48uep6bbphidvals|438

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Hydatid disease is a zoonotic infection caused by larval forms

of Echinococcus granulosus and is endemic in the

Mediterranean area, Middle East, South America, India,

northern China and Australia. Cystic hydatid disease usually

affects the liver (50–70%) and less frequently the lung, spleen,

kidney, bone, and brain.[1] Hepatic echinococcal cysts generally

remain asymptomatic until their expanding size or their spaceoccupying effect result in symptoms. Most common

presentation is abdominal pain or a palpable mass in the right

upper quadrant. Rupture of or episodic leakage from a hydatid

cyst may produce fever, pruritis, urticaria, eosinophilia, or

anaphylaxis. Infection of the cyst can facilitate the development

of liver abscesses and mechanical local complications such as

mass effect on bile ducts and vessels that can induce

cholestasis, portal hypertension and Budd-Chiari

syndrome.[2, 3] In addition, the presence of daughter cysts in an

older cyst represents a significant risk of recurrence after

surgery. Therefore, treatment of liver hydatid cysts is

considered mandatory in symptomatic cysts and is

recommended in viable cysts because of the risk of severe

complications.[1]

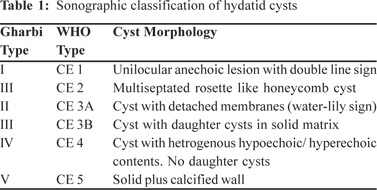

Treatment of hepatic hydatid is based on ultrasound staging

and considerations of the size, location and manifestations of

cysts, and the overall health of the patient. There are several

classification schemes for liver hydatid cysts based on their

ultrasound appearance; the initial classification by Gharbi et al

and the WHO Informal Working Group on Echinococcosis

(IWGE) classification are the most commonly preferred.[4] Hassen Gharbi classified hepatic hydatid into five types based

on sonographic appearance.[5] WHO classification is almost the

same as Gharbi’s, with Gharbi type II corresponding to CE 3A

of the WHO classification, and vice versa. However, there are

two important additions in the WHO classification: the

predominantly solid cyst with daughter cysts, which was not

explicitly included in Gharbi’s classification, has found a place

in the CE 3 slot, and the types are now grouped according to

their biological activity (Table 1). This has important

consequences for treatment decisions.[6]

For many years surgery was the only available treatment

for hepatic hydatid cysts and was associated with high

morbidity, mortality, and relapse rates of 32%, 8%, and 20%,

respectively.[6] The failure rate for medical management of

hydatid cysts with benzimidazole compounds (i.e., albendazole

and mebendazole) used alone approaches 25%, with most cases

of relapse occurring within 2 years of cessation of therapy.[7] In

recent years percutaneous, minimally, invasive treatment of

hepatic hydatid cysts has developed into an attractive

alternative to surgery and benzimidazole derivatives for certain

cyst stages.[6] It has been tried with considerable success in

types I and II, with encouraging long term results.[8] However

reports on percutaneous treatment of type III cysts are limited.

At our institution surgery is still the mainstay of treatment of

Gharbi type III. We are presenting our experience with treating

these patients using minimally invasive techniques in a select

group of patients who refused surgery.

Methods

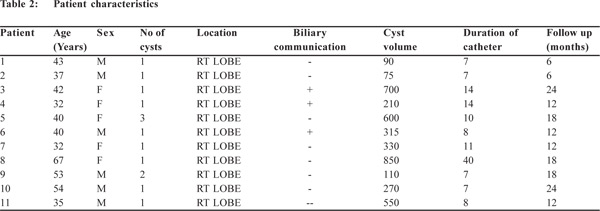

From March 1994 to November 2007, 11 patients with 13 Gharbi

type III (WHO type CE 2 and CE 3B) hepatic hydatid cysts

were enrolled for our study. This study was conducted in

Department of Radiodiagnosis, Sanjay Gandhi Post-graduate

Institute of Medical Sciences, Lucknow (UP), India. There

were 6 female and 5 male patients; age ranging from 32 – 67 yrs

(mean age 43 yrs). The chief presenting complaints were right upper quadrant (RUQ) pain (n = 9), RUQ mass (n = 7), and

epigastric discomfort (n = 8). In 2 patients the cysts were

incidentally detected during imaging for unrelated complaints.

No patient had prior surgical intervention. The diagnosis of

heterogeneous hepatic hydatid cysts was based on

characteristic cyst morphology on cross sectional imaging,

ultrasonography (USG) (Figure 1) and computerized

tomography (CT) (Figure 2) and indirect hemagglutination

(IHA) test. All heterogeneous hepatic hydatid cysts were

located in the right lobe. The average cyst diameter was 9.6

cms (range 5 -13 cms). All type I and II hydatid cysts referred

to our department during this period, were treated with

puncture, aspiration, injection and re-aspiration (PAIR)

technique and were not included in this study. At each follow

up a through clinical examination and abdominal ultrasonography was performed. All ultrasonographic

examinations were evaluated by two authors (SSB and SM).

The diameter and echo pattern of the cysts were documented.

In addition, the liver, biliary tree, and other abdominal organs

were carefully examined for evidence of residual or recurrent

cysts.

Technique

Written informed consent was obtained and detailed technique,

other available modes of treatment, and complication rates

were explained to all the patients. The patients were subjected

to USG examination before the procedure. All patients received

oral albendazole 10mg /kg body weight, starting four week

pre-procedure and continuing for 4 weeks after the procedure.

After overnight fast an IV line was secured and 100 mg of hydrocortisone and 50 mg of diphenhydramine were given 20

minutes before the procedure. The procedure was performed

in the intervention suite under combined fluoroscopy and

ultrasound guidance, under local anesthesia and moderate

sedation. An anesthesiologist was always available to manage

potential anaphylaxis.

The cyst was punctured under sonographic guidance with

an 18 G needle. Longest available tract between the liver capsule

and the cyst wall was chosen as the site of puncture. The cyst

aspirate where obtained (n=7) was sent for microbiological

analysis for the presence of scolex and its mobility. A 0.035

super stiff guide wire (Cook, Bloomington Inc, USA) was

inserted into the cyst and the tract was sequentially dilated to

18 - 24 French. A large bore sheath (Amplatz Renal introducer

set, Cook Bloomington Inc, USA) was subsequently inserted

and stabilized manually. A suction catheter of 14 Fr size was

passed through it and the cyst contents were actively sucked

mechanically, using a suction apparatus. The catheter was

directed in different quadrants of cysts for effective removal.

Complete evacuation of solid portions (pearly white grapelike

membranes) (Figure 3) was attempted at the initial stage in all

patients. After satisfactory removal, the suction catheter was

withdrawn, retaining the large bore catheter. A cystogram was

then performed to look for any residual solid elements and to

demonstrate any biliary ductal communication. If more solid

elements were seen (Figure 4a), the suction procedure was

repeated until the clearance of cavity (Figure 4b). After

achieving cyst unilocularity, the large bore sheath was

exchanged with a 16 Fr to 20 Fr large bore catheter, which was

connected to a bag for drainage. The 48 hour drain output from

these catheters was sent for estimation of bile salts to reconfirm

lack of any possibility of biliary ductal communication.

Absolute alcohol, used as a scolicidal agent, was then instilled

in the cyst cavity, which was re-aspirated after 20 minutes.

Volume of absolute alcohol to be injected was taken as 50% of

the drain output in last 24 hours. The patients were discharged

48 hours later, after downsizing the catheter to 12-14 Fr. In one

patient who had 3 hydatid cysts, a two stage procedure was

performed, where two cysts were addressed in first, and the

third in the second session. No scolicidal/ sclerosing agent

was instilled in three patients who demonstrated biliary ductal

communication on repeat cystogram.

Follow up serial ultrasound and drainage pattern of cysts

were evaluated on outpatient visits every 7-10 days. When the

cyst aspirate decreased to <10 ml per 24 hours the catheter was

removed. In cases, where the cyst drainage fluid was bile stained

or the catheter output was persistently higher, the catheter

was retained for longer periods till spontaneous decrease in

output was encountered. In one patient there was persistent

output, even after 32 days, in whom endoscopic retrograde

cholangiography (ERCP) was performed and a plastic stent

was placed.

After catheter removal, follow-up sonogram was performed

at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months and every year thereafter. Decrease in

cyst size, progressive solidification, formation of a

pseudotumour or complete disappearance were regarded as

positive signs of response.

Results

The results are summarized in Table 2. The cysts were

completely evacuated in all patients. All patients tolerated the

procedure well, with no anaphylaxis. On microscopy, cyst

aspirate (obtained in n=7 patients) showed presence of

laminated membranes and protoscolices confirming that these

cysts were active. Cystogram immediately after the procedure

did not show any biliary ductal communication. However in 3

patients bilio-cystic communication was noted 48 hours later.

Spontaneous reduction in drain output was noted in 10 patients.

In 1 patient when the output did not reduce after 32 days,

ERCP with papillotomy and stenting was performed.

Subsequently this patient also showed diminished drain output.

Mean duration of catheter placement was 11.3 days (range 7 to

40 days). In uncomplicated patients (n = 8) the average duration

of hospital stay was 3 days (range 1 to 4 days). In patients with

bilio-cystic communication (n = 3) mean hospital stay was 4

days (range 3 to 6 days). Minor complications were encountered

in 7 patients in the form of urticaria (n = 3), reactive pleural

effusions (n = 3), pain (n = 6), and fever (n = 2). All patients

responded to symptomatic treatment. Follow up serial

ultrasound was performed on all patients. After percutaneous

treatment, the cysts gradually underwent a sequence of

sonographic changes from appearance of high-level internal

echoes (a heterogeneous pattern), obliteration by echogenic

material (a pseudotumor pattern), decreased echogenicity, and

finally a normal pattern of echoes. The cyst was considered to

have disappeared if it was no longer visualized on

ultrasonography and the area was replaced by an ill-defined

echogenic area or a normal echo pattern. Complete healing

was seen in 9 patients and formation of so called pseudotumour

in 4 patients. The mean follow up was 15.23 months (6 months

– 2 years).

Discussion

Percutaneous treatment of hepatic hydatidosis, initially

introduced in the mid-1980s, has developed into an attractive

alternative to surgery and benzimidazole derivatives for certain

cyst stages.[3,9] This treatment modality for hepatic hydatidosis

destroys the germinal layer with scolicidal agents or evacuates

the entire endocyst.[6] It has been tried with considerable

success, especially for the unilocular hepatic hydatid cysts,

with encouraging long term results.8,10,11,12,13,14 The first successful

percutaneous drainage of hepatic hydatid cyst was reported

by Mueller el al in 1985.[9] They drained the cyst percutaneously

under imaging guidance and then lavaged the cavity through

a catheter using silver nitrate and hypertonic saline solutions.

All liver function tests remained normal on one year follow up.

Subsequently in 1990, a new therapeutic approach involved

the following steps: puncture the cyst, aspirate cyst fluid, inject

a scolicidal agent, and re-aspirate the cyst content (PAIR).[10,11] Giorgio et al and Kabaalioglu et al reported repeated failures of

PAIR in multivesiculated cysts or cysts with predominantly

solid contents and daughter cysts, Gharbi type III (CE2 and

CE3B), possibly attributable to difficulty in extracting solid

components and cyst membranes.[15,16] Giorgio et al showed that

PAIR of multivesiculated cysts does not allow complete healing

and in 30% of cases resulted in an intracystic recurrence that

required up to four repeat procedures.[15,16] These findings

prompted most clinicians to use PAIR exclusively for unilocular

cysts, with or without detached endocysts. For this reason

Gharbi type III cysts are now preferably treated with other percutaneous techniques based on the aspiration of the “solid”

content of the cyst, the germinal and the laminated layer,

through a large-bore catheter or device.[6] Two types of

approaches are currently in use: the catheterization technique[17] and the modified catheterization techniques, in particular

PEVAC (percutaneous evacuation), MoCaT (modified

catheterization technique), and DMFT (dilatable multi-function

trocar).[6] Haddad et al used large-bore 14 Fr van Sonnenberg

sump catheters for drainage and suction of membranes in type

IV cysts.[18] We used larger 24 Fr bore catheter to achieve the

same. This along with wide distal end holes and val large side

holes offered better extraction of the solid cyst contents. We

found this to offer significant advantage for sufficient

evacuation of solid elements.

A large-bore cutting-aspiration device was used by Saremi

and McNamara in 32 patients to fragment and evacuate

daughter cysts and the laminated membrane.[19] A 2-year followup

showed a high rate of success (90%) and a low incidence of

major complications (3%). Vuitton et al treated 699

multivesiculated abdominal cysts with a device called DMFT

which was linked to an aspiration apparatus to extract the

endocyst, daughter cysts and other cystic contents.[20] Thereafter, the cavity was irrigated with 10–20% saline and if

necessary curettage was performed. The catheter remained in

the cavity for 2–3 days. No deaths but four anaphylactic

reactions were observed in their series. The recurrence rate in

a 3-year follow-up was 2.3% in-situ and 1% in other locations. Schipper et al treated 12 patients with unilocular and

multivesiculated cysts, including complicated ones with

PEVAC.[21] Aspiration and evacuation of cyst content were

performed with a 14 Fr catheter. Cysto-biliary fistulas were

treated with an endoprosthesis introduced endoscopically into

the common bile duct. In a mean period of 17.9 months (range

4 – 30 months) seven cysts disappeared and five decreased in

size. The main complications of this procedure were caused by

cysto-biliary fistulas and secondary infections. These

complications prolonged hospitalization from 11.5 (range 8–14

days) to 72.3 days (range 28–128 days).

Giorgio et al in their study proved efficacy of double

percutaneous aspiration and ethanol injection for previously

untreated patients with viable univesicular and multivesicular

hydatid liver cysts not only in the short term, but also over

long term and showed that this technique has a lower cost,

shorter hospital stay and fewer recurrences.1 We also used

absolute alcohol as scolicidal agent in hepatic hydatid cysts

which did not have any biliary ductal communication.

As compared to the available literature, results of our study

were better with mean duration of catheter placement being

11.3 days (range 7 to 40 days). Number of days of hospitalization

was only 3 days in uncomplicated patients (n = 8). In patients

with bilio-cystic communication (n = 3) mean hospital stay was

4 days (range 3 to 6 days). Complete healing was seen in 9

patients and formation of so called pseudotumour in 4 patients, which was chosen as end point of our study, thus showing a

100% success rate with a mean follow up of 15.23 months and

no recurrence.

The major risks of percutaneous techniques are

anaphylactic shock, secondary echinococcosis caused by

spillage of cystic fluid and chemical cholangitis caused by

contact of the scolicidal agent with the biliary tree. It is imperative to have resuscitation measures in place, to choose

a safe approach to the cyst, to give peri-interventional

prophylaxis with benzimidazoles and to exclude

communications with the biliary tree before injection of any

scolicidal agent.[6]

To avoid potential spillage we chose the longest available

tract between the liver capsule and the cyst wall as the site of

puncture. Thus the liver parenchyma can have a sealing effect

against the inadvertent spillage during the procedure

(tamponade effect). We ensured that all safety measures were

in place by giving 100 mg of hydrocortisone and 50 mg of

diphenhydramine 20 minutes before the procedure. The

procedure was performed under local anaesthesia but an

anesthesiologist was always available during the procedure to

manage potential anaphylaxis. No serious complications,

anaphylaxis or deaths were encountered in our series. Minor complications such as urticaria, fever and reactive pleural

effusion were encountered in 7 patients who responded to

symptomatic treatment. However three patients showed a minor

complication of biliary fistula which was managed by retaining

catheter for longer periods of time in 2 patients until the

spontaneous output reduced to <10cc/ day and by endoscopic

retrograde cholangiography (ERCP) with plastic stent

placement in 1 patient.

Prophylactic albendazole therapy was used in our study

with two considerations. First, in animal studies it has been

reported that albendazole therapy offers protective effect

against pro-spillage.[22] Khuroo et al in a prospective randomized

controlled study have shown that prophylactic albendazole

therapy prior to percutaneous treatment has better results as

compared with percutaneous treatment or albendazole therapy

alone.[23]

Thus we conclude that percutaneous treatment is a safe

and effective alternative therapy in treating Gharbi type III

hepatic hydatid cysts for patients who refuse surgery and

require a shorter hospital stay.

References

- Giorgio A, Di Sarno A, de Stefano G, Liorre G, Farella N,

Scognamiglio U, et al. Sonography and clinical outcome of viable

hydatid liver cysts treated with double percutaneous aspiration and ethanol injection as first-line therapy: efficacy and long-term follow-up. Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:W186–92.

- Ammann RW, Eckert J. Cestodes. Echinococcus. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1996;25:655–89.

- Khuroo MS, Wani NA, Javid G, Khan BA, Yattoo GN, Shah AH, et al. Percutaneous drainage compared with surgery for hepatic hydatid cysts. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:881–7.

- Turgut AT, Akhan O, Bhatt S, Dogra VS. Sonographic spectrum of hydatid disease. Ultrasound Q. 2008;24:17–29.

- Gharbi HA, Hassine W, Brauner MW, Dupuch K. Ultrasound examination of the hydatic liver. Radiology. 1981;139:459–63.

- Junghanss T, da Silva AM, Horton J, Chiodini PL, Brunetti E.

Clinical management of cystic echinococcosis: state of the art, problems, and perspectives. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79:301–11.

- Lucey BC, Kuligowska E. Radiologic management of cysts in the abdomen and pelvis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:562–73.

- Polat KY, Balik AA, Oren D. Percutaneous drainage of hydatid cyst of the liver: long-term results. HPB (Oxford). 2002;4:163–6.

- Mueller PR, Dawson SL, Ferruci JT Jr, Nardi GL. Hepatic echinococcal cyst: successful percutaneous drainage. Radiology. 1985;155:627–8.

- Filice C, Pirola F, Brunetti E, Dughetti S, Strosselli M, Foglieni

CS. A new therapeutic approach for hydatid liver cysts. Aspiration and alcohol injection under sonographic guidance. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:1366–8.

- Gargouri M, Ben Amor N, Ben Chehida F, Hammou A, Gharbi

HA, Ben Cheikh M, et al. Percutaneous treatment of hydatid cysts (Echinococcus granulosus). Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1990;13:169–73.

- Salama H, Farid Abdel-Wahab M, Strickland GT. Diagnosis and treatment of hepatic hydatid cysts with the aid of echo-guided percutaneous cyst puncture. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:1372–6.

- Ustunsoz B, Akhan O, Kamiloglu MA, Somuncu I, Ugurel MS, Cetiner S. Percutaneous treatment of hydatid cysts of the liver: long-term results. Am J Roentgenol. 1999;172:91–6.

- Men S, Hekimoglu B, Yucesoy C, Arda IS, Baran I. Percutaneous treatment of hepatic hydatid cysts: an alternative to surgery. Am J Roentgenol. 1999;172:83–9.

- Giorgio A, Tarantino L, de Stefano G, Francica G, Mariniello N,

Farella N, et al. Hydatid liver cyst: an 11-year experience of treatment with percutaneous aspiration and ethanol injection. J Ultrasound Med. 2001;20:729–38.

- Kabaalioglu A, Ceken K, Alimoglu E, Apaydin A. Percutaneous imaging-guided treatment of hydatid liver cysts: do long-term results make it a first choice? Eur J Radiol. 2006;59:65–73.

- Akhan O, Dincer A, Gokoz A, Sayek I, Havlioglu S, Abbasoglu

O, et al. Percutaneous treatment of abdominal hydatid cysts with hypertonic saline and alcohol. An experimental study in sheep. Invest Radiol. 1993;28:121–7.

- Haddad MC, Sammak BM, Al-Karawi M. Percutaneous treatment of heterogenous predominantly solid echopattern echinococcal cysts of the liver. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2000;23:121–5.

- Saremi F, McNamara TO. Hydatid cysts of the liver: long-term

results of percutaneous treatment using a cutting instrument.

AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;165:1163–7.

- Vuitton DA, Zhi Wang X, Li Feng S, Sheng Chen J, Shou Li Y, Li

SF, et al. PAIR-derived US-guided techniques for the treatment

of cystic echinococcosis: a Chinese experience (e-letter).

Gut. 2002.

- Schipper HG, Lameris JS, van Delden OM, Rauws EA, Kager

PA. Percutaneous evacuation (PEVAC) of multivesicular

echinococcal cysts with or without cystobiliary fistulas which

contain non-drainable material: first results of a modified PAIR

method. Gut. 2002;50:718–23.

- Morris DL, Chinnery JB, Hardcastle JD. Can albendazole reduce the risk of implantation of spilled protoscoleces? An animal study. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1986;80:481–4.

- Khuroo MS, Dar MY, Yattoo GN, Zargar SA, Javaid G, Khan

BA, et al. Percutaneous drainage versus albendazole therapy in hepatic hydatidosis: a prospective, randomized study. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:1452–9.