48uep6bbphidcol2|ID

48uep6bbphidvals|3037

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Introduction

Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is a standard procedure for peri-ampullary tumours. It’s a circuitous procedure involving retroperitoneal dissection around frangible structures. Even though laparoscopic Whipple’s pancreaticoduodenectomy (WPD) was described two decades back by Gagner et al.1 and there has been literature supporting the same2,3 it has not become as popular perhaps because surgeons all over the world have been wary about the laparoscopic approach mainly because of difficult dissection and requirement of three anastomoses. The most difficult anastomosis among these is the pancreato-jejunostomy which is rightly considered the Achilles heel of the procedure in view of significant leak rate and the associated high morbidity. We have adopted a modified laparoscopic pancreatic stump drainage with pancreato-gastrostomy, involving pancreatic stump mobilization with its invagination into the lumen of the stomach via posterior gastrotomy and fixation with two ‘U’ shaped sutures to the posterior wall of the stomach, traversing across the pancreatic parenchyma.

Materials and Methods

We did a retrospective analysis of a prospectively maintained database of patients who underwent laparoscopic WPD from November 2017 to March 2019 in the Department of GI Surgery, GB Pant Institute, New Delhi. Our initial endeavour in laparoscopic WPD started with laparoscopic resection with assisted anastomoses. After the experience with lap assisted WPD, we embarked on a total laparoscopic WPD.

Work-up and operative procedure

All patients underwent triphasic contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the abdomen (CECT scan) for pre-operative staging. Preoperative biliary drainage was done in patients either with serum bilirubin levels exceeding 15mg% or if there was evidence of cholangitis. All patients underwent laparoscopic WPD and pancreatic drainage by pancreatico-gastrostomy (P-G). The extent of lymph node dissection included removal of pancreaticoduodenal, pericholedochal, periportal, along with hepatic artery and lymph nodes to the right of coeliac and superior mesenteric artery. All surgeries were performed under the direct supervision of two senior surgeons (AKA, AJ). Resection margins in the specimen at the level of the bile duct, pancreatic duct, superior mesenteric artery and superior mesenteric vein were inked/marked before sending for histopathology. Resected specimens were analysed for the location, size and differentiation of the tumour, perineural invasion (pni), the status of the lymph nodal involvement and resection margins.

Follow-up protocol plan includes outpatient visits every 3 months in the 1st year, every 6 months for the next 2 years and yearly thereafter. At each follow up complete physical examination along with blood biochemistry and ultrasound abdomen were performed. The CT scan of the abdomen was performed at 1-year and when clinically indicated. Morbidity and mortality was noted over a 90 day follow up period.

Surgical technique

After induction of general anaesthesia, a nasogastric tube and foley’s urinary catheter were inserted with proper aseptic precautions, and the patient was placed in a supine position with leg split and head-end elevated.

Pneumoperitoneum was created by inserting a veress needle inserted infraumblical or at palmer’s point or via trocar inserted two cms below the umbilicus in the midline by open technique. Six ports (A 12 mm, infraumbilical-camera port (10 mm, 300), 12 mm, left hypochondrium port-in the midclavicular line at the sub-costal margin, 5 mm left iliac fossa port in the midclavicular line, 12 mm port in RIF, midclavicular line, 5 mm port in the left hypochondrium, anterior axillary line, 5 mm port in the epigastric region for liver retraction.

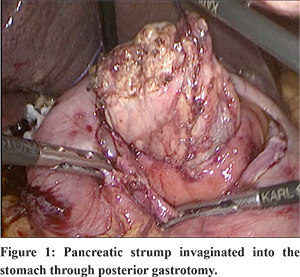

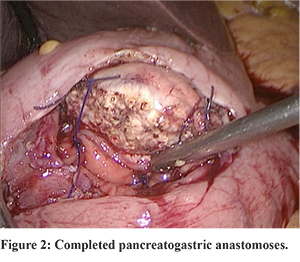

Staging laparoscopy was done in all patients to rule out metastatic disease. In case of suspected metastatic deposits, tissue was sent for frozen section analysis. After staging laparoscopy, the gastrocolic omentum was divided and lesser sac entered. The duodenum was kocherized upto the left of IVC. The hepatic artery and GDA identified and GDA test clamped, ligated and divided. The portal vein was identified at the inferior border of the pancreas; a tunnel was made with blunt and sharp dissection in the neck region of the pancreas. The CBD was looped and transected. The stomach was transected just proximal to pylorus using Echelonflex endopath 60 mm blue. The inferior border of the pancreas was identified and dissected. The infra-pancreatic SMV was identified. The neck of the pancreas was divided with a harmonic scalpel. The D-J flexure was mobilised and the specimen delivered after transecting jejunum -10 cms from D-J flexure. The pancreatic stump was mobilised for a length of 3-4 cms along the splenic vein and artery for its easy invagination into the stomach lumen. An anterior gastrotomy and a posterior gastrotomy were made. Posterior gastrotomy is carefully made according to the girth of the pancreas so that it fits snugly in it. The pancreatic stump was pulled into the stomach for a length of 2-3 cms (Figure 1). PG was done by prolene 2-0 using two‘U’ shaped sutures to the posterior wall of stomach passing across the pancreas, suturing done through the wide anterior gastrotomy (Figure 2).

Using two prolene 2-0 sutures, a double-ended suture of the approximate length of 15 cms was prepared. After the pancreatic stump was invaginated into the gastric lumen for a minimum length of 2 cms, through the posterior gastrotomy, one end of the prolene stitch was passed from the mucosal aspect to the serosal aspect of the posterior gastric wall, then through the full thickness of the pancreas and then from the serosal aspect to mucosal aspect of the opposite posterior gastric wall. The same maneuver was repeated using the other end of the suture to complete the ‘U’ shaped horizontal trans fixation suture and the sutures tied. One more stitch was passed similarly at the other end of the pancreas.

After completion of the anastomosis, any minor bleeding from the pancreatic surface was checked for and dealt with accordingly. HJ was done using the end of the jejunum which was brought through retro-colic route. Antecolic GJ was done at 40 cm distal to HJ by handsewn technique. The specimen was retrieved via the intra-umbilical port after extending the incision to an approximate length of 5 cms or pfannenstiel incision. A drain was placed close to the anastomosis and brought out through the right abdominal port. Patients are managed post-operatively in a high dependency unit. Patients with the smooth immediate post-operative course were started on oral liquids on POD-3 after clamping the Ryle’s tube and it was removed on POD-4 if the patient seemed to tolerate oral feeds well. The drain was removed when the output was less than 30 ml with normal drain fluid amylase.

Results

A total of 34 patients underwent totally laparoscopic WPD during this study period. All patients underwent pancreato-gastrostomy, with a modified pancreatic stump drainage technique as described.

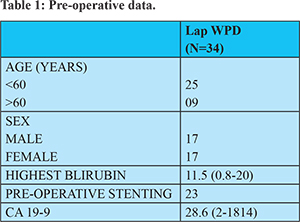

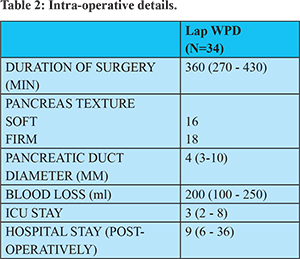

The median age was 50 years (27 to 70 years) with 17 male and 17 female patients. (Table 1) All patients had good performance status with well controlled co-morbidity if any. The median operative time was 360 mins (270- 430) with an intra-operative blood loss of 200 ml (100- 250 ml). In our initial case series time required for surgery was relatively more, but with learning curve as more cases were done, the time taken decreased. (Table 2) Of these patients, 23 patients had their tumours arising from the ampulla, 6 from the duodenum, 3 from the pancreas and 1 from the distal common bile duct. The average size of the tumour was 2.5 cms (1-4.5) Size of the tumour did not influence the difficulty of surgery untill there was surrounding structure involvement or vascular involvement. One patient had a large symptomatic microcystic serous cystadenoma of the head of the pancreas measuring 8 cms which required Whipple’s procedure. 16 patients had a firm pancreas with the remaining 18 having a soft pancreas and pancreatic duct diameter was more than 3 mm in 17 patients (median size 4 mm)

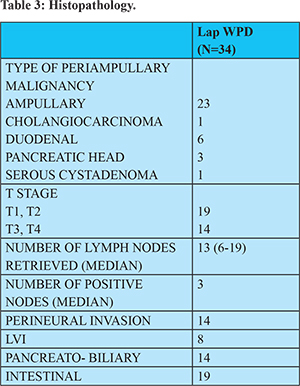

All patients had a R0 resection with a median lymph node yield of 13 (6-19). 9 patients had stage 1 disease, 10 patients had stage 2 disease and 14 patients had stage 3 disease. 31 patients had moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma with 2 patients having well-differentiated tumour morphology. 14 patients had pancreatobiliary differentiation with the remaining 19 patients having intestinal differentiation. (Table 3)

Four patients had DGE with two having grade A and two having grade B severity. Four patients had pancreatic leaks with 3 having grade A fistula, and one having grade B fistula requiring PCD drainage of the collection. Three patients had post-pancreatectomy haemorrhage with one of the patients requiring laparotomy and control of bleeding from the pancreatic stump on POD-2 (grade C). The remaining 2 patients were managed conservatively (grade A). One patient had a bile leak in the immediate post-op period which required PCD drainage. The overall number of significant complications according to Clavien-Dindo classification was 17.6% (Grade 3 and higher) [Grade 1-3, Grade 2-6, Grade 3-5, Grade 4-1, Grade 5-0](Table 4)

None of the patients developed exocrine/ endocrine insufficiency in the immediate post-op period. The median length of ICU /HDU stay was 3 days with the median hospital stay being 9 days (6-36 days)

Discussion

Laparoscopic WPD procedure with P-G offers a simple technique of pancreatic drainage that can be done relatively easily by laparoscopic technique. The potential physiological advantages of PG are: 4(1) P-G anastomosis is relatively easier in small diameter ducts and the outcome doesn’t depend on the texture of the gland and size of the duct (2) Pancreatic enzymes are inactivated by the acidic pH in the stomach (3) Only two anastomoses are done on a single jejunal loop.

P-G as an anastomotic technique for pancreatic drainage was first described by Waugh and Clagett in 19465. Since then many modifications in the technique have been described (binding and trans fixation) with comparable results. A pancreas sutureless binding technique for P-G was described by Peng SY et al. in 26 patients6. He used two purse-string sutures, one at the seromuscular level and one at the mucosal level of posterior gastrotomy to bind the pancreatic stump in the gastric lumen. He reported complications as 1 case of intra-abdominal bleed, two cases of DGE and one case of ascites all managed non-surgically. However too tight a purse-string may compromise the blood supply to the tip of the already mobilised pancreas. Ohigashi et al.7 described usage of 2-4 U shaped trans-fixation sutures for P-G with knots of the sutures placed on the serosal aspect of posterior gastrostomy with no anterior gastrotomy. Daniel kostov et al8 did a study with P-G as the pancreatic stump drainage method after open Whipple’s PD procedure in 32 patients. Their technique involved dunking of the pancreas into the stomach lumen via posterior gastrotomy with continuous seromuscular circular suture (3-0 PDS) placed around the posterior gastrotomy, 1 cm away from the cut edge. They concluded that this suture-less P-G seems to lessen the risk of a pancreatic leak, probably by diminishing the possibility of suture damage to the pancreas and by embedding the transected stump onto the posterior gastric wall. However, in this technique, no retention sutures are placed in the pancreas and continuous suture might have a purse-string effect on the pancreatic stump causing venous congestion.

We used a modified ‘U’ shaped two transfixation suture technique for P-G as already described in methods. We do the anastomosis under direct visualisation via the anterior gastrotomy. Also, adequate mobilisation of the pancreatic stump for a minimum length of 3 cms is an important step. The length of posterior gastrotomy should be in accordance with the girth of the pancreas and should be such that the pancreas fits in snugly when invaginated thus nullifying the requirement of a purse-string suture as described in some studies. Also since the pancreatic stump, after P-G is directly visualised through the anterior gastrotomy, any minor bleeding from the pancreatic surface can be visualised and accordingly managed. Pancreatic surface bleeding is the most common reason stated in most of the studies as a cause of post pancreatic haemorrhage following P-G in Whipple’s procedure. This procedure is a simplified modification of P-G that can be easily adapted for laparoscopic WPD procedure with good results.

Pancreatogastrostomy versus pancreatojejunos-tomy for reconstruction after pancreatoduodenectomy (RECOPANC) study was a multicentre RCT including 320 patients who underwent open WPD. In this study, there was no significant difference in the rate of grade B/C fistula after PG versus PJ (20% vs 22%, P = 0.617). The overall incidence of grade B/C fistula was 21%, and the in-hospital mortality was 6%. Multivariate analysis of the primary endpoint suggested soft pancreatic texture was the only independent risk factor. Compared with PJ, PG was associated with an increased rate of grade A/B bleeding events, perioperative stroke, less enzyme supplementation at 6 months, and haemorrhage (PPH) (OR: 1.52, 95%CI: 1.08-2.14). There was no difference between the two techniques in terms of clinically significant PPH (OR: 1.35, 95%CI: 0.95-1.93) and clinically significant postoperative delayed gastric emptying (DGE) (OR: 0.98, 95%CI: 0.59-1.63)

Most of the available literature on the surgical management of periampullary tumours is by an open technique with some studies reporting the outcomes following a laparoscopic WPD. Although technically challenging, the laparoscopic approach has been reported to have advantages over the open approach in terms of better intraoperative visualization (from the resultant magnification) thereby facilitating dissection, and early postoperative recovery12.

In our study, majority of the patients had ampullary tumour (67.8%) with relatively low CA 19-9 levels (median- 28.6). PADULAP14 trial and the LEOPARD 216 trial had pancreatic head malignancy type as the majority (46.9% and 28% respectively ) however the PLOT13 trial again had a higher incidence of ampullary tumours( 46.9%).

The median duration of surgery was 360 minutes with the time taken for surgery improving with standardization of steps in our study. Median operative time in PADULAP and the LEOPARD 2 trial was 486 minutes and 410 minutes. This relatively less operative time in our study could be because of the P-G anastomosis done, which is a relatively simpler anastomosis as when compared to P-J and also the majority of the tumours were ampullary with relatively easy tunnel formation along the portal vein which could be difficult in pancreatic malignancy due to desmoplastic reaction in that area.

The median duration of ICU stay in our study was 3 days and hospital stay was 9 days. Ugo boggi et al. published a systematic review and metanalysis including 25 studies and a total number of 746 laparoscopic Whipple’s procedure. The mean length of hospital stay was 13.6 days (7-23), showing geographic variability (21.9 days in Europe, 13.0 days in Asia, and 9.4 days in the US). In the PLOT trial, median hospital stay for patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery was 7 days as when compared to patients undergoing open surgery which was 13 days (p=0.001) thus validating the advantage of laparoscopic procedures in terms of early postoperative recovery, less pain and hence early discharge.

Lymph node yield is considered one of the surrogate markers for adequate dissection. In our study, the median lymph node yield was 13 which is considered adequate for periampullary tumours and is in accordance with the published data.

In our study, three patients had PPH (8.8%), one of them had an intra-luminal bleed on pod 2, which required laparotomy and suture ligation of the bleeder from the pancreatic surface (grade C haemorrhage) (since the patient was unstable, endoscopy was not attempted in the patient) The other two patients had early, intra-luminal bleed (grade A) which was managed conservatively. The cut end of the pancreas presents a raw area and because of its high vascularity, bleeding from the pancreatic surface is a well-known complication. As described in our technique, since the anastomosis is done through the anterior gastrotomy, adequate visualisation of P-G can be done for any bleeding immediately after the reconstruction.

The PLOT, PADULAP and LEOPARD 2 trials reported incidence of PPH as 9.3%, 9.3% and 10% respectively. However, in our study, only one patient had a clinically significant bleed requiring intervention. Also, two patients who had grade A, bleed had jaundice levels of more than 10 mg% when they were operated. The incidence of POPF was relatively less in our study (11.7%) when compared to other RCTs. The main reason could be because of the modified P-G technique adopted by us which provides for a snug pancreatic dunking into the stomach with adequate fixation. Also, the results did not seem to depend on the pancreas texture or the size of the duct.

However, there have been studies on laparoscopic WPD with reported increased morbidity when compared to open procedures18,19. The latest being the RCT LEOPARD 2 trial which was prematurely terminated by the data and safety monitoring board because of a difference in 90-day complication-related mortality (five [10%] of 50 patients in the laparoscopic Pancreaticoduodenectomy group vs one [2%] of 49 in the open Pancreaticoduodenectomy group; risk ratio [RR] 4.90 [95% CI 0.59-40.44]; p=0.20) This study was a multicentre trial.

However, RCTs from single centres with a good annual volume of cases (Table 5) has shown equivalent results as with open Whipple’s procedure with early functional recovery thus establishing the importance of learning curve, institutional experience and the volume of cases at a particular centre.

Conclusion

Laparoscopic WPD is a feasible procedure in the hands of ‘well-trained surgeons’ in high volume centres but has a steep learning curve. Modified P-G as described,simplifies the pancreatic drainage with a low incidence of POPF and its attendant complications.

References

- Gagner M, Pomp A. Laparoscopic pylorus¬preserving pancreatoduodenectomy. Surg Endosc 1994; 8: 408–10.

- De RooijT, LuMZ, SteenM, Gerhards MF, Dijkgraaf MG, Busch OR et al. Minimally invasive versus open pancreatoduodenectomy. Ann Surg 2016; 264: 257–267.

- Chen K, Pan Y, Liu XL, et al. Minimally invasive pancreaticoduodenectomy for periampullary disease: a comprehensive review of literature and meta-analysis of outcomes compared with open surgery. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017;17:120.

- Osman MM, Abd El Maksoud W. Evaluation of a new modification of pancreaticogastrostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy: anastomosis of the pancreatic duct to the gastric mucosa with invagination of the pancreatic remnant end into the posterior gastric wall for patients with cancer head of the pancreas and periampullary carcinoma in terms of postoperative pancreatic fistula formation. Int J Surg Oncol. 2014;2014:490386

- J. M. Waugh and O. T. Clagett, “Resection of the duodenum and head of the pancreas for carcinoma. An analysis of thirty cases,” Surgery, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 224–232, 1946

- S. Y. Peng, D. F. Hong, Y. B. Liu, J. T. Li, F. Tao, and Z. J. Tan, “A pancreas suture-less type II binding pancreaticogastrostomy,” Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi, vol. 47, no. 23, pp. 1764–1766, 2009.

- H. Ohigashi, O. Ishikawa, H. Eguchi et al., “A simple and safe anastomosis in pancreaticogastrostomy using mattress sutures,” American Journal of Surgery, vol. 196, no. 1, pp. 130–134, 2008.

- Daniel Kostov et al./ International Journal of Surgery and Medicine (2015) 1(1); 2-6

- Lyu Y, Li T, Cheng Y, Wang B, Chen L, Zhao S. Pancreaticojejunostomy Versus Pancreaticogastrostomy After Pancreaticoduodenectomy: An Up-to-date Meta-analysis of RCTs Applying the ISGPS (2016) Criteria. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2018;28(3):139–146.

- Cheng Y, Briarava M, Lai M, Wang X, Tu B, Cheng N, Gong J, Yuan Y, Pilati P, Mocellin S. Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy reconstruction for the prevention of postoperative pancreatic fistula following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017, Issue 9. Art. No.: CD012257

- Xiong JJ, Tan CL, Szatmary P et al. (2014) Meta-analysis of pancreaticogastrostomy versus pancreaticojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br J Surg 101:1196–208

- Agha, R., & Muir, G. (2003). Does laparoscopic surgery spell the end of the open surgeon? Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 96(11), 544-6.

- Palanivelu C, Senthilnathan P, Sabnis SC, et al. Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic versus open pancreatoduodenectomy for periampullary tumours. Br J Surg 2017; 104: 1443–50.

- Poves I, Burdio F, Morato O, et al. Comparison of perioperative outcomes between laparoscopic and open approach for pancreatoduodenectomy: the PADULAP randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 2018; 268: 731–39.

- Bhingare P, Wankhade S, Gupta BB, Dakhore S. A prospective randomized controlled trial comparing laparoscopic versus open Whipple’s procedure for periampullary malignancy. Int Surg J 2019;6:679-85.

- van Hilst J, de Rooij T, Bosscha K, Brinkman DJ, van Dieren S, Dijkgraaf MG, Gerhards MF, de Hingh IH, Karsten TM, Lips DJ, et al. Laparoscopic versus open pancreatoduodenectomy for pancreatic or periampullary tumours (LEOPARD-2): a multicentre, patient-blinded, randomised controlled phase 2/3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4:199–207

- Boggi, Ugo & Amorese, Gabriella & Vistoli, Fabio & Caniglia, Fabio & Lio, Nelide & Perrone, Vittorio & Barbarello, Linda & Belluomini, Mario & Signori, Stefano & Mosca, Franco. (2014). Laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy: A systematic literature review. Surgical endoscopy. 29. 10.1007/s00464-014-3670-z.

- DokmakS,Fte´richeFS,AussilhouB,BensaftaY,Le´vyP, Ruszniewski P et al. Laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy should not be routine for resection of periampullary tumors. J Am Coll Surg 2015; 220: 831–838.

- Adam MA, Choudhury K, Dinan MA, et al. Minimally invasive versus open pancreaticoduodenectomy for cancer: practice patterns and short-term out-comes among 7061 patients. Ann Surg. 2015;262:372–377.