult intussusception mandates prompt surgical intervention upon diagnosis.

References

1. Azar T, Berger DL. Adult intussusception. Ann Surg.1997;226:134–8.

2. Dean DL, Ellis FH Jr, Sauer JW. Intussusception in adults. ArchSurg. 1956;73:6–11.

3. Wang N, Cui XY, Liu Y, Long J, Xu YH, Guo RX, et al. Adult intussusception: A retrospective review of 41 cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3303–8,

4. Yalamarthi S, Smith RC. Adult intussusception: case reports and review of literature. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:174–7.

5. Gayer G, Zissin R, Apter S, Papa M, Hertz M. Pictorial review: adult intussusception—a CT diagnosis. Br J Radiol. 2002;75:185–90.

6. Boyle MJ, Arkell LJ, Williams JT. Ultrasonic diagnosis of adult intussusception. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:617–8.

7. Jain BK, Lodh U, Chandra SS, Hadke NS, Ananthakrishanan N, Mehta RB, et al. Jejunogastric intussusceptions: therapeutic options. Aust N Z J Surg. 1989;59:865–8.

8. Marinis A, Yiallourou A, Samanides L, Dafnios N, Anastasopoulos G, Vassiliou I, et al. Intussusception of the bowel in adults: a review. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:407–11.

9. Cera SM. Intestinal intussusception. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2008;21:106–13.

10. Wang LT, Wu CC, Yu JC, Hsiao CW, Hsu CC, Jao SW. Clinical entity and treatment strategies for adult intussusceptions: 20 years’ experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1941–9.

11. Goh BK, Quah HM, Chow PK, Tan KY, Tay KH, Eu KW, et al. Predictive factors of malignancy in adults with intussusception. World J Surg. 2006;30:1300–4.

12. DiFiore JW. Intussusception. Semin Pediatr Surg. 1999;8:214–20.

13. Yakan S, Calýskan C, Makay O, Deneclý AG, Korkut MA. Intussusception in adults: clinical characteristics, diagnosis and operative strategies. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1985–9.

14. Eisen LK, Cunningham JD, Aufses AH Jr. Intussusception in adults: institutional review. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;188:390–5.

15. Weilbaecher D, Bolin JA, Hearn D, Ogden W 2nd. Intussusception in adults. Review of 160 cases. Am J Surg. 1971;121:531–5.

16. Barussaud M, Regenet N, Briennon X, de Kerviler B, Pessaux P, Kohneh-Sharhi N, et al. Clinical spectrum and surgical approach of adult intussusceptions: a multicentric study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006;21:834–9.

17. Begos DG, Sandor A, Modlin IM. The diagnosis and management of adult intussusception. Am J Surg. 1997;173:88–94.

18. Alonso V, Targarona EM, Bendahan GE, Kobus C, Moya I, Cherichetti C, et al. Laparoscopic treatment for intussusceptions of the small intestine in the adult. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2003;13:394–6.

19. Jelenc F, Brencic E. Laparoscopically assisted resection of an ascending colon lipoma causing intermittent intussusception. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2005;15:173–5.

20. Akatsu T, Niihara M, Kojima K, Kitajima M, Kitagawa Y, Murai S. Adult colonic intussusception caused by cecum adenoma: successful treatment by emergency laparoscopy: report of a case. Surg Today. 2007;37:694–7.

21. Hefny AF, Saadeldin YA, Abu-Zidan FM. Management algorithm for intestinal obstruction due to ascariasis: a case report and review of the literature. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2009;15:301–5.