48uep6bbphidvals|159

48uep6bbphidcol4|ID

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Amyloidosis is a rare and unique metabolic storage disease that results from deposition of insoluble fibrillar protein or aberrantly folded and assembled protein fragments in a variety of organs and tissues. Although gastrointestinal involvement is common, clinical manifestations are highly variable and it rarely causes severe symptoms. (1) Malabsorption as the initial presentation of primary amyloidosis is very rare. (2,3) Moreover, amyloidosis selectively involving the small bowel is also very unusual. (4,5,6 ) We report a rare case of selective amyloid deposition in the small bowel presenting as chronic diarrhoea and malabsorption.

Case Report

A 51-year-old woman presented with large volume diarrhoea of 6 months duration. There was history of progressive anorexia and weight loss of approximately 10 kg. There was no history of passage of blood or mucus per rectum, abdominal pain, gastrointestinal bleeding, constipation, bone pain, dyspnoea or fever. The patient had never suffered tuberculosis, rheumatoid arthritis, hepatitis, diabetes mellitus, or collagen-vascular disease and her family history was insignificant.

On examination she was pale, malnourished, with blackish pigmentation of lips and extremities and bilateral pedal oedema. Her abdomen was soft, non-tender, and without palpable mass or hepatosplenomegaly. Examination of other organ systems was unremarkable. Laboratory findings on admission included the following: haemoglobin 8.5 g/dl, total white cell count 7800/mm3, platelet count 190,000/mm3 and peripheral smear suggestive of megaloblastic anaemia. Other abnormal biochemical test results included total serum protein 4.5 g/dl, albumin 1.9 g/dl, vitamin B12 level 146 pg/ml and folate 3.1 ng/ml. The prothrombin time was prolonged but other routine biochemical tests were within normal range. Urinalysis did not reveal proteinuria. Stool examination did not reveal parasite or occult blood but was positive for Sudan fat stain. Chest and abdominal radiograph and electrocardiogram were normal. Ultrasonography of the abdomen revealed minimal free fluid but was otherwise normal. Ascitic fluid analysis revealed 30 cells/mm3 (all lymphocytes), protein 1.4 g/dl, albumin 0.8 g/dl and adenosine deaminase 4.0 IU/L. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and colonoscopy with ileoscopy were normal. CT scan of the abdomen showed minimal thickening of the small bowel with interloop ascites. Barium meal follow-through examination revealed coarse mucosal pattern and thickening of folds involving the jejunum and proximal ileum. Push enteroscopy revealed a fine granular appearance and thickened and oedematous mucosal folds (Figure 1). Histopathologic evaluation revealed extracellular, eosinophilic, amorphous material suggesting amyloid deposits confirmed by Congo Red staining (Figure 2). There was marked amyloid deposition in the submucosal and muscle layers and in the walls of the medium and small vessels. Serum and urine protein electrophoresis revealed no abnormality. The bone marrow finding was nondiagnostic. Echocardiography was normal. Therapy was directed at symptomatic control of the gastrointestinal manifestations.

.jpg)

Fig. 1: Enteroscopic view showing thickened and oedematous mucosal folds of the

jejunum.

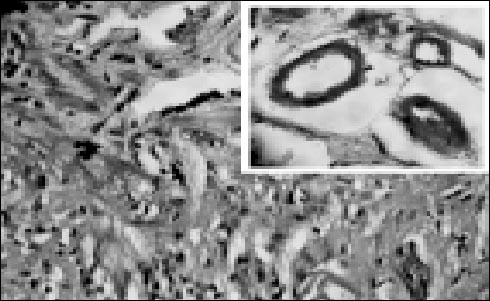

Fig. 2: Photomicrograph depicting abundant amorphous eosinophilic material within

the jejunal mucosa and submucosa (haematoxylin-eosin, original magnification × 40).

Inset: Congo Red positive amyloid deposits in and around wall of blood vessels (Congo

Red, original magnification × 100)

Discussion

Systemic amyloidosis is not a single disease but results from a variety of different diseases. Primary (AL) amyloidosis most commonly occurs in the setting of plasma cell or B cell dyscrasias or monoclonal gammopathies. Secondary (AA) amyloidosis occurs in the setting of chronic inflammatory or infectious conditions. Systemic amyloidosis affects every part of the gastrointestinal tract from the mouth to the anus. Gastrointestinal tract dysfunction in amyloidosis can result from direct mucosal infiltration or from dysmotility caused by autonomic failure. Although it usually does not cause symptoms, GI involvement may manifest as malabsorption, motility disorder, pseudotumour, intestinal perforation, or gastrointestinal bleed. (2,3,7,8,9,10 ) It also causes pancreatic and hepatic disease. ( 7,11 ) Gastrointestinal involvement appears to be less common in AL amyloidosis, with biopsy diagnosed and clinically apparent disease occurring in only 8% and 1%, respectively, of 769 patients in a retrospective review from the Mayo Clinic. (12) Mlabsorption and steatorrhoea are present in fewer than 5% of patients with primary systemic amyloidosis. (2) The underlying mechanism of malabsorption remain unclear, but may include autonomic neuropathy of the enteric nervous system, myopathy secondary to smooth muscle amyloid infiltration, bacterial overgrowth as a result of dysmotility, and ischemia due to vascular infiltration. (13,14,15,16 ) In one of the largest series that included 19 such patients seen at the Mayo Clinic between 1960 and 1988, the most common clinical features seen were weight loss, diarrhoea, and steatorrhoea .(2) Less common features included anorexia, dizziness, hypotension and orthostatic changes. Various endoscopic findings have been reported: a fine granular appearance, multiple yellowish-white polypoid protrusions, prominent folds, small mucosal haemorrhages, shallow ulcers, erosions, waxy plaques, and mucosal friability. (17,18 ) Endoscopists should be aware of the many possible endoscopic appearances as it may be the only initial manifestation of gastrointestinal amyloidosis in the absence of gastrointestinal symptoms. The definitive diagnosis of amyloidosis must be made by tissue biopsy. The abdominal fat pad aspirate is the easiest way of obtaining tissue. Tissue biopsy of duodenal or colorectal mucosa is more sensitive than fat biopsy. Amyloid can be seen by routine haematoxylin and eosin stains as amorphous eosinophilic material. Congo Red is the best stain; when positive, it demonstrates an apple-green birefringence under polarising light. The biopsy should be deep enough to include the lamina propria since amyloid birefringence is best identified in the wall of blood vessels. Initial evaluation of primary amyloidosis should include serum or urine protein electrophoresis. A bone marrow aspirate and biopsy should be performed to establish plasma cell clonality if suspicion for primary amyloidosis persists despite negative serum and urine protein electrophoresis as one would see in a nonsecretory variant. An intensive search for secondary causes is mandatory. In up to 15% of cases, no apparent underlying cause is found.(19) In our patient there were no predisposing conditions and no other sites of amyloid deposition and a diagnosis of primary amyloidosis isolated to the small bowel was made. Therapy is directed at symptomatic control of the gastrointestinal manifestations and at the underlying cause of amyloidosis if found. The principles of treatment are: restoration of hydration and nutrition, suppression of bacterial overgrowth, use of prokinetic agents, and anti-emetic agents. Diarrhoea can be managed with agents such as loperamide and octreotide. Those who are malnourished or unable to tolerate feeding due to dysmotility may benefit from total parenteral nutrition.(9) Patients with primary amyloidosis may show increased survival by treatment with melphalan and prednisolone.

References

1. Gertz MA, Lacy MQ, Dispenzieri A. Amyloidosis. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1999;13:1211–33.

2. Hayman SR, Lacy MQ, Kyle RA, Gertz MA. Primary systemic amyloidosis: a cause of malabsorption syndrome. Am J Med. 2001;111:535–40.

3. Mishra P, Alexander J, Desai N, Dongre L, Amarapurkar A, Paladugu HK, et al. Intestinal amyloidosis presenting as malabsorption syndrome. Trop Gastroenterol. 2006;27:44–5.

4. Griffel B, Man B, Kraus L. Selective massive amyloidosis of small intestine. Arch Surg. 1975;110:215–7.

5. Hemmer PR, Topazian MD, Gertz MA, Abraham SC. Globular amyloid deposits isolated to the small bowel: a rare association with AL amyloidosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:141–5.

6. Shimizu S, Yoshinaka M, Tada M, Kawamoto K, Inokuchi H, Kawai K. A case of primary amyloidosis confined to the small intestine. Gastroenterol Jpn. 1986;21:513–7.

7. Lovat LB, Pepys MB, Hawkins PN. Amyloid and the gut. Dig Dis. 1997;15:155–71.

8. Kyle RA, Greipp PR. Amyloidosis (AL). Clinical and laboratory features in 229 cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1983;58:665–83.

9. Tada S, Iida M, Yao T, Kitamoto T, Yao T, Fujishima M. Intestinal pseudo-obstruction in patients with amyloidosis: Clinicopathologic differences between chemical types of amyloid protein. Gut 1993;34:1412–7.

10. Chang SS, Lu CL, Tsay SH, Chang FY, Lee SD. Amyloidosis-induced gastrointestinal bleeding in a patient with multiple myeloma. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;32:161–3.

11. Buck FS, Koss MN. Hepatic amyloidosis: morphologic differences between systemic AL and AA types. Hum Pathol. 1991;22:904–7.

12. Menke DM, Kyle RA, Fleming CR, Wolfe JT 3rd, Kurtin PJ, Oldenburg WA. Symptomatic gastric amyloidosis in patients with primary systemic amyloidosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 1993;68:763–7.

13. Ectors NL, Geboes KJ, Rutgeerts PJ. Malabsorption and motor dysfunction in patients with small bowel amyloidosis. Gut. 1994;35:864.

14. Koppelman RN, Stollman NH, Baigorri F, Rogers AI. Acute small bowel pseudo-obstruction due to AL amyloidosis: a case report and literature review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:294–6.

15. Ectors N, Geboes K, Kerremans R, Desmet V, Janssens J. Small bowel amyloidosis, pathology and diagnosis. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 1992;55:228–38.

16. Lee JG, Wilson JA, Gottfried MR. Gastrointestinal manifestations of amyloidosis. South Med J. 1994;87:243–7.

17. Tada S, Iida M, Yao T, Kawakubo K, Yao T, Fuchigami T, et al. Endoscopic features in amyloidosis of the small intestine: clinical and morphologic differences between chemical types of amyloid protein. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:45–50.

18. Tada S, Iida M, Iwashita A, Matsui T, Fuchigami T, Yamamoto T, et al. Endoscopic and biopsy findings of the upper digestive tract in patients with amyloidosis.Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:10–4.

19. Gillmore JD, Lovat LB, Hawkins PN. Amyloidosis and the liver. J Hepatol. 1999;30:17–33.