|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Quarterly Reviews |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

Eosinophilic esophagitis, gastroesophageal reflux disease, dysphagia, chronic inflammation |

|

|

Saurabh Kedia, Bhaskar Jyoti Baruah, Govind Makharia, Vineet Ahuja

Department of Gastroenterology,

All India Institute of Medical Sciences,

New Delhi, India

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Vineet Ahuja

Email: vineet.aiims@gmail.com

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.277

Abstract

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a clinico-pathological entity characterised by symptoms of esophageal dysfunction and eosinophilia on esophageal mucosal biopsies in the absence of other causes of esophageal eosinophilia. It is a chronic inflammatory condition of esophagus often characterized by refractory reflux symptoms in children and dysphagia in adults. It occurs as a result of Th2 inflammatory response to environmental triggers (food antigens) in genetically predisposed individuals. The diagnostic criteria include symptoms of esophageal dysfunction, esophageal eosinophilia (> 15/hpf), and a PPI trial (persistent eosinophilia after 8 weeks of PPI). Mainstay of treatment at present is topical steroids and dietary therapy. Maintenance treatment should be considered to prevent long term complications.

|

48uep6bbphidvals|1341 48uep6bbphidcol2|ID 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a clinico-pathological entity characterised by symptoms of esophageal dysfunction and eosinophilia on esophageal mucosal biopsies in the absence of other causes of esophageal eosinophilia[1] Landres et al first described EoE in 1978. [2] Since then, there were very few reports on this disease till late 1990s,[3,4] when this condition started becoming increasingly recognised. It is a chronic inflammatory condition of esophagus often characterized by refractory reflux symptoms in children and dysphagia in adults. The definition, diagnostic and management approach has evolved considerably over the last two decades and the understanding about this disease is expected to improve further in the future. This review will try to provide latest information on the diagnostic and management approach to EoE.

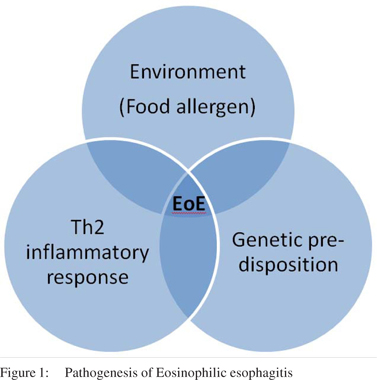

Pathogenesis

Eosinophilic esophagitis is a chronic inflammatory condition of the esophagus which is believed to occur as a result of Th2 inflammatory response[5] to environmental triggers (food antigens)[6,7] in genetically predisposed individuals (Figure 1). The cytokines responsible for the Th2 inflammatory response include Interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5[8] and IL-13[9,10] These cytokines stimulate the production and upregulation of Eotaxin-3 (potent eosinophilic chemokine) in the esophageal mucosa.[11] Eotaxin- 3 in turn causes recruitment of eosinophils to the esophageal mucosa.[12] These eosinophils secrete pro-inflammatory and fibrogenetic cytokines which cause tissue damage, recruit additional inflammatory cells such as mast cells and fibroblasts and cause tissue remodelling.[13] EoE represents a varied manifestation of atopy.[14-17] This is suggested by the fact that there is a significant allergic predisposition as concurrent alergic rhinitis, eczema or asthma seen in a majority of EoE patients.[18] Chronic esophageal inflammation leads to esophageal tissue remodelling and fibrosis which results in symptoms of dysphagia. TGF- â1 plays a pivotal role as a profibrotic factor in causing esophageal smooth muscle contraction and fibrosis.[19-21]

Genetics of EoE

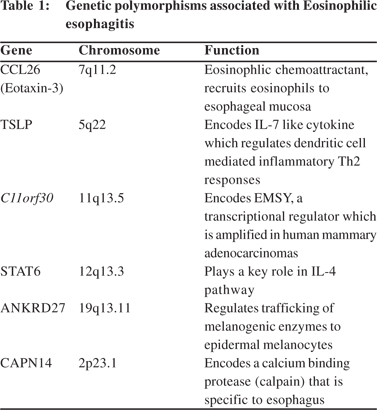

EoE occurs in multiple family members, in a non Mendelian manner suggesting a polygenic complex pattern of inheritance. EoE has been reported to have a racial as well as gender bias. Multiple epidemiological studies have shown predominance of european white ancestry and male gender amongst EoE patients.[22] Recent reports have suggested role of genetic polymorphisms in the pathogenesis of EoE.[23] A recent study showed that approximately 10% parents of EoE children had history of esophageal strictures and 8% had eosinophilic infiltrates on esophageal biopsies.[24] It has also been shown that EoE is associated with a sibling risk ratio of 80, which means that there 80 fold risk of developing EoE in a sibling of patient with EoE. Genome wide association studies have identified 6 loci which are associated with EoE (Table 1).

Eotaxin-3 (CCL26)[25] followed by Thymic stromal lymphoprotein (TSLP)[26,27] located on chromosome 5q22 were the first susceptibility genes associated with EoE. Other genetic loci include two loci which have previously been associated with other atopic and autoimmune diseases (c110rf30[28,29] and STAT628,[30]) and two EoE specific loci; ANKRD2728,[31] (regulates trafficking of melanogenic enzymes to epidermal melanocytes) and CAPN1428,[32] which encodes a calcium binding protease (calpain) that is specific to esophagus.

Epidemiology

EoE is increasingly being seen and recongnized possibly because of increasing incidence as well as awareness of the disease.[33-35] It has been predominantly reported from Western industrialized countries with high socioeconomic development. It has been shown that incidence of EoE in children may vary from 0.7 to 10/100,000 and prevalence from 0.2 to 43/100,000 depending on the geographic location.[36] In adult cohorts, the prevalence rate of 52/100,000 has been reported on the basis of a survey done in USA.[37] It is a disease of middle age adult males[38] as the average age of presentation is 30 to 50 years with 60-80% of all cases diagnosed being males.[39,40] In a recent study from our centre (unpublished), the prevalence of EoE in patients with GERD was 3.2%. Six out of 192 patients with GERD were diagnosed with EoE. Non response to PPI and history of allergy were predictive of diagnosis of EoE.

Clinical features

Symptoms depend upon the age of the patient. Children usually present with feeding difficulties, failure to thrive, abdominal pain, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, and regurgitation.[41,42] Dysphagia is the most common symptom in adolescents and adults, seen in 25 – 100% patients.[43,44] Other features include history of sudden onset food impaction,[45,46] chest pain and heartburn.[47] However the symptoms of EoE are very nonspecific and no symptom in isolation points towards the diagnosis of EoE. Approximately 60 – 80% children and fewer adults have a history of associated allergic diseases such as asthma, atopic dermatitis, atopic rhinitis and food allergies.[48-50]

EoE should always be considered as a possibility in the clincial scenario of heartburn refractory to anti reflux therapy.[51,52] However, a distinction should be made between proton pump responsive esophageal eosinophilia.[53] Peripheral eosinophilia is seen in 5-50% of patients and approximately three fourths of the patients have elevated total serum IgE levels.

Endoscopic features

Similar to clinical features, the endoscopic features are also non-specific and none of the features is pathgnomonic to EoE. The important features include concentric rings (corrugations), linear furrows, loss of vascular pattern due to mucosal edema, exudates or white plaques, narrow calibre esophagus, strictures and crepe paper esophagus (fragile esophageal mucosa which lacerates due to passage of endoscope).[54] The findings can occur together or in isolation. Approximately 10% patients can have normal endoscopic findings, and diagnosis can be missed if biopsies are not taken.[55] There is also a moderate degree of inter-observer and intra-observer variability in the interpretation of endoscopic findings as per two recent studies.[56,57] It is for this reason that biopsies should be obtained in all suspected cases of EoE even if the endoscopy is normal. Since the eosinophilic infiltrate in the esophagus is patchy, at least 4 biopsies should be obtained both from both proximal and distal esophagus for optimal yield.[58,59] A recent study showed that esophageal biopsy “pull” sign (resistance felt when pulling biopsy forceps to obtain tissue) was highly specific and treatment responsive endoscopic finding in EoE.[60]

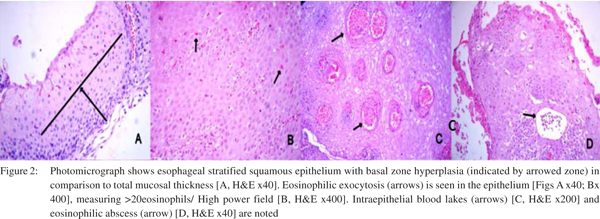

Histological features (Figure 2)

Eosinophils are normal constituents of gastrointestinal tract except the esophagus. The pathological characteristic of EoE is eosinophilic infiltrate in the esophageal epithelium, with greater than 15 eosinophils/hpf in at least one high power field suggesting the diagnosis of EoE. However like endoscopic features, the pathology is also non-specific and not pathognomonic for EoE and should be interpreted in association with clinical and endoscopic features.[61,62] Other histologic features include eosinophilic microabscesses (clusters of > 4 eosinophils), superficial layering of eosinophils, extracellular eosinophilic granules (comprising of eosinophil peroxidase, major basic protein and eosinophilic derived neurotoxin), rete peg elongation, basal cell hyperplasia, and lamina propria fibrosis.[63,64]

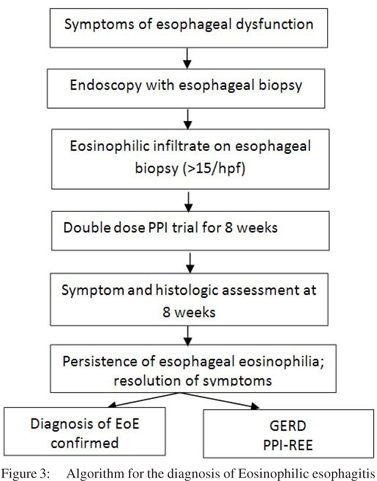

Diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis

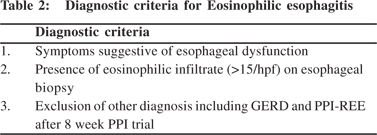

Diagnosis of EoE is made on the basis of clinical, endoscopic and histological features after exclusion of other etiologies. The closest differential of EoE includes two clinical entities: gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and proton pump inhibitor responsive esophageal eosinophilia (PPI-REE).[53,65,66] Other systemic conditions which can be associated with esophageal eosinophilia include other eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders, celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, hyper-eosinophilic syndrome, drug hypersensitivity, vasculitis and connective tissue disorders.[1,67] These disorders should be exluded before entertaining the diagnosis of EoE. There are 3 diagnostic criteria for the diagnosis of EoE (Table 2): a) symptoms of esophageal dysfunction, b) eosinophilic infiltrate (>15/hpf) of esophageal biopsy, and c) exclusion of other disorders, primarily GERD and PPI-REE (Figure 3).[67] The third criteria will be fulfilled after a PPI trial which consists of 8 week course of 20 – 40 mg twice daily of any available PPI.[68,69] Persistence of eosinophilic infiltrate after PPI trial excludes GERD and PPI-REE and diagnosis of EoE is confirmed. Approximately 1/3rd patients with symptoms of esophageal dysfunction and eosinophilic infiltrate respond clinically and histologically to PPI.[70]

Role of non-invasive modalities in differentiating EoE from GERD and monitoring treatment

Several groups have derived prediction tools and models to differentiate EoE from GERD and predict EoE without biopsy. Aceves et al[71] in a study of EoE and GERD patients showed that dysphagia, anorexia/ early satiety were more common in EoE. In another retrospective study it was shown that history of food impaction, PPI refractory heartburn and peripheral eosinophilia were predictive of EoE with a sensitivity of 91% and specificity of 100%.[72] Another group generated a predictive model in 163 paediatric and adult EoE and equal number of GERD cases. They showed that a set of 6 characteristics: male sex, history of dysphagia, heartburn, food impaction, and furrows and plaques on endoscopy were able to differentiate EoE from GERD with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.86.[73] Dellon et al[74] in a recent study developed a predictive model (based on clinical and endoscopic features) which could recognize patients (with symptoms of esophageal dysfunction) as having a very high possibility of EoE as well as those in whom there in very low possibility of EoE. This model included eight measures: age, sex, history of dysphagia and food allergy, presence of endoscopic rings, furrows, plaques and lack of hiatus hernia. As this model had a very high specificity and negative predictive value it could accurately identify patients unlikely to have EoE and could avoid biopsy.

A recent study examined the role of non-invasive biomarkers to monitor treatment response in EoE.[75] In patients randomized to placebo and budesonide, absolute esoinophil count (AEC), serum levels of CCL-17, CCl-18, CCl-26, eosinophilic cationic protein (ECP) and mast cell tryptase (MCT) were determined and correlated with symptoms, endoscopic scores and esophageal eosinophilic density. All of the above studied markers decreased significantly in the budesonide arm and correlated with decline in esophageal eosinophils. Of these markers AEC was shown to be the most valuable serum marker.

Treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis

Therapeutic Indications

The established indications to treat EoE are: presence of solid food dysphagia, to prevent food impaction and prevention of esophageal damage caused by tissue remodelling.[76] The non established indication for treatment is prevention of herpes simplex (HSV-1) esophagitis. The reason being that acute esophageal inflammation may be risk factor in immunocompetent individuals for HSV1 infection.[76]

Therapeutic goals

The primary goals of treating eosinophilic esophagitis include symptom improvement, histological improvement (elimination of esophageal eosinophilia), maintenance of symptomatic relief, minimization of adverse events and improvement in quality of life. It is still debatable if the therapeutic endpoint should be symptomatic improvement or histological remission.

The three primary treatment modalities are drugs, dietary therapy and endoscopic dilatation in selected cases.

Pharmacological treatment

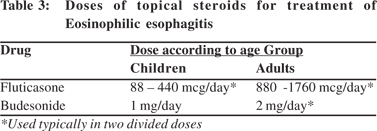

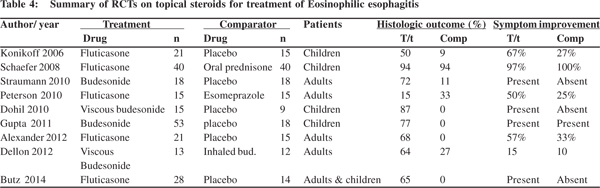

The mainstay of pharmacological treatment of EoE are topical corticosteroids, which include inhaled fluticasone, nebulizer solution of budesonide and oral viscous budesonide.[77] These preparations were primarily designed for asthma treatment (inhalers or nebulisation solutions), but instead of inhalation they are swallowed orally. When swallowed these preparations coat the esophageal mucosa and act locally. The primary treatment endpoints have varied in various trials including symptomatic and histological improvement. These trials also show that there is little correlation between symptomatic and histological resolution. Histological end points have also varied between various trials.

Fluticasone

Fluticasone is used in two divided doses (Table 3) as multidose inhaler which is swallowed orally. The medication should be administered directly into the mouth without the spacer, and without inhaling during actuation. The patient should not eat or drink for 30 minutes after swallowing the drug. All the three RCTS of fluticasone vs placebo (Table 4) showed significant improvement in esophageal eosinophilia. However the definition and degree of symptomatic improvement was different in all the three trials. The first trial by Konikoff et al in children showed improvement in vomiting in the treatment arm.[78-80] The other two trials did not show any significant improvement in patient symptoms.[78,79] Fluticasone has also been compared with oral prednisolone[81] and oral esomeprazole in two RCTs.[82,83] There was > 90% symptomatic and histologic improvement in both the fluticasone and prednisolone arms. However more patients had complete histological remission with prednisone as compared with fluticoasone (81% vs 50%). There was no difference in histologic response when fluticasone was compared with esomeprazole, however symptoms improved significantly with fluticasone. Fluticasone has also been used in nasal drop formulation, and was shown to be effective in a case series.

Budesonide

There are 4 RCTs on different forms of budesonide,[84-86] three have compared it with placebo and fourth one compared two different forms of budesonide (inhaled vs oral viscous).[87] All placebo controlled trials showed significant histological improvement. However, symptomatic improvement as compared to placebo was seen in two trials only. Oral viscous budesonide (OVB) was developed by mixing budesonide aqueous solution with sucralose to form a sweet and easy to swallow paste. A study which compared OVB to inhaled solution showed greater histologic improvement and higher mucosal medication contact as measured by scintigraphy with OVB. However there was no difference in the degree of symptomatic improvement in both the groups.

In addition to sucralose, budesonide has also been used with other forms of thickeners including corn starch, powdered sugar, honey and neocate nutra.[88] Budesonide has also been used as oral budesonide suspension (OBS), and in an RCT it was shown to be effective than placebo in histological and symptomatic improvement.[86]

A recent study which compared inhaled fluticasone and budesonide in EoE found equal efficacy for both topical steroid preparations in terms of histological and symptomatic response.[89]

Other topical steroid preparations

Other topical steroids which have been used for this indication include ciclesonide (used as multi-dose inhalers)90 and mometasone (used as nasal preparation).[91] Two recent systemic review and meta-analysis concluded that topical steroids were effective for histological remission; however the efficacy remains undetermined for symptomatic improvement and endoscopic remission.[92,93] There are no major side effects with topical steroids. The risk of adrenal suppression with topical steroids remains controversial. There are recent reports both in favour of[94,95] and against adrenal suppression[96] with the use of inhaled steroids in EoE. The rates of oral and esophageal candidiasis has also been low varying from 0 – 30% in various reports with most the cases being asymptomatic and detected incidentally.

Other pharmacological agents

Oral steroids: The RCT that compared fluticasone and prednisolone showed similar results.[81] However prednisolone was associated with greater degree of adverse events. Oral steroids are recommended when topical preparations are ineffective or when rapid improvement in symptoms is required.

Leukotriene antagonists: There are no controlled trials for these agents (monteleukast) in EoE. Case series in both children and adults did not show promising results.[97-98] These agents are therefore not recommended for treatment of EoE.

Mast cell stabilizers: Mast cells play a key role in pathogenesis of EoE. However based on their inefficacy in case series, they are not recommended for treating EoE.[99]

Immunomodulators (Azothioprine/ 6-mercaptopurine (MP)): Three adults with steroid refractory disease were successfully treated with azathioprine and remained in remission till the treatment was continued. However the data on use of these agents is still scarce,[100] and they are not recommended as first line maintenance agents for treatment of EoE.

Biologics: Interleukin-5 is a key player in the pathogenesis of EoE. Antibodies to IL-5, mepolizumab and reslizumab[101] have been studied for the treatment of EoE.[102-104] There have been case series and RCTs on the use of these antibodies and have demonstrated modest decline in esophageal eosinophilia, with no significant improvement in symptoms. Another class of antibodies against IgE (omalizumab) also did not show any histological or symptomatic improvement.[105] These agents are therefore not recommended for use in EoE. A small case series of anti TNF antibodies in EoE also did not show any benefit.[106]

Dietary therapy

Food allergens are the most important environmental factors that play a significant role in the pathogenesis of EoE.[107] Therefore avoidance of food antigens would be an important therapeutic strategy for EoE. There are three strategies for dietary approach in EoE; elemental diet, targeted elimination diet (after allergic testing) and six food elimination diet (SFED).

Elemental diet comprises of amino acids, basic carbohydrates and medium chain tri-glycerides. It therefore eliminates all possible antigens from the diet. Several case series from children have shown excellent symptomatic as well as histological response.[108-109] However studies in adults did not replicate the results in children, probably because of low compliance in adults.[110] Although it is associated with excellent outcomes, elemental diet is unpalatable, and is associated with a very poor compliance especially in adults. It is also expensive and may require enteral feeding tube for administration. Because of problems associated with elemental diet a dietary approach was developed which eliminated six food items that were most strongly associated with food allergy.[111,112] These include milk, egg, wheat, soy, sea food and nuts. Studies in both children and adults have shown good symptomatic as well as histological response, comparable with elimination diet. Reintroduction with these food items showed that wheat and milk were the most common food triggers.[113] The third dietary approach consists of allergic testing to eliminate possible food allergens.[114] The possible strategies for allergic testing include skin prick and patch testing.[115,116] However the best approach for allergic testing is still debatable.

The response rates with this approach have been modest ranging from 50 – 70% in children and bit lower in adults.[117] A recent meta-analysis which included 1317 patients (1128 children, 189 adults) from 33 studies compared histological response will all the above mentioned strategies.[118] Elemental diet was the most effective (90.8%) followed by SFED (72.1%). Targeted dietary approach was the least effective (45.5%). There was no significant difference in the efficacy of dietary interventions between adults and children (67.2% vs 63.3%). Maintenance therapy for EoE The duration of treatment in various trials of pharmacological and dietary therapy has varied from 2 weeks to 16 weeks. However, very few trials have assessed the role of these agents in maintenance of remission. Since EoE is a chronic inflammatory condition relapse is expected after initial induction of remission once the treatment is stopped. Therefore, to prevent remodelling of esophageal mucosa and long term complications remission once achieved should be maintained. In a study[119] which randomized patients to budesonide (0.5 mg/day) vs placebo after achieving remission, there was universal histological recurrence in the placebo group as compared to 50% is the budesonide group. Symptomatic recurrence was also less in budesonide arm as compared to placebo (36% vs 64%). In another study inhaled fluticasone was used in a high dose (1760 mcg/day) for attaining remission.80 After 3 months of therapy, patients who achieved complete remission (CR) were started on half of the initial dose (880 mcg/day). Sixty five percent patients achieved CR during induction. Of these 65% patients, 73% remained in remission on low dose fluticasone. Regarding the role of dietary therapy in maintenance a prospective study was conducted on six food elimination diet (SFED) in 67 adults with EoE.[120] These patients were induced with SFED for 6 weeks and subsequent re-introduction with each of the single food item was done followed by endoscopies and biopsies. Food item was considered as a trigger if esophageal eosinophilia (>15/hpf) reappeared on follow-up biopsies. Patients who continued to avoid the offending food item remained in clinical and histological remission for up to three years. However the duration of maintenance therapy still remains unclear and should be individualized. In patients refractory to topical steroids and dietary therapy, induction can be achieved with oral steroids and remission can be maintained with immunomodulators as was shown in a small case series.[100]

Role of endoscopic dilatation

Endoscopic dilatation is indicated in patients with esophageal strictures or with narrow calibre esophagus, who have significant symptoms of dysphagia after adequate pharmacological and dietary therapy. Esophageal dilatation improves symptoms of dysphagia effectively[121] with one study reporting 81% symptomatic response at 3 months post dilatation.[122] However, esophageal dilatation should be deferred during the first endoscopy, before any therapy has been started. This is based on a recent RCT in which 31 patients were randomized to dilatation vs no dilatation.[123] Seventeen patients underwent esophageal dilatation before medical therapy and 14 patients were kept on medical therapy alone. There was no additional advantage of esophageal dilatation in improvement of dysphagia.

Initial reports of dilatation in patients with EoE, raised many alarms as it was associated with high rates of complications including post dilatation chest pain, esophageal tears, and esophageal perforation which was seen in as high as 8% dilatations.[124] However recent studies including two systematic reviews have negated this concern and cumulative data on over 1000 dilatations has revealed a perforation rate of 0.3% only[125,126] which is similar to the rates associated with dilatation for other indications. Secondly all these perforations were managed conservatively and none required operative interventions. Therefore currently dilatation is an accepted therapeutic modality for EoE if performed cautiously. There is no definite consensus over the technique of dilatation (bougie vs balloon). Both techniques have their own advantages and limitations and the preferred technique depends upon the type of stricture and individual preference.

Investigational agents

As new information on the pathogenesis of EoE is being discovered several new treatment modalities are being discovered.

Anti Il-13: Interleukin 13 is a Th2 cytokine that plays an important role in the pathogenesis of EoE, and has shown to be up regulated in the esophageal mucosa of EoE patients. In a study of 25 patients who were randomized to anti IL-13 antibody (QAX576) and placebo, there was histological and symptomatic, but statistically non-significant benefit with anti –IL13 antibody.[127] Further data is needed before this agent can be used in treatment of EoE.

CRTH2 antagonist: CRTH2 (Chemoattractant receptor homologous molecule expressed on TH2 cells) is a prostaglandin D2 receptor, implicated in various allergic diseases. CRTH2 antagonist OC000459 was studied in a RCT which randomized 26 patients to OC000459 and placebo.[128] There was a statistically significant reduction in esophageal eosinophilia with OC000459 as compared to placebo, however there was no difference in the degree of symptomatic improvement between the two groups.

Conclusion

Eosniophilic esophagitis is a chronic inflammatory disorder which is mediated by a Th2 inflammatory response in response to environmental/food allergens in individuals with genetic background. The diagnosis requires high index of suspicion, especially in young and middle age male patients with dysphagia, patients with PPI refractory heartburn, presence typical endoscopic features and eosinophilia on biopsy. The diagnostic criteria include symptoms of esophageal dysfunction, esophageal eosinophilia (> 15/hpf), and a PPI trial (persistent eosinophilia after 8 weeks of PPI). Mainstay of treatment at present is topical steroids and dietary therapy. Maintenance treatment should be considered to prevent long term complications. Esophageal dilatation should only be considered in patients who are symptomatic despite inhaled steroid/ dietary therapy. There is a lot of progress in the

understanding of pathogenesis of EoE which is opening up new dimensions in the diagnosis (including role of non-invasive markers) and treatment of these disease entity. There has been a considerable progress in identifying genetic polymorphism associated with EoE which in future could lead to development of targeted therapies for EoE.

References

- Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, Atkins D, Attwood SE, Bonis PA, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:3–20.

- Landres RT, Kuster GG, Strum WB. Eosinophilic esophagitis in a patient with vigorous achalasia. Gastroenterology. 1978;74:1298–1301.

- Van Rosendaal GM, Anderson MA, Diamant NE. Eosinophilic esophagitis: case report and clinical perspective. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1054–6.

- Hempel SL, Elliott DE. Chest pain in an aspirin-sensitive asthmatic patient. Eosinophilic esophagitis causing esophageal dysmotility. Chest. 1996;110:1117–20.

- Straumann A, Bauer M, Fischer B, Blaser K, Simon HU. Idiopathic eosinophilic esophagitis is associated with a T(H)2-type allergic inflammatory response. J Allergy Clin Immunol.2001;108:954–61.

- Mishra A, Hogan SP, Brandt EB, Rothenberg ME. An etiological role for aeroallergens and eosinophils in experimental esophagitis. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:83–90.

- Green DJ, Cotton CC, Dellon ES. The Role of Environmental Exposures in the Etiology of Eosinophilic Esophagitis: A Systematic Review. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:1400–10.

- Mishra A, Hogan SP, Brandt EB, Rothenberg ME. IL-5 promotes eosinophil trafficking to the esophagus. J Immunol. 2002;168:2464–9.

- Mishra A, Rothenberg ME. Intratracheal IL-13 induces eosinophilic esophagitis by an IL-5, eotaxin-1, and STAT6- dependent mechanism. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1419–27.

- Schmid-Grendelmeier P, Altznauer F, Fischer B, Bizer C,Straumann A, Menz G, et al. Eosinophils express functional IL- 13 in eosinophilic inflammatory diseases. J Immunol. 2002;169:1021–7.

- Kagami S, Saeki H, Komine M, Kakinuma T, Tsunemi Y, Nakamura K, et al. Interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 enhance CCL26 production in a human keratinocyte cell line, HaCaT cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;141:459–66.

- Rankin SM, Conroy DM, Williams TJ. Eotaxin and eosinophil recruitment: implications for human disease. Mol Med Today. 2000;6:20–7.

- Ying S, Meng Q, Zeibecoglou K, Robinson DS, Macfarlane A, Humbert M, et al. Eosinophil chemotactic chemokines (eotaxin, eotaxin-2, RANTES, monocyte chemoattractant protein-3 (MCP-3), and MCP-4), and C-C chemokine receptor 3 expression in bronchial biopsies from atopic and nonatopic (Intrinsic) asthmatics. J Immunol. 1999;163:6321–9.

- Fogg MI, Ruchelli E, Spergel JM. Pollen and eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:796–7.

- Hoffjan S, Nicolae D, Ober C. Association studies for asthma and atopic diseases: a comprehensive review of the literature. Respir Res. 2003;4:14. Print 2003.

- Spergel JM. Eosinophilic esophagitis in adults and children: evidence for a food allergy component in many patients. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;7:274–8.

- Wang FY, Gupta SK, Fitzgerald JF. Is there a seasonal variation in the incidence or intensity of allergic eosinophilic esophagitis in newly diagnosed children? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:451–3.

- Straumann A, Aceves SS, Blanchard C, Collins MH, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Pediatric and adult eosinophilic esophagitis: similarities and differences. Allergy. 2012;67:477–90.

- Kagalwalla AF, Akhtar N, Woodruff SA, Rea BA, Masterson JC, Mukkada V, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: epithelial mesenchymal transition contributes to esophageal remodeling and reverses with treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1387–96.

- Aceves SS. Remodeling and fibrosis in chronic eosinophil inflammation. Dig Dis. 2014;32:15–21.

- Cheng E, Souza RF, Spechler SJ. Tissue remodeling in eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;303:G1175–87.

- Sherrill JD, Blanchard C. Genetics of eosinophilic esophagitis. Dig Dis. 2014;32:22–9.

- Spergel JM. New genetic links in eosinophilic esophagitis. Genome Med. 2010;2:60.

- Noel RJ, Putnam PE, Rothenberg ME. Eosinophilic esophagitis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:940–1.

- Blanchard C, Wang N, Stringer KF, Mishra A, Fulkerson PC, Abonia JP, et al. Eotaxin-3 and a uniquely conserved geneexpression profile in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:536-47.

- Sherrill JD, Gao PS, Stucke EM, Blanchard C, Collins MH, Putnam PE, et al. Variants of thymic stromal lymphopoietin and its receptor associate with eosinophilic esophagitis. JAllergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:160–5.e3.

- Rothenberg ME, Spergel JM, Sherrill JD, Annaiah K, Martin LJ, Cianferoni A, et al. Common variants at 5q22 associate with pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Nat Genet. 2010;42:289–91.

- Sleiman PM, Wang ML, Cianferoni A, Aceves S, Gonsalves N, Nadeau K, et al. GWAS identifies four novel eosinophilic esophagitis loci. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5593.

- Hughes-Davies L, Huntsman D, Ruas M, Fuks F, Bye J, Chin SF, et al. EMSY links the BRCA2 pathway to sporadic breast and ovarian cancer. Cell. 2003;115:523–35.

- Ansel KM, Djuretic I, Tanasa B, Rao A. Regulation of Th2 differentiation and Il4 locus accessibility. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:607–56.

- Tamura K, Ohbayashi N, Maruta Y, Kanno E, Itoh T, Fukuda M. Varp is a novel Rab32/38-binding protein that regulates Tyrp1 trafficking in melanocytes. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:2900–8.

- Kottyan LC, Davis BP, Sherrill JD, Liu K, Rochman M, Kaufman K, et al. Genome-wide association analysis of eosinophilic esophagitis provides insight into the tissue specificity of this allergic disease. Nat Genet. 2014;46:895–900.

- Sperry SL, Crockett SD, Miller CB, Shaheen NJ, Dellon ES. Esophageal foreign-body impactions: epidemiology, time trends, and the impact of the increasing prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:985–91.

- Kidambi T, Toto E, Ho N, Taft T, Hirano I. Temporal trends in the relative prevalence of dysphagia etiologies from 1999-2009. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4335–41.

- Hruz P, Straumann A, Bussmann C, Heer P, Simon HU, Zwahlen M, et al; Swiss EoE study group. Escalating incidence of eosinophilic esophagitis: a 20-year prospective, populationbased study in Olten County, Switzerland. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:1349–50

- Soon IS, Butzner JD, Kaplan GG, deBruyn JC. Incidence and prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;57:72–80.

- Spergel JM, Book WM, Mays E, Song L, Shah SS, Talley NJ, et al. Variation in prevalence, diagnostic criteria, and initial management options for eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases in the United States. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52:300–6.

- Kapel RC, Miller JK, Torres C, Aksoy S, Lash R, Katzka DA. Eosinophilic esophagitis: a prevalent disease in the United States that affects all age groups. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1316–21.

- Franciosi JP, Tam V, Liacouras CA, Spergel JM. A case-control study of sociodemographic and geographic characteristics of 335 children with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:415–9.

- Sperry SL, Woosley JT, Shaheen NJ, Dellon ES. Influence of race and gender on the presentation of eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:215–21.

- Spergel JM, Brown-Whitehorn TF, Beausoleil JL, Franciosi J, Shuker M, Verma R, et al. 14 years of eosinophilic esophagitis: clinical features and prognosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48:30–6.

- Liacouras CA, Spergel JM, Ruchelli E, Verma R, Mascarenhas M, Semeao E, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: a 10-year experience in 381 children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:1198–206.

- Prasad GA, Talley NJ, Romero Y, Arora AS, Kryzer LA, Smyrk TC, et al. Prevalence and predictive factors of eosinophilic esophagitis in patients presenting with dysphagia: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2627–32.

- Dellon ES, Gibbs WB, Fritchie KJ, Rubinas TC, Wilson LA, Woosley JT, et al. Clinical, endoscopic, and histologic findings distinguish eosinophilic esophagitis from gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1305–13

- Desai TK, Stecevic V, Chang CH, Goldstein NS, Badizadegan K, Furuta GT. Association of eosinophilic inflammation with esophageal food impaction in adults. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:795–801.

- Kerlin P, Jones D, Remedios M, Campbell C. Prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in adults with food bolus obstruction of the esophagus. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:356–61.

- Veerappan GR, Perry JL, Duncan TJ, Baker TP, Maydonovitch C, Lake JM, et al. Prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in an adult population undergoing upper endoscopy: a prospective study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:420–6.

- Assa’ad AH, Putnam PE, Collins MH, Akers RM, Jameson SC, Kirby CL, et al. Pediatric patients with eosinophilic esophagitis:an 8-year follow-up. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:731–8.

- Chehade M, Aceves SS. Food allergy and eosinophilic esophagitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;10:231–7.

- Roy-Ghanta S, Larosa DF, Katzka DA. Atopic characteristics of adult patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:531–5.

- Foroutan M, Norouzi A, Molaei M, Mirbagheri SA, Irvani S, Sadeghi A, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in patients with refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:28–31.

- García-Compeán D, González González JA, Marrufo García CA, Flores Gutiérrez JP, Barboza Quintana O, Galindo Rodríguez G, et al. Prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in patients with refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms: A prospective study. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:204–8.

- Rodrigo S, Abboud G, Oh D, DeMeester SR, Hagen J, Lipham J, et al. High intraepithelial eosinophil counts in esophageal squamous epithelium are not specific for eosinophilic esophagitis in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:435–42.

- Kim HP, Vance RB, Shaheen NJ, Dellon ES. The prevalence and diagnostic utility of endoscopic features of eosinophilic esophagitis: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:988–96.

- Dellon ES, Aderoju A, Woosley JT, Sandler RS, Shaheen NJ. Variability in diagnostic criteria for eosinophilic esophagitis:a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2300–13.

- Peery AF, Cao H, Dominik R, Shaheen NJ, Dellon ES. Variable reliability of endoscopic findings with white-light and narrowband imaging for patients with suspected eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:475–80.

- Moy N, Heckman MG, Gonsalves N, Achem RS, Hirano I. Inter-observer agreement on endoscopic esophageal ûndings in eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:S236.

- Saffari H, Peterson KA, Fang JC, Teman C, Gleich GJ, Pease LF. Patchy eosinophil distributions in an esophagectomy specimen from a patient with eosinophilic esophagitis: Implications for endoscopic biopsy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:798–800.

- Dellon ES, Speck O, Woodward K, Woosley J, Shaheen NJ. The patchy nature of esophageal eosinophilia in eosinophilic esophagitis: insights from pathology samples from a clinical trial. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:S1129.

- Dellon ES, Gebhart JH, Higgins LL, Hathorn KE, Woosley JT, Shaheen NJ. The esophageal biopsy “pull” sign: a highly specific and treatment-responsive endoscopic finding in eosinophilic esophagitis (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:92–100.

- Gonsalves N, Policarpio-Nicolas M, Zhang Q, Rao MS, Hirano I. Histopathologic variability and endoscopic correlates in adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:313–9.

- Shah A, Kagalwalla AF, Gonsalves N, Melin-Aldana H, Li BU, Hirano I. Histopathologic variability in children with eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:716–21.

- Collins MH. Histopathologic features of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2008;18:59–71

- Odze RD. Pathology of eosinophilic esophagitis: what the clinician needs to know. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:485–90.

- Spechler SJ, Genta RM, Souza RF. Thoughts on the complex relationship between gastroesophageal reflux disease and eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1301–6.

- Ngo P, Furuta GT, Antonioli DA, Fox VL. Eosinophils in the esophagus—peptic or allergic eosinophilic esophagitis? Caseseries of three patients with esophageal eosinophilia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1666–70.

- Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Hirano I, Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Katzka DA; American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guideline: Evidenced based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:679–92

- Dranove JE, Horn DS, Davis MA, Kernek KM, Gupta SK. Predictors of response to proton pump inhibitor therapy among children with significant esophageal eosinophilia. J Pediatr. 2009;154:96–100.

- Sayej WN, Patel R, Baker RD, Tron E, Baker SS. Treatment with high-dose proton pump inhibitors helps distinguish eosinophilic esophagitis from noneosinophilic esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;49:393–9.

- Molina-Infante J, Ferrando-Lamana L, Ripoll C, Hernandez- Alonso M, Mateos JM, Fernandez-Bermejo M, et al. Esophageal eosinophilic infiltration responds to proton pump inhibition in most adults. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:110–7.

- Aceves SS, Newbury RO, Dohil MA, Bastian JF, Dohil R. A symptom scoring tool for identifying pediatric patients with eosinophilic esophagitis and correlating symptoms with inflammation. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;103:401–6

- von Arnim U, Wex T, Röhl FW, Neumann H, Küster D, Weigt J, et al. Identification of clinical and laboratory markers for predicting eosinophilic esophagitis in adults. Digestion. 2011;84:323–7.

- Mulder DJ, Hurlbut DJ, Noble AJ, Justinich CJ. Clinical features distinguish eosinophilic and reflux-induced esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;56:263–70.

- Dellon ES, Rusin S, Gebhart JH, Covey S, Speck O, Woodward K, et al. A Clinical Prediction Tool Identifies Cases of Eosinophilic Esophagitis Without Endoscopic Biopsy: Prospective Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1347–54.

- Schlag C, Miehlke S, Heiseke A, Brockow K, Krug A, von Arnim U, et al. Peripheral blood eosinophils and other non-invasive biomarkers can monitor treatment response in eosinophilic oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:1122–30.

- Straumann A. Eosinophilic esophagitis: indications for treatment. Dig Dis. 2014;32:110–3.

- Aceves SS, Bastian JF, Newbury RO, Dohil R. Oral viscous budesonide: a potential new therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis in children. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2271–9

- Konikoff MR, Noel RJ, Blanchard C, Kirby C, Jameson SC, Buckmeier BK, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebocontrolled trial of fluticasone propionate for pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1381–91

- Alexander JA, Jung KW, Arora AS, Enders F, Katzka DA, Kephardt GM, et al. Swallowed fluticasone improves histologic but not symptomatic response of adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:742–9.

- Butz BK, Wen T, Gleich GJ, Furuta GT, Spergel J, King E, et al. Efficacy, dose reduction, and resistance to high-dose fluticasone in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:324–33

- Schaefer ET, Fitzgerald JF, Molleston JP, Croffie JM, Pfefferkorn MD, Corkins MR, et al. Comparison of oral prednisone and topical fluticasone in the treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis: a randomized trial in children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:165–73.

- Peterson KA, Thomas KL, Hilden K, Emerson LL, Wills JC, Fang JC. Comparison of esomeprazole to aerosolized, swallowed fluticasone for eosinophilic esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1313–9.

- Moawad FJ, Veerappan GR, Dias JA, Baker TP, Maydonovitch CL, Wong RK. Randomized controlled trial comparing aerosolized swallowed fluticasone to esomeprazole for esophageal eosinophilia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:366–72.

- Dohil R, Newbury R, Fox L, Bastian J, Aceves S. Oral viscous budesonide is effective in children with eosinophilic esophagitis in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:418–29.

- Straumann A, Conus S, Degen L, Felder S, Kummer M, Engel H, et al. Budesonide is effective in adolescent and adult patients with active eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1526–37, 1537.

- Gupta SK, Collins MH, Lewis D Farber RH. Efficacy and safety of oral budesonide suspension (OBS) in pediatric subjects with eosinophilic esophagitis (EOE): results from the double-blind, placebo-controlled peer study. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:S179.

- Dellon ES, Sheikh A, Speck O, Woodward K, Whitlow AB, Hores JM, et al. Viscous topical is more effective than nebulized steroid therapy for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:321–4.

- Contreras EM, Gupta SK. Steroids in pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2014;43:345–56.

- Albert D, Heifert TA, Min SB, Maydonovitch CL, Baker TP, Chen YJ, et al. Comparisons of Fluticasone to Budesonide in the Treatment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2016 Apr 19. [Epub ahead of print]

- Lee JJ, Fried AJ, Hait E, Yen EH, Perkins JM, Rubinstein E. Topical inhaled ciclesonide for treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:1011.

- Bergquist H, Larsson H, Johansson L, Bove M. Dysphagia and quality of life may improve with mometasone treatment in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis: a pilot study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145:551–6.

- Tan ND, Xiao YL, Chen MH. Steroids therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis: Systematic review and meta analysis. J Dig Dis. 2015;16:431–42.

- Murali AR, Gupta A, Attar BM, Ravi V, Koduru P. Topical steroids in Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Placebo Controlled Randomized Clinical Trials. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Dec 23.

- Harel S, Hursh BE, Chan ES, Avinashi V, Panagiotopoulos C. Adrenal insufficiency exists for both swallowed budesonide and fluticasone propionate in the treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis. J Pediatr. 2016 Mar 19.

- Golekoh MC, Hornung LN, Mukkada VA, Khoury JC, Putnam PE, Backeljauw PF. Adrenal Insufficiency after Chronic Swallowed Glucocorticoid Therapy for Eosinophilic Esophagitis. J Pediatr. 2016;170:240–5.

- Philla KQ, Min SB, Hefner JN, Howard RS, Reinhardt BJ, Nazareno LG, et al. Swallowed glucocorticoid therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis in children does not suppress adrenal function. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2015;28:1101–6.

- Attwood SE, Lewis CJ, Bronder CS, Morris CD, Armstrong GR, Whittam J. Eosinophilic oesophagitis: a novel treatment using Montelukast. Gut. 2003;52:181–5.

- Lucendo AJ, De Rezende LC, Jiménez-Contreras S, Yagüe- Compadre JL, González-Cervera J, Mota-Huertas T, et al. Montelukast was inefficient in maintaining steroid-induced remission in adult eosinophilic esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:3551–8.

- Abonia JP, Blanchard C, Butz BB, Rainey HF, Collins MH, Stringer K, et al. Involvement of mast cells in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:140–9.

- Netzer P, Gschossmann JM, Straumann A, Sendensky A, Weimann R, Schoepfer AM. Corticosteroid-dependent eosinophilic oesophagitis: azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine can induce and maintain long-term remission. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19:865–9.

- Spergel JM, Rothenberg ME, Collins MH, Furuta GT, Markowitz JE, Fuchs G 3rd, et al. Reslizumab in children and adolescents with eosinophilic esophagitis: results of a doubleblind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:456–63.

- Stein ML, Collins MH, Villanueva JM, Kushner JP, Putnam PE, Buckmeier BK, et al. Anti-IL-5 (mepolizumab) therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:1312–9.

- Assa’ad AH, Gupta SK, Collins MH, Thomson M, Heath AT, Smith DA, et al. An antibody against IL-5 reduces numbers of esophageal intraepithelial eosinophils in children with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1593–604.

- Straumann A, Conus S, Grzonka P, Kita H, Kephart G, Bussmann C, et al. Anti-interleukin-5 antibody treatment (mepolizumab) in active eosinophilic oesophagitis: a randomised, placebocontrolled, double-blind trial. Gut. 2010;59:21–30

- Loizou D, Enav B, Komlodi-Pasztor E, Hider P, Kim-Chang J, Noonan L, et al. A pilot study of omalizumab in eosinophilic esophagitis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0113483.

- Straumann A, Bussmann C, Conus S, Beglinger C, Simon HU. Anti-TNF-alpha (infliximab) therapy for severe adult eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:425–7.

- Rothenberg ME. Biology and treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1238–49.

- Kelly KJ, Lazenby AJ, Rowe PC, Yardley JH, Perman JA, Sampson HA. Eosinophilic esophagitis attributed to gastroesophageal reflux: improvement with an amino acid-based formula. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:1503–12.

- Markowitz JE, Spergel JM, Ruchelli E, Liacouras CA. Elemental diet is an effective treatment for eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adolescents. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:777–82.

- Peterson K, Clayton F, Vinson LA, Fang JC, Boynton KK, Gleich GJ et al. Utility of an elemental diet in adult eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:AB1080.

- Lucendo AJ, Arias A, Gonzalez-Cervera J, et al. Efficacy of six food elimination diet in adult eosinophilic oesophagitis: a prospective study. Gut. 2011;60:A42.

- Kagalwalla AF, Sentongo TA, Ritz S, Hess T, Nelson SP,Emerick KM, et al. Effect of six-food elimination diet on clinical and histologic outcomes in eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1097–102.

- Gonsalves N, Yang GY, Doerfler B, Ritz S, Ditto AM, HiranoI. Elimination diet effectively treats eosinophilic esophagitis in adults; food reintroduction identifies causative factors. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1451–9.

- Spergel JM, Andrews T, Brown-Whitehorn TF, Beausoleil JL, Liacouras CA. Treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis with specific food elimination diet directed by a combination of skinprick and patch tests. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005;95:336–43.

- Spergel JM, Brown-Whitehorn T, Beausoleil JL, Shuker M, Liacouras CA. Predictive values for skin prick test and atopy patch test for eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:509–11.

- Spergel JM, Beausoleil JL, Mascarenhas M, Liacouras CA. The use of skin prick tests and patch tests to identify causative foods in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:363–8.

- Molina-Infante J, Martin-Noguerol E, Rodriguez GV, Hernandez Alonso M, Gonzalez-Santiago JM, Martinez-Alcala C et al. Efûcacy of elimination diet based on food sensitization skin testing for adult eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:S1128.

- Arias A, González-Cervera J, Tenias JM, Lucendo AJ. Efficacy of dietary interventions for inducing histologic remission in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1639–48.

- Straumann A, Conus S, Degen L, Frei C, Bussmann C, Beglinger C, et al. Long-term budesonide maintenance treatment is partially effective for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:400–9.

- Lucendo AJ, Arias Á, González-Cervera J, Yagüe-Compadre JL, Guagnozzi D, Angueira T, et al. Empiric 6-food elimination diet induced and maintained prolonged remission in patients with adult eosinophilic esophagitis: a prospective study on the food cause of the disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:797–804.

- Schoepfer AM, Gschossmann J, Scheurer U, Seibold F, Straumann A. Esophageal strictures in adult eosinophilic esophagitis: dilation is an effective and safe alternative after failure of topical corticosteroids. Endoscopy. 2008;40:161–4.

- Schoepfer AM, Gonsalves N, Bussmann C, Conus S, Simon HU, Straumann A, et al. Esophageal dilation in eosinophilic esophagitis: effectiveness, safety, and impact on the underlying inflammation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1062–70.

- Kavitt RT, Ates F, Slaughter JC, Higginbotham T, Shepherd BD, Sumner EL, et al. Randomized controlled trial comparing esophageal dilation to no dilation among adults with esophageal eosinophilia and dysphagia. Dis Esophagus. 2015 Jul 30.

- Cohen MS, Kaufman AB, Palazzo JP, Nevin D, Dimarino AJ Jr, Cohen S. An audit of endoscopic complications in adult eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1149–53.

- Jacobs JW Jr, Spechler SJ. A systematic review of the risk of perforation during esophageal dilation for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1512–5.

- Bohm ME, Richter JE. Review article: oesophageal dilation in adults with eosinophilic oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:748–57.

- Rothenberg ME, Wen T, Greenberg A, Alpan O, Enav B, Hirano I, et al. Intravenous anti-IL-13 mAb QAX576 for the treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:500–7.

- Straumann A, Hoesli S, Bussmann Ch, Stuck M, Perkins M, Collins LP, et al. Anti-eosinophil activity and clinical efficacy of the CRTH2 antagonist OC000459 in eosinophilic esophagitis. Allergy. 2013;68:375–85.

|

|

|

|

|

|