|

Krishna Ravula Phani1, GV Rao1, Naresh Bhat2, Adarsh Chaudhary3, Deepak Govil4

Asian Institute of Gastroenterology,

Hyderabad1,

St Philomena’s Hospital, Bangalore2,

Medanta Hospital Gurgaon3,

Indraprastha Apollo Hospital,

New Delhi4

Corresponding Author:

Dr. G.V. Rao

Email: gvraoaig@gmail.com

48uep6bbphidvals|742 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext The medical therapy of ulcerative colitis (UC) has improved significantly allowing many patients to defer or avoid surgery. Despite this about 25% of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) complicated by acute colitis undergo emergency colectomy.[1] Emergency colectomy is needed in acute severe colitis unresponsive to medical management and for life threatening complications like toxic megacolon, perforation and severe hemmorhage. Most important predictive factor for postoperative morbidity and mortality after colectomy is the timing of surgery.[2] Prolonged unsuccessful medical treatment will delay surgery and increase the risk of postoperative complications in these seriously ill, immunocompromised, malnourished, and deteriorating patients.

Surgery for acute severe colitis unresponsive to medical management Acute severe ulcerative colitis is a medical emergency. It is best defined by the Truelove and Witts’ criteria (ulcerative colitis patients with 6 bloody stools/day and signs of systemic toxicity (heart rate >90/min, body temperature >37.8°C, hemoglobin <10.5 g/dL or ESR >30 mm).[3] The most common indication for urgent surgery is failure of medical management during acute episodes of colitis. Intravenous corticosteroids remain the mainstay of conventional therapy. It is essential that therapeutic alternatives like cyclosporin, tacrolimus and infliximab for rescue of steroid-refractory disease are considered early, on or around day 3 of steroid therapy. Intravenous steroids are generally given till day 5, with no additional benefit beyond day 7.[4]

Recommendations

The response to intravenous steroids is best assessed objectively around the third day [EL2b, RGB]. Treatment options like colectomy should be discussed with patients not responding to intravenous steroids. Second line therapy with either cyclosporin [EL1b, RG B], infliximab [EL1b, RG B] or tacrolimus [EL4, RG C] may be appropriate. If there is no improvement within 4–7 days of salvage therapy, colectomy is recommended [EL4, RG C] (ECCO guidelines).[5]

Predicting need for surgery

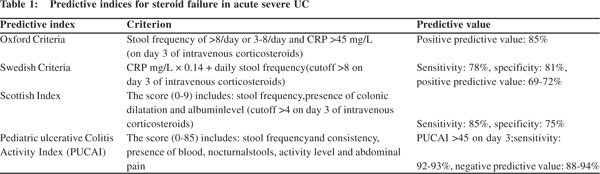

The key challenge in acute colitis remains early identification of patients who are likely fail steroid or alternate salvage therapy and require colectomy. Several clinical indices have proven to perform well in predicting patients who will require salvage therapy within 3-5 days of admission. In a prospective study, Travis et al[6] from Oxford suggested that a stool frequency of >8/day or 3-8/day and C-reactive protein (CRP) >45 mg/dL on the third day of corticosteroid therapy should be sufficient for initiating rescue therapy. Similar to the Oxford criteria several other including the Swedish Index, the Scottish Index and the PUCAI Index for pediatric patients (Table 1) are based on stool frequency, blood in stools, CRP, and colonic dilatation. These indices are based on the consistent observation that the likelihood of responding to corticosteroids is inversely related to the disease severity. Radiological criteria can also be used. Presence of >5.5 cm colonic dilatation or presence of mucosal islands predict need for surgery in 75% of the patients.[7]

Surgery for complications of acute severe colitis

Toxic dilatation (megacolon) is defined as total or segmental non-obstructive dilatation of the colon e”5.5 cm and associated with systemic toxicity. Although its true incidence has not been reported, approximately 5% of admitted patients with acute, severe colitis will have toxic dilatation.[8] Risk factors include hypokalaemia, hypomagnesaemia, bowel preparation, and the use of anti-diarrhoeal therapy.8 Early diagnosis of severe colitis, more intensive medical management and early surgery have reduced the incidence and mortality of toxic megacolon complicating UC. Surgery is usually the preferred therapeutic option in patients with toxic megacolon, which is a life threatening event. However, a 24-48 hour trial of conservative treatment in form of bowel rest, broad spectrum antibiotics and rectal tube, may be cautiously attempted in non-severe cases at specialized centres, only under intense monitoring.[9] Colonic perforation occurs in the setting of toxic megacolon and is an indication for urgent surgery. Perforation is the most serious complication of acute severe colitis and is often associated with inappropriate total colonoscopy or toxic dilatation where colectomy has been inappropriately delayed. It carries a mortality of up to 50%.[8] Signs and symptoms may be masked by corticosteroids and a high index of suspicion is needed in patients on medical management. Urgent subtotal colectomy with ileostomy is needed in patients once diagnosis is confirmed by X-rays or CT scan. Massive hemmorhage is a very rare indication for urgent colectomy in ulcerative colitis.

Improvements in medical management of ulcerative colitis and an early aggressive surgical approach have reduced the incidence of life threatening complications like toxic megacolon, perforation and hemmorhage. In a review of publications from 1975 to 2007, indications for surgery included failure of medical therapy in 44.2%, toxic megacolon in 42.2%, hemorrhage in 7.7%, and perforation in 7.0%. The indications for surgery have changed over time. The incidence of toxic megacolon has decreased from 71.1% in the first decade to 21.6% in the third decade.[10]

Type of surgery

A staged proctocolectomy (subtotal colectomy first) with preservation of rectum and Brookes ileostomy is widely accepted to be the first wise step in the surgical treatment of acute severe colitis or if patients are saturated with corticosteroids. This approach has several advantages: 1) colectomy with an ileostomy will cure the patient of colitis, and allow him/her to regain general health, normal nutrition and give the patient time to carefully consider between the option of an IPAA or a permanent ileostomy; 2) a preliminary subtotal colectomy helps clarify the pathology and excludes Crohn’s disease. In ~15% of colitis patients it is impossible to clinically differentiation between Crohn’s disease and UC and they are deemed to have indeterminate colitis. Even in patients undergoing ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA) for confirmed UC 2.5-3.5% of the patients are ultimately found to be suffering from Crohn’s disease.[11]; 3) avoiding a proctectomy simplifies the operation and preserves the rectal planes making subsequent surgery and IPAA reconstruction more straightforward; and 4) subtotal colectomy is a relatively safe procedure even in the critically ill patient if the appropriate expertise is available. There is emerging evidence that it is safe to perform minimally invasive or laparoscopic surgery.[12,13] When performing this first stage surgery it is recommended to preserve the ileocolic vessel at its most distal extent in order to facilitate adequate length for a subsequent small intestinal pouch.

Although many surgeons performing pouch reconstruction routinely divide the ileocolic, the most conservative approach would be its preservation.

Restorative proctocolectomy in acute severe colitis Several centres caring for a high volume of UC patients have reported their results of restorative proctocolectomy in individuals undergoing urgent or emergent surgery. Some have reported good results. Harms et al reported a series of IPAA in 20 patients with fulminant colitis. Their average serum albumin was 2.1 mg/dl and prednisone dose was 58 mg/day. The anastomotic leak rate was 5% and overall day and night continence was similar to patients undergoing elective surgery.[14] Ziv and coworkers performed IPAA on patients with moderate fulminant colitis, excluding patients with hemodynamic changes and megacolon but no significant pelvic sepsis.[15] Creating a pouch in the acutely ill patient has two major drawbacks. First, as described earlier, the diagnosis of UC may be incorrect, especially in cases of fulminant colitis. Second, there is evidence that performing an IPAA on a patient taking high-dose corticosteroids is associated with more complications. Specifically, pelvic sepsis and anastomotic leaks may be more frequent. This presents problems not only in the early postoperative period, but the incidence of poor pouch function and pouch failure may be higher in this population.[16]

Clearly this is an aggressive technique that should be considered only by the most experienced surgeons. In summary, construction of the pouch should be avoided in acute settings because of a high risk of pelvic bleeding, sepsis and injury to pelvic nerves. After the patient has fully recovered, a restorative operation with construction of the ileal-pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA) and ileostomy closure can be carried out with a reduced risk of complications.

Guidelines ECCO statement 7A

Delay in appropriate surgery is associated with an increased risk of surgical complications [EL4, RG C]. A staged procedure (colectomy first) is recommended in the acute case when patients do not respond to medical therapy [EL 4, RG C], or if a patient has been taking 20 mg daily or more of prednisolone for more than 6 weeks [EL 4, RG C]. If the appropriate laparoscopic skills are available, a minimally invasive approach is feasible and may confer some advantages [EL4, RG C] (Table 2).

Management of the rectal stump

Length of the rectal stump: long vs. short

The fate of the rectal stump has been of concern both because potential risk of leaving residual disease and the possibility of stump blow out. Regarding the first issue, continued disease activity that cannot be controlled with topical agents is very unusual. Leaving as little rectum as possible (i.e. dividing the middle rectum within the pelvis) is not recommended, because it renders subsequent proctectomy difficult, with a high risk of pelvic nerve injury. Stump blowout refers to pelvic sepsis that may occur with the breakdown of the rectal remnant when left intraperitoneally. The rectal stump is usually thickened and friable and carries the risk of perforation because of ongoing proctitis. The incidence of rectal stump blowout varies in the literature, but can be as high as 12%.[17-19] According to some authors, the incidence of stump blowout is highest in patients with a short stump. Trickett et al report pelvic sepsis in 33% patients if a short intra-pelvic stump was created, 6–12% in patients with an intra-peritoneal stump, and in 3–4% of patients with a mucous fistula.[20]

Options for management of rectal stump

There are several options for management of the rectal stump: 1) divide the rectum at the level of the promontory i.e. at the proper rectosigmoid junction; or 2) leave additional distal sigmoid colon with rectal stump as a mucus fistula attached to anterior abdominal wall. The latter option is considered very safe because no closed bowel is left within the abdomen, but the mucous fistula burdens the patient with another stoma which is not easy to manage. Closing the stump and leaving it within the subcutaneous fat is equally safe, although the skin is probably best left to heal through secondary intention in order to avoid wound infection. There are no studies which have examined the risk of subsequent inflammation or bleeding after leaving varying lengths of rectum or rectosigmoid colon.

Carter and colleagues found that pelvic dissection was subjectively easier with these techniques than with intraperitoneal closure and there was lesser pelvic sepsis.[19] When the rectum is transected within the abdominal cavity at the level of the promontory, transanal rectal drainage is advised for some days, to prevent blowout of the rectal stump due to mucous retention.

Guidelines ECCO statement 7B

When performing a colectomy for ulcerative colitis in emergency circumstances, the whole rectum and the inferior mesenteric artery should be preserved. This facilitates subsequent pouch surgery [EL 4, RG C]. Whether to preserve additional rectosigmoid colon and how to deal with bowel closure is left to the

surgeon’s decision [EL 4, RG C].

Morbidity and mortality after emergency colectomy for acute UC

Colectomy for acute severe colitis is associated with high morbidity as most patients are acutely ill in, chronically malnourished and immunosupressed. But with the emerging trend of early colectomy in non-responders and improved ICU and nutritional support results are progressively improving. Teeuwen et al[10]systematically reviewed the morbidity and mortality in 1,257 patients included from 29 studies conducted over the past three decades. Overall morbidity was 50.8%. The morbidity significantly decreased over the three decades from 62.3% in the first decade to 40.1% in the last decade. Most frequent surgical complications were wound infection/dehiscence (18.4%), intra-abdominal abscess (9.2%), small bowel obstruction (6.2%), ileostomy-related complications (5.5%), and hemorrhage (4.6%). Mortality decreased significantly over time from 10.0% in the first decade to 1.8% in the last. Several large series in the past decade have reported zero mortality with emergency colectomy for acute UC.[21,22,23]

Role of laparoscopy

A comparison between conventional open colectomy and laparoscopic colectomy is difficult due to insufficient data. Laparoscopic colectomy seems to be safe and feasible in inflammatory bowel disease. Possible advantages compared to open surgery include reduced incidence of surgical site infections, incisional hernias, and better cosmesis. The laparoscopic approach probably results in fewer adhesions and lower risk of subsequent small bowel obstruction. Subsequent restorative procedures are not jeopardized by laparoscopic surgery. Marceau et al reported a case control study comparing 40 patients undergoing laparoscopic colectomy with 48 controls who underwent open colectomy.[13]

No mortality was seen in either group. The operation time, morbidity and hospital stay were also comparable in both groups. 84% of patients in the laparoscopic group underwent a subsequent restorative procedure. Several other groups have reported comparable results with laparoscopic emergency colectomy and subsequent restoration surgery.[10,24,25] However, a couple of comments merit consideration. First, the population described in these studies is not uniform. In some studies patients with tachycardia, fever, marked leucocytosis and peritonitis were excluded. Furthermore, laparoscopic colectomy in IBD is technically demanding duo to thickened and friable bowel and mesentery. Based on current evidence it is justified to continue the development of laparoscopic surgery for IBD, but it should be performed by experienced surgeons only.[25]

Guideline

If the appropriate laparoscopic skills are available, a minimally invasive approach is feasible and may confer some advantages [EL4, RG C] (Table 2).

References

- Leijonmarck CE, Persson PG, Hellers G. Factors affecting colectomy rate in ulcerative colitis: an epidemiologic study. Gut. 1990;31:329–33.

- Randall J, Singh B, Warren BF, Travis SP, Mortensen NJ, George BD. Delayed surgery for acute severe colitis is associated with increased risk of postoperative complications. Br J Surg. 2010;97:404–9.

- Truelove SC. Medical management of ulcerative colitis and indications for colectomy. World J Surg. 1988;12:142–7.

- Turner D, Walsh CM, Steinhart AH, Griffiths AM. Response to corticosteroids in severe ulcerative colitis: a systematic review of the literature and a meta-regression. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:103–10.

- Dignass A, Lindsay JO, Sturm A, Windsor A, Colombel JF, Allez M, et al. Second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis part 2: current management. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:991–1030.

- Travis SP, Farrant JM, Ricketts C, Nolan DJ, Mortensen NM, Kettlewell MG, et al. Predicting outcome in severe ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1996;38:905–10.

- Lennard-Jones JE, Ritchie JK, Hilder W, Spicer CC. Assessment of severity in colitis: a preliminary study. Gut. 1975;16:579–84.

- Gan SI, Beck PL. A new look at toxic megacolon: an update and review of incidence, etiology, pathogenesis, and management. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2363–71.

- Mowat C, Cole A, Windsor A, Ahmad T, Arnott I, Driscoll R, et al. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2011;60:571–607.

- Teeuwen PH, Stommel MW, Bremers AJ, van der Wilt GJ, de Jong DJ, Bleichrodt RP. Colectomy in patients with acute colitis: a systematic review. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:676–86.

- Price AB. Overlap in the spectrum of non-specific inflammatory bowel disease—’colitis indeterminate’. J Clin Pathol. 1978;31:567–77.

- Holubar SD, Larson DW, Dozois EJ, Pattana-Arun J, Pemberton JH, Cima RR. Minimally invasive subtotal colectomy and ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for fulminant ulcerative colitis: a reasonable approach? Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:187–92.

- Marceau C, Alves A, Ouaissi M, Bouhnik Y, Valleur P, Panis Y. Laparoscopic subtotal colectomy for acute or severe colitis complicating inflammatory bowel disease: a case-matched study in 88 patients. Surgery. 2007;141:640–4.

- Harms BA, Myers GA, Rosenfeld DJ, Starling JR. Management of fulminant ulcerative colitis by primary restorative proctocolectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:971–8.

- Ziv Y, Fazio VW, Church JM, Milsom JW, Schroeder TK. Safety of urgent restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for fulminant colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:345–9.

- Tulchinsky H, Hawley PR, Nicholls J. Long-term failure after restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. Ann Surg. 2003;238:229–34.

- Ozuner G, Strong SA, Fazio VW. Effect of rectosigmoid stump length on restorative proctocolectomy after subtotal colectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:1039–42.

- Wojdemann M, Wettergren A, Hartvigsen A, Myrhoj T, Svendsen LB, Bulow S. Closure of rectal stump after colectomy for acute colitis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1995;10:197–9.

- Carter FM, McLeod RS, Cohen Z. Subtotal colectomy for ulcerative colitis: complications related to the rectal remnant. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:1005–9.

- Trickett JP, Tilney HS, Gudgeon AM, Mellor SG, Edwards DP. Management of the rectal stump after emergency sub-total colectomy: which surgical option is associated with the lowest morbidity? Colorectal Dis. 2005;7:519–22.

- Teeuwen PH, Stommel MW, Bremers AJ, van der Wilt GJ, de Jong DJ, Bleichrodt RP. Colectomy in patients with acute colitis: a systematic review. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:676–86.

- Hyman NH, Cataldo P, Osler T. Urgent subtotal colectomy for severe inflammatory bowel disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:70–3.

- Hyde GM, Jewell DP, Kettlewell MG, Mortensen NJ. Cyclosporin for severe ulcerative colitis does not increase the rate of perioperative complications. Dis Colon Rectum.2001;44:1436–40.

- Fowkes L, Krishna K, Menon A, Greenslade GL, Dixon AR. Laparoscopic emergency and elective surgery for ulcerative colitis. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:373–8.

- Casillas S, Delaney CP. Laparoscopic surgery for inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Surg. 2005;22:135–42.

|