48uep6bbphidcol2|ID

48uep6bbphidvals|3016

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a condition characterized by an excess of fat in the liver without excess alcohol intake.1 It ranges from simple steatosis to steatohepatitis and can lead to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in the long run. In western countries, NAFLD is a common cause of chronic liver disease and liver transplantation. The overall prevalence of NAFLD is 15-40% in western countries and 9-40% in Asian countries.2 Metabolic syndrome and its associated conditions like diabetes, obesity, and dyslipidaemia are predisposing factors for NAFLD. Due to the rising incidence of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and insulin resistance among the Indian population in the last two decades, NAFLD is becoming a major public health problem in India.3,4 However, the data on the prevalence of NAFLD from India is limited.5,6

NAFLD in its initial stages of hepatic steatosis is a reversible condition. It is often associated with obesity and metabolic syndrome, the treatment of which involves lifestyle modification and weight reduction. Only those who are morbidly obese and have steatohepatitis require bariatric surgery or pharmacotherapy for weight reduction. However, when neglected, NAFLD can progress to liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, which are irreversible and require liver transplantation. Following alcoholic liver disease and HCV hepatitis, NAFLD is the most common indication for liver transplantation in the United States and the only indication showing an increasing trend.7

By 2016, India had entered stage 1 of the obesity transition, wherein the average prevalence of obesity among women was higher than that of men (10% vs. 4%), and the prevalence was higher in adults than in children (7% vs. 2%). Stage 1 is also characterized by higher prevalence among higher socioeconomic status, especially women.8

This study was done to find the prevalence of this disease in the nursing staff of our institute, which is a population comprising predominantly of women of higher socioeconomic status who lead a sedentary lifestyle. In addition, it was also done to study the prevalence of known risk factors of NAFLD in this population and their association with NAFLD.

Method

The study was an institute-based cross-sectional analytical study.

The study was carried out among the nursing staff of our institute from September 2015 to August 2017 after obtaining clearance from the Postgraduate Research Monitoring Committee (PGRMC) and the Institute Ethics Committee (Human Studies).

All permanent nursing staff above the age of 18 years were assessed for eligibility for the study. The subjects with a past history of jaundice, liver disease, consumption of significant dosage of hepatotoxic drugs in the past, alcohol consumption >140g/week among men and >70g/week among women in the past and with serum HBsAg or anti-HCV positivity were excluded from the study.

Assuming a prevalence of 19% NAFLD among nursing staff, similar to a study in an urban railway population by Amarapurkar, with absolute precision of 5% and 95% confidence interval, the sample size for the study was calculated as 144 using OPENEPI® software version 3.0.9.

Following approval from Institute Ethics Committee, the subjects for the study were approached by a convenience sampling method owing to practical difficulty with systematic random methods. All nursing staff who gave consent for being a part of the study were further assessed for eligibility to be included in the study. A total of 210 nursing staff thus approached gave consent to be further assessed.

Pre-tested interview schedules were used to collect details from the study participants. The proforma included questions regarding their demographic details and intake of alternative medication/supplements, prior history of jaundice, liver disease, alcohol consumption, and history of diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidaemia. The subjects who had a history that satisfied any of the exclusion criteria were not further assessed.

The recruited subjects underwent thorough physical examination and anthropometric measurements, including height, weight, blood pressure, waist, and hip circumferences. A second visit was planned for withdrawing blood after 8 hours of fasting.

About 5 ml of blood was withdrawn from the antecubital vein under aseptic precautions, and it was used to measure fasting blood sugar, fasting lipid profile, serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) alanine aminotransferase (ALT), HBsAg, and anti HCV serology. The investigation reports were collected, subjects who tested positive for HBsAg or anti-HCV were excluded, and the remaining underwent an ultrasound examination.

Of the nursing staff, four were excluded, and 56 did not follow up for either fasting blood investigations or ultrasound imaging. Thus, a total of 150 eligible subjects underwent complete blood investigations and abdominal ultrasounds.

All subjects diagnosed with NAFLD by ultrasound were counselled regarding lifestyle changes, emphasizing dietary modifications and increased physical activity to lose weight. All subjects diagnosed with diabetes, dyslipidaemia, or metabolic syndrome were also counselled and directed to departments of general medicine and endocrinology for further workup and management.

Results

A total of 210 nursing staff were approached and assessed as part of the present study, of which four were excluded after applying inclusion-exclusion criteria of whom one had a significant intake of hepatotoxic drugs (oral steroids for more than six months), one was HBsAg positive, two had pre-existing liver disease (Gilbert’s syndrome and progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis). Of the remaining eligible subjects, 150 who completed blood investigations and underwent an ultrasound abdomen were analysed.

The maximum number of subjects among the nursing staff was between 21 to 30 years of age. In our study, 63.3% were females. On studying the BMI, 54% of the subjects were obese, 22% were overweight, and 2% were underweight. Only 22% had a normal BMI.

The risk factors for NAFLD, such as abdominal obesity was present in 40.7% of the subjects, 9.3% had diabetes, and 3.3% had hypertension. Dyslipidaemia and metabolic syndrome were diagnosed in 46.7% and 18%, respectively.

A total of 107 patients (71.3%) of the total subjects had a normal liver by ultrasonography. Of the remaining 43 subjects, 31 (20.7 %) had mildly fatty, 10 (6.7%) had moderately fatty, and 2 (1.3%) had severely fatty liver.

The prevalence of NAFLD as seen by ultrasound imaging was 28.7%. There was a significant association (p=0.029) of increasing age with NAFLD, and the prevalence of NAFLD was the maximum (53.8%) among those more than 50 years of age. There was a higher prevalence of NAFLD in females, but the difference between the two genders was insignificant. Higher BMI (p<0.001) and abdominal obesity (p<0.001) were significantly associated with NAFLD in the present study (Table 1).

The mean age in the total population studied was 34.2 years, and it was significantly higher in those with NAFLD (p=0.014). The means of other physical examination parameters were as follows; BMI 25.7 kg/m2, waist circumference 85.5 cm (males) and 81.6 cm (females), systolic blood pressure 114.5 mmHg, and diastolic blood pressure 72.4 mmHg. These were significantly higher in the NAFLD group (p<0.05) (Table 2).

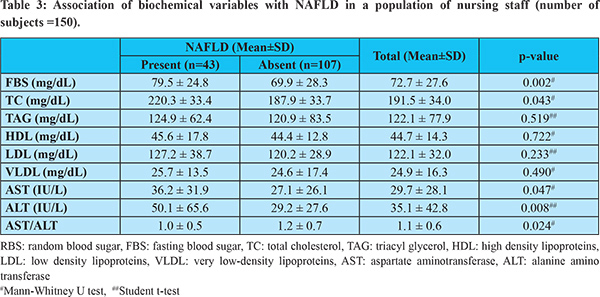

The mean values of biochemical parameters like fasting blood sugar (72.7 mg/dL), total cholesterol (191.5 mg/dL), triglyceride (122.1 mg/dL), aspartate aminotransferase (29.7 IU/L), alanine aminotransferase (35.1 IU/L), and AST/ALT ratio (1.1) were significantly higher in the subjects with NAFLD (Table 3).

Table 4 shows the association between various risk factors and NAFLD. Prevalence ratios (PR) were calculated to identify the association between the various risk factors and NAFLD in the present study. The prevalence of the primary outcome, i.e., NAFLD, being high in the present study (28.7%), prevalence ratios provide a more accurate estimate of the association when compared to odds ratios. The risk factors with significant association with NAFLD were age >40 years (PR 2.1, p=0.012), obesity (PR 3.8, p<0.001), abdominal obesity (PR 3.0, p<0.001), dyslipidaemia (PR 1.7, p=0.049), and metabolic syndrome (PR 1.8, p=0.045). Hypertension and diabetes mellitus did not show significant association with NAFLD in this study.

Discussion

NAFLD is currently the most common cause of liver disease in Western countries.7 In India, all studies on NAFLD have been conducted in the general population. No studies are there in the medical community. It was conducted among a sedentary population, which has an increased risk for developing insulin resistance, which is the core of the pathogenesis of NAFLD and the risk factors for NAFLD.

The mean age of the population studied was 34.2 years which was lower than that of the populations studied by Amarapurkar et al., Mohan et al., and Majumdar et al., which were 39 years, 42 years, and 45 years respectively.9-11 The subjects in the present study were mostly females (63.3%), unlike other studies, which showed a predominance of males.9,11 These studies were conducted in the general population, while the present study was conducted among the nursing staff of our institute, of whom the majority were females.

The prevalence of NAFLD among the nursing staff in the present study was 28.7%. The prevalence of NAFLD ranges from 9% to 47.6% in various studies across the world.

Out of the 150 subjects, 43 had NAFLD, of whom 72.1% (n=31, 20.7% of the total population) had mildly fatty liver, 23.3% (n=10, 6.7% of the total population) had moderately fatty liver, and 4.7% (n=2, 1.3% of the total population) had a severely fatty liver. These findings were similar to the study by Majumdar et al., which reported mild fatty liver in 74.1%, moderate fatty liver in 22.2%, and severe fatty liver in 3.7%.11

The prevalence of NAFLD was higher in females (29.5%) than males (27.3%) in the present study. However, this difference was not significant. In the study by Majumdar et al. there was significant male preponderance (33.0% versus 30.1%, p=0.27) which was also seen in the studies by Amarapurkar et al. (24.6% vs 13.6%, p<0.001), Williams et al. (58.9% vs 41.1%, p=0.001) and Zeller-Sagi et al. (38.0% vs 21.0%, p=0.001).9,11-13 The higher prevalence among females in our study could be because most of the subjects involved in our study were the female nursing staff. Further studies with an adequate sample size are necessary to assess the gender predisposition to NAFLD in the population studied.

The prevalence of NAFLD was higher in the higher age groups, and the differences were significant (p=0.029). The mean age of the two groups showed a significant difference, i.e., 37 years in subjects with NAFLD versus 33 years in those without NAFLD (p=0.014). This was comparable to the study by Das et al., wherein a mean age of 39 years in NAFLD was reported compared to 35 years in those without NAFLD.14 When the prevalence ratio was calculated in the present study, there was a significant association between age more than 40 years and NAFLD. The risk of NAFLD among those over 40 years was twice the risk in those less than or equal to 40 years. The study by Amarapurkar et al. also showed a significant association of age more than 40 years with NAFLD.9

The mean BMI of the studied population was 25.7 kg/m2. The majority of the population in the present study was obese (BMI = 25 kg/m2), and its prevalence was 54%. This was higher than the national average of 18 to 20%.10 The sedentary lifestyle prevalent among the nursing staff may have contributed to the higher BMI. The mean BMI was higher in subjects with NAFLD (28.4 kg/m2 vs. 24.7 kg/m2), and the difference was significant (p<0.001). Similar results were reported by Das et al. (25.3 kg/m2 vs. 22.8 kg/m2, p=0.002) and Mohan et al. (25.2 kg/m2 vs. 22.9 kg/m2, p<0.001).10,14 The prevalence of NAFLD in this study was significantly higher in the subjects with higher BMI (p<0.001).

The mean waist circumference of the subjects in the present study was 85.5 cm for males and 81.6 cm for females. The mean waist circumference of the subjects with NAFLD was higher than those without NAFLD, and the difference was significant among both males (88.4 cm vs. 84.4 cm, p=0.010) and females (88.7 cm vs. 78.7 cm, p<0.001). In the South Indian urban population study by Mohan et al., a similar increase in the waist circumference was seen among subjects with NAFLD (males: 92.4 cm vs. 86.5 cm, p<0.001 and females: 87.8 cm vs. 81.9 cm, p<0.001).10

The prevalence of abdominal obesity, defined as “waist circumference more than 80 cm in females and 90 cm in males,” was 40.7%. This was lower compared to the study by Amarapurkar et al. (57%) and higher than that reported by Das et al. (39%).9,14 The former study was conducted in an urban population, while Das et al. did the study among a rural population. This explains the difference in the prevalence of abdominal obesity among the urban and rural locales. Abdominal obesity has also been shown to increase with increasing age 15 In the present study, most of the subjects belonged to a younger age group compared to the study by Amarapurkar et al., which explains the lower prevalence of abdominal obesity in this study.9

Obesity due to increased BMI, and abdominal obesity, due to increased waist circumference cause insulin resistance, which increases hepatic triglyceride and fatty acid deposition. It also causes oxidative damage to the hepatocytes. These processes initiate hepatic steatosis and NAFLD.16,17 The present study showed that the prevalence of NAFLD was significantly more among the subjects who were obese. The study also reported a similar association among subjects who had abdominal obesity. The risk of NAFLD among those with obesity was four times more than those who were not obese. Among the subjects who had abdominal obesity, the risk of NAFLD was three times more than those who did not have abdominal obesity. The odds ratios of association of obesity and abdominal obesity with NAFLD were 6.0 (95% C.I. 2.6-14.2) and 4.9 (95% C.I. 2.3-10.4), respectively. These were similar to the study by Majumdar et al., which reported odds ratios of 5.5 (95% C.I. 2.6-11.7, p<0.001) for obesity and 5.7 (95% C.I. 2.8-11.3, p<0.001) for abdominal obesity.11 The studies by Amarapurkar et al. and Jimba et al. also reported a significantly higher prevalence of NAFLD among subjects with obesity (BMI>25kg/m2) or abdominal obesity with NAFLD.9,18

In the studied population, the mean systolic blood pressure (SBP) was 114.5 mmHg, and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) was 72.4 mmHg. The mean SBP (117.5 mmHg vs. 113.3 mmHg, p=0.038) and the mean DBP (75.7 mmHg vs. 71.1 mmHg, p=0.002) were higher among the subjects with NAFLD. The prevalence of hypertension in the studied population, as assessed by history, was 3.3 %. There was no significant association between NAFLD and hypertension.

In the studies on NAFLD by Das et al., Amarapurkar et al., and Mohan et al., hypertension was not a significant risk factor in NAFLD, correlating with the present study.9,10,14 Pathogenesis of NAFLD is initiated by factors that cause insulin resistance, and hypertension has not been shown to have such a role in the action of insulin and lipid metabolism.

The mean fasting blood sugar (FBS) in the study population was 72.7 mg/dL. It was significantly higher in subjects with NAFLD than those without it (79.5 mg/dL versus 69.9 mg/dL, p=0.002). This was similar to the study by Amarapurkar et al., which showed a significant association between increased FBS and NAFLD.9

The prevalence of diabetes in the population studied was 9.3%, and it had no significant association with NAFLD. This was in contrast to the study by Amarapurkar et al., which reported diabetes as an independent risk factor.9 The studies by Majumdar et al., Das et al., and Mohan et al. also reported a significant association between NAFLD and diabetes.10,11,14 In the present study, postprandial blood sugars or HbA1c were not assessed, so this entity could have been underdiagnosed. Further studies are required to assess the association of diabetes with NAFLD in this population.

Dyslipidaemia was diagnosed in the present study based on NCEP-ATP III guidelines, i.e., Total cholesterol (TC) =200 mg/dL, Triacylglycerol (TAG) = 150 mg/dL, or High-density lipoproteins (HDL) <40 mg/dL in males or <50 mg/dL in females.19 In the population studied, 46.7 % of the subjects had dyslipidaemia. These included subjects who had been previously diagnosed with dyslipidaemia and those who were newly diagnosed. The mean TC in the studied population was 191.3 mg/dL, significantly higher in those with NAFLD (p=0.043). The mean TAG, HDL, LDL, and VLDL were higher in the subjects with NAFLD, but the difference was not significant.

There was a significant association between dyslipidaemia and NAFLD (PR 1.7; C.I. 1.0-2.9), OR 2.2; C.I. 1.1-4.5, p=0.049. The risk of NAFLD being present among the subjects with dyslipidaemia was 1.7 times higher than those without dyslipidaemia, as assessed by the prevalence ratio. The odds of NAFLD being present among those with dyslipidaemia was twice compared to those without dyslipidaemia. Majumdar et al. also reported a significant association of NAFLD with increased TC (OR 2.5, 95% C.I. 1.1-5.6, p=0.03). However, the association of increased TAG was not significant (OR 2.3, 95% C.I. 0.99-5.2, p=0.05). This study by Majumdar et al. also showed a protective association between normal HDL and NAFLD (OR 0.4, 95% C.I. 0.2-0.8, p= 0.001).11

Metabolic syndrome was diagnosed using the South Asian Modified National Cholesterol Education Programme (SAM-NCEP) criteria. Its prevalence in the studied population was 18 %. The association of NAFLD with metabolic syndrome was significant in the present study (PR 1.8, 95% C.I. 1.1-3.0; OR 2.4 95% C.I. 1.0-5.6, p=0.045). Among the subjects with metabolic syndrome, there was a 1.8 times higher risk of NAFLD being present when compared to those without metabolic syndrome, as assessed by the prevalence ratio. The odds of getting NAFLD in those with metabolic syndrome in the studied population were similar to the reports from the study by Lavekar et al. (OR 1.84, 95% C.I. 0.89-3.8, p=0.10). Mohan et al. showed a higher association of metabolic syndrome with NAFLD (OR adjusted for age and gender 2.8, 95% C.I. 1.9-4.2, p<0.001).10,20

Conclusion

The results of this study may be used to advise routine screening of all nursing staff and especially those aged more than 40 years or who have any of the other risk factors like obesity, abdominal obesity, dyslipidaemia, or metabolic syndrome, for the presence of NAFLD. At risk individuals should be encouraged to modify dietary habits and incorporate adequate physical activity in their daily routine, to avoid the development of these risk factors, which can predispose them to NAFLD. Understanding this pattern of obesity transition will guide future research, provide context for policymaking and a community-based approach in obesity prevention, thereby aiming to achieve the WHO target of halting the rise in the prevalence of obesity by 2025.

References

- Abdelmalek MF, Diehl AM. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Diseases and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. In: Kasper DL, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J, editors. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine 19th ed. New Delhi: Mc Graw Hill; 2016. p. 2054-57.

- Angulo P. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2002; 346:1221–31.

- Chitturi S, Farrell GC, Hashimoto E, Saibara T, Lau GKK, Sollano JD. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in the Asia-Pacific region: definitions and overview of proposed guidelines. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007; 22:778–87.

- Williams R. Global challenges in liver disease. Hepatol Baltim Md. 2006; 44: 521–6.

- Singh SP, Nayak S, Swain M, Rout N, Mallik RN, Agrawal O, et al. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in coastal eastern India: a preliminary ultrasonographic survey. Trop Gastroenterol. 2004;25:76–9.

- Duseja A. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in India – a lot done, yet more required! Indian J Gastroenterol. 2010;29:217–25.

- Zezos P, Renner EL. Liver transplantation and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(42):15532–8.

- Jaacks LM, Vandevijvere S, Pan A, McGowan CJ, Wallace C, Imamura F, et al. The obesity transition: stages of the global epidemic. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology 2019; 7(3):231-40.

- Amarapurkar D, Kamani P, Patel N, Gupte P, Kumar P, Agal S, et al. Prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: population based study. Ann Hepatol. 2007; 6:161–3.

- Mohan V, Farooq S, Deepa M, Ravikumar R, Pitchumoni CS. Prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in urban south Indians in relation to different grades of glucose intolerance and metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2009;84:84–91.

- Majumdar A, Misra P, Sharma S, Kant S, Krishnan A, Pandav CS. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in an adult population in a rural community of Haryana, India. Indian J Public Health. 2016;60:26.

- Williams CD, Stengel J, Asike MI, Torres DM, Shaw J, Contreras M, et al. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis among a largely middle-aged population utilizing ultrasound and liver biopsy: a prospective study. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:124–31.

- Zelber-Sagi S, Nitzan-Kaluski D, Halpern Z, Oren R. Prevalence of primary non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in a population-based study and its association with biochemical and anthropometric measures. Liver Int Off J Int Assoc Study Liver. 2006;26:856–63.

- Das K, Das K, Mukherjee PS, Ghosh A, Ghosh S, Mridha AR, et al. Nonobese population in a developing country has a high prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver and significant liver disease. Hepatol Baltim Md. 2010;51:1593–602.

- Wright-Pascoe R, Lindo JF. The age-prevalence profile of abdominal obesity among patients in a diabetes referral clinic in Jamaica. West Indian Med J. 1997;46:72–5.

- Patell R, Dosi R, Joshi H, Sheth S, Shah P, Jasdanwala S. Non Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) in Obesity. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:62–66

- Fabbrini E, Sullivan S, Klein S. Obesity and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Biochemical, Metabolic and Clinical Implications. Hepatol Baltim Md. 2010;51:679–89.

- Jimba S, Nakagami T, Takahashi M, Wakamatsu T, Hirota Y, Iwamoto Y, et al. Prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and its association with impaired glucose metabolism in Japanese adults. Diabet Med J Br Diabet Assoc. 2005;22:1141–5.

- 2001 National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Guidelines on the Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of Elevated Cholesterol in Adults: Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III). [Internet] National Cholesterol Education Program National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute National Institutes of Health NIH Publication No. 02-5215 September 2002. Available from https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/resources/heart/atp-3-cholesterol-full-report.pdf.

- Lavekar A, Saoji A, Jadhav S, Lavekar A, Raje D, Jibhkate S. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease prevalence and associated risk factors–A study from rural sector of Maharashtra. Trop Gastroenterol. 2015;36:25–30.