|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Original Articles |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

Acute pancreatitis, Demography, Mortality, Necrosectomy, Survival. |

|

|

|

Shrihari Anil Anikhindi, Ashish Kumar, Vikas Singla, Praveen Sharma, Naresh Bansal, Nishant Verma, Anil Arora Institute of Liver, Gastroenterology & Pancreatico-Biliary Sciences, Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, New Delhi, India.

Corresponding Author:

Dr Ashish Kumar Email: ashishk10@yahoo.com

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.555

Abstract

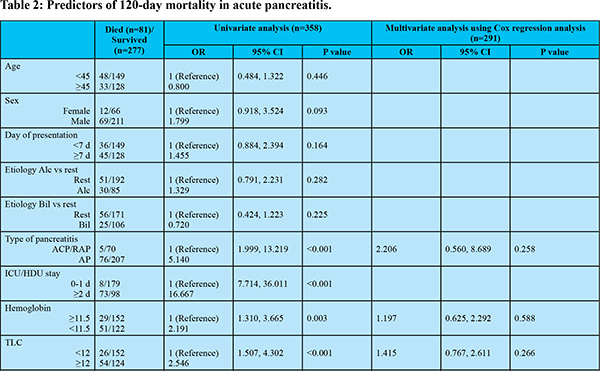

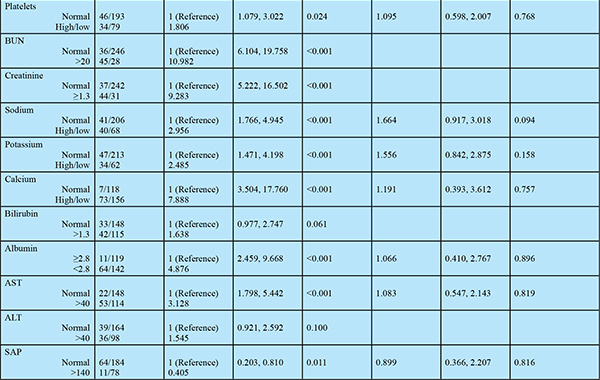

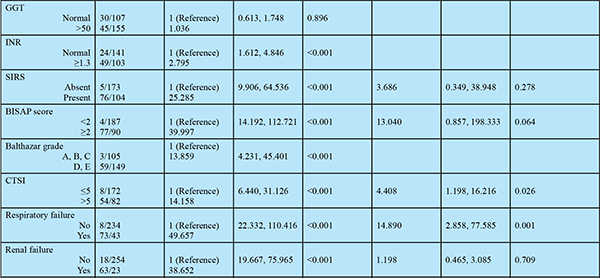

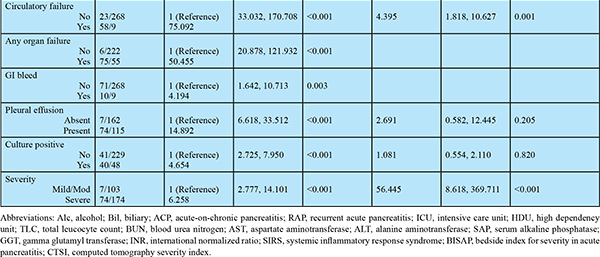

Background: Acute Pancreatitis (AP) presents with a wide range of severity and has varying outcomes. We report our experience with 358 consecutive patients with AP admitted to a tertiary care centre in North India for two years. Methods: In this retrospective study, clinical, biochemical, radiological, and treatment-related data of patients admitted with AP was collected and analysed. Predictors of 120-day mortality and treatment outcomes were analysed. Results: 358 patients (median age 42 years, 78% males) were included. The most common aetiology was biliary (37%) and alcohol (32%). Sixty-nine percent of patients had severe disease at admission according to the revised Atlanta classification. A total of 81 of 358 patients (23%) died within 120 days, with most of the deaths occurring within the first month of illness. A significant proportion of patients having severe AP (74/248, 29.8%) succumbed to illness, while only 6.4% (7/110) patients with mild or moderately severe AP had mortality within 120 days. On multivariate (Cox regression) analysis, the independent factors predicting 120-day mortality were: CT severity index >5 (OR 4.4), presence of respiratory failure (OR 14.9), presence of circulatory failure (OR 4.4), and severe pancreatitis on admission according to revised Atlanta classification (OR 56.4). Conclusions: Biliary and alcohol are the most common aetiologies of acute pancreatitis in north India. Acute pancreatitis still carries a poor outcome with a 23% mortality rate. Patients having severe pancreatitis at admission, according to revised Atlanta classification, are at the highest risk for mortality and should receive intensive care.

|

48uep6bbphidcol2|ID 48uep6bbphidvals|2940 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Introduction

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a common cause of admission in hospitals and was found to be the second most common cause for admission in Gastroenterology units.1 According to western literature, the incidence of AP is around 5-75 per 1,00,000 patients2, which by most conservative estimates seems to be lower than the actual number. This incidence has been increasing in recent years, possibly due to the obesity epidemic that is an established risk factor for gallstone disease.3 It has a wide spectrum of presentations, ranging from a mild disease that has a benign course and excellent outcome, to severe disease that inevitably needs intensive support and is frequently associated with high morbidity and mortality.4 It also incurs an excessive financial and emotional burden on the patient and the caretakers due to usually prolonged and uncertain course. We report our experience with 358 consecutive patients with AP admitted at a tertiary care centre in North India for two years.

Patients and Methods

Patients

We retrospectively analysed the clinical data from consecutive patients with AP, admitted to a tertiary care centre in India between October 2012 and October 2014. AP was diagnosed based on the most widely used definition based on 1992 Atlanta symposium5 when two of the following three criteria were present: (1) symptoms (i.e., epigastric pain) consistent with AP; (2) a serum amylase or lipase level greater than three times the laboratory’s upper limit of normal (110 U/L and 208 U/L); and (3) radiologic imaging consistent with AP, using Computed Tomography (CT) or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). Underlying chronic pancreatitis (CP) was documented if there was the presence of pancreatic atrophy, duct distortion, or strictures, calcifications established features of pancreatic exocrine dysfunction or pancreatic endocrine dysfunction.6 ‘Recurrent acute pancreatitis’ was defined by the presence of more than two attacks of AP without any underlying evidence of CP.7 The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

Baseline evaluation

Data was collected for each patient admitted with AP. This included demographic parameters like age, sex, aetiology, and AP classification, as well as various laboratory parameters, radiological imaging, clinical outcome, and mortality. Contrast-enhanced CT was done in patients with normal renal parameters after the first week of illness and subsequently in case of unexplained deterioration in the clinical course or prior to planned therapeutic interventions. Blood, urine, and pus cultures were sent in suspected sepsis cases or patients with suspected infected pancreatic necrosis (IPN). The day of presentation in this study referred to the day from the onset of symptoms to our centre’s admission.

Etiological work-up

The attack of AP was considered as related to gallstones if there was imaging evidence of cholelithiasis or choledocholithiasis on abdominal ultrasound, CT scan, MRI, or ERCP. Even in the absence of imaging evidence, the etiology was considered as biliary if there was high clinical suspicion along with the presence of abnormal liver function tests, which included alanine aminotransferase levels >100 U/L or serum bilirubin >2 mg/dl. Alcohol was considered an etiologic factor when the patient reported a regular high intake of alcohol amounting to at least more than 14 standard drinks per week. The cause was conventionally considered idiopathic when identifiable risk factors could not be found, despite comprehensive investigations and biochemical screening in these patients. Potential etiologies, such as recognized drug intake, abdominal trauma, hypertriglyceridemia, and recent ERCP, were also recorded.

Severity indices

Clinical severity indices like systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS)8 and Bedside Index for Severity in AP (BISAP)9 were documented in all patients. Radiological indices for assessing the severity of AP included Balthazar and CT severity index (CTSI) score.10 All patients were classified either into mild, moderately severe, or severe AP based on the presence and duration of organ dysfunctions as defined by the revised Atlanta classification.5

Treatment

All patients were given standard medical care, which included intravenous fluids; nasogastric or nasojejunal tube insertion for gastric decompression and enteral feeding as per requirement; analgesics for pain when needed; and antibiotics in patients with suspected or documented infections. A step-up approach with drainage followed by necrosectomy (if required) was adopted in case of lack of desired clinical benefit or deterioration (no resolution or worsening of fever, and high WBC counts, or development of new organ failure) on conservative management. Percutaneous (Ultrasound (USG)/CT guided) or Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) guided drainage of suitable pancreatic/peripancreatic collections was done in case of non-improving clinical status or deterioration. In case of persisting clinical deterioration with necrotic collections not amenable to percutaneous drainage, the patients were subjected to primary necrosectomy. During necrosectomy, the necrotic debris was removed bluntly, and the retroperitoneum was copiously irrigated. Drains were left in situ for gravitational drainage. Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20 (Chicago, IL, United States). Continuous variables were presented as median (range), and categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. The comparison of continuous variables between the groups was performed using the Mann Whitney U test. Categorical data between the groups were compared using the Chi-square test or Fischer’s exact test as appropriate. The Cox regression model was used to identify independent risk factors for mortality. For all statistical tests, a p-value <0.05 was taken to indicate significance.

Results

Patients

A total of 358 consecutive patients with AP were admitted at our centre between October 2012 and October 2014 (Table 1). The median age of the patients was 42 years (range 12-90 years), with males constituting 78%. The majority of the cases (79%) were patients with an index attack of AP, while patients presenting with repeat attacks or having pre-existing CP constituted around 12% and 9%, respectively. The median duration of illness prior to presentation at our centre was six days.

Fifty-six percent of the entire cohort required initial or subsequent admission in the intensive care unit (ICU) or high dependency unit (HDU) due to the presence of SIRS or organ failure(s). Sixty-nine percent of patients at presentation had severe disease with organ failure(s) persisting for >48 hours, while the proportion of patients with the moderately severe or mild disease was 31%. The most common organ failure was respiratory, seen almost in all patients with severe pancreatitis.

Etiological profile

The most common aetiology of AP was biliary (37%) followed closely by alcohol (32%) (Table 1). Other causes included Iatrogenic, n=8 (post-ERCP n=6, post-surgery n=2); post-traumatic, n=2; drug/viral induced, n=5; metabolic, n=4; familial, n=4; and anatomical causes (pancreas divisum), n=2. Exact aetiology could not be ascertained in 87 (24%) patients. Alcohol-related AP affected a younger population as compared to biliary AP (median age 37 vs. 52 years; p<0.01). There was also a significant difference in the gender distribution between the two groups; 37% of patients with biliary AP were females while there was no female patient with alcohol-related AP in our cohort. Other notable differences between the two groups included differences in levels of serum alkaline phosphate and international normalized ratio (INR).

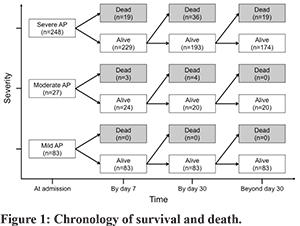

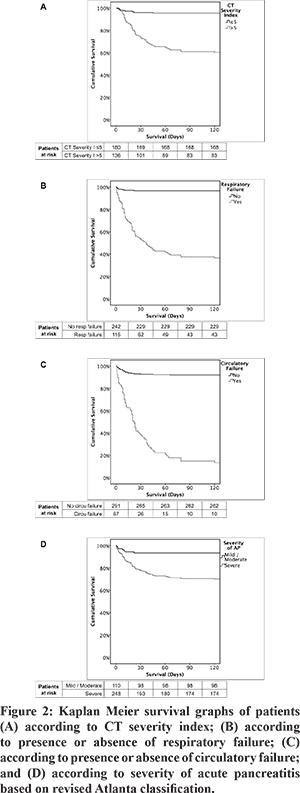

Mortality analysis

A total of 81 of 358 patients (23%) with AP died within 120 days (Table 2), with most of the deaths occurring within the first month of illness (Figure 1). A significant proportion of patients having severe AP (74/248, 29.8%) succumbed to illness, while only 6.4% (7/110) patients with mild or moderately severe AP had mortality within 120 days. On univariate analysis multiple factors were found to predict mortality, however, on multivariate analysis using Cox regression analysis, the independent factors predicting 120-day mortality were: CT severity index >5 (OR 4.4), presence of respiratory failure (OR 14.9), presence of circulatory failure (OR 4.4), and severe pancreatitis on admission according to revised Atlanta classification (OR 56.4) (Figure 2).

We analysed the time in the course of the disease, during which the deaths occurred (Figure 1). The disease course was divided into early (=7 days), intermediate (8-30 days), and late phases (>30 days). Twenty-two of the total of 81 deaths (27%) had occurred by the seventh day of admission, and by day-30, 76% (62/81) of all deaths had occurred. Among patients who had severe AP (n=248) and had died (n=74), 26% (19/74) succumbed within seven days of admission, while 48% and 26% of patients succumbed during the intermediate and late periods of illness respectively.

Sub-group analysis after excluding RAP and ACP

Since patients of RAP and ACP may have different outcomes and prognosis than patients with pure AP, a sub-group analysis was done of predictors of 120-day mortality after excluding patients with RAP and ACP (Table 3). There were 283 patients of AP, of which 76 (37%) had died within 120 days. On univariate analysis multiple factors were found to predict mortality, however, on multivariate analysis, the independent factors predicting 120-day mortality were: CT severity index >5 (OR 3.6), presence of respiratory failure (OR 11.8), presence of circulatory failure (OR 5.5), and severe pancreatitis on admission according to revised Atlanta classification (OR 50.2). Thus even after excluding patients with RAP and ACP, the factors influencing 120-day mortality remained the same.

Infection profile

The infection profile derived from culture-positive growths from blood, urine, or pus revealed a predominance of Gram-negative organisms, especially Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia Coli (Table 4). A total of 88 (24%) patients had culture-positive infections, and the organisms were isolated from blood in 51/88 (58%), pus in 44/88 (50%), and urine in 19/88 (22%). Among the Gram-positive infections, Enterococcus species was the most common organism isolated from our centre. Fungal growth predominantly consisted of Candidal species. Culture positive infection was significantly higher in patients who died in intermediate phase (22/40 (55%)) and late phase (14/19 (74%)), compared to early phase (4/22 (18%); p<0.05).

Therapeutic interventions and outcomes

Eighty patients (22%) underwent therapeutic interventions: that included either PCD and/or endoscopic drainage alone (n=49); primary necrosectomy (n=11); and drainage followed by necrosectomy (n=20) (Table 5). Sixty-nine patients were initially treated with PCD or endoscopic drainage, of these 37 improved, 12 died, while 20 underwent subsequent necrosectomy (step-up). Eleven patients were directly taken up for necrosectomy (primary necrosectomy). None of the patients with mild to moderate pancreatitis (n=110) required any therapeutic interventions, and the outcome was good, with only 7 of 110 (6.4%) patients dying. Among patients with severe pancreatitis (n=248), 80 (32%) required therapeutic intervention, and still, the outcome was poor, with 36 of 80 (45%) patients dying. The flow of patients, according to therapeutic interventions, as shown in Figure 3.

Discussion

Despite several advances, the outcomes in patients with AP are still variable, much depending on a multitude of factors in the natural course of the disease. We report our experience of a large cohort of patients with AP admitted to a tertiary referral centre in North India. The predominant aetiology of AP in our cohort was biliary (37%), followed by alcohol (32%). Most studies document these to be the two most common causes of AP, accounting for 50-70% of the total AP population. Differences in the proportion of these aetiologies may occur depending upon the region of study and referral practices.11,12 A recent study from South India had an alcohol-induced AP as the predominant cohort,13 while a study from Kashmir reported biliary Ascariasis to be the second most common aetiology of AP in that region.14 Gallstone disease is widespread in North India and was the reason for the high incidence of biliary AP in our cohort. Despite extensive evaluation, a definitive cause could not be identified in 24% of the patients, and these cases were labelled as Idiopathic pancreatitis. Biliary sludge has been shown to be the causative factor in most of the patients assumed to be of Idiopathic origin.15 In our study, the median age was 42 years, with males constituting around two-third of the total population. Patients with alcohol-related AP presented at a much younger age than patients with biliary AP (37 vs. 52 years, p<0.01). This is similar to previous observations.16 The median time at presentation to our centre was six days; more than half of the patients required initial or subsequent admission in intensive care or semi-intensive care for monitoring and treatment as they had SIRS or organ failure(s). Pancreatic injury due to any aetiology leads to a profound inflammatory state in which various neurohumoral mediators lead eventually to local tissue ischemia, microvascular thrombosis, and shock.17 It is pivotal to initiate early and aggressive fluid management; the disease outcomes depend upon the adequacy of treatment in these early ‘Golden Hours’.18 The vast number of clinically severe cases in our cohort is possibly attributable to the delay in the presentation of patients after the onset. This is a common situation faced in clinical practice. Manrai et al. reported that patients with severe AP and delayed hospitalization more often develop complications, including acute collections.19 The clinical course of acute pancreatitis can be myriad, with a wide range of presentation in terms of disease severity. Prognostication and disease outcomes drastically differ between patients with mild and severe pancreatitis. Sixty-nine percent of patients presenting to our centre were those with severe disease. Fifty percent of patients had evidence of SIRS at presentation, and around 32% of patients presented with respiratory failure as defined by the modified Marshall scoring system,5 while 24% and 19% of patients had renal and circulatory failures, respectively. Respiratory failure has also been previously reported as the most common single organ failure encountered in severe AP.11,12 Twenty-three percent of all patients with AP, which included 29.8% of patients with severe AP, succumbed to their illness within 120 days. This was much higher than previously quoted literature,20,21 and is probably due to referral bias. We found comparable mortality for patients with alcohol-related AP as compared to biliary AP. Alcohol-induced AP is considered to accrue over several years of toxin (ethanol) exposure leading to progressive subclinical injury to functional pancreatic parenchyma,22 while biliary AP is a truly an acute event. Previous studies also have reported similar outcomes.16 In our study, multivariate analysis revealed CTSI score, respiratory failure, circulatory failure, and revised Atlanta based classification to be the best independent predictors of mortality. Various studies have tried to establish the superiority of one score over the other in AP, but most have produced conflicting results.13,23-27 Many investigators have also found CTSI to have a significant correlation with clinical outcome.28-30 The revised Atlanta criteria for classifying AP into various severities based on the presence and duration of organ failures is presently the most accepted classification worldwide.31 A careful analysis of the patients who died revealed that 8% (19/248) of the patients could not survive the first week of illness, while around 14% of the patients succumbed in the intermediate stage since admission. Among the severe AP patients who died, 26% succumbed within the first week of onset of illness, while 48% and 26% of patients succumbed during the intermediate and late periods of illness, respectively. A large reported series of 643 patients with severe AP reported 42% and 58% mortality in the first two weeks and later periods of illness respectively.32 Our results with early mortality were almost similar to the above study. The percentage of early mortality from the disease varies from less than 10% to 85% between various centers.33 Early and judicious fluid management with good intensive support systems is pivotal in the early stages of the disease. Inconsistencies in this vital intervention and delay in the presentation might explain the vast difference in outcomes reported from various centres. The presence of organ failures predominates in the early stages, while sepsis is significantly more common in the later stages. This is in conjunction with the previously known concept of two peaks of mortality in AP.34 Seventy-four percent (14 of 19) of the patients with delayed mortality group had culture-positive sepsis. Septic complications in severe necrotizing AP have been previously reported to be 40-70%.35 Predominant tissue where the septic focus was confirmed included blood (in 58% of culture-positive patients), pus obtained from infected pancreatic/peripancreatic tissue (in 50%), and urine (in 22%). The organism profile revealed a predominance of Gram-negative organisms, including Klebsiella and E. Coli, whereas Enterococcus predominated among the Gram-positive infections. A similar organism profile has been reported previously from western literature.36 This points to the predominant role played by enteric microbes in causing infections in severe necrotizing AP. The significant mortality in later stages of the disease could be attributed to sepsis as well as high mortality associated with interventions undertaken in this stage of illness. Interventions in the form of drainage (percutaneous or endoscopic) or pancreatic necrosectomy were performed in 80 patients. The step-up approach for managing necrotizing AP proposed in 2010 by Santvoort et al.37 is currently the most preferred strategy for management.38 This involves performing either percutaneous or endoscopic drainage as feasible, followed by surgery if required. We observed that about 46% (37 of 80) of the patients showed good outcomes with drainage alone and did not require further surgery. It has previously been reported that PCD obviates the need for surgical intervention in infected necrotizing pancreatitis in 30 to 100 percent of cases.39 However, there is also a cohort of patients who do not have adequately localized collections amenable to drainage necessitating primary necrosectomy if clinical deterioration persists. Outcomes in these patients are especially poor; overall mortality in this group being 64%, which is much more than that of patients managed with a step-up approach. In our experience, patients who eventually required pancreatic necrosectomy due to failure of response to drainage, the outcome was much grimmer, with mortality being seen in around 85% of these patients (17 of 20). This was in contrast to the good results shown with a step-up approach in a study by Santvoort et al.37 A possible explanation could be due to delays in a necrosectomy decision, as most of these patients had already established multi-organ failures before surgical intervention. Also, most of the interventions were open pancreatic necrosectomies as less invasive newer procedures were not yet available at our centre. Less invasive procedures like video-assisted retroperitoneal debridement (VARD) and percutaneous endoscopic necrosectomy (PEN) have rightfully taken over conventional open necrosectomy. A recent article by Agarwal et al.40 has documented a significant reduction in AP mortality over the years due to improvement in management. Our study has certain limitations. First, our study population had a very high proportion of severe pancreatitis (69%). However, this is not unexpected because our centre is a tertiary care centre and a major referral centre for acute pancreatitis from entire north India. Second, being a retrospective study, the factors determining outcome in those patients who failed to respond to primary drainage could not be analysed. These could be but not limited to the extent of necrosis, early organ failure, obesity, malnutrition, and antibiotic-resistant organisms. Third, we have included patients with recurrent acute and acute on chronic pancreatitis. These patients may have a different clinical course and outcome from the usual acute pancreatitis. Many times it may be challenging to ascertain whether a patient of AP has underlying chronic pancreatitis. Since the presentation of all these patients was as ‘acute pancreatitis’, we have analysed them together. We have also done a sub-group analysis after excluding patients of RAP and ACP for factors influencing the mortality. The result of this sub-group analysis is similar to the main analysis. In conclusion, in our study, patients with AP were most commonly middle-aged persons with male predominance. Gall stone disease and alcohol constituted the majority of the causes, and most patients presented during the index event of AP. Most of the patients presented around the first week of onset illness, and almost 56% of those patients required intensive or semi-intensive care. Sixty-nine percent of patients at presentation had severe disease with organ failure(s) persisting for >48 hours, while the proportion of patients with the moderately severe or mild disease was 31%. Most commonly seen organ failure was respiratory, and multi-organ failures portended especially poor outcomes. The predominant cause for delayed mortality was Gram-negative sepsis. The independent factors predicting 120-day mortality were: CT severity index >5, presence of respiratory failure, presence of circulatory failure, and severe pancreatitis on admission according to revised Atlanta classification.

Acknowledgments

This study did not receive any funding.

References - Russo MW, Wei JT, Thiny MT, Gangarosa LM, Brown A, Ringel Y, et al. Digestive and liver diseases statistics, 2004. Gastroenterology. 2004 May;126(5):1448–53.

- Sandler RS, Everhart JE, Donowitz M, Adams E, Cronin K, Goodman C, et al. The burden of selected digestive diseases in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2002 May;122(5):1500–11.

- Koebnick C, Smith N, Black MH, Porter AH, Richie BA, Hudson S, et al. Pediatric obesity and gallstone disease: results from a cross-sectional study of over 510,000 youth. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012 Sep;55(3):328–33.

- Beger HG, Rau BM. Severe acute pancreatitis: Clinical course and management. World J Gastroenterol. 2007 Oct 14;13(38):5043–51.

- Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, et al. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013 Jan;62(1):102–11.

- Whitcomb DC, Frulloni L, Garg P, Greer JB, Schneider A, Yadav D, et al. Chronic pancreatitis: An international draft consensus proposal for a new mechanistic definition. Pancreatol Off J Int Assoc Pancreatol IAP Al. 2016 Apr;16(2):218–24.

- Kedia S, Dhingra R, Garg PK. Recurrent acute pancreatitis: an approach to diagnosis and management. Trop Gastroenterol. 2013 Sep;34(3):123–35.

- Kaukonen K-M, Bailey M, Pilcher D, Cooper DJ, Bellomo R. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria in defining severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2015 Apr 23;372(17):1629–38.

- Gao W, Yang H-X, Ma C-E. The Value of BISAP Score for Predicting Mortality and Severity in Acute Pancreatitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE [Internet]. 2015 Jun 19 [cited 2016 Apr 23];10(6). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4474919/

- Bollen TL, Singh VK, Maurer R, Repas K, van Es HW, Banks PA, et al. A comparative evaluation of radiologic and clinical scoring systems in the early prediction of severity in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012 Apr;107(4):612–9.

- Steinberg W, Tenner S. Acute pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1994 Apr 28;330(17):1198–210.

- Gullo L, Migliori M, Oláh A, Farkas G, Levy P, Arvanitakis C, et al. Acute pancreatitis in five European countries: etiology and mortality. Pancreas. 2002 Apr;24(3):223–7.

- Vengadakrishnan K, Koushik AK. A study of the clinical profile of acute pancreatitis and its correlation with severity indices. Int J Health Sci. 2015 Oct;9(4):410–7.

- Khuroo MS, Zargar SA, Yattoo GN, Koul P, Khan BA, Dar MY, et al. Ascaris-induced acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 1992 Dec;79(12):1335–8.

- Lee SP, Nicholls JF, Park HZ. Biliary sludge as a cause of acute pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1992 Feb 27;326(9):589–93.

- Zheng Y, Zhou Z, Li H, Li J, Li A, Ma B, et al. A multicenter study on etiology of acute pancreatitis in Beijing during 5 years. Pancreas. 2015 Apr;44(3):409–14.

- Aggarwal A, Manrai M, Kochhar R. Fluid resuscitation in acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 Dec 28;20(48):18092–103.

- Fisher JM, Gardner TB. The “golden hours” of management in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012 Aug;107(8):1146–50.

- Manrai M, Kochhar R, Gupta V, Yadav TD, Dhaka N, Kalra N, et al. Outcome of Acute Pancreatic and Peripancreatic Collections Occurring in Patients With Acute Pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 2016 Nov 1;

- van Dijk SM, Hallensleben NDL, van Santvoort HC, Fockens P, van Goor H, Bruno MJ, et al. Acute pancreatitis: recent advances through randomised trials. Gut. 2017 Nov;66(11):2024–32.

- Hamada S, Masamune A, Kikuta K, Hirota M, Tsuji I, Shimosegawa T, et al. Nationwide epidemiological survey of acute pancreatitis in Japan. Pancreas. 2014 Nov;43(8):1244–8.

- Dufour MC, Adamson MD. The epidemiology of alcohol-induced pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2003 Nov;27(4):286–90.

- Rathnakar SK, Vishnu VH, Muniyappa S, Prasath A. Accuracy and Predictability of PANC-3 Scoring System over APACHE II in Acute Pancreatitis: A Prospective Study. J Clin Diagn Res JCDR. 2017 Feb;11(2):PC10–3.

- Cho JH, Kim TN, Chung HH, Kim KH. Comparison of scoring systems in predicting the severity of acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol WJG. 2015 Feb 28;21(8):2387–94.

- Sharma V, Rana SS, Sharma RK, Kang M, Gupta R, Bhasin DK. A study of radiological scoring system evaluating extrapancreatic inflammation with conventional radiological and clinical scores in predicting outcomes in acute pancreatitis. Ann Gastroenterol. 2015 Sep;28(3):399–404.

- Yadav J, Yadav SK, Kumar S, Baxla RG, Sinha DK, Bodra P, et al. Predicting morbidity and mortality in acute pancreatitis in an Indian population: a comparative study of the BISAP score, Ranson’s score and CT severity index. Gastroenterol Rep. 2015 Mar 2;

- Senapati D, Debata PK, Jenasamant SS, Nayak AK, Gowda S M, Swain NN. A prospective study of the Bedside Index for Severity in Acute Pancreatitis (BISAP) score in acute pancreatitis: an Indian perspective. Pancreatol Off J Int Assoc Pancreatol IAP Al. 2014 Oct;14(5):335–9.

- Banday IA, Gattoo I, Khan AM, Javeed J, Gupta G, Latief M. Modified Computed Tomography Severity Index for Evaluation of Acute Pancreatitis and its Correlation with Clinical Outcome: A Tertiary Care Hospital Based Observational Study. J Clin Diagn Res JCDR. 2015 Aug;9(8):TC01-05.

- Sahu B, Abbey P, Anand R, Kumar A, Tomer S, Malik E. Severity assessment of acute pancreatitis using CT severity index and modified CT severity index: Correlation with clinical outcomes and severity grading as per the Revised Atlanta Classification. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2017 Jun;27(2):152–60.

- Raghuwanshi S, Gupta R, Vyas MM, Sharma R. CT Evaluation of Acute Pancreatitis and its Prognostic Correlation with CT Severity Index. J Clin Diagn Res JCDR. 2016 Jun;10(6):TC06-11.

- Sarr MG, Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, et al. The new revised classification of acute pancreatitis 2012. Surg Clin North Am. 2013 Jun;93(3):549–62.

- Fu C-Y, Yeh C-N, Hsu J-T, Jan Y-Y, Hwang T-L. Timing of mortality in severe acute pancreatitis: experience from 643 patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2007 Apr 7;13(13):1966–9.

- Werner J, Feuerbach S, Uhl W, Büchler MW. Management of acute pancreatitis: from surgery to interventional intensive care. Gut. 2005 Mar;54(3):426–36.

- Kylänpää L, Rakonczay Z, O’Reilly DA. The clinical course of acute pancreatitis and the inflammatory mediators that drive it. Int J Inflamm. 2012;2012:360685.

- Mifkovic A, Pindak D, Daniel I, Pechan J. Septic complications of acute pancreatitis. Bratisl Leka´rske Listy. 2006;107(8):296–313.

- Schmid SW, Uhl W, Friess H, Malfertheiner P, Büchler MW. The role of infection in acute pancreatitis. Gut. 1999 Aug;45(2):311–6.

- van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Bakker OJ, Hofker HS, Boermeester MA, Dejong CH, et al. A step-up approach or open necrosectomy for necrotizing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2010 Apr 22;362(16):1491–502.

- Srinivasan G, Venkatakrishnan L, Sambandam S, Singh G, Kaur M, Janarthan K, et al. Current concepts in the management of acute pancreatitis. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2016 Dec;5(4):752–8.

- Besselink MGH, van Santvoort HC, Nieuwenhuijs VB, Boermeester MA, Bollen TL, Buskens E, et al. Minimally invasive “step-up approach” versus maximal necrosectomy in patients with acute necrotising pancreatitis (PANTER trial): design and rationale of a randomised controlled multicenter trial [ISRCTN13975868]. BMC Surg. 2006;6:6.

- Agarwal S, George J, Padhan RK, Vadiraja PK, Behera S, Hasan A, et al. Reduction in mortality in severe acute pancreatitis: A time trend analysis over 16 years. Pancreatol Off J Int Assoc Pancreatol IAP Al. 2016 Apr;16(2):194–9.

|

|

|

|

|

|