48uep6bbphidvals|498

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

An accurate diagnosis to locate the cause of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding in children can be very challenging; often the final diagnosis is made only at laparotomy. Amongst the unusual causes for GI hemorrhage in children are various vascular lesions which are described as angiodysplasia. This report describes the case of a young boy who manifested GI hemorrhage as malena, but could not be accurately diagnosed as angiodysplasia until the laparotomy and was successfully managed by a conservative surgical treatment.

Case report

A ten-year-old boy presented with history of malena for last 8 years. The episodes of malena were intermittent and self limiting, varying in frequency and amount of bleeding. There was no history of abdominal pain, lump, vomiting, hematemesis or altered bowel habits. There was no history of anorexia, weight loss, jaundice or bleeding from other sites. The patient had a past history of multiple hospitalizations across different hospitals for anemia and multiple blood transfusions. He was referred to us from another hospital for further management.

Physical examination was unremarkable except for pallor. Laboratory investigations revealed a normal platelet count and prothrombin time. Digital subtraction angiography revealed normal superior and inferior arterial systems. MRI of abdomen and pelvis was normal. Colonoscopy was unremarkable. 99mTc labelled RBC scintigraphy could not identify the source of bleeding. Capsule endoscopy revealed prominent vessels distal to the ligament of Treitz in the jejunum and proximal ileum. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed a suspicious polypoidal lesion in the proximal jejunum with prominent vessels on it.

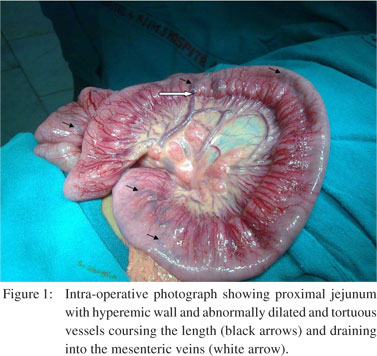

Since the patient continued to be symptomatic and a definite diagnosis could not be reached, an exploratory laparotomy was performed. The small intestine and colon were normal on palpation; no intraluminal polyp could be palpated. The entire jejunum and proximal ileum were hyperemic with abnormally dilated and tortuous vessels coursing the length (Figure 1). These vessels were seen to drain into several dilated veins in the mesentery. The colon, mesocolic vessels and rest of the viscera were normal. All the abnormally dilated vessels draining into the mesenteric veins were individually ligated in continuity just at the mesenteric border. Following ligation, the hyperaemia of the bowel wall reduced and the vessels coursing the length of the bowel shrank in calibre within minutes.

The post-operative course was uneventful. During succeeding 6 months follow up the patient has been asymptomatic with no further episodes of malena.

Discussion

Common causes of malena/lower gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding in children include Meckel’s diverticulum, sloughed polyp, Henoch- Schonlein purpura, inflammatory bowel disease, vascular malformations such as angiodysplasia and arteriovenous malformations.

Approximately 10-15% of mucosal or variceal hemorrhages from the upper GI tract may present with malena alone, without hematemesis.[1] Gastrointestinal bleeding of unknown cause in children remains a diagnostic challenge for both physicians and surgeons. Application of newer diagnostic techniques is helpful and safe for identifying the cause of GI bleeding in children.

There are a wide range of endoscopic and radiological investigations, such as colonoscopy, upper GI endoscopy, capsule endoscopy, selective visceral angiography, digital subtraction angiography, MRI angiography, 99mTc labelled RBC scintigraphy and Meckel’s scan which can help in the diagnosis. The final diagnosis can usually be established during laparoscopy or laparotomy with intra-operative enteroscopy or angiography.

In this case the exact etiology remained uncertain even after extensive investigations. Most of the common causes of malena in children were ruled out by pre-operative investigations and intra-operative examination. The most likely diagnosis in our case would be a vascular malformation such as angiodysplasia or vascular ectasia. Angiodysplasia of the colon as a cause of lower GI bleeding is diagnosed frequently in the elderly, with defined clinical characteristics. In the pediatric population there is little experience; only six cases have been reported.[2] The majority (77%) of angiodysplasia are located in the cecum and/or ascending colon, 15% are located in the jejunum and/or ileum and the remainder are distributed throughout the alimentary tract.[3]

Angiodysplasia is considered as a very rare cause of GI bleed in children and hence a delay in diagnosis has been reported.2 This also holds true in our patient who remained undiagnosed for eight years since the onset of symptoms. This delay may lead to a fatal outcome in children, if the bleeding increases in severity, as has been reported in occasional cases.[4]

The most important investigation for diagnosis of angiodysplasia is angiography or arteriography, which locates and delineates the lesion. In our patient capsule endoscopy revealed prominent vessels in the jejunum and proximal ileum, which was confirmed on laparotomy. These findings suggest angiodysplasia of the jejunum as the cause of malena in our patient.

The optimal management in such cases with abnormal mesenteric vasculature or vascular ectasia is uncertain and depends on the severity and rate of bleeding. A conservative medical approach is indicated for many patients, while surgical resection constitutes definitive treatment in case of massive hemorrhage or recurrent bleeding. Bipolar electrocoagulation and vasopressin infusion or gel foam embolization have been tried to control bleeding.[5] However, the latter measures usually lead to late recurrences of bleeding.

In our case a novel surgical treatment was performed based on ligation of the abnormally dilated mesenteric veins in continuity.

Since the hyperemia and abnormal vessels extended from the proximal jejunum up till the proximal ileum, intestinal resection would have significantly reduced small intestinal length. By ligating the abnormally dilated mesenteric vessels in continuity, surgical resection was avoided and intestinal length was preserved. There are only two cases in the literature where a similar procedure was performed for angiodysplasia of the colon and small bowel with good results.[6,7] In our case the patient is doing well six months after the surgery with no further episodes of malena. The good outcome in our case warrants further evaluation of this novel technique in management of similar cases.

References

Discussion

Common causes of malena/lower gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding in children include Meckel’s diverticulum, sloughed polyp, Henoch- Schonlein purpura, inflammatory bowel disease, vascular malformations such as angiodysplasia and arteriovenous malformations.

Approximately 10-15% of mucosal or variceal hemorrhages from the upper GI tract may present with malena alone, without hematemesis.[1] Gastrointestinal bleeding of unknown cause in children remains a diagnostic challenge for both physicians and surgeons. Application of newer diagnostic techniques is helpful and safe for identifying the cause of GI bleeding in children.

There are a wide range of endoscopic and radiological investigations, such as colonoscopy, upper GI endoscopy, capsule endoscopy, selective visceral angiography, digital subtraction angiography, MRI angiography, 99mTc labelled RBC scintigraphy and Meckel’s scan which can help in the diagnosis. The final diagnosis can usually be established during laparoscopy or laparotomy with intra-operative enteroscopy or angiography.

In this case the exact etiology remained uncertain even after extensive investigations. Most of the common causes of malena in children were ruled out by pre-operative investigations and intra-operative examination. The most likely diagnosis in our case would be a vascular malformation such as angiodysplasia or vascular ectasia. Angiodysplasia of the colon as a cause of lower GI bleeding is diagnosed frequently in the elderly, with defined clinical characteristics. In the pediatric population there is little experience; only six cases have been reported.[2] The majority (77%) of angiodysplasia are located in the cecum and/or ascending colon, 15% are located in the jejunum and/or ileum and the remainder are distributed throughout the alimentary tract.[3]

Angiodysplasia is considered as a very rare cause of GI bleed in children and hence a delay in diagnosis has been reported.2 This also holds true in our patient who remained undiagnosed for eight years since the onset of symptoms. This delay may lead to a fatal outcome in children, if the bleeding increases in severity, as has been reported in occasional cases.[4]

The most important investigation for diagnosis of angiodysplasia is angiography or arteriography, which locates and delineates the lesion. In our patient capsule endoscopy revealed prominent vessels in the jejunum and proximal ileum, which was confirmed on laparotomy. These findings suggest angiodysplasia of the jejunum as the cause of malena in our patient.

The optimal management in such cases with abnormal mesenteric vasculature or vascular ectasia is uncertain and depends on the severity and rate of bleeding. A conservative medical approach is indicated for many patients, while surgical resection constitutes definitive treatment in case of massive hemorrhage or recurrent bleeding. Bipolar electrocoagulation and vasopressin infusion or gel foam embolization have been tried to control bleeding.[5] However, the latter measures usually lead to late recurrences of bleeding.

In our case a novel surgical treatment was performed based on ligation of the abnormally dilated mesenteric veins in continuity.

Since the hyperemia and abnormal vessels extended from the proximal jejunum up till the proximal ileum, intestinal resection would have significantly reduced small intestinal length. By ligating the abnormally dilated mesenteric vessels in continuity, surgical resection was avoided and intestinal length was preserved. There are only two cases in the literature where a similar procedure was performed for angiodysplasia of the colon and small bowel with good results.[6,7] In our case the patient is doing well six months after the surgery with no further episodes of malena. The good outcome in our case warrants further evaluation of this novel technique in management of similar cases.

References

- Boyle JT. Gastrointestinal bleeding in infants and children. Pediatr Rev. 2008;29:39–52.

- de la Torre Mondragon L, Vargas Gomez MA, Mora Tiscarreno MA, Ramirez Mayans J. Angiodysplasia of the colon in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1995;30:72–5.

- Al-Mehaidib A, Alnassar S, Alshamrani AS. Gastrointestinalangiodysplasia in three Saudi children. Ann Saudi Med. 2009;29:223–6.

- Valoria VJM, Digiuni AEM, Perez Tejerizo G. Bleeding intestinal angiodysplasia. Report of a pediatric case. An Esp Pediatr. 1987;26:124–8.

- De Diego JA, Molina LM, Diez M, Delgado I, Moreno A, Solana M, et al. Intestinal angiodysplasia: retrospective study of 18 cases. Hepatogastroenterology. 1988;35:255–9.

- Assenza M, Ricci G, Clementi I, Antoniozzi A, Simonelli L, Modini C. Gastrointestinal bleeding in emergency setting: two cases of intestinal angiodysplasia and unusual conservative surgical treatment. Clin Ter. 2006;157:345–8.

- Biandrate F, Piccolini M, Francia L, Rosa C, Battaglia A, Pandolfi U. Bleeding small bowel angiodysplasia: unusual form of conservative treatment. Chir Ital. 2003;55:475–9.