48uep6bbphidvals|336

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Fecal incontinence (FI) is a common problem with estimated prevalence ranging from 0.4 to 18 percent of adult community subjects in developed countries.[1] Fecal incontinence profoundly reduces patient’s quality of life with significant psychosocial implications.[2] It is more prevalent and severe in older people with reported frequency as high as 50% among elderly residents of nursing homes in the West.[3]

Fecal incontinence is not caused by a combination of multiple abnormalities in most patients such as defects in internal, external anal sphincters and rectal sensory abnormalities.[4] Ano-rectal manometry (ARM) along with imaging studies provides morphological and physiological assessment of the internal and external anal sphincters, rectal sensory function, compliance, and recto-anal reflexes. Detailed pathophysiological information on mechanisms of FI may help guide further treatment of these patients.[5] Defects in the external or the internal sphincters can be differentiated by ARM. Resting anal sphincter pressure is a reflection of internal anal sphincter function and low squeeze pressure or the voluntary anal contraction abnormality is noted when the external anal sphincter is defective.[6,7] ARM with biofeedback training improves objective and subjective parameters of ano-rectal function in patients with FI.[8] There is no study, however, on spectrum of ano-rectal sphincter function in patients with FI in India. We therefore, retrospectively analyzed the spectrum of abnormalities on ARM in patients with FI in a tertiary referral center in northern India.

Methods

Data from 140 patients with FI referred for ARM to the Gastrointestinal Pathophysiology and Motility Laboratory of the Department of Gastroenterology in a tertiary care center during eight-year period (June 2001 to June 2009) were analyzed in this study retrospectively. The authors affirm that all research related to this study was carried out in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration as revised in 1989.

Each patient underwent ARM after informed consent using a water perfusion manometry system (RedTech, Calabasas, Los Angeles, USA) using a standard technique. Two eight-lumen manometry catheters, one with radial ports placed 0.5 cm apart with a balloon at its tip to test for recto-anal inhibitory reflex (RAIR) and the other with all 8 ports placed circumferentially were used. The manometry catheter with circumferential ports was inserted deep inside the rectum with the patient in the left lateral position. The catheter was subsequently pulled 1 cm at a time (station pull-through, SPT) till the high pressure zone of the sphincter was reached and then, it was pulled 0.5 cm at a time till it came out of the high pressure zone. SPT was repeated twice. The length of the sphincter zone and resting sphincter pressure were estimated from an average of length and pressure data obtained from the SPT done twice. For measuring the squeeze sphincter pressure, the manometry catheter was pushed back into the rectum, sphincter was again localized using SPT, the patient was asked to squeeze the anal sphincter, and the catheter was pulled rapidly at a constant rate (rapid pull-through, RPT). This was repeated twice and an average of the values obtained on two recordings was used to measure the squeeze sphincter pressure. After removing the catheter with circumferential ports, the catheter with radial ports with balloon was inserted deep inside the rectum; 2–3 ports were positioned in the high pressure zone of the sphincter using the SPT technique. Subsequently, the balloon, which had been positioned inside the rectum, was inflated with an incremental volume of air (20 ml, 40 ml, 60 ml and so on) and deflated after inflation each time. During the inflation, RAIR was observed, the rectal sensations and maximum tolerable volume (feeling of distension, urge to pass stool and pain) were also assessed.

Criteria: The ARM signal was analyzed using GIPC software from RedTech. The data so obtained were interpreted based on the standard criteria described previously. [9,10,11] A resting pressure <40 mmHg, squeeze pressure < 60mmHg, length of anal high pressure zone <2.5 cm in females and <3 cm in males were considered as abnormal. Maximum tolerable volume <200ml on intra-rectal balloon distension was considered as abnormal.[9,10,11]

Statistical analysis: The data were checked for distribution using Shapiro-Wilk test. Parametric continuous data were expressed as mean and standard deviation. Non-parametric continuous data were expressed as median and inter-quartile range. Parametric and non-parametric continuous unpaired data were analyzed by unpaired t test and Wilcoxon ranksum test, respectively. Categorical data were analyzed by Chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test as applicable. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

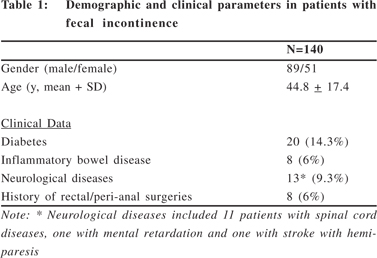

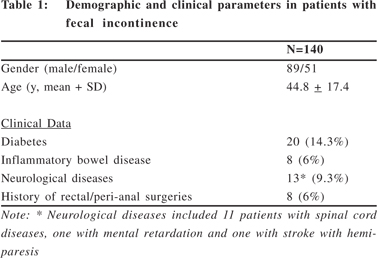

Demographic Parameters: Demographic and clinical parameters are shown in Table 1. All the patients had clinically significant FI.

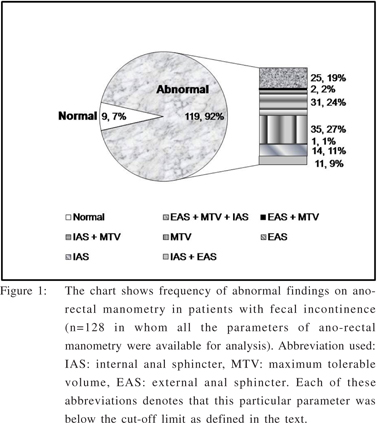

ARM parameters: Most patients with abnormal ARM parameter had multiple abnormalities (Figure 1). The internal sphincter defect as evidenced by low resting pressure (<40mmHg) was noted in 88/140 (63%) with median pressure of 34 mmHg (range 7 to 133 mmHg). External sphincter defect as evidenced by low squeeze pressure (<60mmHg) was found in 44/140 (31.4%) with median squeeze pressure of 76.5-mmHg (range 14 to 312 mmHg). Table 2 shows ARM parameters of female patients as compared to those of males. Female patients more often had low squeeze pressure suggesting external sphincter defect though other ARM parameters were comparable among the two genders.

Of 128/140 patients in whom data on tolerability to intrarectal balloon distension was available, 93 (72.7%) had low maximum tolerable volume (abnormal < 200 ml). Median value of maximum tolerable volume was 140 ml (range 40 to 300 ml). The maximum tolerable volume among female and male patients was comparable (Table 2).

RAIR data was available in 108/140 patients. Most patients 87/108 (80.5%) had normal RAIR. 18/108 (16.6%, 12 males) patients had too low basal sphincter pressure to appreciate RAIR. Incomplete RAIR was observed in 3/108 patients (all diabetic).

Anal high pressure zone was short (<2.5 cm in females and <3 cm in males) in 47/149 (33.6%) patients. The frequency of finding a short anal high pressure zone was comparable among females and male s[15/51 (29.4%) vs. 34/89 (38.2%), p =ns).

Discussion

In the current retrospective analysis, we found that parameters of ano-rectal functions were abnormal in varying combination on ARM in a large proportion of patients with FI attending a tertiary care center and female patients more often had external sphincter defect than male patients though anal resting pressure, length of the high pressure zone and tolerability to intra-rectal balloon distension were comparable.

Maintenance of continence involves the proper functioning of the sphincters, the rectal sensation and compliance and the rectoanal angle. The internal anal sphincter contributes approximately 70% to 85% of the resting sphincter pressure and is chiefly responsible for maintaining anal continence at rest.[12,13] The external anal sphincter is under voluntary control through the pudendal nerve and squeeze pressure on ARM is the reflection of external anal sphincter function.

In our study, the majority of patients had a combination of defects as previously described by others.[4] A large proportion of patients (35/128) had abnormally low maximum tolerable volume on intra-rectal balloon distension with normal sphincter pressures highlighting the importance of rectal compliance and sensitivity in maintenance of continence. Our result, however, was contradictory to two studies from Sun et al and Holmberg et al who found that all the patients with reduced tolerance to intra-rectal balloon distension had low sphincter pressure.[4,14] FI in patients without anal sphincter weakness might result from, (1) failure to maintain anal pressure during rectal distension, and (2) a blunted sensation or lack of adaptation of the bowel wall to rectal filling. Siproudhis et al in a series of patients with normal anal sphincter pressure suggested a reduced rectal adaptation could be involved in fecal leakage in patients without anal sphincter weakness.[15]

In our study, a defective external anal sphincter was significantly more common in female subjects. Obstetric injury is a contributing factor for FI. Obstetric trauma tends to be either a combination of injury to both sphincters or to the external sphincter alone and more severe injury is more likely to cause FI.[16,17] In the Indian subcontinent home deliveries are common with risk of perineal injury and subsequent development of FI.[18,19] In a series by Enck et al, both internal and external sphincter pressures were lower in female subjects; however, in our study population external sphincter defect was more common in female subjects.[20] This difference might be attributed to the obstetric practices in India. Since it is a retrospectively study, information on obstetric injury was not available in all the female patients. A prospective study is needed on this issue.

In conclusion, we found that FI in most patients is of multifactorial etiology with varying combinations of internal, external sphincter or rectal compliance defects. External sphincter defect was more common in females as compared to males.

References

1. Macmillan AK, Merrie AE, Marshall RJ, Parry BR. The prevalence of fecal incontinence in community-dwelling adults: a systematic review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1341–9.

2. Bharucha AE, Zinsmeister AR, Locke GR, Schleck C, McKeon K, Melton LJ. Symptoms and quality of life in community women with fecal incontinence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1004–9.

3. Wald A. Faecal incontinence in the elderly : epidemiology and management. Drugs Aging. 2005;22:131–9.

4. Sun WM, Donnelly TC, Read NW. Utility of a combined test of anorectal manometry, electromyography, and sensation in determining the mechanism of ‘idiopathic’ faecal incontinence. Gut. 1992;33:807–13.

5. Kumar A, Rao SS. Diagnostic testing in fecal incontinence. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2003;5:406–13.

6. Barthet M, Bellon P, Abou E, Portier F, Berdah S, Lesavre N, et al. Anal endosonography for assessment of anal incontinence with a linear probe: relationships with clinical and manometric features. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2002;17:123–8.

7. Azpiroz F, Enck P, Whitehead WE. Anorectal functional testing: review of collective experience. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:232–40.

8. Rao SS, Welcher KD, Happel J. Can biofeedback therapy improve anorectal function in fecal incontinence? Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:2360–6.

9. Felt-Bersma RJ, Klinkenberg-Knol EC, Meuwissen SG. Anorectal function investigations in incontinent and continent patients. Differences and discriminatory value. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33:479–85; discussion 485–6.

10. Jorge JM, SD Wexner. Anorectal manometry: techniques and clinical applications. South Med J. 1993;86:924–31.

11. Jorge JMN, Waxner SD. A practical guide to basic anorectal physiology investigations. Contemp Surg. 1993;4:214–24.

12. Frenckner B, Euler CV. Influence of pudendal block on the function of the anal sphincters. Gut. 1975;16:482–9.

13. Rao SS. Pathophysiology of adult fecal incontinence. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(Suppl 1): S14–22.

14. Holmberg A, Graf W, Osterberg A, Påhlman L. Anorectal manovolumetry in the diagnosis of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:502–8.

15. Siproudhis L, Bellissant E, Pagenault M, Mendler MH, Allain H, Bretagne JF, et al. Fecal incontinence with normal anal canal pressures: where is the pitfall? Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1556–63.

16. Damon H, Henry L, Barth X, Mion F. Fecal incontinence in females with a past history of vaginal delivery: significance of anal sphincter defects detected by ultrasound. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1445–50; discussion 1450–1.

17. Fenner DE, Genberg B, Brahma P, Marek L, DeLancey JO. Fecal and urinary incontinence after vaginal delivery with anal sphincter disruption in an obstetrics unit in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:1543–9; discussion 1549–50.

18. Thind A, Mohani A, Banerjee K, Hagigi F. Where to deliver? Analysis of choice of delivery location from a national survey in India. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:29.

19. Tuladhar H, Dali SM, Pradhanang V. Complications of home delivery: a retrospective analysis. J Nep Med Assoc. 2005;44:87-91.

20. Enck P, Kuhlbusch R, Lübke H, Frieling T, Erckenbrecht JF. Age and sex and anorectal manometry in incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:1026–30.