|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Original Articles |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

Bleeding per rectum; fibromuscular obliteration; polypoidal lesion |

|

|

MK Behera, VK Dixit, SK Shukla, JK Ghosh, VB Abhilash, PK Asati, AK Jain

Department of Gastroenterology,

Institute of Medical Sciences,

Banaras Hindu University,

Varanasi, UP -221005,

India

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Manas Kumar Behera

Email: drmanasbehera@yahoo.co.in

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.298

Abstract

Background: Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (SRUS) is a chronic, benign defecation disorder often related to excessive straining. SRUS is diagnosed on the basis of clinical symptoms, endoscopic and histological findings.

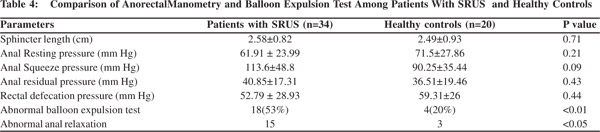

Methods: All patients diagnosed with SRUS by colonoscopy and confirmed by histopathology from October 2012 to August 2014 in the Department of Gastroenterology, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, India, were included in the study. Out of 92 patients, thirty-four patients underwent anorectal manometry. Twenty age-matched healthy volunteers were also studied with anorectal manometry to serve as controls.

Results: Mean age of the group was 41±19 years with age range of 10–82 years; males were 58 (63%) with male to female ratio of 1.7:1. Bleeding per rectum was present in 83%, constipation in 46.7%, abdominal pain in 27.2 %, and diarrhea in 25 % of the patients. On endoscopy, ulcerative lesions were seen in 83% patients of whom solitary and multiple lesions were present in 44% and 39%, respectively. Polypoidal lesions were reported in 17.4% whilst rectal polyps and erythematous mucosa were found in 5.4% and 2.2%, respectively. Histological examination revealed fibromuscular obliteration in 100% of patients, surface ulceration in 70.6% and crypt distortion in 20.65% of patients. Anal relaxation and balloon expulsion test was significantly abnormal in SRUS patients compared to healthy controls (53% vs. 20%, p< 0.01).

Conclusion: Rectal bleeding was the most common symptom and ulcerative lesions the most common endoscopic finding. Fecal evaluation disorder was more prevalent inpatients with SRUS.

|

48uep6bbphidvals|1362 48uep6bbphidcol2|ID 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (SRUS) is a chronic and benign rectal disorder affecting all age groups and usually presents with rectal bleeding or mucoid secretion from the rectum, chronic constipation, abdominal pain, straining, and sensation of incomplete evacuation. It may be considered part of a spectrum of diseases like anterior mucosal prolapse, SRUS and full thickness rectal prolapse.[1-3]

Pathophysiologic mechanism causing SRUS is poorly known. Most proposed etiopathogenetic mechanism of SRUS is chronic mucosal hypoperfusion leading to ischemic injury of the rectal mucosa. This can lead to paradoxical contraction of the pelvic floor muscles causing mucosal prolapse and pressure necrosis of the rectal mucosa.[4-6] SRUS is an infrequent, unrecognized and misdiagnosed disorder, with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 100 000 persons per year.[7] Due to a wide range of clinical symptoms and endoscopic findings, SRUS may often simulate other disorders such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and neoplasms causing difficult-to-manage lower gastrointestinal symptoms and delayed diagnosis.[8,9]

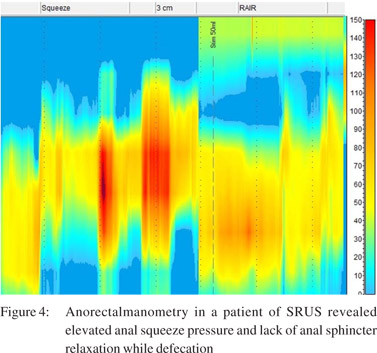

The diagnosis of SRUS is based on symptomatology in combination with endoscopic and histologic findings. The endoscopic spectrum of SRUS may vary from simple hyperemic mucosa to small or giant ulcers to broad-based polypoid lesions in different sizes and numbers. SRUS is a misnomer since neither are the lesions always solitary nor are they always ulcerative. Furthermore, they can also affect regions other than the rectum.[10] Anorectal manometry (ARM) can assess the functional status of the anorectum including resting tone, squeeze pressure of the anal sphincter, rectal sensation, rectoanal inhibitory reflex and in combination with balloon expulsion test can diagnose pelvic floor dyssynergia. Patients can be provided with biofeedback training based on anorectal manometry findings.[11]

There are very few studies from India evaluating clinical, endoscopic, histologic and anal manometry findings in patients with SRUS. Thus we conducted a prospective study to evaluate changes on anorectal manometry in patients of SRUS compared with healthy controls. We also evaluated clinical, endoscopic and histologic findings in patients of SRUS prospectively.

Methods

Study Design

Ninety-two patients of SRUS diagnosed by colonoscopy and confirmed by histopathology during the period from October 2012 to August 2014 in the Gastroenterology department of Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, India were included in the study. Of these, thirty-four patients had undergone anorectal manometry. Patients who underwent anorectal surgery in the past or had associated inflammatory bowel diseases were excluded from the study.

Twenty age-matched healthy volunteers were included to serve as controls. Clinical evaluation, anorectal manometry and balloon expulsion test were also undertaken in all the controls. All patients and controls consented to participate in the study. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee.

Colonoscopy and histopathology

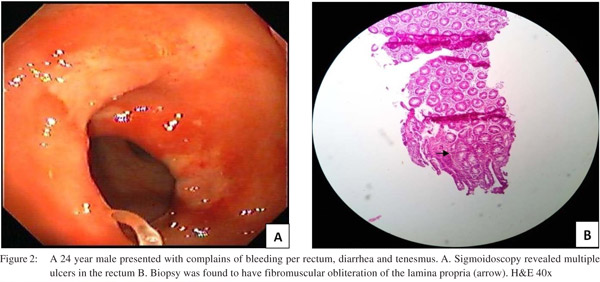

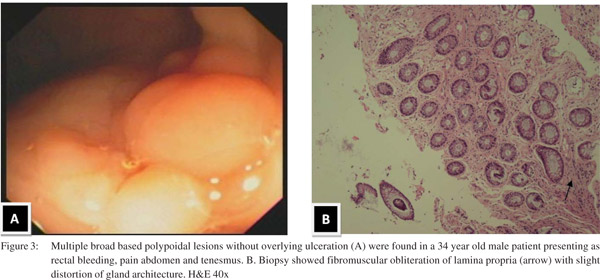

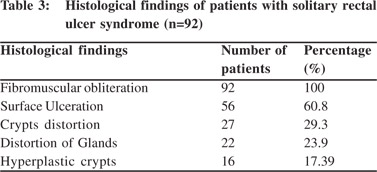

On endoscopy, the lesions were divided on the basis of number, as solitary or multiple, and on the basis of appearance as ulcerative polypoidal/nodular. The histological features included were fibromuscular obliteration, surface ulceration, crypts and mucosal gland distortion and hyperplasia, splaying of smooth muscle cells and fibrosis of the lamina propria. The hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) slides were reviewed by two authors to confirm the diagnosis.

Anorectal manometry

Each patient underwent ARM using a water perfusion manometry system (Sandhill Scientific inc., Highland Ranch, CO, USA) as per the standard technique.[12,13] An eight-lumen manometry catheter with balloon was used. The manometry catheter was inserted deep inside the rectum with the patient in the left lateral position. The catheter was subsequently pulled down slowly to be positioned at the high-pressure zone of the sphincter with a few upper ports in the rectum and a few lower ports outside the anus. The lengths of the sphincter zone and resting sphincter pressure were estimated from an average of length and pressure data obtained. Subsequently the patient was asked to bear down and residual anal sphincter pressure was estimated and change in sphincter pressure on squeezing was measured. Abnormal anal relaxation is defined as patients with 20% anal relaxation from baseline.

Analysis of manometry signal

The ARM signal was analyzed using BioVIEW™ Software (Sandhill Scientific). Resting anal pressure is defined as the difference between the intrarectal pressure and the maximum anal sphincter pressure at rest, a resting pressure of more than 68 mmHg is abnormal. Maximum squeeze pressure is defined as the difference between the intrarectal pressure and the highest pressure that is recorded at any level within the anal canal during the squeeze maneuver. Squeeze pressure more than 164 mm Hg was considered abnormal. A length of anal high pressure zone, more than 3.6 cm in females, and more than 4 cm in males, was considered abnormal (high).[14]

Balloon expulsion test

This test provides an assessment of an individual’s ability to expel a simulated stool. A latex balloon, tied on the tip of a thin catheter was placed inside the rectum and filled with 50 mL of warm water. The patient was asked to expel this while lying in left lateral position. If the balloon could be expelled without or with addition of weight of up to 200g on the other end of the catheter, it was considered normal.

Statistics

The data was analyzed on the SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and frequency analysis performed. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables as number of patients and percentages in parenthesis. Continuous data were analyzed using independent t test. P-values below 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Ninety-two patients with colonoscopic features of SRUS, confirmed by histopathology, were evaluated. The mean age of the group was 41±19 years with age range of 10–82 years; male patients comprised 58 (63%) with male to female ratio of 1.7:1.

Clinical characteristics

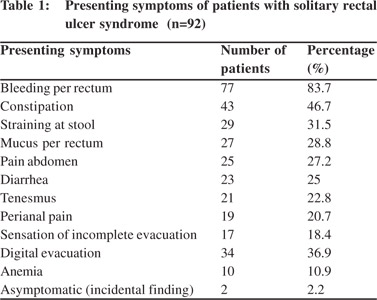

The most common symptom was bleeding per rectum affecting 77 (83%) patients followed by constipation (47%), straining on stool (31.5%), mucus passage per rectum (28.8%), pain abdomen (27.2%), and diarrhea in 25% of patients. Manual digital evacuation was reported in 34 (36.9%) patients and perianal pain in 20% of patients (Table 1).

Colonoscopy and histopathology findings

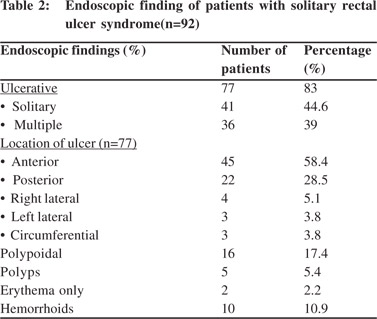

Endoscopic findings as shown in Table 2 revealed solitary lesions (Figure 1A) and multiple lesions (Figure 2A) in 41 (44.6%) and 36 (39%) patients, respectively. Seventy-seven (83%) of the lesions were ulcerative on the basis of appearance and 16(17%) were polypoidal (Figure 3A). Five (5.4%) patients had polyps and 2 (2.2%) had erythematous mucosa. Internal hemorrhoids were reported in 10 (10.9%) patients. The distance from the anal verge ranged from 3 to 18 cm, with 54 of 92 (58.5%) being between 6 and 10 cm. The locations of the ulcers are shown in Table 2. Histological examination revealed fibromuscular obliteration in 100% of patients, surface ulceration in 65 (70.6%) and crypt distortion in 19 (20.65%) patients (Figure 1B, 2B, 3B).

Anorectal manometry and balloon expulsion test in patients with SRUS and controls (Table 4) Sphincter length, anal resting pressure, anal squeeze pressure, anal residual pressure and rectal defecation pressure were comparable in patients of SRUS and healthy controls. The balloon expulsion test was significantly abnormal in SRUS patients compared to that in healthy controls (53% vs. 20%, p< 0.01). Abnormal anal relaxation as shown in Figure 4 was more frequently found in SRUS patients than in controls. (15 vs. 3, p<0.05).

Discussion

The etiopathogenesis of solitary rectal ulcer syndrome is still unknown. Mucosal ischemia was initially thought the culprit. Recently, fecal evacuation disorder was found to have a role in the pathogenesis of SRUS in a few small uncontrolled trials.[15,16] In the present study, the SRUS patients had higher functional evacuation disorder compared to healthy controls. This was documented by abnormal balloon expulsion test and impaired anal relaxation. Although the pathophysiologic mechanism is not completely known, mucosal hypoperfusion is the most proposed mechanism. Our study has suggested a role of functional evacuation disorder in the pathogesis of SRUS. In a recent prospective case control study from India, 17 of 40 SRUS patients had functional evacuation disorder.[17] In another recent controlled study, functional evacuation disorder was more common in the 11 patients with SRUS than in the 15 controls.[18] However, our study is one of the largest case control study showing association of SRUS with functional evacuation disorder.

SRUS is a chronic benign disorder with diverse clinical and endoscopic features. This entity is under-diagnosed both clinically and also on histopathology. The most common diagnostic confusion was with inflammatory bowel disease and neoplastic polyp.[1,19,20] A typical solitary rectal ulcer is a shallow ulcer surrounded by hyperemic mucosa most frequently found on the anterior wall of the rectum at 5 to 10cm from the anal verge.[21]

In our study, the mean age of patients was 46 years and males constituted 64% of all patients. Most of the studies noted a slightly higher proportion of female patients but two series commented on slight male predominance.[5,20,22-24] SRUS is more common in young adults compared to children and elder persons.[21] The most common presenting symptoms of SRUS in the present study were rectal bleeding and constipation. Rectal bleeding was of mild degree and no patient required blood transfusion. Large number of patients also complained of abdominal pain and diarrhea whilst mucus per rectum and perianal pain was encountered less frequently. These findings correspond to the observations from previous studies.[1,4,25] Manual digital evacuation is one of the most important factors causing direct injury to the rectal mucosa and bleeding in SRUS. In our study, 34 patients reported digital evacuation. One study has reported low number of patients with history of digital evacuation due to hesitation on the part of the patients in revealing it to the physician or unwillingness to have them documented in records.[5]

The endoscopic findings in the present study revealed ulcerative lesion in 87% of patients with solitary lesion in only 44 %, hence the term SRUS is misleading. This study demonstrated polypoidal lesion in 17% of patients. The polypoidal variant of SRUS is most often misdiagnosed as it mimics other commonly encountered diseases such as inflammatory polyp and rectal carcinoma. Hence, there is profound variability of endoscopic presentation of SRUS. Most of the lesions were located on the anterior wall of rectum at 5 to 10 cm from the anal verge. The anterior location of the ulcer is probably due to excessive straining during defecation.

Histopathology is mainspring for the diagnosis of SRUS and also for excluding any other underlying diseases. The histological findings are highly characteristic despite the inconsistency and discrepancy on the clinical and endoscopic findings. Key histological features include fibromuscular obliteration of the lamina propria with splaying of muscularis mucosa upward between the crypts, thickened mucosa and glandular distortion.[1,5] However, these morphological features can also be seen in other benign defecation disorders including rectal prolapse, and inflammatory polyp.[26,27] The SRUS is differentiated from inflammatory bowel disease and chronic ischemic colitis by presence of collagen infiltration of the lamina propria.[28] Biopsy is also mandatory in patients with endoscopic evidence of SRUS to rule out malignancy.

In our study, we found fibromuscular obliteration in all cases and surface ulceration in more than half of the patients. Less commonly encountered findings were crypt distortion, mucosal gland distortion and hyperplastic crypts. Our findings were at par with the study by Abid et al of 116 patients from Karachi, Pakistan.[5] In another study by Al Brahmin et al, authors had found surface ulcerations and crypt distortion in all 13 patients.[4]

Many studies have stressed the association of deeper malignancy in patients of SRUS. One of the previous studies documented that malignant tumors might present with histological findings suggestive of SRUS initially and later develop characteristics of malignancy, which suggests SRUS has the potential of progressing to malignancy.[29] Another study also found that initial histopathology did not reveal the concealed malignancy which was later revealed.[5] In this study, we found 2 cases of rectal adenocarcinoma, initially misdiagnosed as SRUS.

In conclusion, functional evacuation disorder was more common inpatients with SRUS as evidenced by abnormal balloon expulsion test and sphincter relaxation. Rectal bleeding and constipation were the most common presentations. Ulcerative lesions were the most frequent endoscopic observations encountered followed by polypoidal lesions.

References

- Suresh N, Ganesh R, Sathiyasekaran M. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome: a case series. Indian Pediatr. 2010;47:1059–61.

- Blackburn C, McDermott M, Bourke B. Clinical presentation of and outcome for solitary rectal ulcer syndrome in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;54:263–5.

- Sun WM, Read NW, Donnelly TC, Bannister JJ, Shorthouse AJ. A common pathophysiology for full thickness rectal prolapse, anterior mucosal prolapse and solitary rectal ulcer. Br J Surg. 1989;76:290–95.

- Al-Brahim N, Al-Awadhi N, Al-Enezi S, Alsurayei S, Ahmad M. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome: a clinicopathological study of 13 cases. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:188–92.

- Abid S, Khawaja A, Bhimani SA, Ahmad Z, Hamid S, Jafri W. The clinical, endoscopic and histological spectrum of the solitary rectal ulcer syndrome: a single-center experience of 116 cases. BMC Gastroenterology. 2012;12:72.

- Rao SS, Ozturk R, De Ocampo S, Stessman M. Pathophysiology and role of biofeedback therapy in solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:613–8.

- Martin CJ, Parks TG, Biggart JD. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome in Northern Ireland. 1971–1980. Br J Surg.1981;68:744–74.

- Saul SH, Sollenberger LC. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. Its clinical and pathological underdiagnosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1985;9:411–21.

- Britto E, Borges AM, Swaroop VS, Jagannath P, DeSouza LJ. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. Twenty cases seen at an oncology center. Dis Colon Rectum. 1987;30:381–5.

- Tjandra JJ, Fazio VW, Church JM, Lavery IC, Oakley JR, Milsom JW. Clinical conundrum of solitary rectal ulcer. Dis Colon Rectum.1992;35:227–34.

- Pucciani F, Rottoli ML, Bologna A, Cianchi F, Forconi S, Cutellè M,, et al. Pelvic floor dyssynergia and bimodal rehabilitation: results of combined pelviperinealkinesitherapy and biofeedback training. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1998;13:124–30

- Azpiroz F, Enck P, Whitehead WE. Anorectal functional testing: review of a collective experience. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:232–40.

- Jorge JM, Wexner SD. A practical guide to basic anorectal physiology investigations. Contemp Surg. 1993;43:214–24.

- Lee HJ, Jung KW, Han S, Kim JW, Park SK, Yoon IJ, et al. Normal values for high-resolution anorectalmanometry/topography in a healthy Korean population and the effects of gender and body mass index. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;26:529–37.

- Kuijpers HC, Schreve RH, ten Cate Hoedemakers H. Diagnosis of functional disorders of defecation causing the solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. Dis Colon Rectum. 1986;29:126–9.

- Simsek A, Yagci G, Gorgulu S, Zeybek N, Kaymakcioglu N, Sen D. Diagnostic features and treatment modalities in solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. Acta Chir Belg. 2004;104:92–6.

- Sharma A, Misra A and Ghoshal UC. Fecal Evacuation Disorder Among Patients With Solitary Rectal Ulcer Syndrome: A Casecontrol Study. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;20:531–8

- Rao SS, Ozturk R, De Ocampo S, Stessman M. Pathophysiology and role of biofeedback therapy in solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:613–8.

- Jarrett ME, Emmanuel AV, Vaizey CJ, Kamm MA. Behavioral therapy (biofeedback) for solitary rectal ulcer syndrome improves symptoms, mucosal bloodflow. Gut. 2004;53:368–70.

- Knoepp LF, Davis WM. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome: not always ulcerated. South Med J. 1992;85:1033–4.

- Sharara AI, Azar C, Amr SS, Haddad M, Eloubeidi MA. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome: endoscopic spectrum and review of the literature. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005,62:755–62.

- Chiang JM, Changchien CR, Chen JR. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome an endoscopic and histological presentation and literature review. Int J Colorectal Dis.2006;21:348–56.

- Marchal F, Bresler L, Brunaud L, Adler SC, Sebbag H, Tortuyaux JM, et al. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome: a series of 13 patients operated with a mean follow-up of 4.5 years. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2001;16:228–33.

- Bulut T, Canbay E, Yamaner S, Gulluoglu M, Bugra D. Solitary Rectal Ulcer Syndrome: Exploring Possible Management Options. Int Surg. 2011;96:45–50.

- Chong VH, Jalihal A. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome: characteristics, outcomes and predictive profiles for persistent bleeding per rectum. Singapore Med J. 2006,47:1063–8.

- Tendler DA, Aboudola S, Zacks JF, O’Brien MJ, Kelly CP. Prolapsing mucosal polyps: an underrecognized form of colonic polyp–a clinicopathological study of 15 cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002,97:370–6.

- Chetty R, Bhathal PS, Slavin JL. Prolapse-induced inflammatory polyps of the colorectum and anal transitional zone. Histopathology. 1993;23:63–7.

- Levine DS, Surawicz CM, Ajer TN, Dean PJ, Rubin CE. Diffuse excess mucosal collagen in rectal biopsies facilitates differential diagnosis of solitary rectal ulcer syndrome from other inflammatory bowel diseases. Dig Dis Sci. 1988,33:1345–52.

- Li SC, Hamilton SR. Malignant tumors in the rectum simulating solitary rectal ulcer syndrome in endoscopic biopsy specimens. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:106–12.

|

|

|

|

|

|