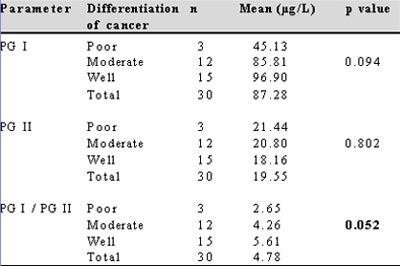

Table III: Correlation of serum PG I, PG II and PG I/II values with the degree of differentiation of carcinoma stomach

PG-pepsinogen

DISCUSSION

Serum pepsinogen has gained much attention recently as a useful diagnostic tool in screening for gastric carcinoma.(8) However, its role in disorders like H.pylori gastritis, peptic ulcer, portal hypertensive gastropathy, erosive gastritis and non-ulcer dyspepsia is uncertain.

There is wide variation in the levels of serum PG I, PG II and PG I/II in normal individuals across different population groups. The range varies from 40-80 µg/L for PG I, 10-15 µg/L for PG II and 5-9 for PG I/II ratio in different population groups.(9,10,11) The mean levels of PG I (158 µg/L) and PG II (22 µg/L) in normal individuals in the present study were much higher than those reported in other studies. The ratio of PG I/II (7.2) however was similar. The reason for a higher level of PG I and II in the population studied is outside the scope of the present study, but may be linked to the chief cell mass in different population groups.

The present study demonstrated a significant fall in the levels of PG I and PG I/II ratio in patients with carcinoma stomach. A similar decrease in PG I and PG I/II levels in carcinoma stomach has been noted in studies across literature.(4,12) Only one study from Singapore by So et al found the ratio of PG I/II alone to be decreased in carcinoma stomach with no change in the levels of PG I or PG II.(13) The absence of a fall in PG I in their study could be due to the low prevalence of atrophic gastritis and gastric carcinoma in the population studied by them. No significant association between PG II levels and carcinoma stomach was found in the present study. This is explained by the additional duodenal secretion of PG II which compensates for its decreased supply from the gastric source.

Reliable cut off points of PG I level and PG I/II ratio for detecting carcinoma stomach can be calculated using the ROC curve. The calculated levels in literature range from 25-70 µg/L for PG I and 3-5 for PG I/II.(12,14) In the present study the cut off level, to diagnose carcinoma stomach, of serum PG I was 115.3 µg/L and for PG I/II ratio was 6.25. When both tests, i.e. PG I and PG I/II ratio were used in parallel the sensitivity was 97.0% and the negative predictive value was 91.4%. Using the two tests in series the sensitivity declined to 72.2%.The sensitivity and specificity of these levels in detecting carcinoma stomach are comparable to the previous studies.

The predictive values of any diagnostic test are dependent on the prevalence of the disease in the population studied.(15) Hence to obtain a more reliable way of assessing the usefulness of a test the sensitivity and specificity can be combined into one measure called the Likelihood Ratio (LR).When test results are reported as being either positive or negative two types of LRs can be described, viz, likelihood ratio for a positive test, LR (+), and the likelihood ratio of a negative test, LR (-). A low LR(-) rules out disease.

The LR(-)value was 0.06 when the PG I level and PG I/II ratio were applied in parallel, indicating that individuals without carcinoma were 16 times more likely to have a negative test than those with carcinoma, thus making it a good screening test.

Various studies have attempted to elucidate the correlation between pepsinogen levels and H.pylori infection with conflicting conclusions.(16) Studies have found serum PG II levels to be raised in H.pylori infection and have recommended the use of serum PG II levels to diagnose and to evaluate eradication of H.pylori infection.(5,17) On the contrary other studies have found an elevated serum PG I over PG II in H.pylori infection.(18) In the present study there was no significant change in PG I, PG II or the PG I/II ratio in patients with H.pylori gastritis. A diagnosis of H.pylori gastritis was made by urease testing alone. It is known that H.pylori can cause an increased pepsinogen level during the initial phase of mucosal inflammation with a subsequent fall in its levels as the inflammation progresses to atrophy. Since there was no histological correlation of H.pylori gastritis with pepsinogen levels in the present study, our results may not be conclusive.

There exists no conclusive evidence regarding the association between peptic ulcer and pepsinogen level. Studies have described elevated PG I/II ratio in duodenal ulcer. Duodenal ulcer is also shown to have a high PG I level.4 Other studies have found increased PG I level in gastric ulcer rather than duodenal ulcer.(19) In the present study, we found no significant association between peptic ulcer and serum pepsinogen levels.

Very few studies are available on the role of pepsinogen in portal gastropathy with no demonstrable relationship between them.(20) This was our observation as well. We found no correlation between serum PG I and PG II levels with erosive gastritis and NUD. Studies done earlier have found no relationship between pepsinogen level and erosive gastritis.(9) There exists no conclusive data in the literature about the relationship between NUD and PG levels.

From this study, we conclude that estimation of serum pepsinogen level is a reliable tool in screening for carcinoma stomach. Patients with abnormal values may be selected for endoscopy. There was no significant change in serum pepsinogen levels in disorders like peptic ulcer, portal hypertensive gastropathy, NUD, erosive gastritis and H.pylori gastritis; thus the role of serum pepsinogen level in the diagnosis of these disorders was not established.

The main limitations of the present study were a relatively small sample size, lack of severity grading of gastritis leading to an inability to correlate the levels with severity of gastritis, and inadequate number of patients in subgroups of carcinoma stomach for valid comparisons to be made between different degrees of differentiation. Also, since we had no patients with early gastric carcinoma we could not assess the utility of these values in early gastric cancer.

REFERENCES

1. Samloff IM, Varis K, Ihamaki T, Siurala M, Rotter JI. Relationship among serum pepsinogen I, serum pepsinogen II and gastric mucosal histology: a study in relatives of patients with pernicious anemia. Gastroenterology. 1982;83:204–9.

2. Samloff IM. Pepsinogen, pepsins and pepsin inhibitors. Gastroenterology. 1971;60:586–604.

3. Fukao A, Hisamichi S, Ohsato N, Fujino N, Endo N, Iha A. Correlation between the prevalence of gastritis and gastric cancer in Japan. Cancer Causes Control. 1993;4:17–20.

4. Huang SC, Miki K, Furihata C, Ichinose M, Shimizu A, Oka H. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for serum pepsinogen I and II using monoclonal antibodies – with data on peptic ulcer and gastric cancer. Clin Chim Acta. 1988;175:37–50.

5. Di Mario F, Moussa AM, Cavallaro LG, Caruana P, Merli R,Bertolini S, et al. Clinical usefulness of serum pepsinogen II in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Digestion. 2004;70:167–72.

6. Kikuchi S, Kurosawa M, Sakiyama T, Tenjin H. Long-term effect of smoking on serum pepsinogen levels. J Epidemiol. 2002;12:351–6.

7. Festen HP, Thijs JC, Lamers CB, Jansen JM, Pals G, Frants RR, et al. Effect of oral omeprazole on serum gastrin and serum pepsinogen I level. Gastroenterology. 1984;87:1030–4.

8. Webb PM, Hengels KJ, Moller H, Newell DG, Palli D, Elder JB, et al. The epidemiology of low serum pepsinogen A levels and an international association with gastric cancer rates EUROGAST Study Group. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1335–44.

9. Ichinose M, Miki K, Furihata C, Kageyama T, Hayashi R, Niwa H, et al. Radioimmunoassay of serum group I and group II pepsinogens in normal controls and patients with various disorders. Clin Chim Acta. 1982;126:183–91.

10. Wu MS, Lin JT, Wang JT, Huang SC, Wang CY, Wang TH. Serum levels of pepsinogen I in healthy volunteers and patients with gastric ulcers and gastric carcinoma in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 1993;92:711-6.

11. Veenendaal RA, Biemond I, Pena AS, Van Duijn W, Kreuning J, Lamers CB. Influence of age and Helicobacter pylori infection on serum pepsinogen in healthy blood transfusion donors. Gut. 1992; 33:452–5.

12. Kitahara F, Kobayashi K, Sato T, Kojima Y, Araki T, Fujino MA. Accuracy of screening for gastric cancer using serum pepsinogen concentrations. Gut. 1999;44:693–7.

13. So JB, Yeoh KG, Moochala S, Chachlani N, Ho J, Wong WK, et al. Serum pepsinogen levels in gastric cancer patients and their relationship with Helicobacter pylori infection: a prospective study. Gastric cancer. 2002;5:228–32.

14. Aoki K, Misumi J, Kimura T, Zhao W, Xie T. Evaluation of cut off levels for screening of gastric cancer using serum pepsinogens and distributions of levels of serum pepsinogen I, II and of PG I/PG II ratios in a gastric cancer case-control study. J Epidemiol. 1997;7:143–51.

15. Akobeng KA. Understanding diagnostic tests 2: likelihood ratios, pre-and post-test probabilities and their use in clinical practice. Acta Paediatrica. 2007;96:487–91.

16. The EUROGAST Study Group. An international association between Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer. Lancet. 1993;341:1359–62.

17. Bodger K, Wyatt JI, Heatley RV. Variation in serum pepsinogens with severity and topography of Helicobacter pylori – associated chronic gastritis in dyspeptic patients’ referred for endoscopy. Helicobacter 2001;6:216–24

18. Mossi S, Meyer-Wyss B, Renner EL, Merki HS, Gamboni G. Influence of Helicobacter pylori, sex and age on serum gastritis and pepsinogen concentrations in subjects without symptoms and patients with duodenal ulcers. Gut. 1993;34:752–6.

19. Wu MS, Wang HP, Wang JT, Wang TH, Lin JT. Serum pepsinogen I and pepsinogen II and the ratio of pepsinogen I/II in peptic ulcer diseases: with special emphasis on the influence of the location of the ulcer crater. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1995;10:401–4.

20. Lin WJ, Lee FY, Lin HC, Tsai YT, Lee SD, Lai KH, et al. Snake skin pattern gastropathy in cirrhotic patients. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1991;6:145–9.