Rajesh Rajalingam, Amit Javed, Anil K Agarwal

Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery,

GB Pant Hospital and Maulana Azad Medical College,

Delhi University, New Delhi - 110002, India

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Anil K Agarwal

Email: aka.hpb@gmail.com

48uep6bbphidvals|526 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Budd-Chiarisyndrome(BCS) results from an obstruction to the hepatic venous outflow and may occur at any level starting from the small hepatic veins(HV) to the cavo-atrial junction.[1]Various treatment modalities have been proposed for the management of this condition. In a significant proportion of these patients, surgical decompressive procedures (shunt operations)are effective in decongesting the liver and improving the survival before the onset of cirrhosis.[2]Mesoatrial shunt has been used for the management of patients with BCS due to combined hepatic venous and inferior vena cava (IVC) obstruction, not amenable to caval stenting. The procedure was first described in 1978 by Cameron et al in a patient of BCS with inferior vena cava obstruction to divert the portal blood flow into the right atrium.[3]As a significant proportion of patients have an underlying hypercoagulable state, variable shunt patency rates have been reported in literature. Blockage of such a shunt is a problem and results in recurrence of the disease. The management of such patients is difficult and the literature is limited. We report a case of Budd-Chiari syndrome who had undergone a meso-atrial shunt 4 years earlier and presented to us with a shunt block. The patient could be effectively managed with surgical revision of the shunt.

Case report

A 22-year-old male presented to our department with complaints of abdominal distention and breathlessness, requiring repeated pleurocentesis and abdominal paracentesis. The patient gave history of similar complaints 4 years back, when he was diagnosed with subacute BCS with combined HV and IVC obstruction. Initially he was managed with oral diuretics and repeated paracentesis. The IVC block was not amenable to percutaneous stenting, so he underwent surgical decompression in the form of a meso-atrial shunt via a right anterolateral thoracotomy and laparotomy. The patient had an uneventful post-operative recovery and the he was put on anticoagulants. The patient was followed up regularly (with Doppler ultrasound) up till 1 year after which he was lost to follow-up.On examination, the patient was thinly built and mildly jaundiced. He had a right anterolateral thoracotomy scar of the previous surgery. The abdominal examination revealed an upper midline scar with multiple abdominal wall collaterals (below upwards flow), a non-tender hepatomegaly (4 cm), splenomegaly (10 cm) and gross ascites. On investigating, his hematological and biochemical parameters were within normal limits except for deranged liver function tests. He had a total bilirubin of 5.2mg/dl with direct component of 1.4 mg/dl; SGOT: 38 IU/L; SGPT: 27 IU/L; and alkaline phosphatase of 273 IU/L with elevated INR: 2.5).Doppler ultrasound abdomen showed enlarged right and caudate lobes of the liver with monophasic wave form in the middle and left hepatic veins, with a flow reversal in the left hepatic vein. The right hepatic vein flow was attenuated and the IVC could not be delineated. Contrast enhanced CT of the thorax and abdomen showed gross right pleural effusion with right lung atelectasis and a blocked meso-atrial shunt.On further evaluation with magnetic resonance venography, occlusion of the hepatic veins with narrowing of intrahepatic IVC (for a length of 4 cm) was seen. The imaging also revealed altered liver echotexture suggestive of chronic liver disease with caudate lobe hypertrophy, ascites,gross right pleural effusion and a blocked mes-oatrialshunt.Transjugular liver biopsy showed mildly fibrotic portal area with focal central hemorrhagic necrosis. The IVC venogram showed a 50% blockage of IVC at the suprahepatic and intrahepatic regions. All the hepatic veins were blocked with a pressure gradient of 16 mmHg across the stenosis (Figure 1). A diagnosis of subacute Budd-Chiari syndrome with blocked meso-atrial shunt was made. He was further evaluated with an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy that showed 3 columns of grade II esophageal varices and chest skiagram that showed gross right pleural effusion .The workup for prothrombotic state including,factor V leiden mutation, sucrose lysis test,cardiolipin antibody and normal protein C activity level, protein S and anti-thrombin III levels, was negative and the antinuclear antibody titre was elevated (1:40).

Various surgical options for management were considered including revising the shunt.However we anticipated several problems.First would be the difficulty in approaching the area because of the previous surgery and resultant adhesions.A second challenge would be to locate another suitable site on the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) to place the graft.We also expected problems while going into the patient’s chest again. So a preoperative decision was taken to redo the abdominal part of the anastomosis by opening the graft by doing a thrombectomy, and if there was a good backflow from the cardiac end then only revising the anastomosis on the SMV and retaining the cardiac portion of the graft. Other porto-systemic shunts such as splenorenal shunt and side–side portocaval shunt were also considered.

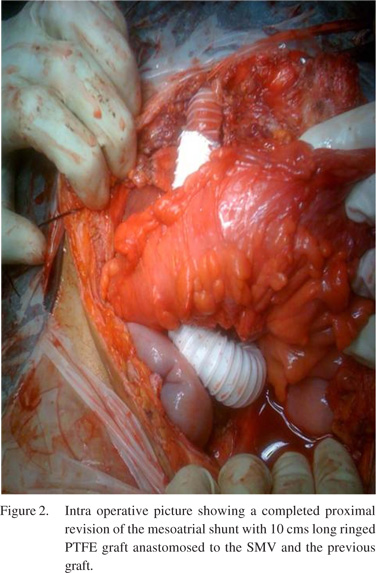

Intraoperative findings at laparotomy showed congestive hepatomegaly with moderate ascites and extensive collaterals in the greater omentum and falciform ligament. The inferior end of the prosthetic graft was found to be kinked and as we ascertained later, it was anastomosed to a collateral.On further dissection, we found superior mesenteric vein lying adjacent to this vessel which was of adequate diameter (10mm) with a good flow.In view of the combined block(of the hepatic veins and the IVC) with the availability of a good SMV and the anticipated technical difficulty of performing a repeat thoracotomy with revision of the cardiac part of the shunt, it was decided to proceed with a new PTFE graft anastomosis to the SMV at the lower end and thrombectomy of the upper end anastomosed to the atrium.We excised the distal end of the graft and after unclogging the proximal part, there was a good backflow of blood from the heart. We placed a 15 cm long 16mm ringed PTFE graft, which was anastomosed proximally to the excised end of the previous graft and distally to the side of SMV(Figure 2). Following the shunt revision, the portal pressure dropped from 29mmHg to 17mmHg. The surgical procedure was completed in four hours with 150 ml blood loss. Postoperatively, the patient developed transient liver failure which recovered with conservative management.Liver biopsy (both wedge and trucut biopsy from both lobes of liver) revealed predominantly well maintained lobular architecture with mild portal inflammation, prominent centrilobular congestion and focal perivenular fibrosis.The right pleural effusion and the ascites resolved.The patient received intravenous anticoagulation followed by oral anticoagulation and on the last Doppler (at 2 years follow-up) the shunt was found patent and the patient asymptomatic.

Discussion

Budd-Chiari syndrome is an uncommon cause of portal hypertension and it accounts for 7-9% of all portal hypertension cases in India.[4]In contrast to the West, the BCS in Eastern countries is predominantly chronic and the obstruction involves the IVC alone in upto 79.2% cases,both IVC and hepatic veins in upto 57.7% cases and the hepatic vein alone in only 0-32% cases.[5]A recent studyfrom India has shown a changing trend with HV thrombosis representing the majority of cases (59.1%).[6]Hypercoagulable states, tumors, pregnancy, oral contraceptive pills and infections are proposed as predominant underlying etiologies.

Various methods, both medical and surgical, have been tried for the management of BCS. The mainstay of the treatment is surgical management includes various shunt procedures employed in patients before the onset of cirrhosis, and liver transplantation for patients with established cirrhosis and end stage liver disease. Selection of these procedures depends on the level of obstruction. For patients with obstruction at HV alone, portocaval (side-to-side),meso-caval and splenorenal shunts are preferred. However, in patients with IVC obstruction and/or an infrahepatic to right atrium pressure gradient of 20mmHg, meso-caval and portocaval shunts may not effectively decompress the liver.[2]Therefore for combined blocks, mesoatrial or cavoatrial with side-to-side portocaval shuntsare preferred.Recently IVC stenting followed by side-to-side portocaval shunts have been described, which is also our preferred line of management in these cases. According to Klein et al if there is >75% narrowing of the IVC lumen or if the IVC gradient exceeds 25 cm of water, a mesoatrial shunt should be preferred.[7] Mesoatrial shunt, a technically easier operation, does not jeopardise the patient’s chances of having a liver transplant, should it be required in the future, as it does not interfere with the anatomy at the portahepatis. However, the use of mesoatrial shunt for patients with IVC occlusion has not been accepted uniformly as a few reports show a poor patency rate. This has been attributed to the shunt compression at the level of the xiphisternum, long graft in a low flow venous system and unrelieved infrahepatic IVC.Using the ringed PTFE grafts, however,the patency rates have significantly improved.

Behera et al showed 100% patency rate of 10 mesoatrial shunts over a follow-up period of 40 months.[4] Similarly 75-100% patency rate have been reported in other series.[7-9] The largest series by Wang et al,including 70 patients, showed a 61.1% 5 year patency rate for mesoatrial shunt.[10] The various options for treating shunt thrombosis depend on the duration of thrombosis. In acutely thrombosed shunts, percutaneous angioplasty helps in restoring the shunt patency. In progressive chronic obstruction, shunt revision or a new porto systemic shunt has been advocated. In a study from John Hopkins, Klein et al showed revision of mesoatrial shunt as an effective surgical option in a case of chronic mesoatrial shunt thrombosis (2 out of 10 patients) with silicone sleeve reinforced prosthesis, with patent shunt on 3 year follow-up.[7]

Though we planned a shunt revision in this patient, the intraoperative findings led us to opt for intraabdominal revision of the proximal part of the shunt with thrombectomy. The technical points to be kept in mind while constructing a mesoatrial shunt are to expose the superior mesenteric vein at its widest part and to avoid division of collaterals and tributaries, so as to ensure a good inflow into the shunt.[4]There should be no tension on the graft and it should have a smooth layout through the transverse mesocolon without any kinks. One should be very careful and meticulous to make sure that the anastomosis is done to the SMV only, as some of the large collaterals in the region can masquerade as the SMV and make shift shunts do not have good long term patency. The patient was maintained on long term anticoagulation following the shunt revision.We could successfully demonstrate the feasibility of the procedure with a shunt patency at 2 year follow-up.

References

- Janssen HL, Garcia-Pagan JC, Elias E, Mentha G, Hadengue A, Valla DC; European Group for the Study of Vascular Disorders of the Liver.Budd-Chiari syndrome: a review by an expert panel. J Hepatol. 2003;38:364–71.

- Orloff MJ, Daily PO, Orloff SL, Girard B, Orloff MS. A 27- year experience with surgical treatment of Budd–Chiari syndrome. Ann Surg. 2000;232:340–52

- Cameron JL, Maddrey WC. Mesoatrial shunt: a new treatment for the Budd–Chiari syndrome. Ann Surg. 1978;187:402–06.

- Behera A, Menakuru SR, Thingnam S, Kaman L, Bhasin DK, Kochher R, et al. Treatment of Budd-Chiari syndrome with inferior vena caval occlusion by mesoatrial shunt. Eur J Surg. 2002;168:355–9.

- Valla DC. Hepatic venous outflow tract obstruction etiopathogenesis: Asia versus the West. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:S204–11.

- Amarapurkar DN, Punamiya SJ, Patel ND. Changing spectrum of Budd-Chiari syndrome in India with special reference to nonsurgical treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:278–85.

- Klein AS, Sitzmann JV, Coleman J, Herlong FH, Cameron JL. Current management of the Budd-Chiari syndrome. Ann Surg. 1990;212:144–9.

- Khanduri P, Murlidharan, Nathaniel P, Jesudason SB, Lal NP, Krishnaswamy S, et al. Maso-atrial shunt in the surgical treatment of Budd–Chiari syndrome. Aust N Z J Surg.1983;53:309–15.

- Wang ZG, Zhu Y, Wang SH, Pu LP, Du YH, Zhang H, et al. Recognition and management of Budd–Chiari syndrome: report of one hundred cases. J Vasc Surg. 1989;10:149–59.

- Wang ZG, Zhang FJ, Yi MQ, Qiang LX. Evolution of management for Budd-Chiari syndrome: a team’s view from 2564 patients. ANZ J Surg. 2005;75:55–63.

|