48uep6bbphidvals|337

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Chronic pancreatitis (CP) is a condition characterized by irreversible destruction and fibrosis of the exocrine parenchyma leading to exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and progressive endocrine failure leading to diabetes.[1] CP is a common problem with a prevalence varying from 10-125/100,000 population.[2,3,4] Chronic alcoholic pancreatitis is the commonest type of CP seen in the western population, while in the tropics there is a distinct non-alcoholic type of CP of uncertain etiology which is far more prevalent and is known as tropical pancreatitis (TP).[1] TP can be defined as a juvenile form of chronic calcific nonalcoholic pancreatitis prevalent almost exclusively in the developing countries of the tropical world. Some of its distinctive features are younger age of onset, presence of large intraductal calculi, an accelerated course of the disease leading to the end points of diabetes and/or steatorrhea and a high susceptibility of pancreatic cancer.[5,6,7] Recent work has focused on the role of genetic mutations in the etiopathogenesis of TP, but other factors such as nutritional, environmental and autoimmune have also been suggested[8,9] Since poverty and malnutrition were common in the countries from where the disease had been reported,[10,11] malnutrition was suspected as a causative factor in the development of TP.[12] The earlier reports on TP were from Southern India describing that most patients with TP were undernourished, implicating malnutrition as a cause of TP.[13,14,15] However, malnutrition could be the result rather than the cause of the disease since CP with consequent malabsorption could itself lead to malnutrition. We, therefore, conducted a case-control study to elucidate whether malnutrition was the causative factor of TP in patients belonging to Southern India.

Methods

Patients

All consecutive patients with CP attending Asian Institute of Gastroenterology, a single specialty large referral centre, between May 2007 and December 2008 were enrolled and diagnosis of CP was made based on the following criteria:[16]

Pancreatic calcification on plain x-ray of the abdomen, Ultrasonography (USG) or computed tomography (CT) scans showing pancreatic calcification and/or pancreatic ductal dilation and Endoscopic retrograde pancreatography (ERP) showing irregularity and/or dilation of the main pancreatic duct and/or pancreatic duct side branches, and/or presence of pancreatic stones/strictures. The etiology of chronic pancreatitis was determined as: Alcoholic CP- if a patients has been drinking more than 80g alcohol per day for greater than 5 years,[17] Tropical pancreatitis: if no definite cause was identified and miscellaneous CP: Other causes of CP such as hyperparathyroidism, obstruction and trauma were grouped under miscellaneous etiologies.

Patients were included in the study based on the following criteria: Etiology of chronic pancreatitis identified as TP and patients with disease duration of less than 1 year. Patients were excluded from the study for the following reasons: patients with acute exacerbation of CP, patients with CP of other etiologies (alcoholic CP and miscellaneous CP), patients with co-existing diseases such as alcoholic liver disease, renal failure, pancreatic cancer, tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS and pregnant women. Healthy individuals (n=101) who were age, sex and socio-economic status matched were included as controls from among those who came to the institute for routine health check up.

Nutritional Assessment

All patients and controls underwent detailed nutritional assessment which comprised of the following:

Anthropometric measurements

Anthropometric measurements included height, body weight and body mass index (BMI). Body weight and BMI included the previous body weight (body weight before onset of CP), present body weight (body weight after disease onset) and the weight loss. BMI was calculated by using the formula weight (kg)/height (m)[2]. BMI was classified as: Low BMI (<18.5 kg/m2) – indicating malnourished participants; Normal BMI (18.5-24.9 kg/m2) – indicating well nourished participants; High BMI (>25 kg/m2) – indicating overweight and obese Participants

Dietary Assessment

All the participants were interviewed by the clinical nutritionist regarding their dietary intake before and after the disease onset.

The educational and socio-demographic profile was also recorded. A semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire was used to collect nutrient and dietary information on the food groups and miscellaneous food items.

The questionnaire included the following:

1. Foods consumed during the day, before and after the disease onset.

2. Food items consumed weekly or monthly

3. Alcohol intake, if consumed

4. Types and amounts of oils used

5. Reasons for avoiding food intake after the disease onset

Daily intake of nutrients and foods were estimated by summing up all the raw foods consumed. Nutrient calculation (calories, percentage of carbohydrates, proteins and fats) from raw foods was done using standard nutrient values of Indian foods.[18]

Weight Loss and its possible causes

Patients were considered to have lost weight after the onset of TP if their weight decreased by 10% or more of the previous body weight.

The following potential causes of weight loss were analyzed:

1. Dietary Restriction: This was assessed by analyzing the dietary restrictions following the onset of TP with regard to calorie and nutrient intake.

2. Diabetes: The presence and duration of diabetes were noted. The diagnosis of diabetes was made using WHO guidelines; fasting plasma glucose of > 126 mg/dl and 2hr postprandial plasma glucose of >200 mg/dl was taken as indicative of diabetes mellitus.[7]

3. Abdominal pain and other gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms: As pain, nausea, vomiting and early satiety may result in restriction of food consumption by the patients, these were recorded as a possible causes of reduced dietary intake leading to weight loss.

Outcome Measures

The relationship between malnutrition and cause of TP was assessed by taking into consideration the previous (before TP) and the present body weights of the patient, weight loss after the onset of TP, the dietary intake before and after the diagnosis of disease, and comparison of previous body weight and BMI of patients with that of controls. Malnutrition was considered as an etiological factor to the development of TP if the previous weight and BMI of patients before the disease onset were significantly less than that of healthy controls.

Ethics

An informed consent was obtained from the patients and controls and the study protocol was approved by the institutional review board.

Statistical analysis

Mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for all the anthropometric and dietary parameters. Student t-test and chisquare tests were used to assess the quantitative and qualitative data respectively. SPSS program, version 14.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago; IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis and a p value less than 0.05 was considered significant in all the analysis.

Results

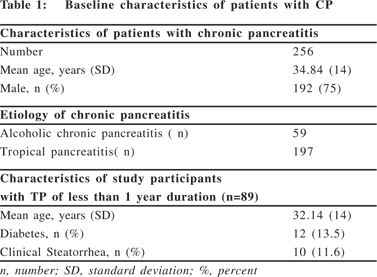

A total of 256 consecutive patients with CP were included in the study from May 2007 to December 2008. Their mean age was 34.84 ± 14 years. There were 192 (75%) males. Of 256 patients with CP, 77% (n=197) had TP and 45% (n=89) had TP with less than 1 year of disease duration. The mean age of study participants was 32.14 ± 14 years and 60 of them were male (Table1). Presence of diabetes and clinical steatorrhea was observed in 13.5% and 11.6% of TP patients.

Comparison of previous nutritional status of TP patients with controls

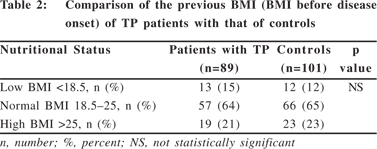

On the basis of the previous BMI (BMI before TP) of the patients, the nutritional status of the patients was comparable with that of controls (Table 2). There was no significant difference between the BMI of healthy controls and TP patients before the disease onset suggesting that malnutrition could not be the causative factor for the development of TP. The average calorie intake of the controls was 1376 ± 123 kcal per day which was similar to the calorie intake of TP patients before disease onset (p = 0.067).

Comparison of nutrition status of TP patients before and after the disease onset

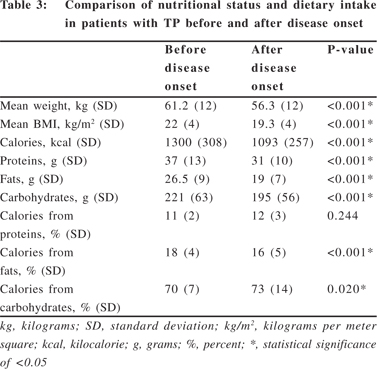

Most patients with TP had a BMI either in the normal range (n= 57, 64%) or in the high BMI category (n= 19, 21%) and only a minority of patients (15%) were underweight before the disease onset (Table 2). However, after the onset of TP, of the 57 patients with the normal BMI, 60% (34/57) became malnourished with BMI <18.5 and of the 19 overweight patients, BMI decreased to <25 kg/m2 in 53% (10/19) due to weight loss. Thus, the percentage of malnourished patients increased from 15% to 38% and that of overweight patients decreased from 21% to 11% (p <0.001) indicating that there was significant weight loss after the disease onset (Table 3).

Comparison of dietary intake of patients with TP before and after the disease onset

There was a significant reduction in the calorie, protein, fat and carbohydrate intake in patients with TP after the disease onset (Table 3). The percentage distribution of calories into nutrients showed significantly lowered percentage of calories from carbohydrates and fats (p <0.05). Patients were asked about their dietary restrictions and it was observed that 63% were restricting oil and other forms of fats (clarified butter, cheese, high fat milk, non-vegetarian foods and margarine). On questioning them for the reasons for restricting their dietary intake, it was observed that 62% restricted calorie and nutrient intake for the fear of abdominal pain and 38% restricted their dietary intake for abdominal pain, nausea, early satiety and other GI symptoms.

Weight loss and causes of weight loss in patients with TP

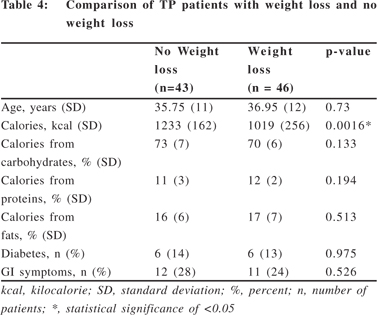

52% (46/89) of patients lost weight after the onset of TP. Patients who lost weight were compared with those who did not. The causes of weight loss that were evaluated were consumption of lower calories, presence of diabetes, GI symptoms such as pain which could contribute to decreased dietary intake. It was seen that patients who lost weight consumed significantly lower calories than those who did not (p = 0.0016, 95% CI, 86.81-343.19). However, there was no statistical significance in presence of diabetes and GI symptoms in patients who lost weight and in those who did not lose weight (Table 4), indicating that diabetes and GI symptoms were not independently related to weight loss in this study.

Discussion

There is a paucity of data on the nutritional profile and etiopathogenesis of TP. TP is a variant of CP of unknown etiology, occurring mostly in developing countries of tropical regions and TP is suggested to be the result of environmental gene interaction.[19,20] Clinical and epidemiological evidence have suggested malnutrition as a cause of TP,[17] though there are no reports so far to prove that malnutrition is the causative factor of TP. In the present study, we observed that 76% of patientswere normally nourished (normal BMI) or overweight (high BMI) before the onset of TP, and their nutrition status was comparable to that of the controls. We also observed that most patients (52%) lost weight after the onset of TP and the nutrition status significantly declined when compared to that before disease onset. This suggests that malnutrition could be the result and not a cause of TP. Malnutrition could be due to abdominal pain, sitophobia, nausea, vomiting, post prandial satiety and gastric dysmotility which contribute to decreased nutrient intake.[21] One potential limitation of the study, however, could be that determining the disease onset based on the actual diagnosis is inaccurate as the symptoms could have been persisting even before the precise diagnosis of TP.

Earlier reports on role of malnutrition in the etiology of TP was based on the observations that TP affects the poor population of developing nations and it is indeed true that protein-calorie malnutrition (kwashiorkor) was present in many TP patients.[1,8,22] However, it has been seen that kwashiorkor seldom leads to permanent pancreatic damage and pancreatic stones are absent even in advanced stages of kwashiorkor,[1] suggesting that protein-calorie malnutrition cannot be considered as an etiological factor of TP. There is also a possibility of deficiency of certain micronutrients that might be responsible for onset of TP,[23] which has not been analyzed in this study.

It has been reported that the clinical presentation of TP has changed over the past decade probably due to socio-economic, dietary and lifestyle modifications with older age of disease onset, prevalence in normally nourished individuals, milder pain and diabetes and increased longevity.[19,23] Similar to these findings, we also observed that the mean age of onset was ~32years and most of the patients (76%) were well nourished with BMI >19.5 kg/m2 before the disease onset, indicating that malnutrition is not a cause of TP.

More than half of the patients lost weight after the onset of TP (52%) and hence we analyzed the contributing factors of weight loss in TP patients. Low calorie consumption was an independent factor contributing to weight loss in these patients. However, when the percent of calories from carbohydrates, proteins and fats was analyzed between patients who lost weight and those who did not, there was no significant difference in percent of macronutrient intake. This explains that all patients with TP decreased the carbohydrate, protein and fat consumption leading to decreased calorie intake which contributed to weight loss in those patients who consumed significantly lesser calories than others. Although, diabetes has been shown to be an independent risk factor for weight loss in patientswith TP,[23] our study did not reveal presence of diabetes in TP patients as a risk factor for weight loss. Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency as evidenced by clinical steatorrhea was observed only in 11.6% of ourTP patients and the presence of maldigestion due to exocrine pancreatic insufficiency was not shown to be an independent risk factor for weight loss in our study.

In conclusion, this study suggests that malnutrition is not an etiological factor for tropical pancreatitis and malnutrition as observed in patients with tropical pancreatitis was a consequence of low calorie intake.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to all the individuals who consented to participate in this study. The help of Ms. L. Lakshmi Saraswathi, Ms. Nanita George, Ms. B. Spoorty, Ms. Meena N. Ramchandani and Ms. Abhilasha Jain in assisting in data collection and in making necessary modifications in the manuscript is gratefully acknowledged.

References

1. Barman KK, Premalatha G, Mohan V. Tropical chronic pancreatitis. Postgrad Med J. 2003;79:606–15.

2. Garg PK, Tandon RK. Survey on chronic pancreatitis in the Asia- Pacific region. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:998–1004.

3. The Copenhagen Pancreatic Study Group. An interim report from a prospective epidemiological multicentric study. Scan J Gastroenterol. 1981;16:305–12.

4. Robles-Diaz G, Vargas F, Uscanga L, Fernandez-del Castillo C. Chronic pancreatitis in Mexico city. Pancreas. 1990;5:479–83.

5. Premalatha G, Mohan V. Fibrocalculous pancreatic diabetes in infancy—two case reports. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1994;25:137– 40.

6. Hoet JJ, Tripathy BB. Consensus statement from the International workshop on Types of Diabetes Peculiar to the Tropics, 17-19 October, 1995, in Cuttack, India. Acta Diabetol. 1996;33:62–4.

7. Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med. 1998;78:539–53.

8. Balakrishnan V. Chronic calcific pancreatitis in the tropics. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1984;3:65–7.

9. Etemad B, Whitcomb DC. Chronic pancreatitis: diagnosis, classification, and new genetic developments. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:682–707.

10. Geevarghese PJ. Pancreatic diabetes. Bombay: Popular Prakashan; 1968. p.110–5.

11. Shaper AG. Aetiology of chronic pancreatic fibrosis with calcification seen in Uganda. Br Med J. 1964;1:1607–9.

12. Shaper AG. Chronic pancreatic disease and protein malnutrition. Lancet. 1960;ii:1223–4.

13. Pitchumoni CS. Special problems of tropical pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol. 1984;13:941–59.

14. Mohan V, Mohan R, Susheela L, Snehalatha C, Bharani G, Mahajan VK, et al. Tropical pancreatic diabetes in South India: heterogeneity in clinical and biochemical profile. Diabetologia. 1985;28:229–32.

15. Geevarghese PJ. Chronic pancreatitis and Diabetes Mellitus in the Tropics. Bombay: Varghese Publishing House; 1992. p.57–60.

16. Tandon RK, Sato N, Garg PK; Consensus study group. Chronic pancreatitis: Asia-Pacific consensus report. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:508–18.

17. Balakrishnan V, Nair P, Radhakrishnan L, Narayanan VA. Tropical pancreatitis - a distinct entity, or merely a type of chronic pancreatitis? Indian J Gastroenterol. 2006;25:74–81.

18. Gopalan C, Rama Sastri BV, Balasubramanian SC. Nutritive Value of Indian Foods. 1st edn. National Institute of Nutrition, Hyderabad: Indian Council of Medical Research; 2004. p.45–95.

19. Whitcomb DC. Inflammation and cancer V. chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;287:G315–9.

20. Chandak GR, Idris MM, Reddy DN, Bhaskar S, Sriram PV, Singh L. Mutations in the pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor gene (PSTI/ SPINK1) rather than the cationic trypsinogen gene (PRSS1) are significantly associated with tropical calcific pancreatitis. J Med Genet. 2002;39:347–51.

21. Singh S, Midha S, Singh N, Joshi YK, Garg PK. Dietary counseling versus dietary supplements for malnutrition in chronic pancreatitis: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:353–9.

22. Schultz AC, Moore PB, Geevarghese PJ, Pitchumoni CS. X-ray diffraction studies of pancreatic calculi associated with nutritional pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1986;31:476–80.

23. Midha S, Singh N, Sachdev V, Tandon RK, Joshi YK, Garg PK. Cause and effect relationship of malnutrition with idiopathic chronic pancreatitis: prospective case-control study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1378–83.