Everton Cazzo, Jose Antonio Possatto Ferrer, Elinton Adami Chaim

Department of Surgery,

Faculty of Medical Sciences,

State University of Campinas (UNICAMP),

Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Everton Cazzo

Email: evertoncazzo@yahoo.com.br

48uep6bbphidvals|702 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Paracoccidioidomycosis (PCM) is a chronic granulomatous disease caused by Paracoccidioidesbrasiliensis,endemic in Latin America, primarily involving the lungs, but also the skin, mucous membranes, lymph nodes, and internal organs.[1,2,3] Contagion occurs often by inhalation of conidia and mycelial fragments, producing an infection that can spread to other tissues via lymphatic and hematogenous means.[1,2,3,4] We report a rare case of involvement of lymph nodes in the liver hilum by P. brasiliensis.

Case Report

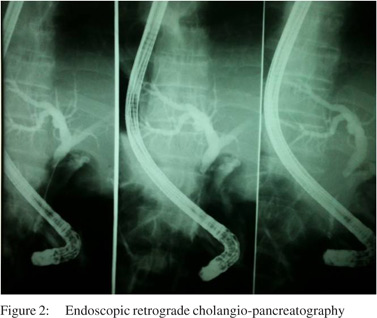

A 56-year-old man, with past history of rural work, between 7 to 18 years of age, presentedwith abdominal pain in the upper right quadrant for 6 months duration, associated with slowly progressive jaundice, choluria and fecal acholia. He also suffereda weight loss of 18 kg in this period. On clinical examination, he wasjaundiced, with tenderness inupperright abdominal quadrant. Laboratory studies revealed high levels of serum transaminases (AST: 148 mg/dL; ALT: 170 mg/dL), canalicular enzymes (ALP: 627 mg/dL; GGT: 750 mg/dL) and bilirubins (direct: 13.4 mg/dL; indirect: 10.7 mg/dL). Abdominal ultrasonography revealed an enlarged liver and dilatation of intra and extra-hepatic biliary ducts. Computed tomography showed a solid and infiltrative lesion of 8.8 cm x 4.5 cm involving the celiac trunk, head and body of pancreas and distal choledocus, whose caliber was increased, and wasassociated withenlarged lymph nodes in the spleen hilum and around the abdominal aorta (Figure 1). Magnetic resonance cholangiography showed the lesioncircumferentially involving medial to distal common biliary duct (Figure 2).The main diagnostic hypothesis was lymphoproliferative disease. An ultrasonography-guided percutaneous biopsy was carried out and revealed a chronic nonspecific inflammatory process. The patient underwent an endoscopic retrogradecholangiopancreatography (ERCP), which showed biliary obstruction from medial to distal choledocus (Figure 3). A stent was placed beyond the obstruction. Biliary Case Reports brushing cytology revealed no neoplastic cells. After 30 days, the patient presented with an episode of acute cholangitis. Wide spectrum antibiotic therapy was carried out and succeeded. Surgical intervention was advised. At laparotomy several enlarged lymph nodes around distal choledocus, involving head and body of pancreas, celiac trunk and portal vessels, and without cleavage plane, was observed. An incisional biopsy of lymph nodes was carried out. A Roux-en- Y hepaticojejunostomy was created. The patient had an uneventful postoperative stayand was discharged from the hospital 5 days after surgery. Hepatic enzyme and bilirubin levels were normal after 14 days. Histological examination revealed a granulomatous caseous process with P. brasiliensis.

Treatment with itraconazole 200 mg daily wasinitiated and lasted 6 months. After 12 months the patient has no clinical or tomographic evidence of disease.

Discussion

PCM is classifiedin acute and subacute or chronic forms. Acute and subacute forms develop from a primary undetected pulmonary lesion that evolves quickly with lymphatic and hematogenous spread to the monocyte-macrophage system. Chronic form is the most commonly seen type in clinical practice and develops from the primary pulmonary complex or from reactivation of a quiescent pulmonary or metastatic focus, after a relatively long duration, and often expressed by pulmonary and tegumental damage.[5] GastrointestinalPCM is rarely recognized because of nonspecific clinical manifestations. It can present as part of a progressive dissemination of infection or as a result of local complications from a silent healing process.[2] Jaundice secondary to PCM may occur as a result of three independent mechanisms: 1) extrinsic compression of biliary ducts due to head of pancreas or liver hilum lymph node

involvement; 2) biliary duct involvement due to granuloma (intrinsic lesion); 3) hepatitis secondary to PCM. The first is the most common mechanism.[2]

References

- Shikanai-Yasuda MA, TellesFilho FQ, Mendes RP, Colombo AL, Moretti ML. Guidelines in paracoccidioidomycosis. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2006;39:297–310.

- Goldani LZ. Gastrointestinal paracoccidioidomycosis: an overview. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:87–91.

- Ramos-e-Silva M, Saraiva LES. Paracoccidioidomycosis. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26:257–69.

- Wanke B, Aidê MA. Chapter 6 - paracoccidioidomycosis. J Bras Pneumol. 2009;35:1245–9.

- Fortes MR, Miot HA, Kurokawa CS, Marques ME, Marques SA. Immunology of paracoccidioidomycosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:516–24.

|