SK Mathur, Amrita Duhan, Sunita Singh, Monika Aggarwal, Garima Aggarwal, Rajeev Sen, Sneh Singh, Shilpa Garg

Department of Pathology,

Pt. BD Sharma Post Graduate

Institute of Medical Sciences,

Rohtak, India

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Amrita Duhan

Email: amrita.duhan@gmail.com

Abstract

Background and aim: Gallstones are known to produce diverse histopathological changes in the gall bladder. Our aim was to correlate various gallstone characteristics (number, size, weight, volume and morphological type) with the type of mucosal response in gall bladder (inflammation, hyperplasia, metaplasia and carcinoma).

Methods: The study was conducted on 330 open cholecystectomy specimens with complete gallstones. The stones were assessed for various parameters i.e. number, size, weight, volume and morphological type. For microscopy, sections were obtained from the fundus, body and neck of the gallbladder. Additional sections were taken from abnormal looking areas.

Results: Out of the 330 cases, 194 (59%) had mixed stones, 84 (25%) combined, 30 (9%) pigment and 22 (7%) had cholesterol stones. Number of stones varied from a single calculus in 131 (39.6%) cases, double in 29 (8.8%) and multiple in the remaining 170 (51.6%) cases. Cholecystitis, hyperplasia, metaplasia and carcinoma were more commonly seen with mixed and multiple stones. The average weight of calculi in cholecystitis was 2.551 gm, in hyperplasia 3.619 gm, metaplasia 4.549 gm and 17.96 gm in cases with carcinoma. Similarly, average volume of the stone(s) was 2.664 ml in cholecystitis, 3.742 ml in hyperplasia, 4.532 ml in metaplasia and 19.178 ml in carcinoma. The average calculus size (2.147 cm) was found to be maximum in cases with carcinoma, followed by hyperplasia (1.187 cm), metaplasia (1.145 cm) and cholecystitis (1.136 cm).

Conclusion: As the weight, volume and size of the stone increases the changes in the gall bladder mucosa changes from cholecystitis, hyperplasia, metaplasia, dysplasia, to carcinoma.

|

48uep6bbphidvals|491 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Gall bladder, gallstone, cholecystitis, hyperplasia, metaplasia, carcinoma Cholelithiasis has been described as a disease of civilization.[1] They have been observed in Egyptian mummies dating as far

back as 3400 B.C. It appears likely that Charaka (two centuries B.C.) and Sushruta (six centuries B.C.) from India were also familiar with this disease of the biliary tract.[2]

Gallstones are a major cause of morbidity and mortality throughout the world. The prevalence varies with age, sex and ethnic group. Most people are unaware of the disease and remain asymptomatic for life.[3] Frequently, chronic cholecystitis presents a large range of associated lesions such as cholesterolosis, muscle hypertrophy, parietal fibrosis, polypoid and adenomatous proliferation of mucous glands, metaplasia, hyperplasia and dysplasia.[4] A significantly higher incidence of carcinoma gall bladder has been observed in patient population with a traditionally high incidence of gallstones or in persons harboring gallstones for longer duration.[5]

Gallstones are categorized as asymptomatic, associated with biliary colic and associated with complications of cholelithiasis.[6] Once stones are symptomatic or present with complications, there is little debate that therapeutic intervention is necessary. The question of what to do about asymptomatic gallstones has prevailed since the turn of previous century. This study correlated various gallstone characteristics (number, size, weight, volume and morphological type) with the type of mucosal response in gall bladder (inflammation, hyperplasia, metaplasia and carcinoma).

Methods

The present study was conducted on 330 open cholecystectomy specimens with complete gallstones after due approval of project by the Post Graduate board of studies that includes ethical considerations. The stones were assessed for various parameters i.e. number, size, weight, volume and morphological type. The tissue was properly sampled and processed by routine histological technique for paraffin embedding and sectioning at 4 micron thickness. Four sections including the entire wall were obtained; two from the body and one each from the fundus and neck of the gall bladder. Additional sections were taken from abnormal appearing mucosa. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin stain.

Physical characteristics of stones were assessed as per the following parameters: 1) type: based on morphology;3 2) number: single / double / multiple; 3) size: average of two major diameters with a vernier caliper (accuracy: 0.01 cm). In the event of multiple gallstones, the diameter of largest and smallest stone was recorded; 4) weight: using electronic analytical and precision balance(accuracy: 0.001 gm); 5) volume: by water displacement (accuracy: 0.1 ml).

The pattern of response in the gall bladder mucosa such as type of inflammation, cholesterolosis, mucocele, hyperplasia, metaplasia, dysplasia and malignant changes was studied with regard to number, size, weight, volume and morphological type of the stone(s). The various morphological responses were then categorized under four broad categories – cholecystitis, hyperplasia, metaplasia and carcinoma.

Statistical analysis was performed by using analysis of variance (ANOVA) for averages and chi-square test for contingency tables and proportions.

Results

Of the total 330 specimen examined in our study 287 (86.97%) were from female and 43 (13.03%) were from male patients. Male to female ratio was 1:6.6. Eighty (24.24%) patients belonged to the age group of 40-49 years. Gall bladder size was normal in 194 (59%), enlarged in 95 (29%) and fibrotic in 41 (12%) specimens. The average gall bladder wall was found to be normal (<3 mm) in 153 (46.4%) cases while it was thickened >3 mm) in the remaining 177 (53.6%) cases.

Out of the 330 cases, 194 (59%) had mixed stones, 84 (25%) combined, 30 (9%) pigment and 22 (7%) had cholesterol stones. Number of stones varied from a single calculus in 131 (39.6%) cases, double in 29 (8.8%) and multiple in the remaining 170 (51.6%) cases.

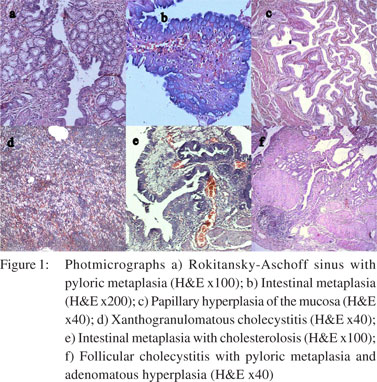

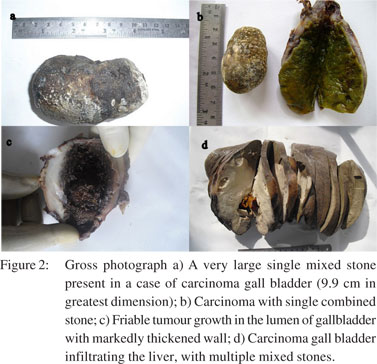

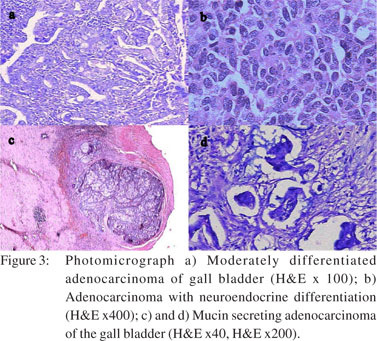

All cases were subjected to microscopy and were categorized as per their microscopy pattern. In specimen with more than one mucosal response, the predominant pattern was taken into consideration for categorization (one condition per case) (Table 1). The majority of cases had cholecystitis of which 149 (45%) were chronic cholecystitis followed by 41 (12%) acute-on-chronic cholecystitis cases.Cholesterolosis was noted in 19 (6%) cases, while there were only 2 cases (1%) of mucocele. Cholecystitis with hyperplasia (both adenomatous and adenomyomatous changes) was observed in 24 cases (8%) and cholecystitis with metaplasia in 59 cases (18%) (Figure 1). Eight cases (2%) of carcinoma were observed, 7 of them adenocarcinomas (3 mucin secreting, 3 non-mucin secreting and 1 with neuroendocrine differentiation) and the remaining one was a poorly differentiated carcinoma (Figures 2 and 3). All the patients suffering from carcinoma were females. The youngest was 42 years old while the oldest was 70 years of age. Out of the 8 cases, clinical suspicion was documented in only 4 cases. The remaining 4 were incidental findings, whose diagnosis was made on microscopic examination.

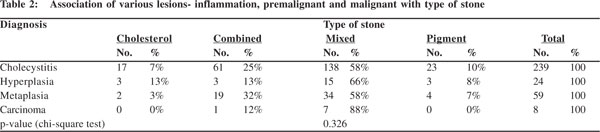

Type of stone

Cholecystitis, hyperplasia, metaplasia and carcinoma i.e. all mucosal changes were more commonly seen with mixed stones. In carcinoma, 88% (7 out of 8 cases) had mixed stones. In cases with metaplasia, besides the 34 (58%) cases with mixed stones, 19 (32%) had combined stones. While 15 (66%) of the 24 cases of hyperplasia had mixed stones, in rest 9 cases cholesterol, combined and pigment stones appeared in equal numbers (3 each) (Table 2). The association of mucosal response with type of stone was not found to be statistically significant (p= 0.326).

Type of stone

Cholecystitis, hyperplasia, metaplasia and carcinoma i.e. all mucosal changes were more commonly seen with mixed stones. In carcinoma, 88% (7 out of 8 cases) had mixed stones. In cases with metaplasia, besides the 34 (58%) cases with mixed stones, 19 (32%) had combined stones. While 15 (66%) of the 24 cases of hyperplasia had mixed stones, in rest 9 cases cholesterol, combined and pigment stones appeared in equal numbers (3 each) (Table 2). The association of mucosal response with type of stone was not found to be statistically significant (p= 0.326).

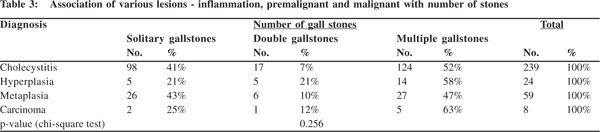

Number of stones

All the benign, premalignant and malignant lesions were associated more with multiple gallstones. Another interesting finding was that cholecystitis, hyperplasia, metaplasia and carcinoma i.e. all the lesions were more common with solitary gallstones when compared with gall bladders with two stones (Table 3). But statistically the association between the numbers and type of mucosal response was not found to be significant (p = 0.256).

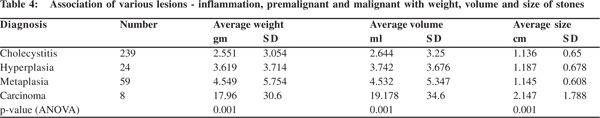

Average weight, volume and size

The average weight of calculi in cholecystitis was 2.551 gm, in hyperplasia 3.619 gm, metaplasia 4.549 gm and 17.96 gm in cases with carcinoma. Similarly, average volume of the stone(s) was 2.664 ml in cholecystitis, 3.742 ml in hyperplasia, 4.532 ml in metaplasia and 19.178 ml in carcinoma. Likewise, the average size of stone(s) (2.147 cm) was also found to be maximum in cases with carcinoma, followed by hyperplasia (1.187 cm), metaplasia (1.145 cm) and cholecystitis (1.136 cm) (Table 4). This correlation between average weight, volume and size of the stone with type of mucosal response was found to be statistically significant (p <0.05, ANOVA).

Discussion

The estimated prevalence of gallstone disease in India has been reported between 2-29%. In India, this disease is seven times more common in north (stone belt) than in south India.[3] The present study undertook the evaluation of 330 cholecystectomy specimens with cholelithiasis with an aim to correlate various gallstone characteristics with host mucosal response.

The age of the patients ranged from 16 to 82 years. Majority of the patients (24.24%, 80 cases) were in the age group of 40- 49 years with a mean age of 45.2 years. No age group was completely free of gallstones. The main sufferers were females; the male to female ratio being 1:6.6, an incidence similar to that reported by others.[3,7-10] The age and sex distribution of present as well as previous studies indicates that the incidence of cholelithiasis is higher in older age group and in females. Female sex hormones and sedentary habits of most women in India expose them to factors that possibly promote formation of gallstones.[3]

Mixed stones are the most commonly encountered stones in north India.[3,8] In contrast to our study where combined stones were the next common type, cholesterol stones were the second most common variety in studies by Mohan et al[3] and Tyagi et al[8]. There are no specific explanations for this variation. We could not document any specific difference in age of the patients with different types of stone,a finding supported by Jayanthi et al.[11]

Multiple stones have been found more commonly (60.4%) than solitary stones (39.6%) in our study as well as previous reports.[7,12-15] This indicates that cases with multiple number of stones are more symptomatic than those with solitary stones. Precancerous changes of the gall bladder mucosa are of particular importance from both clinical and pathological standpoints. Improved diagnostic procedures aid in detection of early and/or resectable invasive carcinoma more frequently. Precancerous conditions however, seem to be not infrequently overlooked by pathologists.[16]

We observed cholecystitis with hyperplasia in 8% cases. Cases of both adenomatous and adenomyomatous hyperplasia were included, although cases with simple epithelial hyperplasia including pseudostratification of epithelium were not considered. This led to an apparent decrease in the incidence of hyperplasia in our study when compared with Khanna et al[7] in which incidence of hyperplasia was found to be 59%. Elfvinget al[17] proposed the hypothesis that primary cholelithiasis causes secondary hyperplasia because of mechanical irritation caused by the calculi.

Metaplasia is not an infrequent finding in gall bladder. Chronic cholecystitis with metaplasia was noted in 18% of our cases. Likewise, intestinal metaplasia was noted in 8% and pyloric metaplasia in 10% cases. Our results are comparable to those reported by other studies with almost similar distribution of metaplasia cases.[4,7]

Of the 330 cases, we found carcinomatous change in 8 (2%) of them. All the patients affected were females with a higher mean age of 61 years. This was consistent with other studies in which patients with cancer had a higher mean age as compared to other gall bladder diseases.[5,18-20]

When association of the four main types of mucosal response (cholecystitis, hyperplasia, metaplasia and carcinoma) was compared with the calculus type using chi-square test, no statistically significant association was found (p=0.326). Our results are in conformity with the findings of Khanna et al.[7] During our investigations we categorized our cases on the basis of number of stones we encountered as single, double or multiple. We observed that benign, premalignant and malignant lesions were more frequently associated with multiple gallstones. Amongst all lesions metaplastic changes were relatively more frequent with solitary gallstones. These associations however were relative and no statistical association could be demonstrated between mucosal response and number of gallstones (p=0.256).

Vitetta et al[21] and Hsing et al[22] observed that gall bladder cancer patients were more likely to have multiple stones. Juvonen et al[15] stated that histological evidence of biliary complications are more often in patients with multiple stones than in those with solitary stones. Domeyer et al[12] concluded that the solitary gallstones were the most important predictors for severe inflammation. Khanna et al[7] and Roa et al[13] could not document any association between the two in their respective studies.

In the present study we noted that the average size of gallstones in cases with carcinoma was significantly greater (2.1cm) as compared to that in cases of inflammation and premalignant lesions. A strong correlation has been reported between the size of the gallstones and the incidence of gall bladder carcinoma. In a study of more than 1600 patients with gall bladder disease, Lowenfells et al20] reported that 40% of the patients with gall bladder carcinoma had stones that were >3 cm in size. Vitetta et al,[21] Hsing et al[22] and Diehl et al[23] have also reported similar findings. But case control studies by Roa et al[13] and Moerman et al[14] found no relationship between stone size and gall bladder cancer.

In our study, the average volume and weight of the stone was found to progressively increase from cases of cholecystitis, hyperplasia, metaplasia to a maximum in cases of carcinoma.The association between average size, weight and volume of calculi with the mucosal response was found to be statistically significant (p<0.05). Not many studies have investigated the association of mucosal response with weight and volume of gallstones. Roa et al[13] in their case control study reported that average gallstone weight, volume and density was greater in cases with carcinoma than in controls. In this study, logistic regression analysis showed that every 1 gm increase in stone weight, increased the likelihood of gall bladder cancer by approximately 5%, and volumes over 10 ml had an odds ratio 11 times higher than controls for developing cancer. The results were statistically significant (p<0.05). Hsing et al[22] also documented that stones in cancer patients were heavier (p=0.006) than those of other gallstone patients. Radiologically the gallstone volume can be assessed using the ellipsoid formula.[24]

While a cause and effect relationship cannot be substantiated with the present study, constant erosion of the gall bladder wall by gallstones over time may constitute a risk. The identification of premalignant modifications in the morphologic background of chronic cholecystitis is an argument in favor of the metaplasia-dysplasia-neoplasia sequence.[4]

In conclusion it was seen that the average weight, volume and size of the gall bladder significantly correlated in increasing order with cholecystitis, hyperplasia, metaplasia and carcinoma.

References

Discussion

The estimated prevalence of gallstone disease in India has been reported between 2-29%. In India, this disease is seven times more common in north (stone belt) than in south India.[3] The present study undertook the evaluation of 330 cholecystectomy specimens with cholelithiasis with an aim to correlate various gallstone characteristics with host mucosal response.

The age of the patients ranged from 16 to 82 years. Majority of the patients (24.24%, 80 cases) were in the age group of 40- 49 years with a mean age of 45.2 years. No age group was completely free of gallstones. The main sufferers were females; the male to female ratio being 1:6.6, an incidence similar to that reported by others.[3,7-10] The age and sex distribution of present as well as previous studies indicates that the incidence of cholelithiasis is higher in older age group and in females. Female sex hormones and sedentary habits of most women in India expose them to factors that possibly promote formation of gallstones.[3]

Mixed stones are the most commonly encountered stones in north India.[3,8] In contrast to our study where combined stones were the next common type, cholesterol stones were the second most common variety in studies by Mohan et al[3] and Tyagi et al[8]. There are no specific explanations for this variation. We could not document any specific difference in age of the patients with different types of stone,a finding supported by Jayanthi et al.[11]

Multiple stones have been found more commonly (60.4%) than solitary stones (39.6%) in our study as well as previous reports.[7,12-15] This indicates that cases with multiple number of stones are more symptomatic than those with solitary stones. Precancerous changes of the gall bladder mucosa are of particular importance from both clinical and pathological standpoints. Improved diagnostic procedures aid in detection of early and/or resectable invasive carcinoma more frequently. Precancerous conditions however, seem to be not infrequently overlooked by pathologists.[16]

We observed cholecystitis with hyperplasia in 8% cases. Cases of both adenomatous and adenomyomatous hyperplasia were included, although cases with simple epithelial hyperplasia including pseudostratification of epithelium were not considered. This led to an apparent decrease in the incidence of hyperplasia in our study when compared with Khanna et al[7] in which incidence of hyperplasia was found to be 59%. Elfvinget al[17] proposed the hypothesis that primary cholelithiasis causes secondary hyperplasia because of mechanical irritation caused by the calculi.

Metaplasia is not an infrequent finding in gall bladder. Chronic cholecystitis with metaplasia was noted in 18% of our cases. Likewise, intestinal metaplasia was noted in 8% and pyloric metaplasia in 10% cases. Our results are comparable to those reported by other studies with almost similar distribution of metaplasia cases.[4,7]

Of the 330 cases, we found carcinomatous change in 8 (2%) of them. All the patients affected were females with a higher mean age of 61 years. This was consistent with other studies in which patients with cancer had a higher mean age as compared to other gall bladder diseases.[5,18-20]

When association of the four main types of mucosal response (cholecystitis, hyperplasia, metaplasia and carcinoma) was compared with the calculus type using chi-square test, no statistically significant association was found (p=0.326). Our results are in conformity with the findings of Khanna et al.[7] During our investigations we categorized our cases on the basis of number of stones we encountered as single, double or multiple. We observed that benign, premalignant and malignant lesions were more frequently associated with multiple gallstones. Amongst all lesions metaplastic changes were relatively more frequent with solitary gallstones. These associations however were relative and no statistical association could be demonstrated between mucosal response and number of gallstones (p=0.256).

Vitetta et al[21] and Hsing et al[22] observed that gall bladder cancer patients were more likely to have multiple stones. Juvonen et al[15] stated that histological evidence of biliary complications are more often in patients with multiple stones than in those with solitary stones. Domeyer et al[12] concluded that the solitary gallstones were the most important predictors for severe inflammation. Khanna et al[7] and Roa et al[13] could not document any association between the two in their respective studies.

In the present study we noted that the average size of gallstones in cases with carcinoma was significantly greater (2.1cm) as compared to that in cases of inflammation and premalignant lesions. A strong correlation has been reported between the size of the gallstones and the incidence of gall bladder carcinoma. In a study of more than 1600 patients with gall bladder disease, Lowenfells et al20] reported that 40% of the patients with gall bladder carcinoma had stones that were >3 cm in size. Vitetta et al,[21] Hsing et al[22] and Diehl et al[23] have also reported similar findings. But case control studies by Roa et al[13] and Moerman et al[14] found no relationship between stone size and gall bladder cancer.

In our study, the average volume and weight of the stone was found to progressively increase from cases of cholecystitis, hyperplasia, metaplasia to a maximum in cases of carcinoma.The association between average size, weight and volume of calculi with the mucosal response was found to be statistically significant (p<0.05). Not many studies have investigated the association of mucosal response with weight and volume of gallstones. Roa et al[13] in their case control study reported that average gallstone weight, volume and density was greater in cases with carcinoma than in controls. In this study, logistic regression analysis showed that every 1 gm increase in stone weight, increased the likelihood of gall bladder cancer by approximately 5%, and volumes over 10 ml had an odds ratio 11 times higher than controls for developing cancer. The results were statistically significant (p<0.05). Hsing et al[22] also documented that stones in cancer patients were heavier (p=0.006) than those of other gallstone patients. Radiologically the gallstone volume can be assessed using the ellipsoid formula.[24]

While a cause and effect relationship cannot be substantiated with the present study, constant erosion of the gall bladder wall by gallstones over time may constitute a risk. The identification of premalignant modifications in the morphologic background of chronic cholecystitis is an argument in favor of the metaplasia-dysplasia-neoplasia sequence.[4]

In conclusion it was seen that the average weight, volume and size of the gall bladder significantly correlated in increasing order with cholecystitis, hyperplasia, metaplasia and carcinoma.

References

- Kozoll DD, Dwyer G, Meyer KA. Pathologic correlation ofgall stones, a review of 1,874 autopsies of patients with gallstones.Arch Surg. 1959;79:514–36.

- Prakash A. Chronic cholecystitis and cholelithiasis in India. Int Surg. 1968;49:79–85.

- Mohan H, Punia RPS, Dhawan SB, Ahal S, Sekhon MS. Morphological spectrum of gallstone disease in 1100 cholecystectomies in north India. Indian J Surg. 2005;67:140–2.

- Stancu M, Caruntu ID, Giusca S, Dobrescu G. Hyperplasia, metaplasia, dysplasia and neoplasia lesions in chronic cholecystitis – a morphologic study. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2007;48:335–42.

- Wasim B, Kafil N, Hadi NI, Afshan G. Age and gender related frequency of cancer in chronic cholelithiasis. J Surg Pak. 2010;15:48–51.

- Bowen JC, Brenner HI, Ferrante WA, Maule WF. Gallstone disease. Pathophysiology, epidemiology, natural history and treatment options. Med Clin North Am. 1992;76:1143–57.

- Khanna R, Chansuria R, Kumar M, Shukla HS. Histological changes in gall bladder due to stone disease. Indian J Surg. 2006;68:201–4.

- Tyagi SP, Tyagi N, Maheshwari V, Ashraf SM, Sahoo P. Morphological changes in diseased gall bladder : a study of 415 cholecystectomies at Aligarh. J Indian Med Assoc. 1992;90:178–81.

- Singh UR, Agarwal S, Misra K. Histopathological study of xanthogranulomatouscholecystitis. Indian J Med Res. 1989;90:285–8.

- Badke A, Schwenk W, Bohm B, Stock W. Histopathological changes of gall bladder and liver parenchyma in symptomatic cholelithiasis. Dtsch Med Wochenschr.1993;118:809–13.

- Jayanthi V, Palanivelu C, Prasanthi R, Mathew S, Srinivasan V. Composition of gallstones in Coimbatore district of Tamil Nadu state. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1998;17:134–5.

- Domeyer PJ, Sergentanis TN, Zagouri F, Tzilalis B, Mouzakioti E, Parasi A, et al. Chronic holecystitis in elderly patients. Correlation of the severity of inflammation with the number and size of the stones. In Vivo. 2008;22:269–72.

- Roa I, Ibacache G, Roa J, Araya J, Anetxabala XD, Munoz S. Gallstones and gall bladder cancer –volume and weight of gallstones are associated with gall bladder cancer: a case control study. J Surg Oncol. 2006;93:624–8.

- Moerman CJ, Lagerwaard FJ, Bueno de Mesquita HB, van Dalen A, van Leeuwen MS, Schrover PA. Gallstone size and the risk of gallbladder cancer. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1993;28:482–6.

- Juvonen T, Niemela O, Makela J, Kairaluoma MI. Characteristics of symptomatic gall bladder disease in patients with either solitary or multiple cholesterol gallstones. Hepatogastroenterology. 1994;41:263–6.

- Mukuda T, AndohN, Matsushiro T. Precancerous lesions of the gallbladder mucosa. Tohoku J Exp Med. 1985;145:387–94.

- Elfving G, Teir H, Degert H, Makela V. Mucosal hyperplasia in the gallbladder demonstrated by plastic models. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1969;77:384–8.

- Cariati A, Cetta F. Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses of the gallbladder are associated with black pigment gallstone formation: a scanning electron microscopy study. Ultrastruct Pathol. 2003;27:265–70.

- Gurleyik G, Gurleyik E, Ozturk A, Uralmiser S. Gallbladder carcinoma associated with gallstones. Acta Chir Belg. 2002;102:203–6.

- Lowenfels AB, Walker AM, Althaus DP, Townsend G, Domell of L. Gallstone growth, size, and risk of gallbladder cancer: an interracial study. Int J Epidemiol. 1989;18:50–4.

- Vitetta L, Sali A, Little P, Mrazek L. Gallstones and gallbladder carcinoma. Aust N Z J Surg. 2000;70:667–73.

- Hsing AW, Gao YT, Han TQ, Rashid A, Sakoda LC, Wang BS, et al. Gallstones and the risk of biliary tract cancer: a population based study in China. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:1577–82.

- Diehl AK. Gallstone size and the risk of gallbladder cancer. JAMA. 1983;250:2323–6.

- Donald JJ, Fache JS, Buckley AR, Burhenne HJ. Gallbladder contractility: variation in normal subjects. Am J Roentgenol. 1991;157:753–6.

|