48uep6bbphidcol2|ID

48uep6bbphidvals|1937

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Case Report

A 10-year-old female child was admitted with complaints of headache and lethargy for 3 days. There was no history of abnormal movement, photophobia, jaundice, ear discharge, recent travel or trauma. She was a known case of seizure disorder for the past 5 years, controlled on valproate at 12 mg/kg/day. She was off valproate for the last 1 year till 2 months back when she had a repeat seizure and was restarted on valproate at the same dose. The drug compliance was good and the medicine was administered by the child’s mother. There was no history suggestive of drug overdose. A previous magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain and electroencephalogram (EEG) were normal. The child was developmentally normal but had a poor scholastic performance.

On examination, the child was drowsy with GCS 13/15(E3V4M6) with stable vitals . Mild icterus was seen. She had no pallor, cyanosis, clubbing, lymphadenopathy and edema. Neurologic examination showed that higher mental functions, cranial nerves, motor system, sensory system, superficial and deep reflexes, pupillary reflex and fundus examination were all normal. There were no meningeal signs or Kayser-Flescher rings. Systemic examination was essentially normal except for hepatomegaly, with the liver palpable 3 cm below the costal margin. The liver was non-tender with a span of 12 cm soft. There was no free fluid in the abdomen on clinical examination.

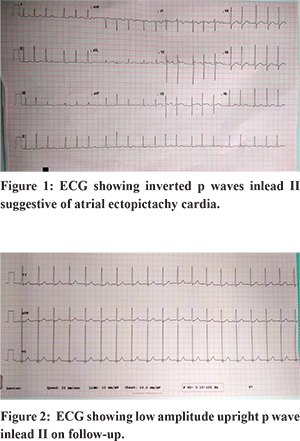

The initial laboratory investigations revealed haemoglobin of 10.8, total leukocyte count (TLC) of 4800/mm3 (differential leukocyte counts-neutrophil 47%;lymphocytes 34%; monocytes 9.8%;eosinophils 8.1%, platelets 1 lakh/mm3. Sepsis screen was negative. Thetotal serum bilirubinwas 1.3 g /dL (direct bilirubin=1.1);SGOT was 4331 U/L, SGPT was 3272 U/L, prothrombin time was 19 s, international normalized ratio (INR) was 1.7 and serum ammonia 86.3 mcg/dl. In view of transaminitis with thrombocytopenia with a negative sepsis screen, viral hepatitis work up and serum valproate levels were sent. Valproate was stopped and levetiracetam at 20 mg/kg loading followed by 10 mg/kg/day maintenance dose was started. A provisional diagnosis of fulminant hepatic failure with hepatic encephalopathy stage 1 with the etiology being either viral hepatitis or valproate toxicity was kept. The treatment regime for fulminant hepatic failure was started. A neurologist opinion was sought following which a repeat MRI brain and EEG, both of which were normal. Ultrasound abdomen showed borderline hepatomegaly with normal liver echotexture. Serum valproate levels were 106.6 mcg/ml (cut-off for toxic levels=100 mcg/ml) andIgM anti-HEV antibody was positive.On the second day of admission, the patient had three episodes of right focal seizures for which levetiracetam was increased to 30 mg/kg/day. Simultaneously, the cardiac rhythm was noticed to be irregularly irregular with a rate of 78 per minute. An electrocardiogram (ECG) (Figure 1) showed low amplitude P waves which were upright in lead V1 and inverted in lead II with variable conduction with atrial rate of 300/min, ventricular rate 94-150/min, normal QRS complex and QTc interval of 450 ms suggestive of an atrial ectopic tachycardia (AET) with variable AV conduction block (2:1/ 3:1).Cardiac enzymes (Trop T-negative, Trop-I-0.00, CKMB-1.3) were normal and electrolytes as well as thyroid function tests were normal. Echocardiogram showed mild left ventricular (LV) systolic dysfunction with left ventricular fractional shortening (LVFS) of 24% and trivial tricuspid regurgitation with no structural defects. The child remained hemodynamically stable during the episode. Serial monitoring of coagulation profile, liver function tests and electrolytes was done. A repeat ECG done before discharge showed persistent atrial tachycardia with AV block along with improving liver function tests (SGPT-486,SGOT-88.4 ). On follow up after 2 weeks, echocardiogram was normal and ECG showed regular sinus rhythm with low amplitude upright P waves in Lead II (Figure 2). Liver functions had normalized as well.

Discussion

Atrial ectopic tachycardia (AET) is uncommon, accounting for about 10% of supraventricular tachycardias (SVTs) in children.1 It is usually idiopathic but may be seen in patients with myocarditis,cardiomyopathy, severe AV valve regurgitation, atrial tumours, atrial dilatation, respiratory infections like mycoplasma pneumonia, viral infections and post cardiac surgery cases. Our case not only had AET but also had associated AV conduction block and mild left ventricular dysfunction withLVFS of 24%. LV dysfunction in our case was not due to actual persistent tachycardia as her heart rates (ventricular rates) were within physiological range due to the associated AV conduction block. This points towards the involvement of multiple sites like atria, the conduction system and ventricular myocardium in our case. A diffuse cardiac involvement such as this may be seen in cases of myocarditis due to infections and toxins. It is well known that acute myocarditis may not have an associated derangement of cardiac enzymes. Our case also had normal values of different cardiac enzymes despite clinical evidence of diffuse cardiac involvement.The diffuse cardiac involvement in our case could be due to drugs, hepatitis-related or virus-induced (hepatitis E).

Valproate (VPA) induced atrial tachycardia was considered as a possibility and literature was reviewed. Therapeutic levels of valproate are commonly described to be between 50 and 100 mcg/ml with toxic levels being more than 100 mcg/mL. VPA-induced hepatotoxicity is mainly of two types- transient dose-dependent with asymptomatic elevation of liver enzymes and rare idiosyncratic non-dose related with symptomatic hepatitis, that may be fatal. Very few cases of atrial tachycardia have been reported with valproate toxicity, but valproate levels in those cases were significantly higher(>1150 mg/l)requiring secondary detoxification by hemo-perfusion. This was unlike in our case where valproate levels were only marginally increased above therapeutic levels. Valproate toxicity is also associated with prolonged QTc interval in ECG, while in our case, the QTc was normal.Therefore AET due to valproate toxicity is unlikely in our case.

A few cases of hepatitis E with myocarditis have been reported5. Among these is a case of a 26-year-old male patient with acute viral hepatitis E who developed symptomatic myocarditis without any significant arrhythmias. Complex atrial tachycardias have also been reported with other viral infections like respiratory syncytial virus and enteroviral infections in infants.

The temporal sequence of events and the natural course of illness as discussed above made us conclude that acute Hepatitis E virus was the cause of self-limiting AET with AV conduction block with poor myocardial function in our case along with acute fulminant hepatitis. Despite our sincere efforts in searching medical literature available to us, we could not find similar cases of AET caused by hepatitis E virus. Thus, we can say that AET caused by hepatitis E virus in our case is a novel finding that has never been reported before. The question of whether valproate contributed to the existing hepatic dysfunction due to hepatitis E remains unanswered.

References

- Walsh WP, Berul CI, Triedman JK. Cardiac Arrhythmias. In: Keane JF, Lock JE, Fyler DC, editors. Nadas’ Pediatric Cardiology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia (PA): Elsevier Inc; 2006.

- Hayashi J, Kashiwagi S, Okeda T, Okamura H, Ishibashi H, Hiramatsu Y, Fujino T et al. Electrocardiographic changes related to hypersecretion of catecholamine in a patient with fulminant hepatitis. Jpn J Med. 1988; 27:187-90.

- Ursell PC, Habib A, Sharma P, Mesa-Tejada R, Lefkowitch JH, Fenoglio JJ Jr et al.Hepatitis B virus and myocarditis. Hum Pathol. 1984 May; 15(5):481-4.

- Moreshwar S Desai, Daniel J Penny.Bile acids induce arrhythmias: old metabolite, new tricks.Heart. 2013; 99: 1629–30.

- M. Premkumar, Devraja Rangegowda, Chitranshu Vashishtha et al. Acute Viral Hepatitis E Is Associated with the Development of Myocarditis. Case Reports in Hepatology. 2015 (2015), Article ID 458056, 6 pages.