The capping protein regulator and myosin 1 linker 2 (CARMIL2) deficiency is an autosomal recessive combined immunodeficiency that leads to combined T-cell, B-cell, and NK cell defects. Matsuzaka et al showed downregulated expression of CARMIL2 gene in epithelial cells of patients with psoriasis vulgaris1. The CARMIL2 protein is expressed in the skin, lymphoid tissue, and gastrointestinal system. To date, less than 50 cases of CARMIL2 mutations have been reported worldwide. CARMIL2 mutation presents with a varying spectrum of symptoms, including cutaneous and respiratory allergies characterized by eczematous lesions, early-onset inflammatory bowel disease (EO-IBD), recurrent bacterial, fungal, and viral infections (mucocutaneous candidiasis, skin abscesses, mycobacterial infections), Epstein Barr Virus-related smooth muscle tumors and growth retardation. Immunological defects include defective T regulatory and cytotoxic cell function2,3.

Case Report

A 5-year-old boy, born out of a 3rd degree consanguinity presented with recurrent episodes of respiratory tract infection and oral thrush (responded to topical antifungals) from 6 months of age. He also had eczematous skin lesions, cheilitis, scaly with crusting lesion of lips and anterior nares since 1 year of age, and a persistent digital wart since 2 years of age. At the age of 2, he also had an episode of presumptive pulmonary tuberculosis, which responded to anti-tubercular therapy (presented with low-grade fever and chronic cough; chest x-ray and HRCT thorax showed persistent consolidation). There was history of the elder sibling’s death due to recurrent pneumonia at 8 months of age.

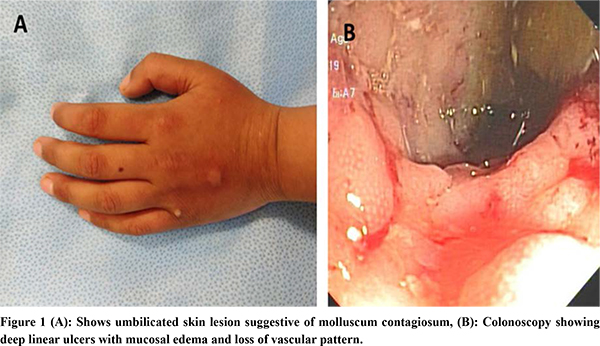

At the time of presentation, the child had chronic large and small bowel-type of diarrhea with significant failure to thrive. On examination, his weight was at -1.75 Z (normal) and height at -2.6 Z (severe stunting), and he had severe pallor, multiple erythematous lesions in peri-orifical regions, a few warts over trunk and fingers, and absent BCG scar. Systemic examination was normal.

Due to the history of recurrent infections, colitis and clinical features suggestive of a T-cell defect, such as oral thrush, molluscum contagiosum, and an absent BCG scar, further workup was done.

Human immunodeficiency virus test result was non-reactive. Immunophenotype markers included T-cell markers: CD3+: 78.6% (62-87), CD3+ CD4+: 14.9% (32-64), CD3+CD8+: 67.8% (15-46), CD4+CD8+: 0.2 (0.69-4.2), B-cell markers: CD19+: 6.1% (6-23) and CD20+: 6.2% (6-23) and NK cell markers: CD3-CD56+: 4.49% (control 4.07%), CD3-CD16+:18.2% (control 5.13%), CD3+CD56+CD16+: 21.8 % (control 4-26%), NK CD3-CD56+ perforin: 94.3% (>90). The CD4+: CD8+ ratio was below the normal range. Immunoglobulin profile revealed serum IgA: 147 mg/dL, IgG: 634mg/dL, IgM: 192 mg/dL, all of which were normal for the age. CT enteroclysis showed diffuse asymmetric enhancing wall thickening involving the entire colon. Upper endoscopy revealed linear erosions in the distal esophagus. Colonoscopy showed pancolitis with discrete areas of linear serpiginous ulcer with skip lesion as shown in Figure 1. Histopathology revealed chronic active colitis and no granuloma. Colonic biopsies for CMV immunohistochemistry showed no inclusion bodies, tubercular culture, stool for Clostridium difficile toxin and opportunistic infections were unyielding.

The child was started on azathioprine and 5-aminosalicyclic acid. After 4 months of therapy, his hemoglobin improved to 12.3g/dL, and albumin was 3.7g/dL. Whole exome sequencing performed to consider the possibilities of monogenic inflammatory bowel disease/ primary immunodeficiency, revealed homozygous mutation in CARMIL2 c.1528 C>T (p.Gln510Ter), which is autosomal recessively inherited. Currently, he has been in clinical remission for the past six months and is being evaluated for allogeneic bone marrow transplant as a definitive therapy.

Discussion

IBD is a complex multifactorial disorder with varying pathogenesis, including immunodeficiency and autoimmune-related factors. Among the very early onset IBD cases, monogenic variants related to primary immunodeficiency constitute approximately 15-20% of the VEO-IBD cases4. Recurrent opportunistic infections, dermatitis and autoimmunity is associated with a monogenic variant of VEO-IBD. Diagnosing monogenic VEO-IBD requires detailed history of resent illness and family history, clinical examination, evaluation of B-cell and T-cell assays. Next-generation sequencing can aid in the diagnosis. It is essential to do genetic analysis especially when there is high suspicion for monogenic variant of VEO-IBD, as these cases are usually refractory to conventional immunomodulatory therapy and require specific targeted therapy like hematopoietic stem cell transplant for cases such as those resulting from interleukin-10 deficiency.

CARMIL2 deficiency, has recently been described as a cause of autosomal recessive combined immunodeficiency disorder causing both T-cell and B-cell dysfunction. In our case, we have shown that CARMIL2 deficiency can present with IBD-like symptoms and has shown a good response to conventional immunosuppressive therapy. Although certain case reports suggest that CARMIL2-related IBD may be refractory to conventional immunotherapy and TNF-a inhibitors, this could be due to genotype-phenotype variations in disease severity.

In our index case, a homozygous novel mutation was detected c.1528C>T (p.Gln510Ter) in CARMIL2 gene. This variant is likely pathogenic (PVS1, PM2, PP3) according to the ACMG criteria5. This variant is predicted to cause loss of normal protein function through protein truncation and is also conserved across species. In silico analysis indicates that the effect of variant is damaging. The variant detected on exome sequencing was also verified by Sanger sequencing. Targeted Sanger sequencing in the younger sibling showed her to be homozygous for the wild variant. The CCDS sequence used for CARMIL2 is NM_001013838.3. HLA typing is planned so that the sibling can act as a donor for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation6.

Our case highlights both intestinal and extraintestinal manifestation of CARMIL2-deficiency, suggesting the role of immune regulation in intestinal homeostasis. This provides another critical example where PID can present with phenotypic characteristics of early onset-IBD and should be considered in differential diagnosis. Early diagnosis of CARMIL2 deficiency in VEO-IBD patients is critical to prevent fatal complications. We hope that our case enhances the recognition of the clinical manifestations of this recently recognized immunodeficiency and adds to the differential diagnosis of IBD in the pediatric population, especially if there are clinical signs and symptoms suggestive of T -cell deficiency/defects.

Conclusion

In conclusion, a detailed history and examination of extraintestinal manifestation can provide valuable clues, and genetic diagnosis is essential in cases of VEO-IBD to confirm the etiology. Though immunosuppressive therapy in CARMIL deficiency is helpful to tide over the crisis, a definitive hematopoietic stem cell transplant offers a gratifying response in the long term.

References

- Matsuzaka Y, Okamoto K, Mabuchi T, Iizuka M, Ozawa A, Oka A, et al. Identification, expression analysis and polymorphism of a novel RLTPR gene encoding a RGD motif, tropomodulin domain and proline/leucine-rich regions. Gene. 2004;343(2):291–304.

- Alazami AM, Al-Helale M, Alhissi S, Al-Saud B, Alajlan H, Monies D, et al. Novel CARMIL2 Mutations in Patients with Variable Clinical Dermatitis, Infections, and Combined Immunodeficiency. Front Immunol. 2018;9:203.

- Sorte HS, Osnes LT, Fevang B, Aukrust P, Erichsen HC, Backe PH, et al. A potential founder variant in CARMIL2/RLTPR in three Norwegian families with warts, molluscum contagiosum, and T-cell dysfunction. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2016;4(6):604–16.

- Kelsen JR, Russo P, Sullivan KE. Early-Onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2019;39(1):63.

- Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med 2015;17(5):405–24.

- Rastogi N, Thakkar D, Yadav SP. Successful Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant for CARMIL2 Deficiency. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2021;43(8):e1270–1.