48uep6bbphidvals|43

48uep6bbphidcol4|ID

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Generalised peritonitis continues to be one of the commonest surgical emergencies in India. Despite many advances in perioperative care, antimicrobial therapy and intensive care support, patients with peritonitis still suffer high morbidity and mortality.(1,2) Many patients present late with pre-established sepsis and septic shock, which are associated with a high mortality rate. The algorithm leading to sepsis and multi-organ failure has also been worked out in much detail, but no medical agent has proven useful in reversing this cascade in clinical trials.(3,4) Despite the high incidence of peritonitis in our country, data is still relatively scarce, more so in the previous 10 years. The present study explored the aetiology and outcome of peritonitis in our hospital, and compared the results obtained with those from previous data.

METHODS

A retrospective study of patients treated for peritonitis in a single surgical unit at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Delhi, from January 1995 through September 2006 was done. Peritonitis was defined as the presence of purulent or gastrointestinal contents in the peritoneal cavity at laparotomy. Patients who presented with peritonitis following trauma or those with complications of previous treatment (e.g. an enterocutaneous fistula or an anastomotic dehiscence) were not included in the study.

Patients underwent emergency exploratory laparotomy after adequate preoperative resuscitation. The peritoneal lavage was done with copious amounts of warm saline. The site and cause of peritonitis was identified and treated accordingly. Closure of the abdominal wound or laparostomy was done as per the systemic and local condition of the patient. Single or multiple drains were inserted in all cases. All patients received broad spectrum antibiotics in the peri-operative period.

RESULTS

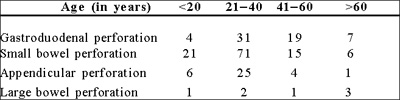

A total of 260 patients operated on for peritonitis were included in the study from January 1995 to September 2006. The mean age of patients was 34.2 years (13-90 years). The male: female ratio was 2:1, 182 male and 78 female. The age distribution of the common causes of peritonitis is shown in Table I.

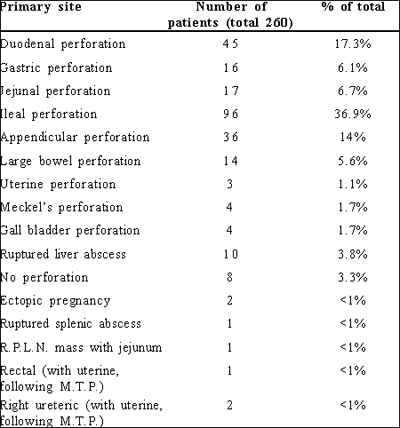

The common sites of perforation were the small bowel in 113 (43%, 96 ileal and 17 jejunal), the stomach or the duodenum in 61 (23%), the appendix in 36 (15%), and, the large bowel in 14 (6%) (Table II). Iatrogenic perforation following medical termination of pregnancy (MTP) was also included here as this procedure is associated with injury to other intra-abdominal organs and the presentation and management is similar to that of non-traumatic peritonitis.

The overall mortality was 26/260 (10%). The major complications encountered were burst abdomen in 29 (11%), anastomotic leak in 13 (5%), intra-abdominal abscess in 20 (8%), and, multi-organ failure in 17 (6.5%) patients. Results pertaining to the individual causes are described below.

Table I: Age distribution of patients with main causes of peritonitis

Figure represents numbers

Table II: Causes of peritonitis

R.P.L.N: Retroperitoneal lymph node;

M.T.P: Medical termination of pregnancy

GASTRIC/DUODENAL PERFORATION

There were 61 patients with perforations of the stomach (16) and duodenum (45). All patients in this group presented with acute epigastric pain, with an average duration of 36 hours. Only 6 patients (10%) presented within 6 hours of the onset of pain. Evidence of pneumoperitoneum on chest or abdominal radiographs was present in 52 (85%) patients. All duodenal perforations were present on the anterior wall of the first part of the duodenum, while most (15/16) of the gastric perforations were present in the antrum. 1 patient had perforation in the body of the stomach at the lesser curve. Graham’s omental patch repair was done in 59 cases and truncal vagotomy and pyloroplasty in one patients. 1 patient with a perforated malignant gastric ulcer underwent a partial gastrectomy. Biopsy of the ulcer edge was taken for all gastric perforations, but rarely in duodenal ulcers where the surgeon only palpated for suspicious induration surrounding the ulcer. Biopsy of the ulcer edge in 26 cases revealed inflammatory pathology in all except 1, where gastric adenocarcinoma was detected.

The mortality rate was 5/61 (8.2%), where 1 had gastric perforation and the rest had duodenal perforation. Major complications were chest infection in 15 (26%), burst abdomen in 7 (11%), and ileus, superficial wound infection, anastomotic leak and postoperative intra-abdominal collection in 6 cases each (10%), and, multi-organ failure in 4 cases (7%). Gastric perforation was associated with more morbidity than was duodenal perforation.

SMALL BOWEL PERFORATION

This was seen in 113 patients (96 ileal and 17 jejunal). Fever was the most common presenting complaint in this group, and prolonged fever (>1 week duration) was present in 46 (40%) cases. Abdominal pain was the next most common symptom, and it was present for an average duration of 4 days (range 6 hours to 10 days). 21 patients had a history of previous episodes of intestinal obstruction and/or intake of antitubercular therapy (ATT). Pneumoperitoneum was identified pre-operatively in 56 cases (50%).

95% of the ileal perforations were present on the antimesenteric border of the terminal ileum. Gangrene of a bowel segment with multiple perforations was present in 8 cases. Widal test for typhoid was positive in 31 of the 49 patients tested on clinical suspicion (63% positive), though blood culture was positive for Salmonella species in only 2 patients.

Primary repair of the perforation was done in 57 cases (49 ileal and 8 jejunal perforations). Resection of the diseased segment of bowel and anastomosis was performed in 23 patients (22 ileal and 1 jejunal perforation). Enterostomy with or without resection of bowel was done in 33 patients (25 ileal and 8 jejunal perforation). The abdominal wall was left open, covered with a plastic sheet (UrobagTM), as a laparostomy in 9 patients to prevent abdominal compartment syndrome. Most of these patients needed postoperative ventilatory support for variable periods. Histopathology of the diseased segment of gut or the ulcer edge revealed tuberculosis in 30 patients, non-specific inflammation in 52, and fibromatosis in 1.

Mortality in ileal perforations was 14/96 (12%), and in jejuna perforations was 4/17 (25%). Major complications were wound infection, ileus, anastomotic leak and intra-abdominal collection (6 patients each), chest infection (15 patients), burst abdomen (7 patients), and multi-organ failure (4 patients).

APPENDICULAR AND CAECAL PERFORATION

There were 36 patients of appendicular perforation and 7 patients of caecal perforation. Of the latter, 6 were associated with appendicitis or appendicular perforation, and 1 was secondary to volvulus. Hence these two groups have been taken together. Pain, for an average duration of 3 days, was the most common symptom. Pneumoperitoneum was seen on radiographs in 11/43 (25%) cases.

Appendicectomy was the only operation required in the majority (39 cases). Limited right colonic resection and anastomosis, and faecal diversion were done in 2 patients each. All specimens, except one, revealed inflammatory pathology on histology. A single appendicectomy specimen revealed carcinoid tumour, localised to the mucosa and hence, was treated completely by the appendicectomy procedure.

There was no mortality in this group. The main complications were wound infection (8 patients), ileus (5 patients), chest infection (4 patients), intra-abdominal collection (2 patients), and, burst abdomen and anastomotic leak (1 patient each).

LARGE BOWEL PERFORATION

There were 14 patients with large bowel perforation. Presentation was late in these patients (average 4 days) and all but 2 required faecal diversion. In 2 patients, resectionanastomosis was done. On histopathological examination.3 patients had malignancy (adenocarcinoma), 5 had tuberculosis, and, 6 had non-specific inflammation. 1 patient died in this group because of septic shock.

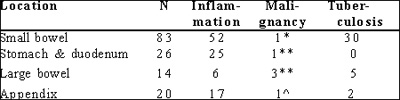

Table III: Histopathology of the main causes of perforation

*Fibromatosis **Adenocarcinoma ^Carcinoid

HISTOPATHOLOGY

Ulcer edge biopsy samples were sent for pathological examination, to diagnose unsuspected tuberculosis or cancer. As seen in Table III, malignant perforations do account for some cases, more commonly in the large bowel. As expected, tuberculosis was more frequent in the small bowel (30 cases). It is interesting to note, that, of the 8 cases where no perforation was seen at laparotomy, omental or peritoneal biopsy revealed tuberculosis in 5 cases. Limitations of data collection included an inability to trace some of the histopathology reports and deterioration of certain specimens

PERITONITIS- THEN AND NOW

Data acquired from a similar study conducted by our unit in the previous decade (1985 to 1995) was compared with that obtained from the present study (Tables IV). There was remarkable similarity in the total number of patients, their demographic profile and even in the overall mortality. The male:female ratio however was significantly different, a drop from 6:1 to 2:1. This could partly be explained by the relative decrease in the proportion of gastric perforation, an entity more common in men. But the magnitude of change in the gender ratio could not faithfully be accounted for. Though small bowel perforation was still the most common cause of peritonitis, there was a decline in the number of gastro-duodenal perforations (32% to 23%), presumably because of ever-improving medical treatment of the acid peptic disease.

Other important differences were the performance of enterostomy and laparostomy in the management of small bowel perforations. As compared to the previous decade, where no stoma or laparostomy was performed, there were 41 enterostomies and 9 laparostomies in the present group. Although the leak rate decreased from 13% to 4%, there was no change in mortality in cases of small bowel perforation.

For treatment of gastro-duodenal perforations, primary repair was the main modality in both studies. But there was increase in both mortality (4% vs. 8%) and leak rates (4% vs. 10%). This was perhaps due to the slightly higher proportion of gastric perforations, which tended towards greater morbidity.

DISCUSSION

Generalised peritonitis, mostly secondary, is still a significant surgical problem in tropical countries like India. It has comprised more than 25% of emergency operations in our hospital over the last three decades.(5,6) The scenario is perhaps similar to that seen in most other hospitals in the country. But data are relatively scarce for this very common problem. In most cases patients present to the hospital in late stages with established peritonitis and sepsis. This contributes significant burden to our medical services and loss to society, as most of the affected patients are young individuals in the prime of their life.

Table IV: Peritonitis- then and now: comparison of demographic parameters

It is well known that perforations of the large bowel constitute a higher proportion of peritonitis cases in developed countries than in developing countries like India.(7, 8, 9) This was confirmed by our study. Various factors, like lower incidence of infectious diseases, especially typhoid and tuberculosis, and, higher incidence of inflammatory colitis, like Crohn’s disease and diverticulitis, in these countries contribute to this fact.

Gastro-duodenal perforation constitutes the most common cause of peritonitis in most studies from the Eastern hemisphere, ranging from 25% to 81%.(9,10,11,12,13) Our data is consistent with previous Indian studies, which showed that small bowel perforations outnumbered other causes, ranging from 36% to 41%.(5,6,14) In our hospital, the proportion of gastro-duodenal perforations has also decreased in the last decade (32% to 23%), whereas that of small bowel perforations has increased slightly (41% to 43%). This may be due to the increase in the number of female patients (34/250 to 78/260), as gastro-duodenal perforations are more common in the male population.

Duodenal ulcer perforation is more common than gastric perforation (ulcer or malignancy) all over the world, the ratio ranging from 4:1 to 20:1(5,6,7,15,16,17,18,19) This was also reflected in our data, but the ratio (3:1) was lower than that seen in our previous data and published literature. The mortality of gastroduodenal perforations in our series was 8%. Though higher than our previous records (vide supra), this is comparable to others’ similar experiences (3%- 11%).(5,6,7,15,16,17,18,19)

Overall, one can say that advances in the medical measures for acid peptic disease have reduced the number of elective operations, and to a lesser extent emergency operations for complications. Mortality from the latter is still high, even in higher centres. A more significant advantage of better medical therapy is reduction in the number of definitive acid-reducing procedures performed during emergency operations. Primary repair has been effective for most types of duodenal and gastric perforations (not malignant).(20, 21) This reduces operating time and can be easily performed by resident doctors.

In India, the small bowel is the most common site of spontaneous perforation as shown in our study. Most perforations occur in the distal ileum. This is because the two main causes, namely enteric fever and tuberculosis are prevalent in this region. In our study, 14% of small bowel perforations were jejunal; 60% of jejunal perforations were tubercular, and the morbidity and mortality (25%) of these lesions was higher. This subset has not been identified in earlier studies. Pneumoperitoneum has been observed in 50%-80% in various series, and was 50% in our case.(5,22,23,24)

The diagnosis of typhoid perforation was made by a combination of clinical, serological (Widal), and, microbiological (blood culture) parameters. Histology revealed non-specific inflammation in most cases at our institute. Widal positivity of our study compares with other Indian data. It has also been shown earlier that non-typhoid and typhoid ileal perforations are similar in presentation and prognosis.(5,22,25)

Abdominal tuberculosis was another common cause in our series. Most cases had either prior episodes of obstruction, or a history of anti-tubercular drug intake, or the operative finding of a stricture proximal to the perforation. But perforation in tuberculosis can occur without stricture formation,(26,27) as seen in about 10% of our patients.

Damage-control measures at operation, like the creation of stoma and laparostomy, have been widely accepted in preventing mortality and morbidity. ‘Abdominal compartment syndrome’, and its deleterious effects, is also being increasingly recognised. We have been very liberal in performing these procedures, especially over the last 5 years, but mortality due to small bowel perforation still remains high.

Appendicular perforation is common in our experience (~15%). Previous series have reported a frequency of 11% to 33%. The favourable prognosis of this condition is well documented. (5,6,10,11,16) Hepatobiliary perforations (ruptured gall bladder or liver abscess) are uncommon, but carry high mortality.(28,29,30) Large bowel perforation is less frequently seen in our country.

In conclusion, peritonitis remains a significant surgical problem associated with high morbidity and mortality. Small bowel perforation as the commonest form of perforation and mortality associated with peritonitis has not changed over the years.

REFERENCES

1. Solomkin JS, Wittman DW, West MA, Barie PS. Intraabdominal infections; in Principles of Surgery. Schwartz SI, Shires GT, Spencer FC et al. Ed. 7th Edition. McGraw Hill, New York, USA. 1999;2:1515–51.

2. Gupta S, Kaushik R. Peritonitis- the Eastern experience. World J Emerg Surg. 2006;1:13.

3. Ben- Baruch A, Michiel DF, Oppenheim JJ. Signals and receptors involved in recruitment of inflammatory cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:11703–6.

4. Dinarello CA. The proinflammatory cytokines interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor and treatment of the septic shock syndrome. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:1177–84.

5. Dorairajan LN, Gupta S, Deo SVS, Chumber S, Sharma LK. Peritonitis in India- a decade’s experience. Trop Gastroenterol. 1995;16:33– 8.

6. Sharma L, Gupta S, Soin AS, Sikora S, Kapoor V. Generalized peritonitis in India- the tropical spectrum. Jpn J Surg. 1991;21:272– 7.

7. Crawford E, Ellis H. Generalised peritonitis- the changing spectrum. A report of 100 consecutive cases. Brit J Clin Pract. 1985;39:177– 8.

8. Washington BC, Villalba MR, Lauter CB, Colville J, Starnes R. Cefamandole-erythromycin-heparin peritoneal irrigation. An adjunct to the surgical treatment of diffuse bacterial peritonitis. Surgery. 1983;94:576–81.

9. Nishida T, Fujita N, Megawa T, Nakahara M, Nakao K. Postoperative hyperbilirubinemia after surgery for gastrointestinal perforation. Surg Today. 2002;32:679–84.

10. Qureshi AM, Zafar A, Saeed K, Quddus A. Predictive power of Mannheim Peritonitis Index. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2005;15:693–6.

11. Chen SC, Lin FY, Hsieh YS, Chen WJ. Accuracy of ultrasonography in the diagnosis of peritonitis compared with the clinical impression of the surgeon. Arch Surg. 2000;135:170–4.

12. Dandapat MC, Mukherjee LM, Mishra SB, Howlader PC. Gastrointestinal perforations. Indian J Surg. 1991;53:189–93.

13. Shah HK, Trivedi VD. Peritonitis- a study of 110 cases. Indian Practitioner. 1988;41:855–60.

14. Tripathi MD, Nagar AM, Srivastava RD, Partap VK. Peritonitisstudy of factors contributing to mortality. Indian J Surg. 1993;55:342–9.

15. Peoples JB. Candida and perforated peptic ulcers. Surgery. 1986;100:758–64.

16. Khan S, Khan IU, Aslam S, Haque A. Retrospective analysis of abdominal surgeries at Nepalgunj Medical College, Nepalgunj, Nepal: 2 year’s experience. Kathmandu University Medical Journal. 2004;2:336–43.

17. Siu WT, Leong HT, Law BK, Chau CH, Li AC, Fung KH, et al. Laparoscopic repair for perforated peptic ulcer: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2002;235:313–9.

18. Chan WH, Wong WK, Khin LW, Soo KC. Adverse operative risk factors for perforated peptic ulcer. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2000;29:164–7.

19. Sugimo o K, Hirata M, Takishima T, Ohwada T, Shimazu S, Kakita A. Mechanically assisted intraoperative peritoneal lavage for generalized peritonitis as a result of perforation of the upper part of the gastrointestinal tract. J Am Coll Surg. 1994;179:443–8.

20. Gupta S, Kaushik R, Sharma R, Attri A. The management of large perforations of duodenal ulcers. BMC Surg. 2005;5:15.

21. Sharma D, Saxena A, Rahman H, Raina VK, Kapoor JP. ‘Free omental plug’: a nostalgic look at an old and dependable technique for giant peptic perforations. Dig Surg. 2000;17:216–8.

22. Chatterjee H, Jagdish S, Pai D, Satish N, Jayadev D, Reddy PS. Changing trends in outcome of typhoid ileal perforations over three decades in Pondicherry. Trop Gastroenterol. 2001;22:155– 8.

23. Kayabali I, Gökçora IH, Kayabali M. A contemporary evaluation of enteric perforation in typhoid fever. Int Surg. 1990;75:96–100.

24. Keenan JP, Hadley GP. The surgical management of typhoid perforation in children. Br J Surg. 1984;71:928–9.

25. Chatterjee H, Pai D, Jagdish S, Satish N, Jayadev D, Srikanthreddy P. Pattern of nontyphoid ileal perforation over three decades in Pondicherry. Trop Gastroenterol. 2003;24:144–7.

26. Shah S, Thomas V, Matan M, Chacko A, Chandy G, Ramakrishna BS, et al. Colonoscopic study of 50 patients with colonic tuberculosis. Gut. 1992;33:347–51.

27. Chen YM, Lee PY, Perng RP. Abdominal tuberculosis in Taiwan: a report from Veterans’ General Hospital, Taipei. Tuber Lung Dis. 1995;76:35–8.

28. Lygidakis NJ. Risk factors in peritonitis. Brit J Clin Pract. 1986;40:181–6.

29. Sarda AK, Bal S, Sharma AK, Kapur MM. Intra peritoneal rupture of amoebic liver abscess. Br J Surg.1989;76:202–3.

30. Lee KT, Wong SR, Sheen PC. Pyogenic liver abscess: an audit of 10 years’ experience and analysis of risk factors. Dig Surg. 2001;18:459– 65.