48uep6bbphidvals|429

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Introduction

Infarction of the greater omentum is a rare cause of acute

abdomen with only few cases reported in the literature. Given its low incidence and lack of awareness among clinicians, an

accurate preoperative diagnosis is unusual and patients may be explored for peritonitis due to other causes. Omental

gangrene presenting as a late complication following corrosive ingestion has not been reported in the literature. To our

knowledge we report here the first case of omental gangrene occurring nearly three months after corrosive ingestion,

presenting as an acute abdomen and requiring surgery.

Case Report

A 40-year old female had ingested corrosive acid 3 months

ago, following which she developed abdominal pain associated with vomiting and was managed conservatively. She had no

respiratory distress, hemoptysis or hematemesis. She developed dysphagia to solids and semisolids 1 month later.

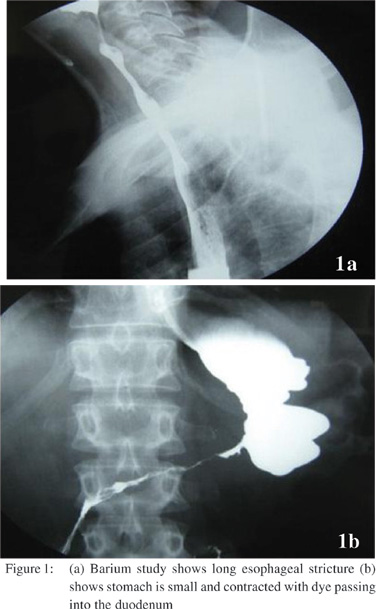

Barium study showed a long esophageal stricture (Figure 1a) with a small capacity contracted stomach, and passage of dyeinto the duodenum (Figure 1b). She was planned for an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and possible dilatation of

esophageal stricture. Esophagoscopy revealed a stricture just

below the upper esophageal sphincter for which dilatation was

attempted. A day after dilatation, patient came with acute onset

severe pain abdomen.On examination her pulse rate was 120/

min and BP 100/60 mmHg. Abdominal examination showed signs

of peritonitis. She was resuscitated with intravenous fluids

and intravenous antibiotics were started. Blood gases showed

metabolic acidosis. With a pre-operative suspicion of lower

esophageal perforation, the patient underwent exploratory

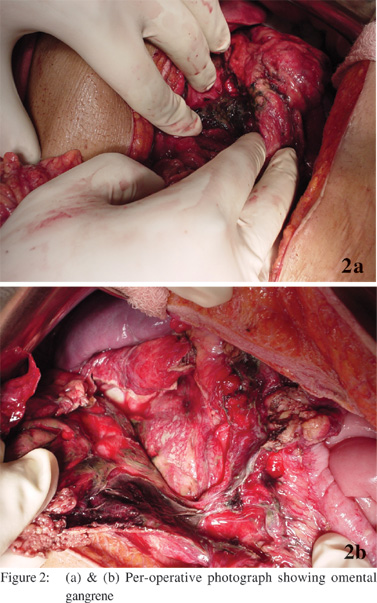

laparotomy. Per operative findings revealed dark hemorrhagic

foul smelling fluid with gangrenous omentum (Figures 2a & 2b) and no evidence of gastric or esophageal perforation. Stomach was small and contracted. Surgical procedure included

omentectomy, feeding jejunostomy, lavage and drainage. She

was kept on elective ventilation and was extubated after her

acidosis was corrected. Postoperatively she developed chest

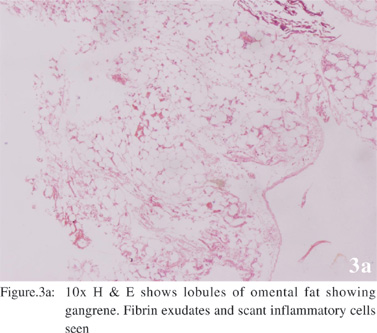

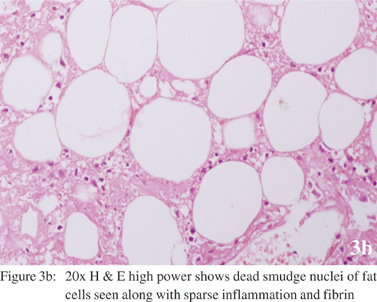

infection which was treated with antibiotics. She wasdischarged after 2 weeks. Histopathology showed lobule of

omental fat showing gangrene with fibrin exudates and few

inflammatory cells (Figures 3a & 3b). At 3-months follow up she is taking feed through jejunostomy and is being worked

up for definitive surgery.

Discussion

Primary omental torsion was first reported by Eitel in 1899 in

which a bulky and mobile greater omentum particularly on the right side twists around the distal right epiploic vessels with

subsequent venous occlusion, edema and arterial thrombosis leading to gangrene. Johnson[1] in 1932 first described, primary

omental infarction without torsion. The reported incidence is 0.1% of patients undergoing laparotomy for appendicitis.[2] The

incidence has been rising attributed to increased awareness of

the entity, technical advancements in imaging and utilization

of CT scan for evaluation of abdominal pain.

The exact etiology is not known. Predisposing factors

reported in the literature include variations in arterial supply to

the right side of the greater omentum, excess omental fat

associated with obesity (explaining its greater incidence in

adults), hypercoagulability, trauma, straining, vascular

congestion secondary to overeating, overexertion, and sudden

positional change.[3] Omental infarction in adults is rarely

described following intra-abdominal surgery, after marathon

running, with right-sided heart failure, or as a complication of

vasculitis[4].

To our knowledge this is the first case in which corrosive

ingestion has been the pathophysiological mechanism for the etiology of late omental infarction. The reason for late

development of omental gangrene following corrosive intake

is not known, but could possibly be related to the development

of thrombosis of the omental vessels resulting from inflamed contracted stomach following corrosive ingestion.

The right side of the omentum is affected in the majority of

patients leading to right sided abdominal pain. The right-sided predilection is usually attributed to anomalous right omental

vascular development.[5,6] It was predominantly left sided in our case, probably related to the etiology of gangrene. Other

symptoms include low grade fever and occasional vomiting. Leukocyte count may be mildly elevated.

Characteristic features[7,8] of omental infarction on imaging

may help in making a preoperative diagnosis in suspicious cases. The omental infarct on CT scan appears as an ovoid

area of high attenuated fat containing hyperattenuated streaks just beneath the parietal peritoneum with thickening of the

overlying anterior abdominal wall. Ultrasound scan shows the omental infarct typically appearing as a hyperechoic, noncompressible,

ovoid intra-abdominal mass adherent to the anterior abdominal wall with localized point tenderness.

Omental infarction usually follows a benign course that

allows conservative management. Spontaneous and complete

resolution of symptoms typically occurs within 2 weeks.

However non-operative treatment has a risk of leaving the

necrotic tissue inside, resulting in prolonged convalescence

due to gangrene or abscess formation. Omental abscess and

bowel obstruction are the delayed complications of omental

infarction.

Surgery is indicated in patients who have worsening of

symptoms on conservative management, in whom omental gangrene result in sepsis and when there is diagnostic dilemma.

Surgery usually results in early resolution of symptoms with little morbidity. Histology shows hemorrhagic infarction associated with fat necrosis, followed by cellular infiltration,

fibrosis and scar formation.

References

- Johnson AH. The great omentum and omental thrombosis.

Northwest Med. 1932;31:285–90.

- Lardies JM, Abente FC, Napolitano A, Sarotto L, Ferraina P.

Primary segmental infarction of the greater omentum: a rare cause

of RLQ syndrome; laparoscopic resection. Surg Laparosc Endosc

Percutan Tech. 2001;11:60–2.

- Rich RH, Filler RM. Segmental infarction of the greater omentum: a case of the acute abdomen in childhood. Can J Surg.

1983;26:241–3.

- Wiesner W, Kaplan V, Bongartz G. Omental infarction associated

with right-sided heart failure. Eur Radiol. 2000;10:1130–2.

- Ho CL, Devriendt H. Idiopathic segmental infarction of right sided greater omentum: Case report and review of the literature.

Acta Chir Belg. 2004;104:459–61.

- Mainzer RA, Simoes A. Primary idiopathic torsion of the omentum: Review of the literature and report of six cases. Arch

Surg. 1964;88:974–83.

- Puylaert JB. Right sided segmental infarction of the omentum:

clinical, US, and CT findings. Radiology. 1992;185:169–72.

- Karak PK, Millmond SH, Neumann D, Yamase HT, Ramsby G. Omental infarction: report of three cases and review of the

literature. Abdom Imaging. 1998;23:96–8.