48uep6bbphidcol2|ID

48uep6bbphidvals|1815

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Angioedema is a non-inflammatory disease which is characterized by episodes of increased capillary permeability with resultant extravasation of intravascular fluid and subsequent edema of the skin or mucosa of the upper airways or gastrointestinal tract. It can affect the small or large intestine and is often misdiagnosed for other gastrointestinal conditions. Though here ditary angioedema or angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor induced intestinal angioedema have been reported frequently, idiopathic intestinal angioedema or intestinal angioedema secondary to an allergic reaction have been not been reported as widely. We report an interesting case of idiopathic intestinal angioedema with migratory lesions involving the small bowel at different points of time during a single hospital admission.

Case Report

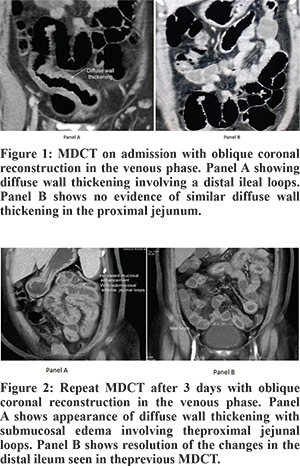

A 49 year old house-wife with no known co-morbidities presented with loose stools (6 to 8 episodes per day) for 2 days associated with severe crampy abdominal pain, discomfort and low-grade intermittent fever. She also complained of itchiness and redness over both her lower limbs for one week. Her past history included tubal ligation, laparoscopic appendicectomy, total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salphingo-oophorectomy and lateral anal sphincterotomy. There was no history of any drug intake in the months prior to presentation. General examination revealed multiple papular rashes on bilateral lower limbs. Abdominal examination revealed tenderness in right iliac fossa but no guarding or organomegaly. Blood investigations were normal except for a raised total white cell count of 18000/mm3. Chest X-ray and ECG were normal. Ultrasound scan showed fatty liver with minimal free fluid in the pelvis. She underwent contrast enhanced Multi Detector Computed Tomography (MDCT) which revealed diffuse wall thickening involving distal ileal loops with surrounding minimal free fluid and fat stranding (Figure 1). A diagnosis of ileitis, possibly of infective etiology was considered. She was kept nil by mouth for a day and was started on injection cefoperazone and analgesic (paracetamol) and intravenous fluids. Her pain settled gradually. On day 3 of admission, she was started on a liquid diet. However, she developed multiple episodes of bilious vomiting associated with severe abdominal pain in the peri-umbilical region without any fever. Abdomen was tender in umbilical and left hypochondriac regions. In view of progressive symptoms, she underwent a repeat MDCT on day 4 which showed appearance of new wall thickening with increased mucosal enhancement and submucosal edema diffusely involving the proximal jejunal loops (Figure 2A). However, the changes in the distal ileal loops seen on the earlier MDCT had completely resolved (Figure 2B). In view of the MDCT finding and the self resolving nature of the disease, a provisional diagnosis of intestinal angioedema was made. She was seen by a dermatologist who advised skin biopsy with immunofluoroscence study and autoimmune markers. The results were negative. Her serum C4 level was within normal range, C1 esterase inhibitor level was 34 mg/dl (normal 15-35) and serum IgE (Total) level was 49.2 IU/ml (normal <150). The patient was started on intravenous hydrocortisone along with empirical antibiotic therapy. There was dramatic improvement in her symptoms within 24 hours. She was started on a liquid diet on day 5 which she tolerated well and was given a normal diet on day 6. She was discharged on day 7 on oral prednisolone with tapering of the dose. She was asymptomatic at follow up in two months.

Discussion

Abdominal pain is one of the most common conditions in clinical practice, and yet it is challenging to come to an accurate diagnosis due to the vast number of possible etiologies. Intestinal angioedema is a rare condition which may be missed easily if not looked for. Most reported cases of intestinal angioedema are attributed to drug-related angioedema, often seen with the use of ACE inhibitors. Patients with hereditary angioedema may also be prone to intestinal angioedema which is due to C1-inhibitor (C1 – INH) deficiency. This enzymeis responsible for inhibiting the activity of complement. In our case, both were ruled out as patient never ingested ACE inhibitors and biochemical tests did not support the diagnosis of hereditary angioedema.

The abdominal pain of intestinal angioedema is described as cramping or colicky and is rated as severe to excruciating in 87% of patients.1 Vomiting and diarrhoea occur in 78% and 65%, respectively, of patients with abdominal symptoms.1 Though our case also presented with crampy abdominal pain, the most significant characteristics were change in location of the pain and change in the site of involvement, both of which were confirmed radiologically. Hereditary angioedema occurs due to the loss of inhibitory control of the contact/fibrinolytic pathway and the classical complement pathway caused by low levels or subnormal activity of C1 INH.2 In intestinal angioedema, the vessels of the submucosa become leaky. This allows intravascular fluid to empty into the interstitium of the submucosal lining causing edema of the intestinal walls. Mechanisms involved in cases of idiopathic or allergic intestinal angioedema are not clear.

Management of intestinal angioedema may be a challenge due to its rarity and the broad differentials associated with its presentation. Unrecognized and untreated cases of angioedema exacerbations as a whole, carry a mortality rate of 30-56%.3,4 Cases related specifically to ACE-inhibitor associated angioedema are primarily treated through recognition and discontinuation of the offending agent. Though serine proteinase inhibitors (serpins), kallikrein inhibitors and anabolic steroids have been successfully used to accelerate resolution of attacks, their efficacy have not been tested in clinical trials.5

Our case is a rare example of intestinal angioedema of unknown etiology which showed radiological findings consistent with angioedema and responded to steroid therapy. The spontaneous resolution in the ileum and reappearance in the jejunum a few days later is a new finding.

References

- Bork K, Staubach P, Eckardt AJ, Hardt J. Symptoms, course, and complications ofabdominal attacks in hereditary angioedema due to C1 inhibitor deficiency. Am JGastroenterol. 2006;101:619–627.

- Nzeako UC. Diagnosis and management of angioedema with abdominal involvement:a gastroenterology perspective. World J Gastroenterol. 2010 Oct 21;16(39):4913-21.

- Burghardt W, Wernze H. Abdominal sonography in hereditary angioneurotic edema. Acontribution to the early diagnosis of a disease of interdisciplinary significance. UltraschallMed. 1987;8:278–82.

- Cicardi M, Bergamaschini L, Marasini B, Boccassini G, Tucci A, Agostoni A.Hereditary angioedema: an appraisal of 104 cases. Am J Med Sci. 1982;284:2–9. 5.Zingale LC, Zanichelli A, Deliliers DL, Rondonotti E, De Franchis R, Cicardi M.Successful resolution of bowel obstruction in a patient with hereditary angioedema. Eur JGastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:583–7.