48uep6bbphidcol2|ID

48uep6bbphidvals|2981

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Introduction

Both hepatitis B and C virus (HBV and HCV) have been recognized as major causes of acute and chronic liver disease (CLD) worldwide. There is a large degree of geographic variability in its distribution due to differences in socioeconomic status or cultural practices in different regions.1-3 The prevalence of HCV and HBV infections is not uniform throughout India.2,3

Contaminated endoscopes are a potential source of transmission of infectious agents such as Salmonella, Helicobacter pylori, Mycobacteria, and HBV and HCV virus.4-12 In a study from the USA, the transmission of infectious agents during endoscopy was estimated to be 1 in 1.8 million.13-15 The rate of transmission of HBV is low in the developed world due to the lower prevalence rate and better disinfection/sterilization protocol. Data regarding the transmission of infectious agents via gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopes are not available from low-income countries, where these infections are most prevalent. We aimed to determine the prevalence of HBV and HCV infections among patients scheduled for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (UGIE) in a teaching hospital in eastern India. We also discuss the cost-benefit of using pre-endoscopy screening tests in the endoscopic units of developing/underdeveloped countries.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted at a tertiary-care teaching hospital of Bihar, an eastern state of India. All patients provided informed consent before enrollment. The institute’s ethical review committee approved the study.

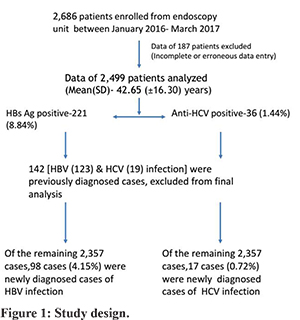

All consecutive patients attending the GI endoscopy unit for UGIE were included in the study from January 2016 to March 2017. This includes all patients scheduled for UGIE. All patients underwent screening for hepatitis B and C infection. Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and anti-hepatitis C virus antibodies (anti-HCV) were tested by immunochromatographic (ICT) assays in the laboratory. ELISA based tests were used in patients with doubtful ICT-based test results and high-risk individuals. The test result was available within 6-hours in cases of urgent endoscopy. For elective endoscopy, patients had to collect test reports before the endoscopy. Data such as age, sex, the indication of endoscopy, endoscopic diagnosis, and history regarding the risk factors for infection with HBV and HCV were collected. Data regarding the newly diagnosed patients of HBV and HCV infection and old patients of HBV and HCV infection entered. Prevalence of HBV and HCV infection in patients attending the GI endoscopy unit were calculated before and after the exclusion of already diagnosed cases of HBV and HCV-related CLD. Candidates with positive test results were counselled for the nature of infection and its further management. The study design is shown in figure-1.

Statistical Analysis

The results were analyzed with Microsoft Excel. All results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), median (range), or frequency (%) as appropriate.

Results

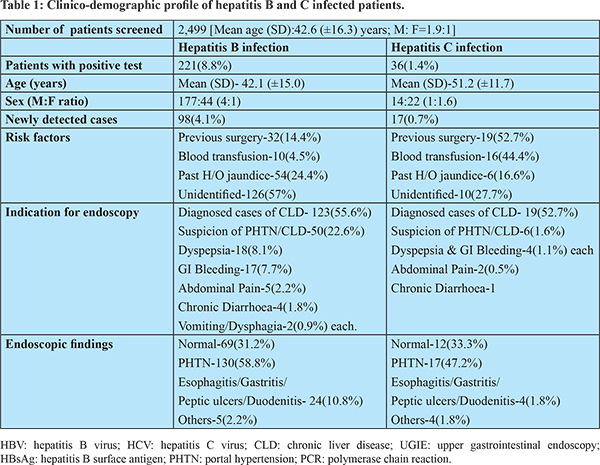

A total of 2,686 patients were screened for HBV and HCV infection from the endoscopy unit. Data of all consecutive patients who underwent UGIE were collected. Data of 187 patients were incomplete or erroneous, therefore excluded from the analysis. Of 2,686 patients, data of 2,499 patients was analysed. The mean (SD) age was 42.65(±16.3) years (M: F ratio was 1.96:1). Portal hypertension (PHTN), CLD, dyspepsia, and GI bleeding were the most common indication of endoscopy. Chronic diarrhea, recurrent vomiting, abdominal pain, ascites, dysphagia, and splenomegaly were other indications of endoscopy (Table 1).

Out of 2,499 patients, 221(8.84%) tested positive for HBsAg. The mean (SD) age was 42.13 (±15.08) years (M: F ratio 4:1). Out of 221 HBsAg positive cases, 123 (55.65%) cases were previously diagnosed cases of HBV-related CLD. Ninety-eight (44.31%) cases were newly diagnosed cases of HBV infection. History of blood transfusion and previous surgery were present in 10 (4.52%) and 32 (14.47%) patients, respectively. Past history of jaundice was present in 54 (24.43%) patients. However, risk factors of HBV-infection were not identified in the majority of patients (57%). Endoscopy findings were normal in 69 (31.22%) patients. Endoscopic evidence of PHTN was seen in 130 (58.82%) patients. Twenty-four (10.85%) patients had evidence of gastritis, peptic ulcer, esophagitis, or duodenitis. Malignancy, hiatus hernia, and vascular lesion were present in 5 (2.26%) patients. Details of patients with HBV infection are summarized in table-1.

Out of 2,499, 36 (1.44%) patients were tested positive for the anti-HCV antibody. The mean (SD) age was 51.25 (±11.78) years (M: F ratio 1:1.6). Out of 36 anti-HCV positive cases, 19 (52.77%) cases were previously diagnosed cases of HCV-related CLD. Seventeen (47.22%) cases were newly diagnosed cases of HCV infection. History of blood transfusion and previous surgery were present in 16 (44.44%) and 19 (52.77%) patients, respectively. Past history of jaundice was present in 6 (16.66%) patients. Risk factors of HCV-infection were not identified in 10 (27.77%) of patients. Endoscopy findings were normal in 12 (33.33%) patients. Endoscopic evidence of PHTN was seen in 17 (47.22%) patients. Four (1.8%) patients had evidence of gastritis, peptic ulcer, esophagitis, or duodenitis. Malignancy, hiatus hernia, and vascular lesion were present in 4 (1.8%) patients. Details of patients with HCV infection are summarized in table-1.

The overall prevalence of HBV and HCV infections in patients who underwent UGIE was 8.8% and 1.4%. Out of 2,499, 123 and 19 patients were previously diagnosed cases of HBV and HCV related CLD, respectively. The prevalence of newly diagnosed cases of HBV and HCV infection was 4.1% and 0.7%.

The frequencies of HBV infection in patients clinically diagnosed with CLD, gastrointestinal bleeding, functional bowel disorders/dyspepsia, and chronic diarrhea were 25.0%, 5.3%, 3.2%, and 3.7%, respectively. The frequencies of HCV infection in the CLD and non-CLD groups were 4.4% and 0.4%.

Discussion

In this study, the prevalence of HBV and HCV infection in patients undergoing endoscopy in a tertiary-care teaching hospital of the eastern Indian state of Bihar was 8.84% and 1.44%, respectively. After the exclusion of previously diagnosed cases of HBV and HCV-related CLD, the prevalence of newly diagnosed cases of HBV and HCV infection was 4.15% and 0.72%, respectively.

There are 400-500 million carriers of HBV worldwide, with chronic HBV at a rate of 5%.1 If we analyse most of the population-based studies from India, the prevalence of HBV infection in the general population appears to less than 3-4%.2 The estimated global prevalence of HCV infection is around 2%.3 The most systematic population-based study from the eastern Indian state of West Bengal (N=2,973) showed a seroprevalence of 0.87%.16 Data regarding the prevalence of HBV and HCV infection in the population of the eastern Indian state of Bihar is lacking. Bihar is the third most crowded state in India, with an estimated population of 108.92 million (2017). In our study, we first described the prevalence of HBV and HCV infection in patients scheduled for UGIE in this part of the country. Our study showed a higher prevalence of HBV (8.84%) and HCV (1.44%) infection in patients undergoing UGIE compared to the general populations of India.2-4

Data regarding the prevalence of HBV and HCV infection in patients undergoing endoscopy is minimal. In a study conducted in Turkey, patients visiting the gastroenterology department for endoscopy were diagnosed and, except for cirrhosis, were enrolled. Among 1,000 patients in total, 28 (2.8%) were HBsAg positive and 10 (1%) was anti-HCV positive.17 In another study by Cacabay, medical records of 2,690 participants who underwent UGIE in Ankara University were reviewed. The seroprevalence of HBV and HCV infection were 2.7% and 0.2%, respectively.18 In a recent retrospective study conducted in Nigeria, the prevalence of HBV infection was 11.5% among 772 patients who underwent UGIE.19 However, the prevalence of HBV infection recorded in the current study and the study from Nigeria is much higher than the 2.7% recorded by Cakabay and the 2.8% recorded by Gulsen et al. in Turkey. Unlike our study, patients with cirrhosis were excluded in Turkey study done by Gulsen et al. Only two studies are published from underdeveloped/developing countries regarding the prevalence of HBV and HCV infection in patients undergoing endoscopy. The current study is second only to the study from Nigeria, revealing a high prevalence of HBV infection in patients undergoing endoscopy. The study from Nigeria was retrospective in nature and consisted of a smaller sample size than the current study.19

The risk of transmission of hepatitis viruses via GI endoscopes is potentially a concern for patients and healthcare workers. In order to avoid transmitting infectious agents via endoscopy, disinfection/sterilization procedures of endoscopes and accessories are of utmost importance. Prevention of transmission of HBV and HCV infection during endoscopic procedures require strict disinfection/sterilization protocol proposed by various guidelines.13 HBV transmission is not associated with GI endoscopy when adequate endoscope reprocessing is used. However, there are a few reports of HBV transmission via GI endoscopes and accessories. In a case report, the endoscopic transmission of HBV was confirmed by molecular analysis.6 Two other reports described HBV transmission in two patients after GI endoscopy of HBV infected patients.7,8 Both patients became HBV seropositive nine months after endoscopy. The overall risk for HCV transmission through GI endoscopy is controversial. The risk for HCV transmission is extremely low when appropriate disinfection procedures are per-formed. Isolated cases of patient-to-patient transmission of HCV related to GI endoscopy were reported in the literature. HCV transmissions after GI endoscopy have been related to inadequate cleaning and disinfection of GI endoscopes and accessories9-12 and to the use of contaminated medicine vials or syringes.10,11 In two cases, genotyping and nucleotide sequencing of the viral isolates showed the same HCV strain.9-10 Suboptimal reprocessing practices such as failure to disinfect between patients, disinfection being performed only at the end of the day, inadequate disinfectants, inadequate exposure times, and improper cleaning were the reasons for patient to patient transmission of HBV and HCV infections.6-12

In the study by Gulsen et al., nearly two-third of HBV and HCV infected patients were unaware of infection at the time of diagnosis during pre-endoscopy screening.17 In the current study, nearly half of HBV and HCV infected patients were newly diagnosed as a result of our screening program. Identifiable risk factors were absent in 57% and 27.77% of HBV and HCV positive patients, respectively. Hence, just a negative history is not sufficient to rule out these infections before a GI endoscopy. Unawareness of potentially transmissible infection can be dangerous for patients and healthcare workers, especially at high volume endoscopy centres with suboptimal infrastructures.

There are a few limitations of our study. Many patients enrolled in this study were referred to our endoscopy unit for GI endoscopy, and hence follow-up of these patients was not performed. Infectivity of hepatitis virus depends upon the DNA and RNA levels, not on isolated HBsAg and anti-HCV antibody. We did not measure the DNA and RNA levels of hepatitis viruses in these patients.

The common reasons for endoscopy related infection are lack of adequate infrastructures; and the endoscope cleaning staff not strictly adhering to the recommended guidelines.20,21 Epidemiological surveys of endoscopy units have revealed that failure to comply with recommended guidelines is relatively common.22,23 Many of the endoscopy units of underdeveloped and developing counties are overburdened, understaffed, and under-equipped. Due to the scarcity of an adequate number of endoscopes and automated endoscope re-processing systems, proper disinfection/sterilization of endoscopes and accessories may be difficult and sometimes questionable.24 A study has shown that hospitals in developing countries often lack endodisinfector and the correct cleaning techniques in line with international recommendations. These endoscopic units frequently rely on pre-endoscopy screening protocol.25 The cost-benefit of getting viral serology in all patients is an important issue in low-income countries. Additional costs of dedicated endoscopes and screening tests are the major problems for routine pre-endoscopy screening. This approach is neither cost-effective nor recommended by international bodies.

It is important to note that very little research has addressed the adequacy of infrastructure and the existing practice of disinfection/sterilization procedures of endoscopes and accessories. However, the very few available studies have raised serious concern regarding the practice of disinfection/sterilization procedures in the endoscopy unit of low-income countries.24,25 It may be beneficial to include the routine pre-endoscopy screening in the endoscopy units of underdeveloped/developing countries; however, this issue needs to be debated in a rational manner with an evidence-based approach. Further study is warranted to assess the adequacy of infrastructure, risk of hepatitis virus transmission, and the cost-benefit of getting viral serology in the endoscopy units of underdeveloped and developing counties. Moreover, universal precaution to reduce the potential transmission of these infections must be strictly practiced.

Conclusion

The prevalence of HBV and HCV infection in patients undergoing endoscopy in a teaching hospital in eastern India was 8.84% and 1.44%, respectively. Pre-endoscopy screening is neither cost-effective nor recommended by international bodies. Further study is warranted to assess the adequacy of infrastructure, risk of hepatitis virus transmission, and the cost-benefit of getting viral serology in the endoscopy units of under-developed and developing counties.

References

- Lavanchy D. Worldwide epidemiology of HBV infection, disease burden, and vaccine prevention. J Clin Virol. 2005; 34 (Supp 1):1-3.

- Puri P. Tackling the Hepatitis B Disease Burden in India. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2014; 4:312-19.

- Mukhopadhyaya A. Hepatitis C in India. J Biosci. 2008; 33:465-73.

- Ishino Y, Idok K, Sugano K. Contamination with hepatitis B virus DNA in gastrointestinal endoscope channels: Risk of infection on reuse after on-site cleaning. Endoscopy 2005; 37:548-51.

- Wu H, Shen B. Health care-associated transmission of hepatitis B and C viruses in en-doscopy units. Clin Liver Dis. 2010; 14:61-68.

- Birnie GG, Quigley EM, Clements GB, Follet EA, Watkinson G. Endoscopic transmission of hepatitis B virus. Gut 1983:24:171–74.

- Morris IM, Cattle DS, Smits BJ. Letter: endoscopy and transmission of hepatitis B. Lancet 1975: ii: 1152.

- Seefeld U, Bansky G, Jager M, Schmid M. Prevention of hepatitis B virus transmission by the gastrointestinal febrescope. Successful disinfection with an aldehyde liquid. Endoscopy 1981: 13:238–39.

- Bronowicki JP, Venard V, Botté C, Monhoven N, Gastin I, Choné L, et al. Patient-to-patient transmission of hepatitis C virus during colonoscopy. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997: 337:237–40.

- Le Pogam S, Gondeau A, Bacq Y. Nosocomial transmission of hepatitis C virus. Ann. Intern. Med. 1999: 131:794.

- Muscarella LF, New York State Health Officials. Recommendations for preventing hepatitis C virus infection: analysis of a Brooklyn endoscopy clinic’s outbreak. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2001: 22:669.

- Tennenbaum R, Colardelle P, Chochon M, Maisonneuve P, Jean F, Andrieu J. Hepatitis C after retrograde cholangiography. Gastroenterol. Clin. Biol. 1993: 17:763–75.

- Petersen BT, Chennat J, Cohen J, Cotton PB, Greenwald DA, Kowalski TE, et al. Multi-society guideline on reprocessing flexible gastrointestinal endoscopes: 2011. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011; 73: 1075–84.

- Nelson DB, Muscarella LF. Current issues in endoscope reprocessing and infection control during gastrointestinal endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2006; 12:3953-64.

- Kovaleva J, Peters FT, van der Mei HC, Degener JE. Transmission of infection by flexible gastrointestinal endoscopy and bronchoscopy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013; 26:231-54.

- Chowdhury A, Santra A, Chaudhuri S, Dhali GK, Chaudhuri S, Maity SG, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection in the general population: a community-based study in West Bengal, India. Hepatology. 2003: 37: 802–9.

- Gulsen MT, Beyazit Y, Guclu M, Koklu S. Testing for hepatitis B and C virus infections before upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: Justification for dedicated endoscope and room for hepatitis patients. Hepatogastroenterology 2010; 57:797-800.

- Cakabay B, Aksel B, Sulaimanov M, Ünal E, Bayar S, Kocaoglu H, et al. Is pre-endoscopy hepatitis B and C testing useful? Ankara Univ Tip Fakultesi Mecmuasi 2011; 64:137-39.

- Akere A, Otegbayo JA, Ola SO. How relevant is pre-gastrointestinal endoscopy screening for HBV and HIV infections?. J Med Trop 2015; 17:1-3.

- Waye JD. Endoscope disinfection: The attitude of the directors of twenty gastrointestinal endoscopy training programs concerning instrument disinfection. Endoscopy Rev 1989; 6: 62-69.

- Spach DH, Silverstein FE, Stamm WE. Transmission of infection by gastrointestinal endoscopy and bronchoscopy. Ann Intern Med 1993; 118: 117-28

- Kaczmarek RG, Moore RM Jr, McCrohan J. Multistate investigation of the actual disinfection/sterilization of endoscopes in health care facilities. Am J Med 1992; 92: 257-61.

- Collignon P, Graham E. How well are endoscopes cleaned and disinfected between patients? Med J Aust 1989; 151: 269-72.

- Loots E, Clarke DL, Newton K, Mulder CJ. Endoscopy services in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa, are insufficient for the burden of disease: Is patient care compromised? S Afr Med J 2017; 107:1022-¬25.

- Mehr MT, Uddin S, Iman NU. Is universal screening of individuals for HBV, HCV and HIV before endoscopy justified? An audit of the current practices. J. Med. Sci. (Peshawar, Print) 2015; 23: 100-104.