48uep6bbphidcol2|ID

48uep6bbphidvals|1891

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

The term visceral larva migrans (VLM) is used to describe the migration of second-stage larvae of certain nematodes through the human viscera.1 These nematodes pass through the intestinal wall and travel with the blood stream to various organs where they cause inflammation and damage. Affected organs can include the liver, lung, heart and the central nervous system. The larvae are known to move slowly through the affected organs (hence the term migrans), the resulting inflammationcausing multiple oval to cigar-shaped eosinophilic granulomas or abscesses.2 This entity should be considered in the differential in patients with sustained eosinophilia showing the typical imaging findings. We further report secondary complications of portal vein thrombosis and abscess rupture in these patients which has so far not been documented in literature.

Case 1

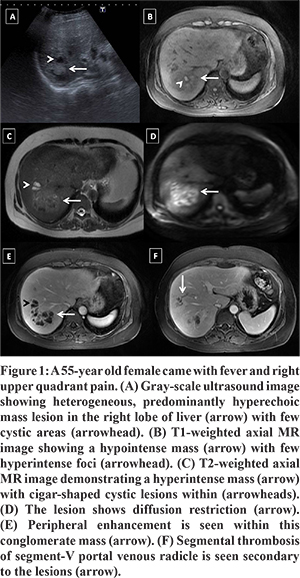

A 55-year old female came with the chief complaints of intermittent high grade fever and pain in right upper quadrant since 1 month. Her complete blood count revealed normal white blood count (9400/µL, normal range 4-11) with eosinophilia (18%). Ultrasound showed the presence of multiple conglomerated predominantly hyperechoic lesions in right lobe of liver (Figure 1A). Further, MRI (Figure 1B - F) was done which revealed multiple diffusion restricting lesions in right lobe of liver characteristically distributed along portal radicles. These were predominantly T1 hypointense and T2 hyperintense, however, some of them also demonstrated T1 hyperintensity with corresponding hypointense T2 signal. Peripheral enhancement on portal venous phase after administration of hepatobiliary specific contrast agent (Gd-BOPTA, Multihance, Bracco Diagnostics Inc.) was observed. Additionally, complete thrombosis was noted in adjacent segment V branch of right portal vein. A diagnosis of eosinophilic abscesses with adjoining segmental portal vein thrombosis was suggested on the basis of distribution of the lesions and eosinophilia. Fine needle aspiration showed cellular smears containing large number of inflammatory cells with Charcot-Leyden crystals consistent with VLM (Figure 2).

Case 2

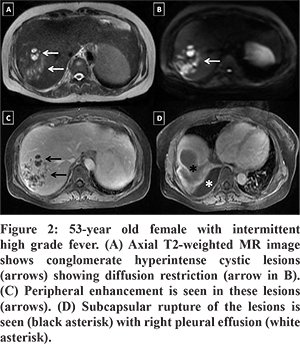

A 53- year old female presented with intermittent fever with chills since 20 days. Her routine blood tests were unremarkable except for eosinophilia (14%). Preliminary ultrasound revealed multiple confluent hypoechoic lesions consistent with features of abscesses in right lobe of liver with perihepatic fluid collection along the dome of liver. Contrast MRI (Figure 3) demonstrated multiple confluent loculated peripherally enhancing lesions along portal tracts in right lobe of liver. Also, capsular breach with T1 hypo/T2 hyperintense subphrenic collection and mild right sided pleural effusion were noted. A possibility of VLM with a differential diagnosis of amoebic abscess with contained rupture and reactionary right pleural effusion was suggested. Serological investigation (with ELISA) for Entamoeba (IgG) was negative while that for toxocaracanis (IgG antitoxocaracanis) came positive and a confimatory diagnosis was made on fine needle aspiration cytology.

Case 3

A 31-year old male presented with complaints of upper abdominal pain, off and on fever and loss of appetite for 1 month. Laboratory investigations revealed raised white blood cell count (14000/µL, normal range- 4-11) with marked eosinophilia (58%). Ultrasound revealed multiple, relatively well-defined, discrete as well as coalescing heteroechoic lesions involving the liver. Contrast-enhanced computed tomographic scan (CECT) demonstrated multiple fluid-attenuating round to oval conglomerate lesions involving the right liver lobe (Figure 4A and B) for which imaging differentials of eosinophilic or amoebic abscess were suggested. Fine needle aspiration confirmed the diagnosis and subsequent serological investigations (with ELISA) for toxocaracanis (IgG antitoxocaracanis) came positive. He was treated with albendazole leading to a significant regression in the size of the lesions (Figure 4C and D).

Discussion

Toxocaraspecies, the ascarid of dogs and cats, is the most common culprit causing VLM in humans.1 Infection can be acquired by ingesting food material contaminated by eggs of Toxocara and primarily occurs in children aged 1-4 years, but can occur at any age. The larvae hatch in the small intestine, invade the mucosa, and enter the portal system. The liver traps some larvae, but other larvae proceed to the lungs and the circulatory system, where they can disseminate to virtually every organ. In particular, the larvae deposit in the liver, lungs, eye, heart, and brain.2-5 However, the parasite cannot complete its life cycle in humans. Larvae persist in tissues, provoking a granulomatous reaction and eventually dying. As a result, abscesses or granulomas form.

Liver is the most involved site, and presents in the form of eosinophilic granulomas or abscesses usually mimicking tumoral processes.6 Eosinophilic granulomas are characterized by hepatic infiltration of eosinophils and other inflammatory cells along with palisade of giant cells and epithelioid histiocytes with central necrosis, whereas, eosinophilic abscess is a lesion containing copious eosinophils along with destroyed liver parenchyma and associated inflammation.5

Lesions are usually described as oval, ill-defined nodules, either unique or more frequently multiple. Imaging reveals multiple clustered complex cystic lesions, best appreciated on portal venous phase, with little or no peripheral enhancement or surrounding edema. These are usually small, less than 2 cm in size and likely to be along the portal vein branches or liver periphery with occasional traversing of the portal vein through the larger lesions. However, we encountered two cases with lesions showing diffusion restriction and distinct peripheral enhancement on portal venous phase and can thus mimic amoebic or pyogenic abscesses. Furthermore, imaging revealed portal vein thrombosis and abscess rupture in two of our patients. To the best of our knowledge, these complications have never been reported in literature in cases of hepatic larva migrans. Treatment with albendazole alone or in combination with ivermectin is reported to be effective,6 although long term therapy is needed for complete eradication.

References

- Chang S, Lim JH, Choi D, Park CK, Kwon NH, Cho SY, Choi DC. Hepatic visceral larva migrans of Toxocaracanis: CT and sonographic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006 Dec;187(6):W622-9.

- Lim JH. Toxocariasis of the liver: visceral larva migrans. Abdom Imaging. 2008 Mar-Apr;33(2):151-6.

- Glickman LT, Magnaval JF, Domanski LM, Shofer FS, Lauria SS, Gottstein B, Brochier B. Visceral larva migrans in French adults: a new disease syndrome? Am J Epidemiol. 1987 Jun;125(6):1019-34.

- Hayashi K, Tahara H, Yamashita K, Kuroki K, Matsushita R, Yamamoto S, Hori T, Hirono S, Nawa Y, Tsubouchi H. Hepatic imaging studies on patients with visceral larva migrans due to probable Ascaris suum infection. Abdom Imaging. 1999 Sep-Oct;24(5):465-9.

- Mukund A, Arora A, Patidar Y, Mangla V, Bihari C, Rastogi A, Sarin SK. Eosinophilic abscesses: a new facet of hepatic visceral larva migrans. Abdom Imaging. 2013 Aug;38(4):774-7.

- Raffray L, Le Bail B, Malvy D. Hepatic visceral larva migrans presenting as a pseudotumor. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 Jun;11(6):e42.