48uep6bbphidvals|360

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Introduction

The incidence of peptic ulcers has fluctuated considerably in the past. There was a rapid increase in its prevalence at the turn of the 20th century in the western countries. This has been followed by a notable decline in their incidence and prevalence over the past four decades,1,2,3 This decreasing trend is noticeable in the Asia-Pacific regions also.4,5,6,7,8

Studies in the past have shown that the occurrence of peptic ulcer disease has been influenced by seasonal changes, with a trend towards an increased incidence in the winter months.9,10,11 However, in a recent study, the time trends of neither endoscopic procedures nor endoscopic diagnoses revealed any seasonal variation or other cyclic pattern.12

Studies on time trend of peptic ulcer disease are not available from the Indian subcontinent. The purpose of this study was to identify changing trends in the occurrence of peptic ulcer with regard to the frequency, mean age of occurrence and gender specificity over a period of 16 years. It also aimed at testing the hypothesis that the diagnosis of duodenal and gastric ulcer at endoscopy may be influenced by change in the season.

Methods

In a retrospective study, the endoscopy records between the years 1989 and 2004 at our institution, which serves as a tertiary referral centre in Chennai were reviewed.

Individuals with an endoscopy diagnosis of duodenal or gastric ulcer or a combination of the two in a background of ulcer type dyspepsia were included for the study. Incidental detection of gastric or duodenal ulcer in cirrhosis of liver, post gastric surgery and upper GI malignancies were excluded. Details of age, gender, duration of symptoms, month and year of procedure, presence of duodenal or gastric ulcer or a combination, deformities in the pylorus and duodenum (deformed bulb) and presence of gastric outlet obstruction (GOO) were noted from the records. Gastric ulcers were classified based on the location as: Type I: ulcer in lesser curve incisura; Type II: prepyloric ulcer; Type III: gastric ulcer with duodenal ulcer; Type IV: Juxtacardiac gastric ulcer and Type V: Gastric ulcers in multiple sites.13,14,15

Seasonal variations were also noted. The climate of city of Chennai, located in the southern part of the Indian subcontinent, is for most of the months uniformly hot and humid. The months between November to February are pleasant with December and January being the coolest with less humidity. The monsoon season is from October to mid- December.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the chi-square test, one way ANOVA and Student t-test wherever appropriate. P value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

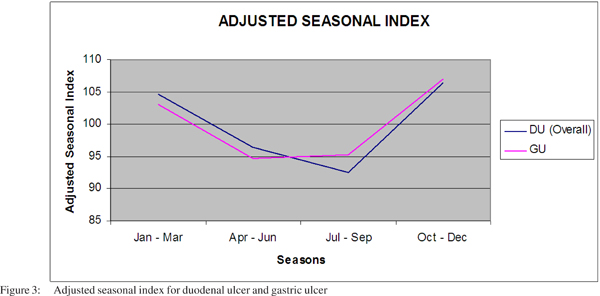

For the analysis of seasonal variation, each year was divided into 4 quarters (January-March, April-June, July- September & October-December) corresponding to the seasons. The raw data were plotted versus the month of endoscopy. Endoscopic diagnoses were then expressed as proportional rates per 100 endoscopies and procedural month. The study period (1989-2004) was divided into 4 groups (1989- 92, 1993-96, 1997-2000 & 2001-4) and proportional rates were calculated for each quarter (e.g. Jan-Mar) for the 4 groups respectively. 3-month moving averages were then calculated for each quarter and the seasonal index was derived as the mean of the 3 - month moving averages. Adjusted seasonal index was then calculated by adjusting the mean of the seasonal indices to 100.

Results

During the study period, 7365 patients had duodenal ulcer, 2834 patients had gastric ulcer (including the 1605 patients who had a combination of DU and GU), out of a total of 60205 endoscopy procedures.

Age and gender specific trends

Duodenal ulcer

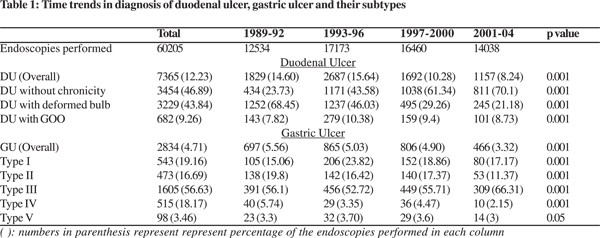

Among all the duodenal ulcers diagnosed during the study period, those with (43.84%) and without (46.89%) features of chronicity were equally prevalent. Gastric outlet obstruction (9.26%) was relatively uncommon (Table 1). The overall mean age of patients with duodenal ulcer was 39.1 ± 13.46 years.

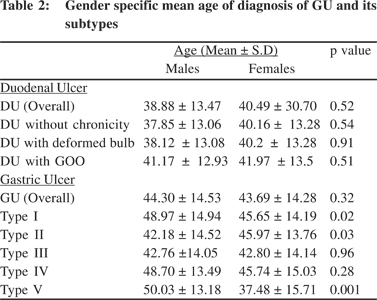

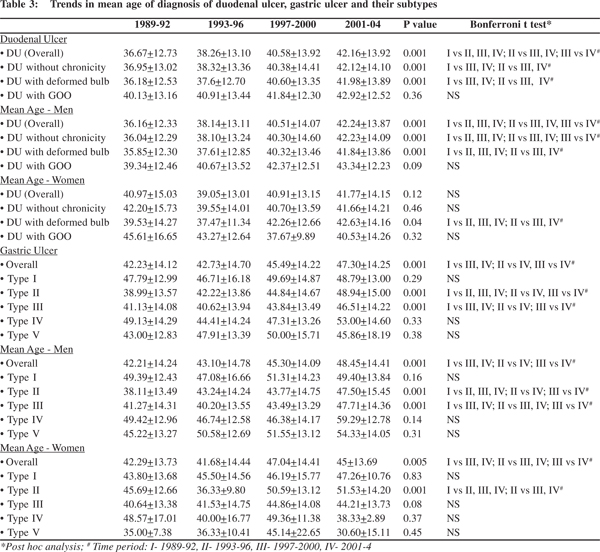

On gender specific analysis, there was no significant difference in the mean age of endoscopic diagnosis of DU between males and females (Table 2). An increase in the mean age of endoscopic diagnosis was noted across the four cohorts with regard to duodenal ulcers overall, DU without chronicity and DU with deformed bulb. A similar trend was observed among men and only for DU with deformed duodenal cap among women on gender specific analysis. No significant changes were seen with regard to DU with gastric outlet obstruction – overall and on gender specific analysis (Table 3).

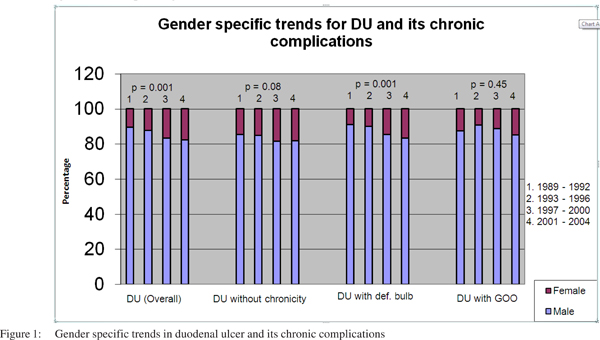

DU and all its subtypes occurred more commonly among men than women in all the four cohorts. However, over the years the proportion of women affected showed a significantly increasing trend with regard to duodenal ulcers overall and specifically for those ulcers with a deformed bulb. A similar trend was observed in patients with DU without chronicity, though levels of statistical significance were not reached (p = 0.08) (Figure 1).

Gastric ulcer

Among the gastric ulcers diagnosed during the study period, type III ulcers were the most common (Table 1). The mean age of diagnosis of gastric ulcer overall was 44.30 + 14.40 years.

Over the 16-year period, there was a significant increase in the mean age of endoscopic diagnosis of GU (Overall, i.e. including all the five subtypes) and for subtypes II and III. A similar trend was observed among men. Among women, there was an increase in the mean age of occurrence of GU (Overall) and type II GU (Table 3). On gender specific analysis, women presented at a significantly younger age than men for types I and V gastric ulcers (p values of 0.02 and 0.001 respectively) (Table 2).

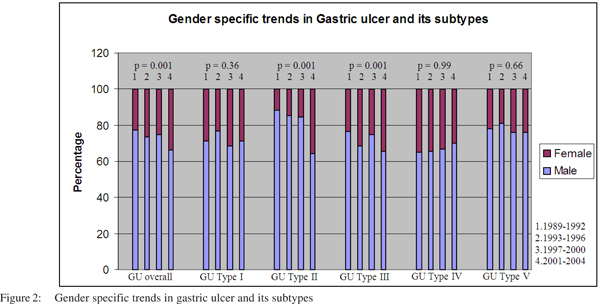

On gender specific analysis, GU and all its subtypes occurred more commonly among men than women in all the four cohorts. Over the years, there was an increase in the proportion of women affected by GU (overall) and for types II and III (Figure 2).

Time trends of ulcer diagnosis

There was a significant decrease in the endoscopic diagnosis of DU, GU and their subtypes over the years. The trend towards a decline started during the third cohort (1997-2000), though the number of endoscopies performed did not show any significant change (Table 1).

Seasonal index

The adjusted seasonal index, calculated for the endoscopic diagnosis of gastric ulcer and duodenal ulcer, showed a higher frequency of diagnosis of DU and GU during the relatively cooler months of October – March (Figure 3).

Discussion

The incidence of peptic ulcer disease has shown a fluctuating trend in the past. In the West, the incidence of peptic ulcer, particularly duodenal ulcer, rose sharply at the turn of the 19th to the 20th century but has declined considerably in the past three decades.[1,2] In the East, the rise was equally impressive, but the decline appears to have been delayed; only starting in the past decade.[4,5]

The present study focused on the trends in the endoscopic diagnosis of duodenal ulcers with its complications and also the gastric ulcer, over a period of 16 years with a total of 60,205 endoscopic procedures, from a tertiary referral centre in a southern state of the Indian subcontinent.

There was a significant trend towards an overall decrease in the endoscopic diagnosis of duodenal ulcers including its complications. A similar decreasing trend was observed for the endoscopic diagnosis of GU. This is consistent with observations from the west as well as from some Asian countries.[4,5,6,7] The declining trend has been attributed to an improvement in sanitation and hygiene resulting in a decrease in the rate of Helicobacter pylori infection and the widespread use of proton pump inhibitors.[3, 8]

Over the years, a greater proportion of females were found to have an endoscopic diagnosis of DU and GU. Also, the mean age of an endoscopic diagnosis of DU and GU has shown a steady increase during the study period. In the west, though there was a decline in the hospital admissions and mortality from peptic ulcer for most age groups between 1950-80[16,17]; admissions for perforated peptic ulcer and mortality from duodenal ulcer increased among elderly, especially women between the 1970s and 1980s.[17,18,19] Even in the era of proton pump inhibitors, admission rates for gastric and duodenal ulcer haemorrhage and duodenal ulcer perforation has increased among older subjects.[20] The rise in mortality and admissions among older women in the 1970s and 1980s has been attributed to the increased prescription of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, the other major cause of peptic ulcer, in older subjects.[21]

Studies in the past have shown that the time trends of gastric and duodenal ulcers are influenced by an underlying seasonal variation.[9] The occurrence of peptic ulcer is characterized by a winter high and a summer low.[10,11,12] The exact cause for this seasonal variation is unknown. It could be because viral infections and pneumonias that usually occur in winter may make the patients more susceptible to other diseases. Another reason could be that patients are less exposed to health care during the summer months because of vacations resulting in fewer encounters with physicians.[22,23,24] However, a recent U.S study based on a large database from several centers showed that the time trends of neither endoscopic procedures nor certain endoscopic diagnoses (such as duodenal ulcer and colorectal cancer) revealed any seasonal variation or other cyclic pattern.[12] In the present study, from the Indian subcontinent where a seasonal variation does not occur for most of the year, it was observed that the endoscopic diagnosis of duodenal or gastric ulcer was lower in the months between April to September and relatively higher between October to March.

References

1. Sonnenberg A. Temporal trends and geographical variations of peptic ulcer disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9:3–12.

2. Baron JH, Sonnenberg A. Hospital admissions for peptic ulcer and indigestion in London and New York in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Gut. 2002;50:568–70.

3. Sonnenberg A. Causes underlying the birth-cohort phenomenon of peptic ulcer: analysis of mortality data 1911–2000, England and Wales. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35:1090–97.

4. Goh KL, Wong HT, Lim CH, Rosaida MS. Time trends in peptic ulcer, erosive reflux esophagitis, gastric and esophageal cancers in a multiracial Asian population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:774–80.

5. Goh KL. Changing trends in gastrointestinal disease in the Asia- Pacific region. J Dig Dis. 2007;8:179–85.

6. Wong SN, Sollano JD, Chan MM, Carpio RE, Tady CS, Ismael AE, et al. Changing trends in peptic ulcer prevalence in a tertiary care setting in the Philippines: a seven-year study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:628–32.

7. Lam SK. Differences in peptic ulcer between East and West. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;14:41–52.

8. Pérez-Aisa MA, Del Pino D, Siles M, Lanas A. Clinical trends in ulcer diagnosis in a population with high prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:65–72.

9. Sonnenberg A, Wasserman IH, Jacobsen SJ. Monthly variation of hospital admission and mortality of peptic ulcer disease: a reappraisal of ulcer periodicity. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1192–8.

10. Stermer E, Levy N, Tamir A. Seasonal fluctuations in acute gastrointestinal bleeding. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;20:277–9.

11. Tsai CJ, Lin CY. Seasonal changes in symptomatic duodenal ulcer activity in Taiwan: a comparison between subjects with and without haemorrhage. J Intern Med. 1998;244:405–10.

12. Auslander JN, Lieberman DA, Sonnenberg A. Endoscopic procedures and diagnoses are not influenced by seasonal variations. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:267–72.

13. Rege RV, Jones DB. Current role of surgery in peptic ulcer disease. In Feldman M, Friedman LS, Sleisenger MH (eds): Gastrointestinal and liver disease 7th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders 2006.

14. Johnson HD. Gastric ulcer: classification, blood group characteristics, secretion patterns and pathogenesis. Ann Surg. 1965;162:990–96.

15. Csendes A, Braghetto I, Smok G. Type IV gastric ulcer: A new hypothesis. Surgery. 1986;101:361–2.

16. Coggon D, Lambert P, Langman MJ. 20 years of hospital admissions for peptic ulcer in England and Wales. Lancet. 1981;1:1302–4.

17. Walt R, Katschinski B, Logan R, Ashley J, Langman M. Rising frequency of ulcer perforation in elderly people in the United Kingdom. Lancet. 1986;1:489–92.

18. Jibril JA, Redpath A, Macintyre IM. Changing pattern of admission and operation for duodenal ulcer in Scotland. Br J Surg. 1994;81:87–9.

19. Sonnenberg A, Fritsch A. Changing mortality of peptic ulcer disease in Germany. Gastroenterology. 1983;84:1553–7.

20. Higham J, Kang J-Y, Majeed A. Recent trends in admissions and mortality due to peptic ulcer in England: increasing frequency of haemorrhage among older subjects. Gut. 2002;50:460–4.

21. Langman MJ, Weil J, Wainwright P, Lawson DH, Rawlins MD, Logan RF et al. Risks of bleeding peptic ulcer associated with individual non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Lancet. 1994;343:1075–8.

22. Dowell SF, Ho MS. Seasonality of infectious diseases and severe acute respiratory syndrome-what we don’t know can hurt us. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4:704–8.

23. Nelson RJ. Seasonal immune function and sickness responses. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:187–92.

24. Beggs PJ. Impacts of climate change on aeroallergens: past and future. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:1507–13.