Rohit Gupta1, Sourav Das2, Ravi Gupta2, Vivek Ahuja1, Manju Saini3, Mohan Dhyani2

Departments of Gastroenterology1

Psychiatry & Sleep Clinic2, Radiodiagnosis3

Himalayan Institute of Medical Sciences,

Swami Ram Nagar, Doiwala

Dehradun 248140, India

Corresponding Author:

Dr Rohit Gupta

Email: doctorrohitgupta@yahoo.co.in

48uep6bbphidvals|1367 48uep6bbphidcol2|ID 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Marchiafava Bignami disease (MBD) is a rare disorder, first described in 1903 by Marchiafava and Bignami and characterized by primary progressive demyelination and necrosis of corpus callosum presenting clinically with multifocal central nervous system signs along with altered mental status and seizures.[1] The exact pathology leading to MBD has not yet been elucidated. Classically, chronic alcoholism and vitamin deficiency have been implicated. Recently, MBD is hypothesized to result from an autoimmune insult or part of a para-neoplastic syndrome.[2,3]

Here, we present the case of a 33-year old male who had history of chronic alcoholism with acute pancreatitis presenting with MBD.

Case report

A 33-year old male patient with history of daily intake of upto 150mL of alcohol for 20 years presented to the emergency with acute onset confusion, decreased speech, hyporesponsiveness, difficulty in recognizing family members and seizures for 2 days.

6 weeks ago, he complained of severe pain in abdomen, sweating, severe vomiting and agitation after an episode of heavy drinking. After 2 days, he developed ascites, constipation and urinary retention. His serum amylase and serum lipase levels were raised and contrast enhanced computerized tomography (CECT) scan of the abdomen showed the presence of pancreatic necrosis (> 50% of pancreatic parenchyma) with presence of necrotic fluid collections in lesser sac and right para-colic gutter.

10 days later, he suddenly developed two episodes of generalized seizures within 15 minutes. After the seizures, he became unresponsive, drowsy, confused, and disoriented. He was talking irrelevantly, but could gesture urge to defecate and micturate and had to be assisted in doing so.

On the next evening, he was brought to the emergency department of our hospital, where on examination, he was found to be delirious. There was spontaneous eye movement, purposeful movement to painful stimulus and inappropriate responses with discernible words (GCS 4 + 3 + 5= 12). He had ascites and tender upper abdomen, but was afebrile, with stable vitals without signs of meningeal involvement and focal neurological deficit. Routine blood investigations, electrolytes, HIV, Hepatitis B and C were normal including INR. Ascitic fluid was exudative with elevated amylase (2586U/L). CSF examination (biochemical, microscopy, ADA level, and India Ink preparation) was normal.

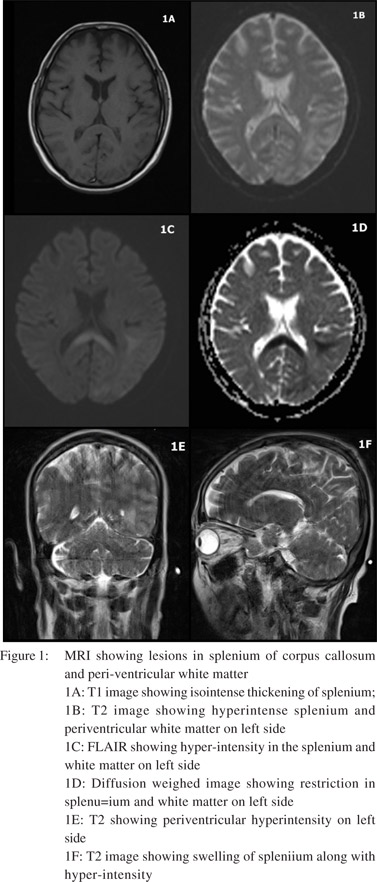

Non Contrast CT Scan (NCCT) brain showed mild atrophy. T2 sequence of axial and sagittal images of MRI scan of brain revealed swelling and hyperintensity of splenium of corpus callosum. Hyperintensity in subcortical white matter regions of temporal, occipital and parietal lobes of left side were seen along with periventricular white matter hyper-intensity along left ventricular trigone. This was iso-intense on T1 with effacement of intervening sulci which showed restriction on diffusion weighed imaging (DWI) (Figure 1).

The patient was diagnosed as a case of acute pancreatitis with alcohol dependence syndrome with MBD. He was managed conservatively with i.v. fluids, antimicrobials, analgesics and multivitamins containing thiamine 200 mg/ day. After 2 weeks, clinical improvement was noted with GCS of 15/15, relevant and coherent speech and orientation was partially improved. After 3 weeks,his mental functioning returned to baseline.

Discussion

This case presented with altered sensorium and seizures with acute pancreatitis and chronic alcoholism. Hence, the differential diagnosis included delirium tremens, fluid electrolyte imbalance, meningo-encephalitis, thromboembolic stroke, pancreatic encephalopathy (PE), Wernicke’s encephalopathy (WE) and MBD.

Last alcohol intake being a month ago ruled out delirium tremens, which usually occurs within 48-96 hours after last or reduced intake. Normal serum electrolytes, absence of signs of meningeal irritation and normal CSF examination ruled out delirium due to electrolyte imbalance or meningo-encephalitis. Thrombo-embolic stroke was ruled out by lack of any focal neurological deficit, CT scan findings and the location of lesions on MRI.

PE is a common complication of severe pancreatitis, presenting as confusion, restlessness, and associated with diffuse demyelination and white matter changes on cerebral imaging.[4] Since the white matter changes were not similar to PE, it was excluded.

WE and MBD occur frequently among alcoholics and may co-exist. It is sometimes difficult to differentiate between them clinically. The diagnosis of WE is primarily clinical and presence of any of the two of the following: eye signs, cerebellar signs, dietary deficiency and memory impairment or altered mental functions, has been observed as 85% sensitive. This patient had altered mental status and possibly dietary deficiency but, cerebellar signs could not be established. However, nystagmus was not seen on examination. Thus, WE could not be ruled out clinically. On the other hand, clinical diagnosis of MBD was supported by altered sensorium, seizures and confusion.[1]

MRI brain can reliably differentiate the two conditions. Lesions in WE associated with alcoholism are bilaterally symmetrical and often involve mamillary bodies, thalamus, tectal plate and peri-aqueductal grey.[5] Swelling and T2 hyperintensity of splenium of corpus callosum and extracallosal regions with restriction on DWI in this case supported the diagnosis of MBD.[5] MBD lesion may extend into genu and adjacent white matter of corpus callosum. MBD is often misdiagnosed as WE, and this might be one reason why involvement of the corpus callosum has been reported in atypical cases of WE. It may also be possible that WE and MBD are etiologically same and lie in a spectrum with involvement of different brain areas giving rise to different clinical features.

Our patient might have developed MBD due to alcohol related neurotoxicity or due to a thiamine deficient state caused by alcohol or severe vomiting. An interesting alternative hypothesis in this case is that the resultant pro-inflammatory state created by the acute pancreatitis might have resulted in the MBD by means of a yet unknown cascade of immunogenic mechanism.

The diagnosis and prevalence of MBD may increase with increasing use of routine neuroimaging all over the world. MBD should be kept as a differential diagnosis in all cases of WE and in those with chronic alcoholism and/or inflammatory conditions presenting with altered sensorium and cognitive impairment.

References

- Hoshino Y, Ueno Y, Shimura H, Miyamoto N, Watanabe M, HattoriN et al. Marchiafava-Bignami disease mimics motor neuron disease: case report. BMC Neurology. 2013;13:208.

- Celik Y, Temizoz O, Genchellac H, Cakir B, Asil T. A non-alcoholic patient with acute Marchiafava-Bignami disease associated with gynecologic malignancy: paraneoplastic Marchiafava-Bignami disease? Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2007;109:505–8.

- Furukawa K, Maeshima E, Maeshima S, Ichinose M. Multiple symptoms of higher brain dysfunction caused by Marchiafava- Bignami disease in a patient with dermatomyositis. Rheumatol Int. 2011;31:109–12.

- Zhang XP, Tian H. Pathogenesis of pancreatic encephalopathy in severe acute pancreatitis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2007;6:134–40.

- Bano S, Mehra S, Yadav SN, Chaudhary V. Marchiafava-Bignami disease: Role of neuroimaging in the diagnosis and management of acute disease. Neurol India. 2009;57:649–52.

|