48uep6bbphidvals|342

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Bronchial asthma (BA) is a chronic inflammatory condition of the airways characterised by bronchial hyper-responsiveness and narrowing of the airways, which is reversible either spontaneously or with treatment. It affects about 300 million people worldwide including 10% of the Nigerian population.[1] Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) however is a chronic gastrointestinal condition characterised by abnormal exposure of the mucosa of the lower oesophagus to acid due to dysfunction of the lower oesophageal sphincter. About 10-30% of adult population in the Western world are affected.[2]

GERD can aggravate asthma in several ways; and these include vagally mediated reflex triggered by acid in oesophagus as well as micro aspiration of gastric acid resulting in bronchoconstriction.[3] Also some asthma drugs cause lower esophageal sphincter relaxation making acid escape easy. Hyperinflation of the chest in asthma with flattening of the diaphragm is thought to contribute to weakness of the crura muscles and dysfunction of the lower esophageal sphincter and amplification of the thoraco-abdominal pressure gradient during an attack helps to promote GERD.[4]

Reflux symptoms are reported in up to 77% of asthmatics while 32-82% of asthmatics have abnormal pH studies. Silent reflux may be as common as symptomatic reflux with reports suggesting that 25-50% asthmatics have no reflux symptoms but abnormal pH studies[5]. On the other hand, GERD has been known to have extra-oesophageal manifestation including hoarseness of voice, cough and wheezing.[6] Endoscopic studies equally could be normal in up to 50% (non-erosive GERD).[7]

There appears to be a diagnostic dilemma, which is further intrigued by cases of silent GERD. 24-hour oesophageal pH measurement and sometimes manometry has remained the cornerstone of GERD diagnosis, however, this is often not widely available in daily practice because of their cost and invasive nature. Hence, guidelines for their use[8] have been published. Symptom analysis however has been documented as a practical and inexpensive method of diagnosing GERD, but this obviously may not detect cases of silent GERD or with atypical symptoms. A number of validated questionnaires including QUEST, REQUESTTM and FSSG[9] exist with differing sensitivity and predictability.

Reports of relationship between BA and GERD exist in Western literature with sometimes conflicting findings to improper definition of BA and/or GERD.[10,11,12] There is limited information about this association among asthma sufferers in Nigeria. We aim to study this relationship among our patients to bridge the existing gap with objectives as: to determine the frequency of symptomatic GERD among previously diagnosed asthmatics attending an Asthma clinic by means of a validated questionnaire (frequency scale for symptoms of GERD (FSSG or Fscale)[9] as well as 24 hour nasopharyngeal DX PH detector, to compare GERD prevalence between the asthmatics and a control population matched for age and sex and to document the upper gastrointestinal tract endoscopic findings in the subgroup of subjects found to have GERD.

Methods

This was a descriptive study carried out at the Asthma clinic of Lagos state university teaching hospital (LASUTH) Ikeja for a period of three months. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institution’s Research and Ethics committee in August 2007 before commencement of the study in September 2007. BA diagnosis was based on the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Expert Panel Report.[10]

Other Inclusion criteria included adult patients above 15 years of age, with absence of co-morbidities like diabetes, hypertension, heart failure, significant tobacco use and chronic obstructive airway disease. The control group was recruited from the hospital workforce and medical trainees that had no history of asthma and were free from the aforelisted comorbidities.

All recruited subjects gave a written informed consent before participation. An interviewer administered questionnaire collected information on socio demographic characteristics, asthma symptoms and duration of diagnosis as well as scoring for GERD symptoms using the F-scale.[9]. This is a 12-item questionnaire which utilises both symptom description and its frequency, developed from a cohort of endoscopy proven GERD patients and revalidated in another group of GERD and non-GERD patients. Anthropometrics indices as well as spirometry were done using the digital spirometer, which measures forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) as well as peak expiratory rate (PEFR) (for asthmatics).

Subjects with F-Scale >7 were classified as having GERD and were invited to undergo a 24 hour pH study using a new nasopharngeal pH probe[13] (DX-PH) from RESTECH California, USA as well as an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy examination. The new pH probe utilised in this study is minimally invasive and measures both the pH of aerosolised, humidified refluxate and traditional liquid events. Unlike traditional probes it does not require immersion in liquid foraccurate reading and can be easily inserted transnasally in the office. The 1.5m thick probe shaft is attached to a small transmitter, which communicates wirelessly with a recorder worn at the patient’s waist. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed after an overnight fasting using an Olympus videoscope (model CLV 140 processor). Local xylocaine spray was used as topical anaesthetic while atropine and diazepam were premedication. Consent was sought and obtained before these procedures.

All data were collated and subjected to analysis using Microsoft SPSS software. Comparison was done using chisquare and expression of qualitative and quantitative data as means, proportion and percentages.

Results

Ninety-eight asthmatics (mean age (SD) 39.8years (17) and male: female ratio of 1:1.5) were studied. There were 78 controls with a mean age of 34±12 and male to female ratio of 1:1.8.

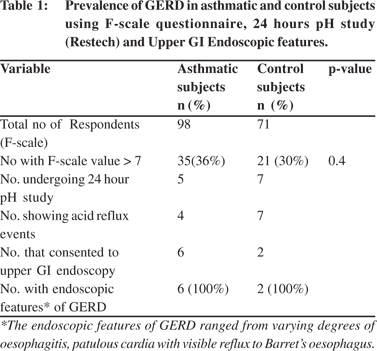

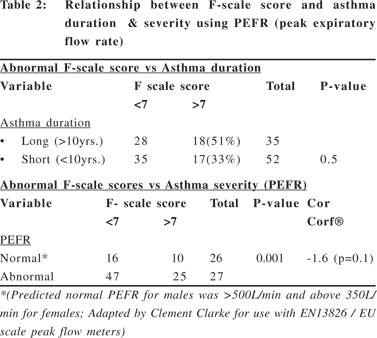

The prevalence of GERD using the F-scale in the asthma group was 36% and 30% in the control (P=0.4). This did not show any statistical difference in the prevalence of GERD in the two groups studied (Table 1). The prevalence of GERD appears not to be related to duration of asthma but to asthma severity as measured by PEFR (p=0.001, Cor. Coef. -1.6) (Table 2).

Five asthmatics and 7 control subjects with F scale of >7 underwent a 24-hour PH study. Four of the asthmatics and all 7-control subjects showed abnormal acid reflux events in the study (Table 1). Only 8 (72.7%) of the subjects with GERD having Fscale >7 (6 asthmatics and 2 controls) agreed to upper gastrointestinal endoscopic examination; and they all showed evidence of GERD ranging from varying degrees of oesophagitis, patulous cardia with visible reflux to barrets oesophagus (Table 1).

Discussion

The relation between GERD and BA continues to be subject of research and discourse. Our study has not shown any significant difference in the prevalence of symptomatic GERD among a population of previously diagnosed asthmatics (36%) and another control population of non-asthmatics (30%). The prevalence rate of symptomatic GERD in this study is in keeping with previous reports.[11,12] The asthmatics were already diagnosed based on typical history of recurrent symptoms and reversible obstructive pattern on lung function test while GERD was diagnosed using a validated questionnaire (FSSG) with sensitivity of 62% and specificity of 59% using a cut-off of 8 as was used in the present study. The diagnosis of GERD was further corroborated by the findings of abnormal acid exposure on the 24-hour PH study in 92% of those positive on questionnaire that volunteered to undergo the pH study. One of the subjects was positive on the symptom scale, however, the subject had a normal acid study. The findings of the DXpH probe used in this study had been found comparable to conventional pH recorders in previous studies.[13]

Previous reports[11,12] had indicated a higher prevalence of GERD among asthmatics than a control population. In the study by Chopra et al,[11] the sample size of the study subjects and control (80 versus 10 respectively) were not matched and scintiscan method used for GERD detection had a low specificity. The longitudinal study by Ruigomez et al[12] showed a small but significant increase in relative risk of incident diagnosis of GERD among patients with new diagnosis of asthma. The diagnosis of GERD and asthma relied on the records of the general practitioners (GP) as the study-entailed extraction of data from UK general practice research database.

The diagnostic criteria of these conditions by the various GP are not standardized.

Among the asthmatics, the prevalence of GERD appears not to be related to duration of asthma but to asthma severity as measured by PEFR (p=0.001, Cor. Coef. -1.6). The explanation for this observation is possibly related to the previously reported[4] mechanisms of micro aspiration and vagally mediated bronchoconstriction due to presence of acid in the oesophagus in GERD.

All eight subjects that underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy had endoscopic evidence of reflux which is in keeping with earlier reports[14] that combination of symptoms and endoscopic changes are highly specific (97%) for GERD (confirmed with pH testing). One shortcoming of this present study was the relatively fewer number of subjects consenting to do the pH study despite its availability and minimally invasive nature of this device.[13] This may relate to cultural beliefs and attitude toward research. These subjects (except one) had evidence of acid reflux on ambulatory pH, which further confirms the findings on symptom questionnaire. Equally PEFR (peak expiratory flow rate) has a lot of limitations in assessing asthma severity; as readings of up to 100 L/min lower than predicted in men and 85L/min in women are within normal limits.[15]

In conclusion, a higher prevalence of GERD among BA subjects than a control population is noted, but this difference was not significant. Further studies involving a larger sample size are required to validate this finding.

Acknowledgements

We wish to express our sincere appreciation to Respiratory Technology (RESTECH) of California for providing us the D-X PH ambulatory device used in the present study.

References

1. ISAAC steering committee. Worldwide variation in prevalence of asthma and allergies: the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC). Eur Respir J. 1998;12:315–35.

2. Dent J, Brun J, Fendrick AM. An evidence-based appraisal of reflux disease management —the Geneval Workshop Report. Gut. 1999;44:S1–16.

3. Morice AH. Gastro-oesophageal reflux and tachykinins in asthma and chronic cough. Thorax. 2007;62:468–9.

4. Sifrim D., Holloway R, Silny J, Xin Z, Tack J, Lerut A, et al. Acid, nonacid, and gas reflux in patients with gastroesopgageal reflux disease during ambulatory 24-hour pH- impedance recordings. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1588–98.

5. Mansfield LE. Gastroesophageal reflux and respiratory disorders: a review. Ann Allergy. 1989;62:158–63.

6. Johanson JF. Epidemiology of esophageal and supraoesophageal reflux injuries. Am J Med. 2000;108:99S–103S.

7. Fass R, Fennerty MB, Vakil N. Nonerosive reflux disease-- current concepts and dilemmas. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:303–14.

8. Hirano I, Richter JE; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. ACG practice guidelines: esophageal reflux testing. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:668–85.

9. Kusano M, Shimoyama Y, Sugimoto S, Kawamura O, Maeda M, Minashi K, Kuribayashi S, et al. Development and evaluation of FSSG: frequency scale for the symptoms of GERD. J Gastroenterol. 2004:39:888–91.

10. National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. Expert Panel Report 3, 2007. Bethesda, MD, NIH, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Pub. 08–4051.

11. Chopra K, Matta SK, Madan N, Iyer S. Association of gastroesophageal reflux (GER) with bronchial asthma. Indian Pediatr. 1995;32:1083–6.

12. Ruigómez A, Rodríguez LA, Wallander MA, Johansson S, Thomas M, Price D. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and asthma: a longitudinal study in UK general practice. Chest. 2005;128:85–93.

13. Ayazi S, Lipham JC, Hagen JA, Tang AL, Zehetner J, Leers JM, et al. A new technique for measuring of pharyngeal pH: normal values and discriminating pH threshold. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1422–9.

14. Tefera L, Fein M, Ritter MP, Bremner CG, Crookes PF, Peters JH, et al. Can the combination of symptoms and endoscopy confirm the presence of gastroesophageal reflux disease? Am Surg. 1997;63:933–6.

15. Nunn AJ, Gregg I. New regression equations for predicting peak expiratory flow in adults. BMJ. 1989;298:1071–2.