|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Original Articles |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

Celiac Disease, Irritable Bowel Syndrome, ROME III Criteria, Gluten Free Diet, Functional Dyspepsia. |

|

|

|

Avinash Bhat Balekuduru1, Vinusha Reddy2, Satyaprakash Bonthala Subbaraj1, Sanjay. V. Kulkarni2 1Department of Gastroenterology, 2Department of General Medicine, Ramaiah Medical College, Bengaluru, Karnataka-54. India.

Corresponding Author:

Dr Avinash Bhat Balekuduru Email: avinashbalekuduru@gmail.com

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.516

Abstract

Aim & Objectives of the Study: There is paucity of data of prevalence of Celiac disease (CD) in South Indians. Our aim was to study the proportion of CD among patients presenting with diarrhoea dominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D). Material and Methods: From September 2013 to August 2015, 110 adult IBS –D and 100 age and sex matched controls with functional dyspepsia (FD) were recruited in the prospective cross sectional study done at Ramaiah hospitals, Bangalore. FD and IBS-D were diagnosed based on ROME III criteria. CD was diagnosed by modified ESPGAN criteria. Serum IgA anti tissue transglutaminase (Ig A anti- tTG) antibodies were measured and esophagogastroduodenoscopy with duodenal biopsies were performed in all the patients. The study was approved by the institutional ethical committee. Results: CD was diagnosed in 2 (1.8%) of 110 IBS-D and 1 (1 %) of 100 FD group. Mean age of the patients 39.4±2.6 (Range-18- 65 years). IgA anti-tTG antibodies were positive in 4 in IBS –D and 2 in control group. Duodenal biopsy showed features of CD in 3- modified marsh grading of III in 2 IBS-D and II in 1 control groups. All patients improved symptomatically on gluten free diet. Conclusions: CD in the present study was noted in 1.8% in IBS-D and 1% in FD group. Larger screening programs involving different regions are needed for estimating true CD prevalence.

|

48uep6bbphidcol2|ID 48uep6bbphidvals|1900 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Introduction

Celiac disease (CD) is a chronic small intestinal immune-mediated enteropathy, precipitated by exposure to dietary gluten in genetically susceptible individuals. The spectrum of manifestations of CD is wide and ranges between classic CD having typical signs and/or symptoms of malabsorption (such as diarrhoea, weight loss, vitamin deficiencies, or malnutrition) and non-classic CD having non-GI symptoms such as short stature, anaemia, infertility, or osteopenia/osteoporosis1-6. The revised European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) guidelines underscore the importance of serological testing and suggest that duodenal biopsy may be optional in selected cases, where the serological titres are more than 10 times the upper limit of normal7. Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) presents with abdominal pain or discomfort with a change in bowel habits often associated with bloating. A meta-analysis including 81 studies and 260,960 subjects, showed that the pooled prevalence of IBS was 11.2% (95% confidence interval, 9.8%-12.8%)8. The prevalence of IBS in Asian countries varies from 6.5% to 11.1%.9 Two population-based studies from India have estimated that approximately 4% of Indians have IBS10,11. Gastrointestinal diseases such as giardiasis, lactose intolerance, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and celiac disease produce symptoms mimicking those of IBS and they may easily be misdiagnosed as IBS12. There are studies which have shown 4 fold increased detection of CD in subjects who fit with criteria of IBS when compared to controls13,14. Though American Gastroenterological Association and American college of gastroenterology advocate limited or no laboratory studies in patients with symptoms of IBS, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines in the United Kingdom routinely recommend to exclude CD in all patients with IBS like symptoms15-18. British Society of Gastroenterology advocates that IBS patients should perform full blood count test plus erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein coupled with thyroid function7. In a study from India including 362 patients with IBS, only 3 (0.8%) patients had biopsy confirmed CD, which was comparable to the prevalence of CD in the general population19. The largest population based study from north India which showed prevalence of one in 310 20 but data of celiac disease in IBS of South -India are limited. The aim was to study the proportion of CD among patients with diarrhoea dominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D) and their response to gluten free diet based on the diagnosis.

Materials and Methods

A two year prospective cross-sectional study was undertaken from September 2013 to August 2015 after obtaining ethical committee clearance from the institutional body. All consecutive patients more than 18 years of age with IBS-D and functional dyspepsia (FD) who fulfil Rome III criteria referred to the Gastroenterology services of Ramaiah Hospital, Bangalore, Karnataka were included in study group. 100 age and sex-matched controls with FD undergoing endoscopy for evaluation of dyspepsia at our centre were recruited as controls in this study. An informed consent was taken from all patients. A detailed history and clinical examination was performed for all patients and entered in a structured proforma.

ROME III Criteria for Diagnosis of IBS and FD1,22

For IBS: Criteria should be fulfilled for the last 3 months from onset of symptoms and at least 6 months before diagnosis. Recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort (uncomfortable sensation not described as pain) at least 3 days per month in the last 3 months that is associated with two or more of the following: (i) Improvement with defecation. (ii) Onset associated with a change in frequency of stool. (iii) Onset associated with a change in form (appearance) of stool (Bristol stool form 6 and 7) For FD: Functional Dyspepsia was defined as uninvestigated dyspepsia without findings of esophagitis, peptic ulcer, cancer and no evidence of other structural disease at endoscopy that will likely to explain the symptoms. The diagnosis of celiac disease was established by modified ESPGAN criteria, which requires the presence of duodenal mucosal biopsy changes (Marsh II or III abnormality) and clinical response to gluten-free diet (GFD)23. Patients who were excluded: IBS-D patients on follow up and any other form of IBS, patients on NSAIDs/ antibiotics or suffered from intestinal tuberculosis or antibiotic-associated diarrhea 4 weeks prior to the study or with villous adenomas, microscopic colitis, or inflammatory bowel disease; had a history of gastro intestinal cancer or positive for antibody to human immunodeficiency virus or hepatitis C virus, hepatitis B antigen. All study patients underwent IgA Anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies (IgA anti-tTG) and Endoscopy and duodenal biopsy. Serological tests for CD were done using enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) kits (AESKULISA, Germany) for IgA tTG. Value of more than 10?IU/ml was considered as a positive test for IgA anti-tTG, as per the manufacturers’ guidelines. Duodenal biopsy was obtained from the second/ third part of the duodenum (4-6 pieces) and sent for histopathological examination in formalin bottle. The slides were stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E), reported independently by a trained histopathologist and was graded using the modified Marsh classification24,25. The patients were followed up at regular intervals, for 1 year on departmental outpatient basis.

Statistical Software

The baseline characteristics were expressed as the mean with standard deviation for continuous data. Frequency differences were compared using Fisher exact test. Statistical significance was established at the P value<0.05. All calculations were performed using SPSS for Windows, version 18.0 (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL) and MedCalc 9.0.1.

Results

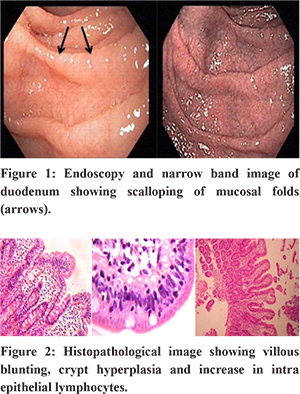

During the study period, 110 patients (40 females and 70 males) and 100 FD controls (35 females and 65 males) comprised the study group. The mean age of presentation was 39.1 ±2.4years. The most common age group affected was 31-40 years. The mean duration of symptoms was 26.4±8.3 (Range: 4- 180 months). Elevated IgA anti tTG antibody values of >10 U/ml (positive) were noted in 6 patients. Comparision of Ig A anti tTG antibody showed statistical differences between the IBS-D group and the FD control group (9.2+ 1.8 vs. 5.2 + 2.1, P < 0.05) Duodenum on upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was normal in 180 patients. Thirty patients had scalloping of duodenal folds (Figure1). All 210 patients had duodenal biopsy. Nonspecific duodenitis was noted in 40, 3 had celiac disease -Marsh II-1& Marsh III-2 (Figure 2) and the rest 167 had normal duodenal mucosa.

The characteristics of the 3 patients with celiac disease who were detected on duodenal biopsy and the relation of duodenal biopsy to serology were described in Table1 and table 2 respectively. The Pearson Chi square test “p” value was 0.618 between the IBS-D and FD groups. All patients with diagnosed CD or positive IgA anti tTG antibody were advised GFD and were kept on follow up and patients with IBS were managed conservatively according to their symptomology. The mean (range) duration of follow up was 13 months (4 - 26 months). All patients with celiac disease improved clinically on GFD.

Discussion

The prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome among the global population is 15-25%. On the other hand, the prevalence of CD is put at 0.5-1%26,27. IBS is more prevalent in women28 but in our study men were more than women which may be due to referral pattern. Conservative treatment with benign course is the rule in IBS. In case of CD if treated with GFD ,clinical improvement would be noted in most of the individuals. The prevalence of CD in general population and in IBS was similar to that reported in earlier studies 1 % and 1.8% respectively10. Overt CD presenting with malabsorption is easy to diagnose but early CD with minimal symptoms/ IBS like symptoms needs to be excluded before labelling as IBS. The difference between CD in FD and IBS-D is 1 and 1.8% which is a small difference. This is due to the rare occurrence of the disease and larger data might be required to show a significant difference. Diet triggers both CD and IBS-D as gluten allergy for CD while in the case of IBS-D the effect can emanate from long sugar polymer fructose found in the wheat29. Previous studies have shown that IBS-like symptoms could be seen in patients with CD and the prevalence of CD in patients with IBS is higher than that of the general population30-35. IgA antitTG anti body with a cut off value of 20 U/mL has high sensitivity of 96.8% and a specificity of 100.0%36. A lower cut off value of 10 U/mL was chosen for the study as suggested by manufacturer and the total amount of wheat in South Indian diet is much less than that North India. Three cases 2 in control and 1 in IBS-D group had positive antibody but negative for CD on biopsy. All 3 had duodenal biopsy suggestive of non-specific duodenitis but improved on GFD on follow up. They might have had non celiac gluten sensitivity37 or can be potential celiac patients38 at follow up. Among 3 CD patients, 2 had iron deficiency anaemia and one had vitamin B12 deficiency anaemia which got corrected with supplementation along with GFD. The only marker that could help in the early identification of the potential celiac patients at a higher risk to develop intestinal damage seems to be the presence of anti-TG2 IgA intestinal deposits, at the time of the initial biopsy38. The limitations of our study are manifold. Besides having a small sample size, the follow-up period in our study is only 12 months. Most other studies pertaining to this issue have been of >2 years duration. Additionally, we did not perform tissue testing for TG2 antibodies which are not available in India and genetic tests. The decrease in IgA Anti tTG antibody titres were also not checked at follow up. The present study confirms that CD exists in patients with IBS and FD subjects in South India. The traditional rice staple food gradually being replaced by Western-style food containing a high content of wheat and CD appears to inevitably become a health problem in predisposed subjects.

Conclusions

CD in the present study was noted in 1.8% in IBS-D and 1% in FD group. Larger screening in different regions is needed for CD prevalence. The presence of anaemia can help in predicting CD in IBS-D.

References - Ludvigsson JF, Leffler DA, Bai JC, et al. The Oslo definitions for celiac disease and related terms. Gut 2013; 62: 43–45. [PMC free article][PubMed]

- Mohindra S, Yachha SK, Srivastava A, et al. Coeliac disease in Indian children: assessment of clinical, nutritional and pathologic characteristics’ Health PopulNutr. 2001; 19:204–208.

- Sharma A, Poddar U, Yachha SK. Time to recognize atypical celiac disease in Indian children.Indian J Gastroenterol. 2007; 26:269–273.

- Makharia GK, Baba CS, Khadgawat R, et al. Celiac disease: variations of presentations in adults. Indian J Gastroenterol.2007; 26:162–166.

- Agarwal N, Puri AS, Grover R. Non-diarrheal celiac disease: a report of 31 cases from northern India. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2007; 26:122–126.

- Lurz E, Scheidegger U, Spalinger J et.al., Clinical presentation of celiac disease and the diagnostic accuracy of serologic markers in children. Eur J Pediatr. 2009 Jul; 168(7):839-45.

- Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szabó IR, Mearin ML, Phillips A, Shamir R, Troncone R, Giersiepen K, Branski D, Catassi C, Lelgeman M, Mäki M, Ribes-Koninckx C, Ventura A, Zimmer KP, ESPGHAN Working Group on Coeliac Disease Diagnosis., ESPGHAN Gastroenterology Committee., European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition guidelines for the diagnosis of coeliac disease. J PediatrGastroenterolNutr. 2012 Jan; 54(1):136-60. [PubMed] [Ref list]

- Lovell R.M., Ford A.C. Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: A meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012; 10:712–721. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.02.029. [PubMed][Cross Ref]

- Chang F.Y., Lu C.L., Chen T.S. The current prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in Asia. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2010; 16:389–400. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2010.16.4.389. [PMC free article][PubMed][Cross Ref]

- Makharia G.K., Verma A.K., Amarchand R., Goswami A., Singh P., Agnihotri A., Suhail F., Krishnan A. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome: A community based study from northern India. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2011; 17:82–87. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2011.17.1.82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Ghoshal U.C., Abraham P., Bhatt C., Choudhuri G., Bhatia S.J., Shenoy K.T., Banka N.H., Bose K., Bohidar N.P., Chakravartty K., et al. Epidemiological and clinical profile of irritable bowel syndrome in India: Report of the Indian Society of Gastroenterology Task Force. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 2008; 27:22–28. [PubMed]

- Makharia A, Catassi C, Makharia GK. The Overlap between Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity: A Clinical Dilemma. Nutrients. 2015; 7(12):10417-10426. doi:10.3390/nu7125541.

- Ford AC, Chey WD, Talley NJ, et al. Yield of diagnostic tests for celiac disease in individuals with symptoms suggestive of irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Int Med 2009; 169:651–658.

- Cash BD, Schoenfeld PS, Chey WD. The utility of diagnostic tests in irritable bowel syndrome patients: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97:2812–289.

- Drossman DA, Camilleri M, Mayer EA, Whitehead WE. AGA technical review on irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002; 123(6):2108- 2131.

- Spiller R, Aziz Q, Creed FEA, et al; Clinical Services Committee of the British Society of Gastroenterology. Guidelines on the irritable bowel syndrome: mechanisms and practical management. Gut. 2007; 56(12):1770-98.

- American College of Gastroenterology Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders Task Force. Evidence based position statement on the management of irritable bowel syndrome in North America. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002; 97(11) (suppl):S2-S5.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Irritable bowel syndrome in adults: diagnosis and management of irritable bowel syndrome in primary care. http://www.nice.org.uk /nicemedia/pdf/CG061NICEGuideline.pdf. (2008).

- Sharma H, Verma AK, Das P, Dattagupta S, Ahuja V, Makharia GK. Prevalence of celiac disease in Indian patients with irritable bowel syndrome and uninvestigated dyspepsia. J Dig Dis. 2015; 16(8):443-8.

- Sood A, Midha V, Sood N, Avasthi G, SehgalA.Prevalence of celiac disease among school children in Punjab, North India. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006; 21(10):1622-5.

- Drossman DA, Dumitrascu DL. Rome III: New standard for functional gastrointestinal disorders. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2006 Sep; 15(3):237-41.

- ROME 3: Longstreth G.F., Thompson W.G., Chey W.D., Houghton L.A., Mearin F., Spiller R.C. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006; 130(5):1480–1491. [PubMed] [Ref list]

- Walker-Smith J. Revised criteria for diagnosis of coeliac disease. Report of Working Group of European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition.Arch Dis Child. 1990; 65:909–911.

- Marsh MN, Crowe PT. Morphology of the mucosal lesion in gluten sensitivity. BaillieresClinGastroenterol. 1995 Jun; 9(2):273-93. [PubMed] [Ref list]

- Oberhuber G, Granditsch G, Vogelsang H. The histopathology of coeliac disease: time for a standardized report scheme for pathologists. Eur J GastroenterolHepatol. 1999; 11:1185–94.

- Lohi S., Mustalahti K., Kaukinen K., Laurila K., Collin P., Rissanen H. Increasing prevalence of coeliac disease over time. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007; 26:1217–25. [PubMed]

- White L.E., Merrick V.M., Bannerman E., Russell R.K., Basude D., Henderson P., Wilson D.C., Gillett P.M. The rising incidence of celiac disease in Scotland. Pediatrics. 2013 Oct; 132(4):e924-31:0932. [PubMed]

- RokSeonChoung, G. Richard Locke III . Epidemiology of IBS. GastroenterolClin N Am 2011; 40: 1–10.

- Heizer W.D., Southern S., McGovern S. The role of diet in symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome in adults: a narrative review. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2009;109:1204–14. [PubMed] [Ref list]

- Sanders DS, Patel D, Stephenson TJ, et al. A primary care cross-sectional study of undiagnosed adult coeliac disease. Eur J GastroenterolHepatol 2003; 15: 407–13.

- Catassi C, Kryszak D, Louis-Jacques O, et al. Detection of celiac disease in primary care: a multicenter case-finding study in North America. Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102(7):1454–60.

- O’Leary C, Wieneke P, Buckley S, et al. Celiac disease and irritable bowel-type symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97(6):1463–7.

- Shahbazkhani B, Forootan M, Merat S, et al. Coeliac disease presenting with symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacolther 2003; 18: 231–5.

- Korkut E, Bektas M, Oztas E, et al. The prevalence of celiac disease in patients fulfilling Rome III criteria for irritable bowel syndrome.Eur J Intern Med 2010; 21(5):389–92.

- Van der Wouden EJ, Nelis GF, Vecht J. Screening for coeliac disease in patients fulfilling the Rome II criteria for irritable bowel syndrome in a secondary care hospital in The Netherlands: a prospective observational study. Gut 2007; 56(3):444–5.

- Sugai E, Moreno ML, Hwang HJ, et al. Celiac disease serology in patients with different pretest probabilities: is biopsy avoidable? World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:3144–52.

- Volta U, Tovoli F, Cicola R, Parisi C, Fabbri A, Piscaglia M, Fiorini E, Caio G. Serological tests in gluten sensitivity (nonceliac gluten intolerance) J ClinGastroenterol. 2012;46:680–685. [PubMed]

- Tosco A, Salvati VM, Auricchio R, Maglio M, Borrelli M, Coruzzo A, Paparo F, Boffardi M, Esposito A, D’Adamo G, Malamisura B, Greco L, Troncone R. Natural history of potential celiac disease in children. ClinGastroenterolHepatol. 2011 Apr; 9(4):320-5.

|

|

|

|

|

|