Priyanka Saxena,1 Chhagan Bihari,1 Archana Rastogi,1 Vikrant Sood,2 Rajeev Khanna,2 Seema Alam,2 Shiv Kumar Sarin3

Departments of Hematology and Pathology,1

Pediatric Hepatology,2 and Hepatology3

Institute of Liver and Biliary Sciences,

D-1, Vasant Kunj, New Delhi-110070, India

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Chhagan Bihari

Email: drcbsharma@gmail.com

48uep6bbphidvals|654 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Hemophagocytic lympho histiocytosis (HLH) is a disorder of uncontrolled, pathologic activation of the immune system leading to extreme hyperinflammation. HLH could be familial (due to genetic defects leading to impaired function of natural killer and cytotoxic Tcells) or acquired. Acquired forms of HLH are usually encountered as aresult of viral infections.[1] Acquired HLH due to viral infections (also known as virus associated hemophagocytic syndromeor VAHS) is most commonly associated with Ebstein Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), human herpesvirus type 6 (HHV-6) and HHV-8. Other rarely implicated viruses are human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), adenovirus, coxsackie virus, measles, dengue, rubella, parvovirus B19, herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus.[2]

The presence of persistent high fever, peripheral blood cytopenia (two or more series), hyperferritinemia, hyperlipidemia, hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow (hemophagocytic cell ratio over 3%), splenomegaly and/or lymph nodeenlargement along with active viral infection are required to confirm the diagnosis of VAHS.[3] Despite the high incidence of hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection in pediatric population, HAV induced VAHS has rarely been described in literature.[2] We report a case of 15-year-old male child with hepatitis A virus infection with cholestasis and VAHS.

Case presentation

Clinical history and laboratory findings

A 15-year-old male child was admitted for the first time to the inpatient department of a superspeciality liver institute with symptoms of fever with chills (not associated with rigors). He had associated nausea, vomiting, malaise and loss of appetite. Fever was high grade, continuous and was relieved for only a few hours with antipyretics. The febrileprodrome lasted for one week. On the fifth day of fever, the child developed yellowish discoloration of eyes and high colored urine. Patient was started on oral ciprofloxacin to which he developed hypersensitivity. During the hospital stay he developed rash, severe itching and disturbed sleep. There was no history of mucocutaneous or gastrointestinal bleeding, abdominal distension, pedal edema, clay colored stools, abdominal lump orpain, or loose motions. Laboratory tests showed very high serum bilirubin (direct 17.3mg/dl, indirect 10.7mg/dl) with increased aspartate aminotransferase (AST) at 256IU/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT)at 129IU/L and alkaline phosphatase at 181 IU/L. The blood counts were within normal limits (hemoglobin 14gm/dl, TLC 5.2×109/L, and platelets 257×109/L). The anti-HAV IgM serology was reactive while serology for anti-HEV IgM was non-reactive. The serology for malaria antigen and blood cultures were negative.In view of the high grade fever, cholestaticfeatures,elevated liver enzymes and positive hepatitis A serology, a diagnosis of acute viral hepatitis (hepatitis A) with prolonged cholestasis and presumed cholangitis was made and intravenousmeropenemwas started.

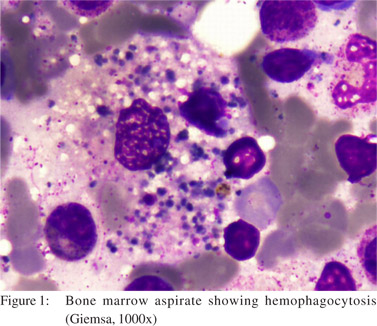

Thereafter, the patient was discharged in a satisfactory conditionafter completing a 10 days course of meropenem, with relevant advice.The patient was readmitted after 15 days with a history of high gradefever (1030C), progressive pallor, fatigue, jaundice and hepatosplenomegaly. Laboratory reports depicted bi-cytopenia with low hemoglobin and total leukocyte count (with neutropenia) but a preserved platelet count (hemoglobin 4.8gm/dl, TLC 2.5×109/L, absolute neutrophil count 0.9×109/L, and peripheral smear normocytic normochromic anemia). Corrected reticulocyte count was also low (0.7%). The patient also had hypertriglyceridemia(690mg/dl), hyperferritinemia(63600µg/L) and normal fibrinogen(269.4mg dl) levels. Lactate dehydrogenase levels were increased (2938 IU/L). Liver function tests were deranged(direct bilirubin 23.6mg/dl, indirect bilirubin 6.7mg/dl, AST 168 IU/L, and ALT 111 IU/L). The serology for CMV, EBV and parvovirus B-19 was negative. Direct Coombs test was negative. Soluble interleukin-2 receptor (sIL-2R) levels were not tested.Four units of packed red blood cells (PRBC) were transfused and bone marrow aspiration and biopsy were carried out. The bone marrow aspiration and biopsy revealed >3% histiocytes showinghemophagocytosis of all three cell lineages.Macrophages were seen with ingested nucleated RBCs, platelets and myeloid precursors (Figure 1).

Treatment

On the basis of clinical and laboratory investigations, the child was diagnosed as hepatitis A withprolonged cholestasis and VAHS. He was instituted onimmunosuppressive therapy with oral prednisolone on tapering dosages (25mg/day daily, followed by decrease of 5mg every two days over a period of 10 days) along with oral cephalosporins for the control of infections. The patient showed immediate clinical and hematological improvement and was discharged in a stable, afebrile state. After one month of therapy, laboratory parameters showed improvement(hemoglobin 9.4gm/dl, TLC 6.9×109/L, absolute neutrophil count 5.1×109/L, ferritin 1950µg/L, LDH 600 IU/L, direct bilirubin 7.3mg/dl, indirect bilirubin 4.5mg/dl, AST 90IU/L, and ALT 110IU/L).

Discussion

Acute hepatitis A is usually a self-limited infection with most patients achieving complete recovery. Hepatitis A can cause cholestatic hepatitis characterized by severejaundice, pruritis, fever, diarrhoea and marked elevations of serum bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase with mild elevation of serum aminotransferases.[4] Our case had most of these features and was initially diagnosed withcholestatic hepatitis A. On readmission the patient was finally diagnosed as hepatitis A with prolonged cholestasis and VAHS,since the patient had developed features of hemophagocytic syndrome. VAHS is a life threatening disorder characterized by secondary HLH with benign histiocytic proliferation, marked hemophagocytosis and evidence of active viral infection.[2]According to the revised diagnostic guidelines for HLH (2004), five out of eight criteria must be met for the diagnosis of hemophagocytic syndrome.[3]Our case met with six criteria out of the eightincluding,fever, splenomegaly, bi-cytopenia, hyperferritinemia, hypertriglyceridemia, andbone marrow hemophagocytosis. In addition, the presence of active hepatitis A viral infection reinforced the diagnosis of VAHS.

Very few cases of HAV related VAHS have been reported in literature. Bay et al in 2012 reported two pediatric cases with HLH secondary to hepatitis A infection.[4] Previous publications are available predominantly from Japan and Taiwan, describing this entity inadult patients. Watanbe et al have reported two adult patients of VAHS secondary to HAV infection who recovered well without any treatment.Previously reports of HAV with VAHS have described leucopenia and bi-cytopenia to be the most common cytopenias. Anemia has rarely been described.[5] Our case had a rare presentation of anemia and leucopenia with a normal platelet count throughout the course of disease. The patient was treated with repeated PRBC transfusions.The presence of anemia in cholestatic hepatitis can be attributed to hemolysis but low reticulocyte counts, a negative Coombs test and the absence of schistocytes on peripheral smear rule out the possibility of hemolysis as the cause of progressive anemia in this patient.Hypertriglyceridemia has also beennoted in viral infections but is usually less than 500mg/dl.[5] This patient had triglyceride levels of 690mg/dl alongwith extremely high levels of serum ferritin (63,600 µg/L) and evidence of hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow which pointed to the diagnosis of HLH.

Immunosuppressive therapy has been tried to control hemophagocytosis with mixed results. Some authors have shown improvement with steroid therapy.[5] Ourpatient responded well to oral prednisolone with eventual correction of anemia and leucopenia. As steroid therapy has also been advocated for cholestaticjaundice, our patient demonstrated clinical and hematological improvement with amelioration of both cholestatic and hemophagocytic symptoms.

Conclusion

HAV related VAHS though rare, is an increasingly recognized disorder in medical literature. Diagnosis of VAHS should be suspected in HAV infected patients with prolonged high grade fever and cytopenias. Bone marrow examination should be carried out wherever necessary. Steroid therapy can be tried in these patients, along with supportive measures.

References

- Janka GE. Familial and acquired hemophagocyticlympho histiocytosis. Annu Rev Med. 2012;63:233–46.

- Ansuini V, Rigante D, Esposito S. Debate around infectiondependent hemophagocytic syndrome in paediatrics. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:15.

- Henter JI, Horne A, Arico M, Egeler RM, Filipovich AH, Imashuku S, et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lympho histiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:124–31.

- Bay A, Bosnak V, Leblebisatan G, Yavuz S, Yilmaz F, Hizli S. Hemophagocyticlymphohistiocytosis in 2 pediatric patients secondary to hepatitis A virus infection. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012;29:211–4.

- Tuon FF, Gomes VS, Amato VS, Graf ME, Fonseca GH, Lazari C, et al. Hemophagocytic syndrome associated with hepatitis A: case report and literature review. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2008;50:123–7.

|