|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Original Articles |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

Chronic pancreatitis; pancreatic cancer; idiopathic pancreatitis; tropical chronic pancreatitis. |

|

|

|

Gopalakrishna Rajesh, Banavara Narasimhamurthy Girish, Suprabha Panicker, Rama P. Venu, Vallath Balakrishnan Department of Gastroenterology, Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences, AIMS Ponekkara P.O. Cochin - 682 041, Kerala, India.

Corresponding Author:

G. Rajesh Email: grajesh22@gmail.com

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.352

Abstract

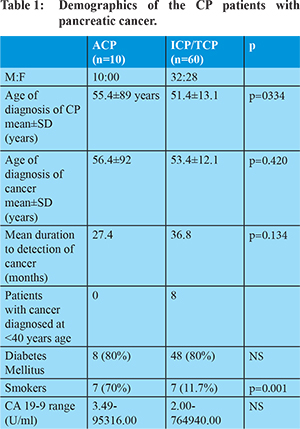

Background: Chronic pancreatitis (CP) especially tropical pancreatitis has been reported to be a pre-malignant condition. Recent reports indicate change in profile of CP in India with identification of novel risk factors; and delayed presentation as well as delayed onset of exocrine and endocrine insufficiency. The prevalence and characteristics of pancreatic cancer in the present setting is unknown. Methods: We studied the prevalence and profile of pancreatic cancer among CP patients and associated risk factors. Results: Among 1157 patients with CP enrolled and followed up prospectively in our Pancreas clinic, there were 70 (42 males, 28 females) patients who developed pancreatic cancer. Sixty (85.7%) had idiopathic/tropical chronic pancreatitis (ICP/TCP) while 10(14.3%) had alcoholic chronic pancreatitis (ACP) as underlying etiology. The mean duration to detection of cancer after diagnosis of CP was 27.4 months in ACP as compared to 36.8 months in TCP patients (p=0.134). There were only 8 patients who developed pancreatic cancer before 40 years age. Fourteen (20%) were smokers while 56 (80%) were diabetic. The tumor was located most commonly in head of pancreas in both ACP and TCP patients; however location in body and tail was less common in ACP patients. Conclusion: The prevalence of pancreatic cancer among CP was found to be 6.05% and it was far more common in ICP/TCP as compared to ACP. Onset of pancreatic cancer in young patients with CP appears to be uncommon in ICP/TCP in the present series. Diabetes mellitus and smoking were risk factors associated with pancreatic cancer.

|

48uep6bbphidcol2|ID 48uep6bbphidvals|1733 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Introduction

The association between chronic pancreatitis (CP) and pancreatic cancer is well known. A large, multicentre, historical study, reported by Lowenfels et al, estimated the risk as 1.8% and 4% at 10 and 20 years respectively in a population where alcoholic chronic pancreatitis (ACP) was the dominant etiology. 1 Previous reports form India indicated that patients with tropical pancreatitis (TCP) appeared to have an increased risk of pancreatic cancer as compared to ACP. 2-4 In a study by Augustine P and Ramesh H (1992), it was seen that pancreatic adenocarcinoma occurred in 22 of 266 patients (8.3%) with tropical pancreatitis, suggesting that TCP was especially premalignant. 3 The more recent nationwide study from India however found only 4% incidence of pancreatic cancer in a cohort of over 1000 patients. 5 In this study, classical TCP was seen in less than 4% patients. There are multiple risk factors for development of pancreatic cancer in CP. In ACP, it is likely that in addition to alcohol consumption, smoking, and possibly some dietary and environmental factors are implicated in the pathogenesis of cancer. Pancreatic cancer has been reported to occur at a younger age in TCP. The risk factors in TCP are not clear but may relate to genetic factors in view of the high frequency of familial aggregation noted in TCP, especially in South India, in addition to the putative environmental factors. The recent literature indicates a change in profile of CP in India 6-9 with identification of novel risk factors, especially genetic factors 10, and delayed presentation as well as delayed onset of exocrine and endocrine insufficiency. The prevalence and characteristics of pancreatic cancer in the present setting is unknown. We studied the prevalence and profile of pancreatic cancer among CP patients and associated risk factors.

Materials and Methods

CP patients who were enrolled and prospectively followed up in our Pancreas clinic between 2004 and 2014 were included in this study. CP was diagnosed based on the presence of typical imaging features of pancreatic calcification and/or duct dilatation with parenchymal atrophy on USG abdomen/CT scan/ERCP/MRCP/EUS studies. Patients who had consumed alcohol of at least 80g/day for 5 or more years were considered to have ACP. Patients who did not have any specific etiology for CP were considered to have idiopathic chronic pancreatitis (ICP). A multiphase MDCT scan of the abdomen using pancreas protocol was reported by a radiologist. This description was used to assign the location. Pancreatic cancer was diagnosed based on histopathological examination of resection specimens in those who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy. Percutaneous biopsy or EUS guided FNA from the pancreatic mass was the usual method for confirmation in those who were not operable. In some cases, FNA or biopsy from liver metastases was the method of diagnosis. Histology was reported by an experienced GI pathologist who also reviewed slides reported by other pathologists. All slides were reviewed once again for the study. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee, and written informed consent was obtained from the study subjects. Statistical analysis was done by using SPSS version 11 software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, USA). Data were reported as mean ± SD and frequencies. The nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test or Wilcoxon’s test was used to compare variables without a normal distribution. All tests were two-tailed and P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Among 1157 patients with CP (410 ACP, 747 TCP) enrolled and followed up prospectively in our Pancreas clinic, there were 70 (42 males, 28 females) patients who developed pancreatic cancer. Sixty (85.7%) had idiopathic/tropical chronic pancreatitis (ICP/TCP) while 10(14.3%) had alcoholic chronic pancreatitis (ACP) as underlying etiology. 54 of the 70 patients had calcific pancreatitis with large dense intraductal calculi seen in all patients with TCP/ICP. The mean age of diagnosis of ACP was 55.4±8.9 years as compared to 51.4±13.1 years in TCP patients (p=0.3). The mean age of diagnosis of pancreatic cancer in ACP was 56.4±9.2 years as compared to 53.4±12.1 years in ICP/TCP patients (p=0.4). The mean duration till development of cancer after diagnosis of CP was 27.4 months in ACP as compared to 36.8 months in TCP patients (p=0.1). There were 8 (80%) ACP as compared to 32 (53.3%) TCP patients who had a concurrent diagnosis of pancreatic cancer and chronic pancreatitis (p=0.07). All these patients had calcification and significant radiological features of CP. Presence of duct dilatation alone, was not used to diagnose underlying CP in these patients. There were only 8 patients who developed pancreatic cancer before 40 years of age. 3 (37.5%) of the 8 patients had a concurrent diagnosis of pancreatic cancer and CP. Fourteen (20%) patients were smokers while 56 (80%) were diabetic.

The tumor was located most commonly in the head of pancreas in 5 (50%) ACP as compared to 25 (41.7%) TCP/ICP patients. Location in body and tail of pancreas was uncommon in ACP as compared to TCP patients. The cumulative risk of pancreatic cancer among CP was found to be 6.05% and it was far more common in ICP/TCP as compared to ACP. None of these patients needed a subsequent revision of diagnosis as inflammatory mass. Among ACP patients, the usual symptoms at presentation were jaundice in 5 (50%), pain in 7 (70%), weight loss in 8 (80%) patients. Among TCP patients, the usual symptoms were jaundice in 20 (33.3%), pain in 22 (70%), weight loss in 38 (63.3%), and steatorrhea in 4 (6.6%) patients. There were 2 patients who had hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positivity; and 1 patient had positive antibody to hepatitis C (anti HCV). Fourteen (20%) were smokers (7 each in ACP and TCP). Fifty-six (80%) of the 70 patients were diabetic. The prevalence of diabetes was similar (80%) in both ACP and TCP patients. Pancreaticoduodenectomy was possible in 1 (10%) ACP as compared to 15 (25%) TCP patients. Interestingly, 11 of 40 patients (27.5%) with a concurrent diagnosis of CP and pancreatic cancer were resectable as compared to 5 of 30 patients (16.6%) who did not have a concurrent diagnosis.

Discussion

Previous reports suggested a higher frequency of pancreatic cancer in TCP patients at earlier ages. In this study, we found that occurrence of pancreatic cancer at a younger age is not as frequent as reported earlier even in ICP/TCP patients. The overall prevalence was <7%. This seems to be consistent with recent reports which indicate a change in the profile of TCP with delayed onset of disease, delayed presentation as well as delayed onset of exocrine and endocrine insufficiency. 6-9 The reasons for lower prevalence of cancer in the present series and the delayed presentation may be partly related to alterations in risk factors in the present setting. Our study corroborates previous reports which suggest that smoking and diabetes mellitus are risk factors for pancreatic cancer in CP. Smoking, alcohol consumption, glycemic control and obesity are obvious modifiable risk factors which need to be targeted in interventions for CP patients. Carcinogenesis in CP is likely to be multi-factorial. Chronic inflammation promotes metaplasia and neoplastic transformation in CP. Nitric oxide, free radicals, and cyclooxygenase-2 are some of the mediators involved in pancreatic carcinogenesis. Multiple attacks of pancreatitis are probably implicated in development of pancreatic cancer. An increased risk and shorter duration to development of pancreatic cancer has been traditionally described in hereditary pancreatitis and tropical pancreatitis due to the earlier onset of disease. We observed that in 40 patients, the diagnosis of CP and pancreatic cancer was concurrent as CP had not been diagnosed before detection of cancer. The dichotomy of patients who present with pancreatic cancer but have underlying CP, and patients who develop cancer after a long duration of symptomatic CP, offers avenues for investigation of risk factors. The reasons why these two groups of patients behave differently needs closer scrutiny. Smoking is probably the most well documented environmental risk factor. In multiple cohort and case-control studies, the relative risk for developing pancreatic cancer among smokers was at least 1.5 and the risk was directly correlated with the number of cigarettes consumed. 11 Protective effect from the consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables are reported. 12 Various constituents of vegetables have been proposed to have anticancer effects like dietary fibre, isothiocyanates in cruciferous vegetables and lutein, an antioxidant present in green leafy vegetables. Low levels of lycopene and selenium have been observed in persons who developed pancreatic cancer. 13 Various dietary factors have been studied but none proven conclusively to be an independent risk factor. Consumption of high fat especially saturated fat and fat from animal sources have been variably associated with development of pancreatic cancer. 14 Increased intake of carbohydrates and foods with a high glycemic index has been considered to increase risk for cancer but the relation is still unclear. Glycemia related dietary factors, insulin resistance, glucose intolerance, diabetes mellitus, insulin/insulin like growth factors, and obesity may be interlinked in etiopathogenesis of pancreatic cancer. Numerous epidemiologic studies describe an association between diabetes mellitus and pancreatic cancer. In a meta-analysis of 88 studies (50 cohort and 30 case-control, predominantly of patients with type 2 diabetes) the pooled relative risk (RR) for pancreatic cancer in diabetics compared with patients without diabetes was 2.08 (95% CI 1.87-2.32).15 The increased risk of pancreatic cancer in patients with diabetes mellitus and/or insulin resistance as well as obesity may be mediated by reduced levels of plasma adiponectin which has insulin-sensitizing and anti-inflammatory properties. Screening for pancreatic cancer in CP patients with new onset diabetes or unexplained variation in glycemic control may be beneficial for early diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. Alternatively, it has been suggested that diabetes may be a consequence rather than a cause of pancreatic cancer. 16-18 We have previously demonstrated folate deficiency in the majority of chronic pancreatitis patients, more so in tropical chronic pancreatitis; and that folate deficiency appeared to be the key factor in hyperhomocysteinemia in chronic pancreatitis patients. 19-20 There is epidemiological evidence linking folate deficiency to the development of pancreatic cancer. Aberrant DNA methylation could be a leading mechanism for development of carcinogenesis in chronic pancreatitis, an area which needs closer scrutiny, as the effects of folate on DNA methylation seem to be complex. Genetic factors especially PRSS1 mutations are implicated in development of cancer in hereditary pancreatitis. 21-22 The genetic risk for development of cancer in TCP has not been established, 23 however, the frequently noticed familial aggregation does suggest that genetic factors may have a role in carcinogenesis and this is an area which merits further studies in ICP/TCP. Concurrent diagnosis of pancreatic cancer and CP was more common in ACP than TCP but the difference was not significant. Among the 8 TCP patients who developed cancer before 40 years of age, 3 (37.5%) had a concurrent diagnosis of pancreatic cancer and CP. The possibility that these patients had increased risk by way of genetic factors is an interesting hypothesis, however we did not evaluate genetic factors in this study. An important finding in our study was that a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer at a stage when curative resection could be offered remains a challenge. Pancreaticoduodenectomy was feasible in less than one-fourth of our CP patients with pancreatic cancer. Interestingly, there was significant difference in rates of resectable tumors between ACP and TCP patients (10% vs. 25%). Although the risk of developing cancer at a younger age in TCP patients appeared to be less in this study as compared to previous studies, there are likely better prospects of diagnosing cancer at a stage where curative resection could be offered among TCP patients in whom disease onset is earlier than ACP patients. Hence there is a need to identify appropriate screening tools, especially in TCP patients. Serum CA 19-9 had been the most studied tumor marker and is most widely used in clinical practice. A report from India did suggest that it is a useful marker, especially in the absence of jaundice. 23 Our study, however, did not show an unequivocal benefit. Combination of serum CA 19-9 with other available markers may be better than CA 19-9 alone. There is urgent need to identify novel biomarkers which can reliably diagnose pancreatic cancer at an early stage in CP. EUS for screening for pancreatic cancer in CP is an attractive proposition as it does not carry the risk of radiation and is now available in many centers though its benefit has not yet been established. Moreover, the large calculi burden is a limiting factor in EUS imaging in Indian CP patients. Furthermore, differentiation of cancer from an inflammatory mass in CP remains a clinical dilemma despite advances in imaging like multidectector CT scan and EUS. EUS guided FNA has been useful but negative FNA does not completely exclude foci of cancer. Contrast enhanced and EUS elastography are likely to be useful adjuncts to conventional EUS studies but their benefit in this setting has not yet been established. In conclusion, the onset of pancreatic cancer in young patients with CP appears to be uncommon in ICP/TCP in the present series. Diabetes mellitus and smoking were risk factors associated with pancreatic cancer. The devastating nature of pancreatic cancer, a poor prognosis even with curative resection, and detection usually occurring at advanced stages, necessitate the need for further studies to understand the etiopathogenesis and identify risk factors. ICP forms a large burden of CP in India, hence understanding the etiological factors including genetic as well as environmental factors may help in this undertaking. In addition to efforts at better understanding genetic factors and attempts to quantify the genetic risk, there is also a need to determine the role of measures like correction of micronutrient deficiencies e.g. folate supplementation in reducing the risk of cancer.

References - Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P, Cavallini G et al. Pancreatitis and the risk of pancreatic cancer. International pancreatitis study group. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1433-7.

- Chari ST, Mohan V, Pitchumoni CS, et al. Risk of pancreatic carcinoma in tropical calcifying pancreatitis: an epidemiologic study. Pancreas. 1994;9:62-6.

- Augustine P, Ramesh H. Is tropical pancreatitis premalignant? Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:1005-8.

- Mori M, Harihran M, Anandkumar M, et al. a case control study on risk factors for pancreatic disease in Kerala, India. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:25-30.

- Balakrishnan V, Unnikrishnan AG, Thomas V, et al. Chronic pancreatitis. A prospective nationwide study of 1,086 subjects from India. JOP. 2008;2:593-600.

- Balakrishnan V, Nair P, Radhakrishnan L, Narayanan VA. Tropical pancreatitis - a distinct entity, or merely a type of chronic pancreatitis? Indian J Gastroenterol 2006; 25:74-81.Balakrishnan V, Kumar H, Sudhindran S, Unnikrishnan AG (eds). Chronic Pancreatitis and Pancreatic Diabetes in India. Kochi: Indian Pancreatitis Study Group. 2005.

- Rajesh G, Girish BN, Panicker S, Balakrishnan V. Time trends in etiology of chronic pancreatitis in South India. Trop. Gastroenterol. 2014; 35(3):164-7.

- Rajesh G, Veena AB, Saumya M, Balakrishnan V. Clinical profile of early-onset and late-onset idiopathic chronic pancreatitis in Southern India. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2014;33(3):231-6

- Midha S, Khajuria R, Shastri S, Kabra M, Garg PK. Idiopathic chronic pancreatitis in India: phenotypic characterisation and strong genetic susceptibility due to SPINK1 and CFTR gene mutations. Gut. 2010;59(6):800-7.

- Bosetti C, Lucenteforte E, Silverman DT et al. Cigarette smoking and pancreatic cancer: an analysis from the International Pancreatic Cancer Case-Control Consortium (Panc4). Ann Oncol. 2012;23(7):1880-8.

- Arem H, Reedy J, Sampson J, Jiao L, Hollenbeck AR, Risch H, Mayne ST, Stolzenberg-Solomon RZ. The Healthy Eating Index 2005 and risk for pancreatic cancer in the NIH-AARP study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(17):1298.

- Burney PG, Comstock GW, Morris JS. Serologic precursors of cancer: serum micronutrients and the subsequent risk of pancreatic cancer. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989;49(5):895

- Larsson SC, Wolk A. Red and processed meat consumption and risk of pancreatic cancer: meta-analysis of prospective studies. Br. J. Cancer. 2012;106(3):603.

- Batabyal P, Vander Hoorn S, Christophi C, Nikfarjam M. Association of diabetes mellitus and pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a meta-analysis of 88 studies. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:2453-62.

- Gullo L, Pezzilli R, Morselli-Labate AM, Italian Pancreatic Cancer Study Group. Diabetes and the risk of pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(2):81.

- Chari ST, Leibson CL, Rabe KG, Timmons LJ, Ransom J, de Andrade M, Petersen GM. Pancreatic cancer-associated diabetes mellitus: prevalence and temporal association with diagnosis of cancer. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(1):95.

- Pannala R, Leirness JB, Bamlet WR, Basu A, Petersen GM, Chari ST. Prevalence and clinical profile of pancreatic cancer-associated diabetes mellitus. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(4):981.

- Girish BN, Vaidyanathan K, Rao AN, Rajesh G, Reshmi S, Balakrishnan V. Chronic pancreatitis is associated with hyperhomocysteinemia and derangements in transsulfuration and transmethylation pathways. Pancreas. 2010;39(1):e11-6.

- Rajesh G, Girish BN, Vaidynathan K, Saumya M, Balakrishnan V. Folate deficiency in chronic pancreatitis. JOP.2010;11(4):409-10.

- Howes N, Lerch MM, Greenhalf W et al. Clinical and genetic characteristics of hereditary pancreatitis in Europe. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:252-61.

- Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P, DiMagno EP, et al. Hereditary pancreatitis and the risk of pancreatic cancer. International Hereditary Pancreatitis Study Group. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:442.

- Rajesh G, Elango EM, Vidya V, Balakrishnan V. Genotype phenotype correlations in 9 patients with tropical pancreatitis and identified gene mutations. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2009;28(2):68-71.

- Bedi MM, Gandhi MD, Jacob G et al. CA 19-9 to differentiate benign and malignant masses in chronic pancreatitis: is there any benefit? Indian J Gastroenterol. 2009;28:24-7.

|

|

|

|

|

|