48uep6bbphidcol2|ID

48uep6bbphidvals|1895

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Enterolithiasis, i.e. presence of stones within the intestinal tract, is a rare entity. Enteroliths could be primary (formed within the intestine) or secondary (such as gallstones and urinary stones, formed outside and migrating into intestinal tract through a fistula). Primary stones may be true (formed by precipitation of contents of chyme) or false (formed from insoluble foreign substances, such as bezoars).1 True primary enteroliths are usually associated with conditions leading to stasis such as strictures/stenosis (due to tuberculosis, Crohn’s disease, radiation, malignancy etc.), diverticula, post-operative stasis (roux loops, Billroth II gastrojejunostomy, blind pouches etc.) and medications (Calcium, diltiazem, levodopa, ursodeoxycholic acid ).1 Rare cases may arise in absence of known predisposing factors. We propose a new category, i.e. “Idiopathic true primary enteroliths”, for cases where cause remains obscure despite complete evaluation. Extensive search revealed only few such cases in medical literature. Moreover, idiopathic enterolith causing bowel perforation is even rarer, with only three reports worldwide.2,3,4 We describe an idiopathic true primary enterolith resulting in ileal perforation in otherwise normal gut. Also, a brief review of previously reported idiopathic enteroliths has been discussed.

Case Report

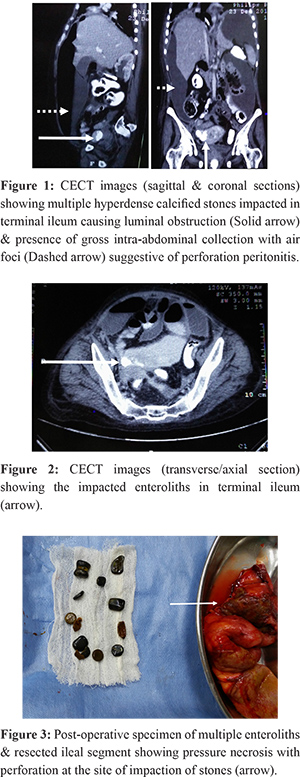

A 40 years old female presented with diffuse pain abdomen, vomiting, obstipation and abdominal distension since seven days. On examination, she had abdominal distention with diffuse tenderness, however, frank signs of peritonitis were absent. X-rays revealed dilated jejuno-ileal loops and multiple air-fluid levels but no pneumoperitoneum. Ultrasound showed free fluid with internal echoes and dilated bowel loops. No gallstones were identified. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) revealed gross intra-abdominal collection with air foci. Multiple conglomerated radiopaque stones were noted in terminal ileum with proximal dilatation (Figure 1-2). Also, extensive calcified mesenteric and retroperitoneal lymph-nodes were noted. There was no evidence of any diverticula or stricture. Gallbladder & bile duct were normal without any calculus, pneumobilia or fistula. After initial resuscitation, exploratory laparotomy was performed. Intra-operatively, there was extensive feco-purulent contamination. A perforation was noted in distal ileum three feet proximal to ileo-caecal junction with a stone protruding through the perforation. Palpation revealed multiple impacted stones causing obstruction and pressure necrosis at site of impaction. Perforated ileal segment was resected with all palpable enteroliths (Figure 3) and an ileostomy was made. Remaining small & large bowel, gallbladder & bile duct were normal. Post-operative course was uneventful except for surgical-site infection. Histopathology revealed non-specific inflammation, muscular hypertrophy and foreign-body giant cell reaction at site of impaction. There was no evidence of tuberculosis, Crohn’s disease or any specific bowel pathology. Biochemical analysis of stones revealed a combination of calcium oxalate, bile salts and bile pigments. Metabolic workup (including serum calcium & vitamin-D) was normal. Proximal and distal contrast studies, performed prior to stoma closure, revealed no abnormality. Patient underwent ileostomy closure 6 weeks after primary surgery.

Discussion

Idiopathic enteroliths appear to be commoner in India, mostly occurring in 6-7th decades without gender bias. The pathogenesis remains unknown. Possible explanations include a systemic predisposition to stone formation, intestinal dysmotility2,4 or a highly patent ileo-caecal valve.1 Post-operative adhesions could be another explanation as we noted many idiopathic cases having history of abdominal surgeries. Our patient had calcified retroperitoneal lymph-nodes which could denote sequelae of healed infections or a genetic predisposition to calcification. Increased incidence in Indians suggests dietary, geographical or genetic factors.4 Further studies are needed in this regard.

Small enteroliths are usually asymptomatic and pass spontaneously.1 We found that most cases of idiopathic enteroliths present with acute/subacute intestinal obstruction (classical “Tumbling obstruction”)1 and rarely with perforation. Only three cases of perforation secondary to idiopathic enteroliths have been reported.2,3,4 Rare complications include anaemia, haemorrhage etc.1

CECT is the investigation of choice, as X-ray detects only one-third cases.1 Although most idiopathic enteroliths were composed of calcium salts, yet they were likely to be missed on X-rays.4 Although it has been seen that even CECT can have false-negative findings.3

Treatment involves either milking the stones distally4 or, more often, enterotomy and stone retrieval.1,2-5 Rarely, hemicolectomy is required if differentiation from malignancy is not possible.3 Spontaneous passage occurs with enteroliths <2cm; however, it is unlikely with larger stones.1 Literature review suggests that multiple enteroliths near ileo-caecal junction or solitary large enteroliths in terminal ileum have high chances of obstruction/perforation and hence, should be treated promptly. Stone analysis revealed that most idiopathic stones are solitary, >2.5 cm, located in terminal ileum and composed of calcium salts predominantly.

Only after a thorough intra-operative and post-operative evaluation excludes an underlying cause, should an enterolith be labelled as idiopathic. Final confirmation is based on histopathology ruling out a bowel pathology. Prognosis is excellent in majority of cases and hence, early diagnosis and treatment is crucial. In view of possibility of recurrence, idiopathic cases must be followed-up post-operatively.1

The younger age of our patient, absence of surgical history, presentation as perforation peritonitis & presence of multiple stones make it an extremely unusual, rare & interesting case.

References

- Gurvits GE, Lan G. Enterolithiasis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(47):17819-29.

- Salim AS. Small bowel obstruction with multiple perforations due to enterolith (bezoar) formed without gastrointestinal pathology. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 1990;66(780):872-873.

- Shetty K, Sridhar A. An Unusual Presentation of Enterolithiasis. Journal of Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases. 2011;20(4):348

- Singhal BM, Kaval S, Kumar P, Singh CP. Enterolithiasis: An unusual cause of small intestinal obstruction. Archives of International Surgery. 2013;3(2):137-41.

- Quazi MR, Mukhopadhyay M, Mallick NR, Khan D, Biswas N, Mondal MR. Enterolith Containing Uric Acid: An Unusual Cause Of Intestinal Obstruction. The Indian Journal of Surgery. 2011;73(4):295-297.