48uep6bbphidvals|366

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Introduction

Defaecation remains an essential part of normal daily life. Its implication to health is very important as it is one of the means by which individuals excrete wastes from ingested food and other materials. Although diarrhoea and constipation are more commonly referred to in paediatric practice, not many studies have described the normal defaecation frequency and patterns in children and adolescents in Africa. The majority of the published studies were from the developed countries and involved the school age children.1,2,3,4,5,6,7 Studies from Nigeria were mainly in infants and children under the age of 5 years[8,9] as well as in adults,[10] leaving the adolescents scarcely investigated. Changes in bowel habits can be a frequent occurrence in daily life, and may be a pointer to colorectal diseases.[11,12,13,14,15] Thus, clarification of bowel habits within the general population is necessary not only for managing constipation and diarrhoeal diseases in children and adolescents but also for evaluating the relationship between defaecation and many other diseases such as those involving the colon and rectum.

The frequency of defication depends on many factors such as dietary fibres, infection, infestations, age and race[3,4,5,6,7] and may vary from place to place as well as person to person. It is now known that western life style significantly influences the food preparation and dietary habits of Nigerians, particularly the urban dwellers. With the increasing fast-food shops or restaurants in major Nigerian cities, there appears to be a shift from high residue diet to low residue mainly flour-based fast food among children and adolescents.[8] The changing dietary pattern portent a significant change in the bowel habits of Nigerian children and adolescents. Therefore it is not unlikely that there may be alteration in their bowel habits. In view of this, it is important for each region, even in the same country, to determine its own normal defecation pattern for different age categories such that deviation from normal may be recognized more readily and promptly treated. The present study therefore aimed at providing the normal reference values for the bowel habits of Nigerian adolescents resident in Ibadan, an urban city in south-west of Nigeria.

Methods

Study design

This was a prospective cross-sectional study of secondary school children residents in the Ibadan North Local Government Area (IBNLGA) of Oyo State, Nigeria. Participants were approached for consent in their respective secondary schools, and information was obtained over a 4 month period, from May to August, 2008.

Study location

IBNLGA is one of the 33 LGAs in the state, with an estimated size of 27,249 square kilometres, a mean annual rainfall of 1258.9 mm and an annual temperature of 26.6°C-28.8°C. The population of IBNLGA is 306,795 (Nigeria census 2006) and the people are mainly of the Yoruba ethnic group. Other ethnic groups in Nigeria are well represented but constitute the minority. There were 87 public and 24 approved private secondary schools in the study area as at the time of this study. The public schools are under the control of the Oyo State Government and mainly populated by the children from relatively low socioeconomic class. The private schools are owned by private individuals and are populated mainly by the children from families of relatively higher social class.

Sample size determination

Assuming about 50% of all study population would open their bowels at least once daily, an approximately 1100 school children were estimated as the minimum sample size to achieve an exact error rate of 2.79% at 95% level of confidence and power of 80%. This estimate (n=1100) was increased to 1300 to allow for non-response rate of 15%.

Sampling procedure

Using a two-stage stratified random sampling technique consenting apparently healthy secondary school children were enrolled. Chronically ill children such as children with sickle cell anaemia, physically handicapped children (those on wheel chair) or on any medication for any illness two weeks prior to the study were excluded. Two schools (one private and one public) were randomly selected from each of five zones in the IBNLGA using a computer-generated table of random numbers.

Using the school registers, a sampling frame was then made for male and female children in each school. Within each school, 130 students were randomly selected (using a computergenerated table of random numbers) from the list of their registers until a number over the calculated sample size for each school was obtained (bearing in mind the male:female ratio in each school). The schools were first visited and their respective principals and teachers were consulted. The purpose of the study and the protocol was explained to the students by one of the authors. After two weeks the schools were revisited for data collection. Written consent of each participant was sought, and if given, the child was enrolled otherwise the child was replaced by the next selected number.

Instruments and data collection procedures

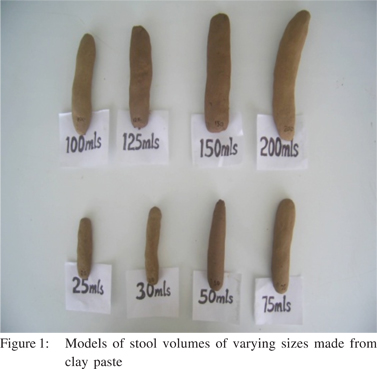

Using semi-structured questionnaire, information was obtained on family background, demography, diets in the preceding 2 days and daily bowel habits. Data were also collected on the modality and experience of participants during defaecation. Stool model of different volumes, made from clay paste was used to help the participants judge the size of their stools (Figure 1). Similarly, a colour chart was shown to each subject to choose the colour closest to his/her stool colour in the preceding 2 days. Those who did not make immediate estimation of their stool volumes or chose their stool colour from the displayed models and chart, were given two days to observe their stools and one of the authors went back the third day to collect the information from them. The questionnaire, stool model and colour charts were pretested and validated among 65 adolescents purposively selected from five secondary schools located in Ibadan North-East Local Government Area. The children who participated in the pretest were from similar secondary schools, age groups and socioeconomic background. The ambiguous questions and misunderstood model and colour charts were corrected before the data collection exercise at IBNLGA. Dietary Reference Intakes (DRI) for fibre table was used to classify foods intake into high or low class as published by Anderson et al.[18] For the purpose of this study, individuals with estimated dietary fibres less that 26 g/day and above 31 g/day were considered to have had low and high fibre diet respectively.

Data management and analysis

Data was entered and analyzed using the SPSS 11.0 for Windows (Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). The parents of the

study participants were stratified into five socioeconomic classes based on the criteria previously used by Oyedeji.[16] Categorical variables were compared using either the corrected Chi square test or Fisher’s exact test, while continuous variables were analyzed using the Student t test or analysis of variance (ANOVA). Continuous variable estimates were expressed as mean (±SD) or median while categorical variables were in proportions, ratios and percentages. Statistical significance level was set at p<0.05.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Oyo state Ministry of Health ethical review board.

Results

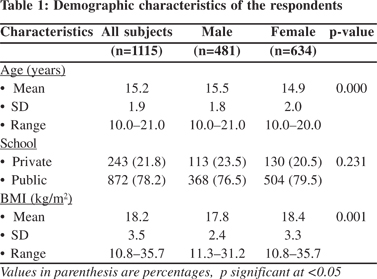

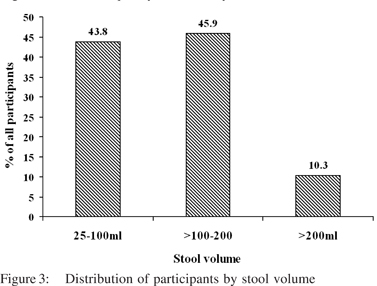

One thousand, three hundred participants were given questionnaires, but only 1115 returned their questionnaires

completed, giving a response rate of 85.8%. Further analysis was carried out on data from 1115 participants. There were 481 (43.1%) males and 634 (56.9%) females with a male to female ratio of 1:1.3. Eight hundred and seventy two (78.2%) were from public schools, while the remaining 243 (21.8%) were from the private schools, giving a ratio of 3.6:1 (Table 1). The age of the participants ranged from 10.0 to 21.0 years with a mean (SD) of 15.2 (±1.9) years, while the mean age of the male participants, 15.5 (±1.8) years was significantly higher than the mean age of 14.9 (±2.0) years for the females, p=0.000. The mean BMI (SD) 17.8 (±2.4) kg/m2 for the male participants was significantly lower than 18.4 (±3.3) kg/m2 for their female counter parts, p=0.001 (Table 1). Five hundred and eighty five (52.5%) participants belonged to the high social classes (I –II), while 530 (47.5%) belonged to the low social classes (III-V). All the participants were on a mixed diet made up of both high and low fibre diets. For breakfast, this comprised of food such as rice and beans (50.0%), bread with chocolate beverage(18.8%), beans and bread (18.1%), yam and stew (8.7%), Spaghetti and Indomie (1.2%), corn meal with bean cake (1.7%) and yam flour and soup (1.5%). The lunch and dinner were often similar and consisted of such foods as beans and rice (16.1%), bread and beans (10.2%) yam and stew (10.5%), Spaghetti and Indomie (0.9%), pap and baked beans (2.2%) and more bulky foods such as “Eba,” “foo foo” made from grated or fermented cassava and pounded yam or yam flour with soup (60.1%). The bulky foods were eaten with soup made of some green vegetables, tomatoes, onions, pepper and meat or fish. Fruits such as orange, mango, pawpaw, banana and pineapple were eaten ad lib depending on the season.

Stool frequency, volume and consistency

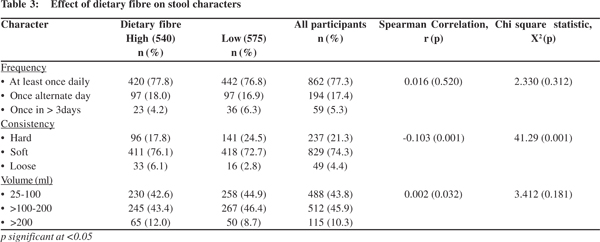

Eight hundred and sixty two (77.3%) participants opened their bowels at least once daily, 194 (17.4%) once in alternate days, and 59 (5.3%) once in >3 days (Figure 2). There was no age or gender difference in the stool frequency of the participants (p=0.141). The time of the day, participants opened their bowels varied widely: 752 (67.4%) of the participants opened their bowels at any time of the day, 208 (18.7%) opened their bowels only in the morning, 70 (6.3%) in the afternoon, 49 (4.4%) in the evening and 36 (3.2%) at night. There was no significant correlation between time of bowel opening and stool frequency (r=0.028, p=0.347).

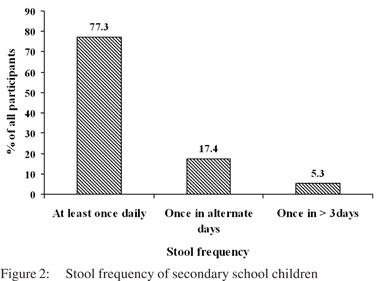

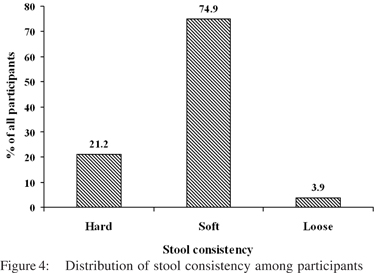

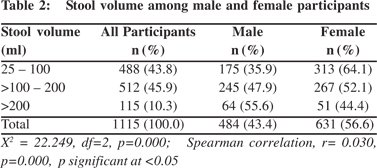

Overall, the stool volume of the participants ranged from 25 ml to > 200 ml. The stool volume of 488 (43.8%) participants ranged between 25 ml and 100 ml at each bowel opening, 512(45.9%) produced between >100 ml and 200 ml while 115 (10.3%) produced >200 ml stool (Figure 3). Relatively higher proportion of males (64) than females (51) produced >200 ml of stool per bowel opening. There was a significant correlation between stool volume and gender (p=0.000, r=0.030), (Table II). The most frequently reported stool consistency by 835 (74.9%) of the participants was soft stool, while hard and loose stool were reported by 237 (21.2%) and 43 (3.9%) participants respectively (Figure 4). However, among those 59 children who passed stool once in >3days, 25.4% of them passed hard stool while 74.6% passed soft stool (p<0.001). It has not been described separately whether they were passing hard stools. No age difference was observed in the stool consistency within different age groups.

Five hundred and sixty three (50.5%) participants reported that they usually passed brown stool while 516 (46.3%) and 36 (3.2%) reported that they passed yellow and greenish-brown stool respectively. Dietary fibre intake was similar among participants who opened their bowels either daily, in alternate days and once in >3days. Participants who passed stool once in >3days, comprised 4.2% and 6.3% of those high and low fibre diet respectively (p=0.312). Similarly stool volumes were not different among participants who were on high versus low fibre diets: passed 25-100 ml (42.6% versus 44.9%), >100-200 ml (43.4% versus 46.4%) and >200 ml (12.0% versus 8.7%); (p = 0.181). Conversely, passage of hard stool was significantly more common among participants on low (24.5%) compared with high (17.8%) fibre diets (p=0.001). Overall, 38 (3.4%) participants had passed blood in their stool at some time and this was commoner among those who were on low fibre diet, opened their bowels infrequently and passed hard stool.

The proportion of participants from the high social classes I and II (66.1%), with infrequent bowel opening was significantly higher than 33.9% from the low social class, (p=0.048). There was a significant correlation between stool frequency and social class, (p=0.048, r=0.072, p=0.016). Infrequent bowel opening was reported more among participants who did not have toilet facility at home (8.9%) than those who had one form of toilet facility or the other (4.6%) however, this was not significant, (p=0.344).

Discussion

This study has shown that apparently healthy Nigerian adolescents display a wide range of bowel habit, opening their bowels from at least once daily to once every other day and passing between 25 and >200 ml of mostly soft stool. This is similar to observations among preschool children in Nigeria[8], Britain[1], Yoruba adults[10] and medical students in same study area by Olubuyide et al.[17] As many as one out of twenty participants opened their bowels once in more than three days. This proportion may be a reflection of the magnitude of asymptomatic constipation among healthy population in Nigeria.

Many other studies have shown that bowel frequency decreases with increasing age in infancy and preschool periods,[19,20] and remains stable among the adolescents and adults.[15, 21] However, the present study showed no correlation between age and frequency of bowel motions. This lack of correlation was previously reported among Nigerian adults.[10] Similar observation was reported by Weaver and Steiner[1], Akinbami et al[8] and Olubuyide et al.[17] This may be because the majority of the participants in this study were in the pubertal age and as such may be under the influence of the same physiological factors such as hormonal effect. For instance in women, bowel opening varies between periods of menstruation and no menstruation, and also during pregnancy.[22,23,24,25,26]

A significantly higher proportion of participants in high social class passed stool once in more than three days compared with those in low social class. The reason for the occurrence of more infrequent bowel opening among the high socioeconomic class is not readily clear. There was no significant association between dietary fibre intake and social class. Overall, it was observed from this study that irrespective of the social class, low fibre diet consumption was more common among those who opened their bowels infrequently. This is similar to other reports in which low fibre diet was associated with infrequent bowel openings.[27, 28] However, other studies have shown no significant association between daily dietary fibre intake and stool frequency among adolescents.[29, 30] In a review of 34 studies low socioeconomic status has been shown to be a risk factor for constipation contrary to present study.[31]

The majority of participants from the present study produced between 25-200 ml of stool per bowel motion. In addition the dietary fibre intake was related to the stool volume and consistency in this study. This is similar to the finding by Akinbami et al,[8] who reported average stool volume of 50-75 ml passed by under 5 children who were on predominantly high fibre diet, but in contrast with the report of Weaver and Steiner1 on British children who were predominantly on low fibre diet and passed 25 ml of stool. However, no significant correlation was found in this study between stool volume and frequency of stool. In the tropical countries stool volume up to 400 ml has been considered as the normal, but in the present study stool volume >200 ml was taken as upper limit because none of the participants had history of recent diarrhoea (defined as more than three loose bowel motion a day) and very few number of participants in the present study reported stool volume close to this upper limit of normal. Therefore no further effort was made to quantify the actual stool volume of the study participants. Many factors have been implicated in the regulation of bowel opening and volume of stool. It is important to note that epidemiological studies have shown that in countries where starchy food dominate their diet such as in Nigeria, relatively large volume of stool may be passed on defaecation as 8-10% of starch escapes absorption.[29]

Supplementation of diet with fibre has been observed to improve bowel function with reduced stool frequency but with increased stool volume.[30]

Majority of the participants in the present study passed either brown or yellow stool. There was no correlation between stool colour and dietary fibre intake. The stool colours reported by participants in this study are similar to those reported in previous studies.[31,32,33,34] Dietary fibre in take also correlated wellwith stool consistency such that participants on low fibre diet tended to pass hard stool more frequently. This agrees with the findings of other workers.[1,8,10] Diet, especially the fibre content has been observed to be the prime factor in the regulation of bowel habit, although the mechanism is not very clear. Cummings[35] observed that the effect of dietary fibre on bowel movement is related to its physico-chemical properties.

Fibre, by virtue of its large particles and relatively slow degradation in the colon, retains water in the gut and increases the faecal bulk. Increasing bulk also stimulates colonic movements, thus aiding defaecation.[36] In addition, fibre promotes microbial growth within the colon, thereby increasing the bacterial content of faeces which accounts for 30-40% of the dry weight of stool. Although, most of the Nigerian stable foods eaten by the children in this study have been more refined in recent years when compared to those eaten by children studied by Akinbami et al,[8] and Lewis and Kale[10] in Ibadan and Igbo-Ora respectively, they still have a relatively high fibre content unlike the highly refined, low fibre diet eaten by many British children.[1] This may explain the higher rate of bowel motility and greater frequency of defaecation by the Nigerian child. It is also not surprising that the Nigerian child passes a larger stool than the British child,[1] dietary fibre also influences the size and consistency of stools.

Three percent of the children who participated in this study had passed blood in their stool at some time. This is comparable with the 2% reported from South Africa[4] but much lower than 9% obtained from the British children.[1] The present study showed a significant correlation between gender and stool volume, as more females passed smaller stool volumes in contrast with their male counterparts who passed larger stool volumes. The possible factors responsible for this finding were not explored in this study. We have not tried to correlate the frequency and volume of defecation with perception of participants about it. Infrequent bowel opening was commoner among participants who did not have toilet facility at home compared to those who had toilet facility irrespective of the type. The factors responsible for this were not evaluated in this study. Woodmansey[37] observed that some children may suppress the urge to defaecate as a result of change in the environment, particularly when they travel out of their place of residence. Unavailability of toilet facilities when the urge to defaecate occurs, leads to delay in evacuation of stool with subsequent hardening of the stool accompanied by straining during defaecation. Shigeyuki et al,[38] also observed travelrelated changes in bowel habits among the Japanese general population with complaints of constipation. The infrequent opening of the bowel observed among this group of Japanese, could be attributed to the new environment, strange toilet facilities and the unavailability of adequate functioning toilet facilities. It is believed that the data from this study may serve as bowel habit reference values for the Nigerian adolescents and that it will be of use to health workers in the early recognition of diarrhoea and constipation. The observations from this study are also expected to serve as a reference for comparison with studies from other developing countries where the diet may also be of mixed fibre content.

References

1. Weaver LT, Steiner H. The bowel habit of young children. Arch Dis Child. 1984;59:649–52.

2. Weaver LT, Ewing G, Taylor LC. The bowel habit of milk-fed infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1988;7:568–71.

3. Weaver LT, Lucas A. Development of bowel habit in preterm infants. Arch Dis Child. 1993;68:317–20.

4. Walker A WB. Bowel behaviour in young black and white children. Arch Dis Child. 1985;60:967–70.

5. Weaver LT. Bowel habit from birth to old age. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1988;7:637–40.

6. Harari D, Gurwitz JH, Avorn J, Bohn R, Minaker KL. Bowel habit in relation to age and gender. Findings from the National Health Interview Survey and clinical implications. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:315–20.

7. Sandler RS, Drossman DA. Bowel habits in young adults not seeking health care. Dig Dis Sci. 1987;32:841–5.

8. Akinbami FO EO, Akinwolere OA. Defaecation pattern and intestinal transit in Nigerian children. Afr J Med Med Sci. 1995;24:337–41.

9. Adegboye OA OA, Adeniyi A. Bowel habits of preterm infants in Ilorin. Nig J Paediatr. 2003;30:50–3.

10. Lewis EA, Kale OO. Bowel habit in a Yoruba rural community: preliminary report. Afr J Med Med Sci. 1978;7:157–61.

11. Ani AN. Anorectal diseases in western Nigerian adults. A field survey. Dis Colon Rectum. 1983;26:381–5.

12. Painter NS, Truelove SC, Ardran GM, Tuckey M. Segmentation and the localization of intraluminal pressures in the human colon, with special reference to the pathogenesis of colonic diverticula. Gastroenterology. 1965;49:169–77.

13. Munakata A, Nakaji S, Takami H, Nakajima H, Iwane S, Tuchida S. Epidemiological evaluation of colonic diverticulosis and dietary fiber in Japan. Tohoku J Exp Med. 1993;171:145–51.

14. Burkitt D. Possible relationships between bowel cancer and dietary habits. Proc R Soc Med. 1971;64:964–5.

15. Burkitt DP, Walker AR, Painter NS. Effect of dietary fibre on stools and the transit-times, and its role in the causation of disease. Lancet. 1972;2:1408–12.

16. Oyedeji GA. Socio-economic and cultural background of hospitalized children in Ilesha. Nig J Paediatr. 1985;12:111–7.

17. Olubuyide IO, Olawuyi F, Fasanmade A. Frequency of defaecation and stool consistency in Nigerian students. J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;98:228–32.

18. Anderson J, Perryman S, Young L, Prior S. Dietary fiber. Food and Nutrition Series. Available from: http://www.ext.colostate.edu/ pubs/foodnut/09333.pdf

19. Osatakul S, Yossuk P, Mo-suwan L. Bowel habits of normal Thai children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1995;20:339–42.

20. Tham EB, Nathan R, Davidson GP, Moore DJ. Bowel habits of healthy Australian children aged 0-2 years. J Paediatr Child Health. 1996;32:504–7.

21. Dimson S. Carmine as an index of transit time in children. Arch Dis Child. 1970;45:232–5.

22. Ohlsson B. Bowel habits in women during pregnancy, breast feeding, and after breast feeding. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:224–5.

23. Fukuda S, Matsuzaka M, Takahashi I. Bowel habits before and during menses in Japanese women of climacteric age: a population based study. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2005;206:99–104.

24. Celik AF, Turna H, Pamuk GE, Pamuk ON. How prevalent are alterations in bowel habits during menses? Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:300–1.

25. Ohlsson B. Bowel habits in women during pregnancy, breast feeding, and after breast feeding. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:224–5.

26. Celik AF, Turna H, Pamuk GE, Pamuk ON. How prevalent are alterations in bowel habits during menses? Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:300–1.

27. Guimaraes EV, Goulart EM, Penna FJ. Dietary fiber intake, stool frequency and colonic transit time in chronic functional constipation in children. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2001;34:1147–53.

28. Zaslavsky C, da Silveira TR, Maguilnik I. Total and segmental colonic transit time with radio-opaque markers in adolescents with functional constipation. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998;27:138–42.

29. Stephen AM. Starch and dietary fibre: their physiological and epidemiological interrelationships. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1991;69:116–20.

30. Vandewoude MF, Paridaens KM, Suy RA, Boone MA, Strobbe H. Fibre-supplemented tube feeding in the hospitalised elderly. Age Ageing. 2005;34:120–4.

31. Peppas G, Alexiou VG, Mourtzoukou E, Falagas ME: Epidemiology of constipation in Europe and Oceania: a systematic review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2008;8:5.

32. Myo-Khin, Thein-Win-Nyunt, Kyaw-Hla S, Thein-Thein- Myint, Bolin T. A prospective study on defecation frequency, stool weight, and consistency. Arch Dis Child. 1994;71:313–4.

33. Bharucha AE, Seide BM, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ, 3rd. Insights into normal and disordered bowel habits from bowel diaries. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:692–8.

34. Gabrio B, Massimo B, Fillippo P, Renato B, Antonio B. An extended assessment of bowel habits in a general population. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:713–6.

35. Cummings J. Constipation, dietary fibre. Post Grad Med J. 1984;60:811–9.

36. Irving MH, Catchpole B. ABC of colorectal diseases. Anatomy and physiology of the colon, rectum, and anus. BMJ. 1992;304:1106–8.

37. Woodmansey AC. Emotion and the motions: an inquiry into the causes and prevention of functional disorders of defecation. Br J Med Psychol. 1967;40:207–23.

38. Nakaji S, Matsuzaka M, Umeda T, Shimoyama T, Sugawara K, Sakamoto J, et al. A population-based study on defaecatory conditions in Japanese subjects: methods for self valuation. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2004;203:97–104.