Puneet Chhab offshorera1, Chalapathi Rao2, Harpal Singh2, Vishal Sharma2, Manish Modi3, Mukesh Yadav4, Surinder Singh Rana2, Deepak Kumar Bhasin2, Karter Singh2

Department of Internal Medicine1,

Gastroenterology2, Neurology3, Radiodiagnosis4,

Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research,

Sector 12, Chandigarh-160012,India

Corresponding Author:

Dr Chalapathi Rao A.S

Email: strfwd13@gmail.com

48uep6bbphidvals|614 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext We report two patients of advanced cirrhosis who developed intracranial fungal infections, each of them having variable outcome with the treatment administered.

Case report

Case 1:

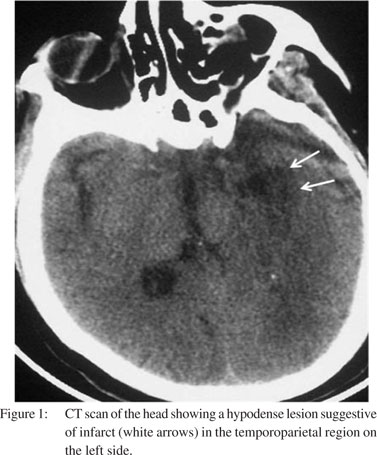

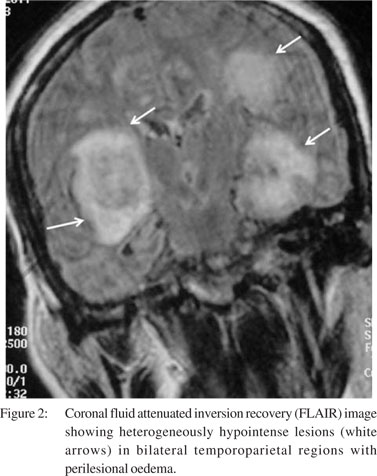

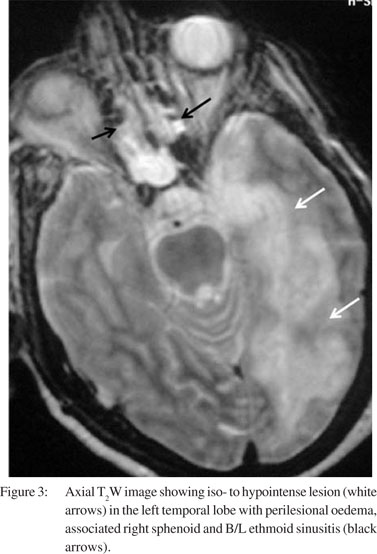

A 40-year-old man with alcoholic liver disease (Child C cirrhosis; Child–Pugh score 12) presented with complaints of fever for one month and altered sensorium for a week. He was in grade IV encephalopathy. Deep tendon reflexes were asymmetrically exaggerated on the right side. He had polymorphonuclear leukocytosis. Liver function tests showed serum bilirubin level of 2.32 mg/dL (0.3–1.3 mg/dL), aspartate transaminase/alanine transaminase (AST/ALT) of 67/47 IU/mL (<40 IU/mL) and alkaline phosphatase level of 96 IU/mL (<128 IU/mL). Serologies for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B and hepatitis C were non-reactive. Blood, urine and tracheal aspirate cultures were sterile. There was no evidence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. He received lactulose and intravenous (IV) broad-spectrum antibiotics (piperacillin/tazobactam and vancomycin). Computerized tomographic (CT) scan of the brain showed multiple hypodense lesions in the left temporo-parietal region (Figure 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain revealed multiple bilateral T2W hypointense lesions with diffusion restriction suggestive of multiple abscesses (Figure 2) and evidence of sinusitis in the form of soft tissue thickening of the paranasal sinuses (Figure 3). Tissue scrapings from the nasal cavity and sinuses showed acutely branched septate hyphae and the cultures grew Aspergillus species. He was started on parenteral voriconazole; however, he did not show improvement and his condition worsened. He received ventilatory support, IV fluids and vasopressors for multiorgan dysfunction. However, the patient could not be salvaged and succumbed to his illness.

Case 2:

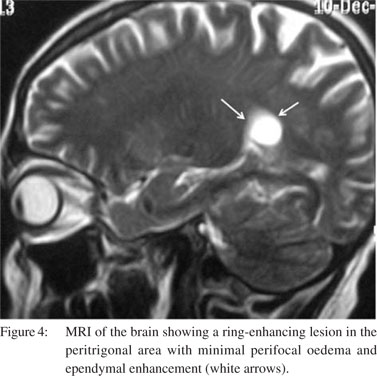

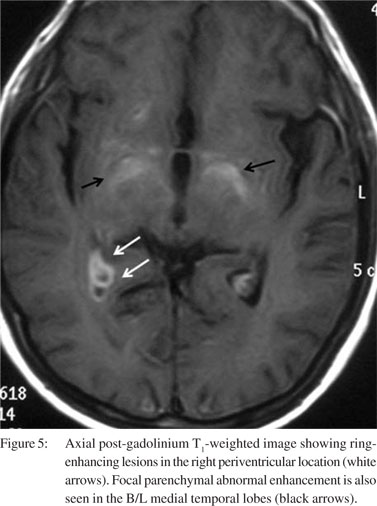

A 45-year-old man was suffering from cirrhosis of the liver due to chronic alcoholism (Child B; Child–Pugh score 7). He presented with fever and gait ataxia for the past 7 days. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination revealed: total cell count of 160 (70% lymphocytes)/µL (0–5 mononuclear cells); protein level of 167 mg/dL (15–50 mg/dL), sugar 14 mg/dL (40–70 mg/ dL); adenosine deaminase 6 IU/mL (<10 IU/mL). CSF cultures were sterile and tuberculosis-polymerase chain reaction (TB– PCR) was negative. CSF cryptococcal antigen (by latex agglutination method) was positive with a titre of 1:8. Serology for HIV was non-reactive and CD4 count was 535 cells/mm3. MRI of the brain revealed conglomerate ring-enhancing lesions in the peritrigonal area and right periventricular region, minimal perifocal oedema and ependymal enhancement (Figure 4) with focal parenchymal abnormal enhancement also seen in B/L medial temporal lobes (Figure 5). Serology for toxoplasmosis was negative. The patient was started on liposomal amphotericin and subsequently parenteral voriconazole was given. He showed improvement with this treatment and was discharged. He was doing well at 4 months of follow-up.

Case 2:

A 45-year-old man was suffering from cirrhosis of the liver due to chronic alcoholism (Child B; Child–Pugh score 7). He presented with fever and gait ataxia for the past 7 days. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination revealed: total cell count of 160 (70% lymphocytes)/µL (0–5 mononuclear cells); protein level of 167 mg/dL (15–50 mg/dL), sugar 14 mg/dL (40–70 mg/ dL); adenosine deaminase 6 IU/mL (<10 IU/mL). CSF cultures were sterile and tuberculosis-polymerase chain reaction (TB– PCR) was negative. CSF cryptococcal antigen (by latex agglutination method) was positive with a titre of 1:8. Serology for HIV was non-reactive and CD4 count was 535 cells/mm3. MRI of the brain revealed conglomerate ring-enhancing lesions in the peritrigonal area and right periventricular region, minimal perifocal oedema and ependymal enhancement (Figure 4) with focal parenchymal abnormal enhancement also seen in B/L medial temporal lobes (Figure 5). Serology for toxoplasmosis was negative. The patient was started on liposomal amphotericin and subsequently parenteral voriconazole was given. He showed improvement with this treatment and was discharged. He was doing well at 4 months of follow-up.

Discussion

Liver cirrhosis is an immunocompromised state. It predisposes to a variety of infections with 30% mortality.[1] One-third of admissions among patients with cirrhosis are due to bacterial infections.[2] The following defences are impaired in cirrhosis leading to increased susceptibility to infections: (i) Liver kupffer cells and sinusoidal endothelial cells (account 90% of reticuloendothelial system);[3] (ii) leukocyte activation, chemotaxis, phagocytosis, cytokine secretion, oxidative burst and microbicidal activity;[4] (iii) peripheral CD4 T-lymphocytes, complement levels, immunoglobulins.[5-7] Associated portosystemic shunting, hypersplenism, malnutrition, alcoholism, and immunosuppressive medication[5-7] further increase the susceptibility to infections. Additional risk factors predisposing to invasive fungal infections are exposure to broad-spectrum antimicrobials, cancer chemotherapy, indwelling vascular catheters, total parenteral nutrition, prior gastrointestinal surgery, renal failure, haemodialysis, transplantation and diabetes.[8-10] Candida, Aspergillus, Mucor, Cryptococcus neoformans are frequently encountered causing peritonitis, meningitis, pneumonia, cholangitis and blood stream and urinary tract infections.

The diagnosis of intracranial fungal infections in cirrhosis remains challenging and is often missed due to non-specific clinical signs, poor yield of the fungal cultures and limited information provided on radiodiagnosis. Clinicians ought to be aware of the possibility of fungal infections in cirrhosis as these may contribute to adverse outcomes.

References

- Tandon P, Garcia-Tsao G. Bacterial infections, sepsis, and multiorgan failure in cirrhosis. Semin Liver Dis. 2008;28:26–42.

- Fernández J, Navasa M, Gómez J, Colmenero J, Vila J, Arroyo V, et al. Bacterial infections in cirrhosis: epidemiological changes with invasive procedures and norûoxacin prophylaxis. Hepatology. 2002;35:140–8.

- Ghassemi S, Garcia-Tsao G. Prevention and treatment of infections in patients with cirrhosis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;21:77–93.

- Wasmuth HE, Kunz D, Yagmur E, Timmer-Stranghoner A, Vidacek D, Siewert E, et al. Patients with acute on chronic liver failure display “sepsis-like” immune paralysis. J Hepatol. 2005;42:195–201.

- Lombardo L, Capaldi A, Poccardi G, Vineis P. Peripheral blood CD3 and CD4 T-lymphocyte reduction correlates with severity of liver cirrhosis. Int J Clin Lab Res. 1995;25:153–6.

- Ono Y, Watanabe T, Matsumoto K, Ito T, Kunji O, Goldstein E. Opsonophagocytic dysfunction in patients with liver cirrhosis and low responses to tumor necrosis factor-alpha and lipopolysaccharide in patients’ blood. J Infect Chemother. 2004;10:200–7.

- Gomez F, Ruiz P, Schreiber AD. Impaired function of macrophage Fc gamma receptors and bacterial infection in alcoholic cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1122–8.

- Concia E, Azzini AM, Conti M. Epidemiology, incidence and risk factors for invasive candidiasis in high-risk patients. Drugs. 2009;69:5–14.

- Meersseman W, Lagrou K, Maertens J, Van Wijngaerden E. Invasive aspergillosis in the intensive care unit. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:205–16.

- Falcone M, Massetti AP, Russo A, Vullo V, Venditti M. Invasive aspergillosisis in patients with liver disease. Med Mycol. 2011;49:406–13.

|