48uep6bbphidcol2|ID

48uep6bbphidvals|1863

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Investigating a patient presenting with gastrointestinal bleed in a tropical country is challenging and we occasion-ally encounter rare causes. Invasive fungal infection due to mucormycosis is one such cause. Massive overt GI bleed as clinical presentation of mucormycosis is very rare.Less than 25% of GI mucormycosis get diagnosed with ante-mortem investigations. The mortality rate is high as these infections are usually seen in immunocompromised patients. This suggests the seriousness of condition and the low awareness. We discuss a case of lower GI bleed secondary to mucormycosis of the caecum.

Case Report

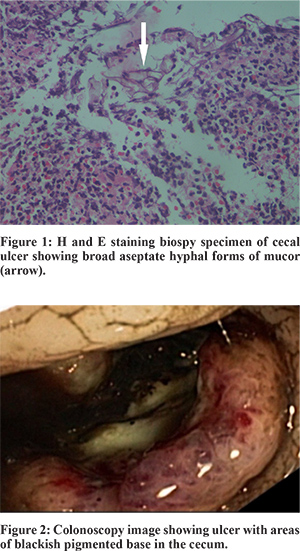

A 41 year old lady was hospitalised with history of lower abdominal pain and loose stools since 1 week and passing large quantity of blood clots mixed with stools since 2 days. No history of hematemesis. She was diagnosed to have rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis due to anti-GBM disease one month prior to this episode. She had received cortico steroids and pulse cyclophosphamide therapy followed by 5 sessions of plasmapheresis. She was on thrice weekly maintenance haemodialysis since then. She was hypotensive and had tachycardia. Pallor was present. Abdominal examination revealed mild hypogastric and periumbilical tenderness. Per rectal examination showed fresh blood. Lab investigations revealed haemoglobin of 4.7 gm/dl and elevated leucocyte count (19,800 cells/cu.mm). After hemodynamic stabilisation and blood transfusion, colonoscopy was done which showed a large 4x5 cms deep cecal ulcer with possible clot/ blackish pigmentation over the base (Figure 1). Ileum appeared normal. Rest of the colonic mucosa was normal. Histopathological examination of biopsies from the cecal ulcer showed broad aseptate hyphal forms consistent with morphology of mucor (Figure 2). She was started on intravenous amphotericin and gradually improved. Her bleeding decreased over the next 2 days and stopped. She was discharged from the hospital but however she was lost for follow-up.

Discussion

Mucormycosis infection is most commonly seen in patients with underlying immunocompromised status like diabetes mellitus, HIV disease, corticosteroid use, underlying hematologic malignancy or post transplant status with immunosuppressant use. Other risk factors are deferoxamine use, military injuries (blast injuries) and natural disasters.1

Mucormycosis can manifest in humans in 5 different forms: rhinocerebral, pulmonary, cutaneous, gastrointestinal and disseminated forms. Gastrointestinal involvement is rare and seen in 7% of cases.2 Stomach is the most common organ involved followed by colon and ileum. Clinical presentation of GI mucormycosis is nonspecific with symptoms ranging from abdominal discomfort, diarrhoea, perforation and bleeding. GI involvement is more common in infants. Most common cause of mortality is bowel perforation. Presentation with massive lower GI bleed is rare.3 Mucormycosis invades the GI mucosa and submucosa and classically causes thrombosis of endarteries. This leads to necrosis and ulcers of the GI mucosa. The ulcers have been described aslarge deep well demarcated with exudative base and rarely eschar like pigmentation. Rarely proliferative lesions mimicking malignancy have been described.4

Diagnosis is usually by histopathology and there are no clinical pathognomonic features. Only 25-50% of the cases are diagnosed antemortem.5 Presence of aseptate hyphal forms of the fungus in a background of mononuclear infiltrate is seen in the histopathological specimens. Treatment depends on depth of involvement, clinical manifestation and general condition of patients. Extensive debridement of the area and liposomal amphotericin B are often required in severe cases.Survival was 3% for cases that were not treated, 46-61% for cases treated with amphotericin B deoxycholate, 57% for cases treated with surgery alone, and 70%-81% for cases treated with amhotericin B and surgery.5

We discuss this case to highlight the need to maintain a high index of suspicion for unusual opportunistic infections as cause of GI bleed in immunocompromised patients.

References

- Ibrahim AKontoyiannis D. Update on mucormycosis pathogenesis. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 2013;26(6):508-515. doi:10.1097/qco.0000000000000008.

- Roden M, Zaoutis T, Buchanan W et al. Epidemiology and Outcome of Zygomycosis: A Review of 929 Reported Cases. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2005;41(5):634-653. doi:10.1086/432579.

- Sakorafas G, Tsolakides G, Grigoriades K, Bakoyiannis C, Peros G. Colonic mucormycosis: An exceptionally rare cause of massive lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Digestive and Liver Disease. 2006;38(8):616-617. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2006.03.018.

- Rodrigues S, Santos L, Nuak J, Pardal J, Sarmento J, Macedo G. Colonic mucormycosis. Endoscopy. 2013;45(S 02):E20-E20. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1326110.

- Chakrabarti A, Das A, Sharma A et al. Ten Years’ Experience in Zygomycosis at a Tertiary Care Centre in India. Journal of Infection. 2001;42(4):261-266. doi:10.1053/jinf.2001.0831.