Bhupendra Kumar Jain1, Pankaj Kumar Garg1, Anjay Kumar1, Kiran Mishra2, Debajyoti Mohanty1, Vivek Agrawal1

Department of Surgery1 and

Pathology2, University College of Medical Sciences and

Guru Teg Bahadur Hospital,

University of Delhi, India

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Bhupendra Kumar Jain

Email bhupendrakjain@gmail.com

Abstract

Background: Invasive colonic amoebiasis presents primarily with dysentery; colonic perforation occurs rarely. Cases of amoebic colonic perforations have been reported sporadically over the past 20 years.

Methods: A retrospective study was done in the surgical unit of a tertiary care hospital in North India. The case records of those patients were reviewed who underwent exploratory laparotomy from January 2011 to September 2012 and were diagnosed with amoebic colonic perforation on histopathological examination. Details concerning the clinical presentation, investigations, intraoperative findings, operative procedures, and postoperative outcomes were retrieved.

Results: Amongst, a total of 186 emergency exploratory laparotomies carried out during the study , 15 patients of amoebic colonic perforation were identified. The median age of the patients was 42 years (IQR 32.0–58.0) and the male to female ratio was 13:2. Previous history of colitis was present in only 1 patient. The preoperative diagnosis was perforation peritonitis in 12 patients; and intussusception, intestinal obstruction and ruptured liver abscess in 1 patient each. Ten patients had single perforation while 5 had multiple colonic perforations. All the patients except one had perforations in the right colon. Bowel resection was performed depending upon the site and extent of the colon involved—right hemicolectomy (8), limited ileocolic resection (6) and sigmoidectomy (1). Bowel continuity could be restored only in 2 of the 15 patients and a stoma was constructed in the remaining 13 patients. The overall mortality rate was found to be 40% (6/15).

Conclusion: Amoebic colonic perforation is associated with unusually high mortality.

|

48uep6bbphidvals|587 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Amoebiasis is a protozoal disease caused by Entamoeba histolytica. It is endemic in tropical countries and a health problem worldwide. The disease spectrum includes asymptomatic carrier, invasive intestinal amoebiasis and extraintestinal amoebiasis. Invasive amoebiasis presents clinically as dysentery, while fulminant colitis is rare. With the widespread use of anti-amoebic drugs, very few cases of amoebic colonic perforation were reported in the literature especially over the past 20 years. However, we observed an upsurge in the cases of amoebic colonic perforation over the past one-and-half years and it prompted us to analyse these cases retrospectively.

Methods

This retrospective study was done in a single surgical unit of a tertiary care teaching hospital of North India. The case records of all those patients were reviewed who underwent exploratory laparotomy from January 2011 to September 2012, and were diagnosed with amoebic colonic perforation on histopathological examination. Details concerning the clinical presentation, investigations, intraoperative findings, operative procedures and postoperative outcomes were retrieved.

Results

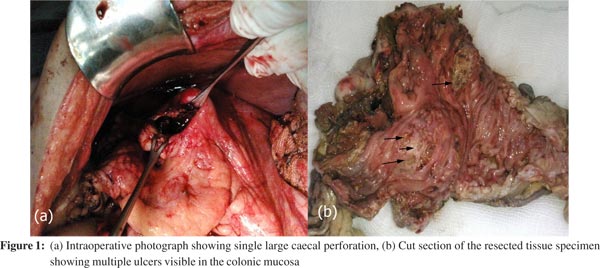

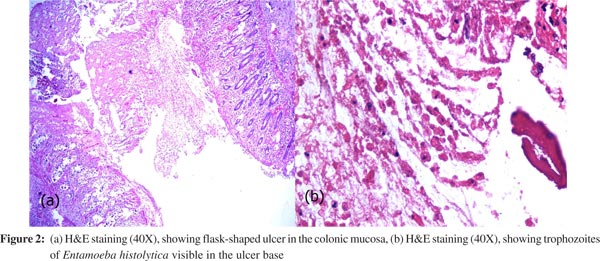

Amongst, a total of 186 emergency exploratory laparotomies carried out during the study ,15 patients of amoebic colonic perforation were identified. The disease was more common among men as compared to women (13:2). The median age of the patients was 42 years (IQR 32.0–58.0). The overall duration of symptoms ranged from 1 to 15 days with a median duration of 5 days. All the patients presented with generalized abdominal pain; 1 patient complained of blood-mixed stools for 2 days. None of the other patients complained of diarrhoea preceding or along with abdominal pain. One patient reported to have had fever. History of smoking and alcohol consumption was there in 60% and 66.7% patients, respectively. No patient was on any medication for any other disorder before the present illness. Physical examination revealed abdominal distension in all patients while signs of peritoneal irritation were present in 80% (12/15) patients. The preoperative diagnosis was perforation peritonitis in 12 patients; and intussusception, intestinal obstruction and ruptured liver abscess in 1 patient each. Among the cases of perforation peritonitis, 8 were considered to have ileal perforation; 2 to have appendicular perforation and 1 to have colonic perforation. Chest X-ray showed free gas under the diaphragm in 46.7% (7/15) of patients. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of the abdomen was undertaken in 1 patient suspected to have intussusception showing ruptured liver abscess, bilateral pleural effusion and gross intra-abdominal collection. Perforations were more common in the right colon (14/15) and 5 patients had multiple perforations (Figure 1). There were associated liver abscesses in 6 patients. Bowel resection was performed depending upon the site and extent of the colon involved—right hemicolectomy (8), limited ileocolic resection (6) and sigmoidectomy (1). Bowel continuity could be restored only in 2 of the 15 patients; stoma was constructed in other 13 patients. Postoperative complications were noted in 9 of the 15 patients: wound infection (9), severe sepsis and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) (6) and anastomotic dehiscence (2). Two patients who developed anastomotic leak following ileo-ascending anastomosis were re-explored; anastomosis was taken down and stoma was created. The overall mortality rate due to sepsis was 40% (6/15). Four of the 6 patients who died, had associated liver abscess. Amoebic serology was positive in all 10 patients in whom it was done. Histopathological examination revealed trophozoites of Entamoeba histolytica in the colonic wall, liver bscess wall, and even in the omentum in a few cases (Figure 2).

Discussion

Amoebiasis is highly prevalent throughout the world. The manifestations of the disease are protean and the clinical spectrum of amoebiasis may range from asymptomatic state to fulminating and fatal course. In the gastrointestinal system, the colon is the organ that bears the brunt of the disease. Amoebic infestation of the colon presents in five different forms—asymptomatic colonization, acute amoebic colitis, fulminant amoebic colitis (FAC), appendicitis and amoeboma. FAC progressing to intestinal perforation is the most feared complication and is associated with a high mortality despite treatment.[1] Complications requiring surgical intervention occur in 6%–11% of those with symptomatic disease.[2]

It is difficult to predict which patients with amoebiasis will develop complications and progress to FAC. The reasons for fulminant course in some patients while sparing a majority are unknown. However, some risk factors associated with FAC are male gender, age >60 years, tropical climate, excessive alcohol intake, parturition, associated liver abscess, persistent abdominal pain, poor nutrition, presence of peritonitis, hyponatraemia, hypokalaemia, and hypoalbuminaemia.[2,3]

Preoperative diagnosis of FAC is uncommon, despite the fact that amoebiasis is widely prevalent in our community. The main reason for this appears to be acute onset of symptoms which are indistinguishable from the surgical emergencies encountered more frequently. Eggleston et al.[4] suggested that various combinations of diarrhoea, bloody stools, enlarged tender liver or rectal ulceration in a patient of acute abdomen may suggest amoebiasis. Only one of our patients had these features indicating amoebiasis; however, he was clinically diagnosed to have intussusception showing a very low index of suspicion for amoebiasis. The presence of peritonitis mandates early laparotomy and further investigations/ or imaging are generally not warranted. If the presentation is less fulminant, an endoscopic examination is feasible and shows large geographic mucosal ulcers accompanied by yellow-green pseudomembranes. The mucosa adjacent to the ulcers appears either haemorrhagic or inflamed, resembling ischaemic colitis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).[2] This picture leads to an erroneous diagnosis of IBD and treatment with steroids is started which delays the diagnosis and further deteriorates the already critical condition of the patient.[5,6] In addition to endoscopy, plain abdominal X-rays may show megacolon, free air or a papery thin colon wall. Free gas under the diaphragm was seen in 46.7% of our patients despite evidence of colonic perforation on laparotomy. This may partly be explained by a slow leak through an extensively diseased bowel.[6] Aphthoid ulcers and marginal defects are characteristic of amoebic colitis on a barium enema.[2] In a nutshell, preoperative diagnosis is uncommon and ranges from 0% to 50% in various studies.[1,3,5] In our study, it was suspected in none of the patients probably because cases of amoebic colon perforation with their acute nature of presentation mimicked the more frequently encountered surgical emergencies such as ileal, duodenal, appendicular perforation or ruptured liver abscess. In our study, there is a striking association with the history of alcohol intake and the associated ruptured liver abscess.

This association was observed in 46.7% and 40% of our patients, respectively. Four of the 6 patients (66.7%) having associated liver abscess died. A study in the 1970s reported 26 patients of amoebic perforation of the bowel; 6 of 26 patients (26%) had associated amoebic liver abscess and all of them succumbed to the disease. In another study of 6 patients of amoebic bowel perforation, none of the patients had associated liver abscess; the reported mortality rate was 83.3% (5/6).[3] In a recent retrospective study of 122 patients of amoebic colonic perforation published in 2010,1 alcohol intake was found in 36% of patients. This study, however, did not comment on the presence of liver abscess, either diagnosed preoperatively or intraoperatively.[1] The preoperative diagnosis of liver abscess should alert the possibility of associated colonic perforation if there is persistent generalized abdominal pain in a patient with acute abdomen. The high mortality in patients of FAC and associated liver abscess may be related to a high disease burden. We also believe that the frequency of associated amoebic liver abscess may be much higher than the 40% that we have seen in our patients because small intraparenchymal liver abscesses may easily be missed on laparotomy.

Though amoebiasis may involve any part of the large bowel and occasionally distal ileum, amoebic colonic perforations has predilection for the right colon as is also evident in our study (14/15). Eggleston et al.[4] reported involvement of the right colon in all 26 patients of amoebic colonic perforation; there was isolated involvement of the right colon in 15 patients. An appropriate management of amoebic colon perforation has still not been finalized partly because the suspicion of amoebiasis as a cause of perforation peritonitis is low and the acute nature of fulminant colitis demands an immediate laparotomy whereby the definite diagnosis is reached only intraoperatively. Of late, there is greater emphasis on resection of the diseased colon with stoma formation and deferring the surgery for intestinal continuity.[1,2,5] In a study by Eggleston et al.[4] diversion and drainage was the commonly performed procedure and resection was reserved for gangrenous colon.

A similar line of management was echoed by Lubynski et al. in a study of 6 patients.[3] The major reason for avoidance of resection was perhaps the high mortality associated with this procedure, being 71% and 83% in the study by Eggleston et al.[4] and Lubynski et al.[3] respectively. On the contrary, in our study, the mortality rate was 40%. A similar mortality rate of 40% was seen in another study with a much higher mortality rate of 76.9% in those subjected to exteriorization without resection. We believe that resection of the diseased segment with stoma formation offers the best chances of survival as the septic focus is removed and further faecal contamination of the peritoneal cavity is obviated. Once the patient recovers from the disease, surgery for intestinal continuity can be performed after 3–6 months following the confirmation of the patency of the distal bowel segment. Either primary repair of perforation or resection with anastomosis is not favoured as this will result in unacceptably high rate of anastomotic dehiscence due to the inflamed and friable nature of the bowel.

Conclusion

Colon perforation is the most feared complication of amoebiasis resulting in high mortality rates despite all supportive treatment. The association of amoebic liver abscess is a curious feature that has been highlighted in our study. High mortality in patients having associated liver abscess may be a pointer to increased virulence of the organism. In essence, a high index of suspicion coupled with early and aggressive surgical resection of the involved colon and stoma formation will help in reducing the mortality in such patients.

References

Discussion

Amoebiasis is highly prevalent throughout the world. The manifestations of the disease are protean and the clinical spectrum of amoebiasis may range from asymptomatic state to fulminating and fatal course. In the gastrointestinal system, the colon is the organ that bears the brunt of the disease. Amoebic infestation of the colon presents in five different forms—asymptomatic colonization, acute amoebic colitis, fulminant amoebic colitis (FAC), appendicitis and amoeboma. FAC progressing to intestinal perforation is the most feared complication and is associated with a high mortality despite treatment.[1] Complications requiring surgical intervention occur in 6%–11% of those with symptomatic disease.[2]

It is difficult to predict which patients with amoebiasis will develop complications and progress to FAC. The reasons for fulminant course in some patients while sparing a majority are unknown. However, some risk factors associated with FAC are male gender, age >60 years, tropical climate, excessive alcohol intake, parturition, associated liver abscess, persistent abdominal pain, poor nutrition, presence of peritonitis, hyponatraemia, hypokalaemia, and hypoalbuminaemia.[2,3]

Preoperative diagnosis of FAC is uncommon, despite the fact that amoebiasis is widely prevalent in our community. The main reason for this appears to be acute onset of symptoms which are indistinguishable from the surgical emergencies encountered more frequently. Eggleston et al.[4] suggested that various combinations of diarrhoea, bloody stools, enlarged tender liver or rectal ulceration in a patient of acute abdomen may suggest amoebiasis. Only one of our patients had these features indicating amoebiasis; however, he was clinically diagnosed to have intussusception showing a very low index of suspicion for amoebiasis. The presence of peritonitis mandates early laparotomy and further investigations/ or imaging are generally not warranted. If the presentation is less fulminant, an endoscopic examination is feasible and shows large geographic mucosal ulcers accompanied by yellow-green pseudomembranes. The mucosa adjacent to the ulcers appears either haemorrhagic or inflamed, resembling ischaemic colitis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).[2] This picture leads to an erroneous diagnosis of IBD and treatment with steroids is started which delays the diagnosis and further deteriorates the already critical condition of the patient.[5,6] In addition to endoscopy, plain abdominal X-rays may show megacolon, free air or a papery thin colon wall. Free gas under the diaphragm was seen in 46.7% of our patients despite evidence of colonic perforation on laparotomy. This may partly be explained by a slow leak through an extensively diseased bowel.[6] Aphthoid ulcers and marginal defects are characteristic of amoebic colitis on a barium enema.[2] In a nutshell, preoperative diagnosis is uncommon and ranges from 0% to 50% in various studies.[1,3,5] In our study, it was suspected in none of the patients probably because cases of amoebic colon perforation with their acute nature of presentation mimicked the more frequently encountered surgical emergencies such as ileal, duodenal, appendicular perforation or ruptured liver abscess. In our study, there is a striking association with the history of alcohol intake and the associated ruptured liver abscess.

This association was observed in 46.7% and 40% of our patients, respectively. Four of the 6 patients (66.7%) having associated liver abscess died. A study in the 1970s reported 26 patients of amoebic perforation of the bowel; 6 of 26 patients (26%) had associated amoebic liver abscess and all of them succumbed to the disease. In another study of 6 patients of amoebic bowel perforation, none of the patients had associated liver abscess; the reported mortality rate was 83.3% (5/6).[3] In a recent retrospective study of 122 patients of amoebic colonic perforation published in 2010,1 alcohol intake was found in 36% of patients. This study, however, did not comment on the presence of liver abscess, either diagnosed preoperatively or intraoperatively.[1] The preoperative diagnosis of liver abscess should alert the possibility of associated colonic perforation if there is persistent generalized abdominal pain in a patient with acute abdomen. The high mortality in patients of FAC and associated liver abscess may be related to a high disease burden. We also believe that the frequency of associated amoebic liver abscess may be much higher than the 40% that we have seen in our patients because small intraparenchymal liver abscesses may easily be missed on laparotomy.

Though amoebiasis may involve any part of the large bowel and occasionally distal ileum, amoebic colonic perforations has predilection for the right colon as is also evident in our study (14/15). Eggleston et al.[4] reported involvement of the right colon in all 26 patients of amoebic colonic perforation; there was isolated involvement of the right colon in 15 patients. An appropriate management of amoebic colon perforation has still not been finalized partly because the suspicion of amoebiasis as a cause of perforation peritonitis is low and the acute nature of fulminant colitis demands an immediate laparotomy whereby the definite diagnosis is reached only intraoperatively. Of late, there is greater emphasis on resection of the diseased colon with stoma formation and deferring the surgery for intestinal continuity.[1,2,5] In a study by Eggleston et al.[4] diversion and drainage was the commonly performed procedure and resection was reserved for gangrenous colon.

A similar line of management was echoed by Lubynski et al. in a study of 6 patients.[3] The major reason for avoidance of resection was perhaps the high mortality associated with this procedure, being 71% and 83% in the study by Eggleston et al.[4] and Lubynski et al.[3] respectively. On the contrary, in our study, the mortality rate was 40%. A similar mortality rate of 40% was seen in another study with a much higher mortality rate of 76.9% in those subjected to exteriorization without resection. We believe that resection of the diseased segment with stoma formation offers the best chances of survival as the septic focus is removed and further faecal contamination of the peritoneal cavity is obviated. Once the patient recovers from the disease, surgery for intestinal continuity can be performed after 3–6 months following the confirmation of the patency of the distal bowel segment. Either primary repair of perforation or resection with anastomosis is not favoured as this will result in unacceptably high rate of anastomotic dehiscence due to the inflamed and friable nature of the bowel.

Conclusion

Colon perforation is the most feared complication of amoebiasis resulting in high mortality rates despite all supportive treatment. The association of amoebic liver abscess is a curious feature that has been highlighted in our study. High mortality in patients having associated liver abscess may be a pointer to increased virulence of the organism. In essence, a high index of suspicion coupled with early and aggressive surgical resection of the involved colon and stoma formation will help in reducing the mortality in such patients.

References

- Athié-Gutiérrez C, Rodea-Rosas H, Guízar-Bermúdez C, Alcántara A, Montalvo-Javé EE. Evolution of surgical treatment of amebiasis-associated colon perforation. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:82–7.

- Chen HT, Hsu YH, Chang YZ. Fulminant amebic colitis: recommended treatment to improve survival. Tzu Chi Med J. 2004;16:1–8.

- Lubynski RA, Isaacson C, Chappell J. Amoebic perforation of the bowel. S Afr Med J. 1981;59:176–7.

- Eggleston FC, Verghese M, Handa AK. Amoebic perforation of the bowel: experiences with 26 cases. Br J Surg. 1978;65:748–51.

- Ishida H, Inokuma S, Murata N, Hashimoto D, Satoh K, Ohta S. Fulminant amoebic colitis with perforation successfully treated by staged surgery: a case report. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:92–6.

- Gupta SS, Singh O, Shukla S, Raj MK. Acute fulminant necrotizing amoebic colitis: a rare and fatal complication of amoebiasis: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:6557.

|