|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Original Articles |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

H. pylori, histology, gastritis, eradication therapy, sensity. |

|

|

Dharmesh K. Shah1, Samit S. Jain2, Ashok Mohite1, Anjali D. Amarapurkar1, Q.Q. Contractor1, Pravin M. Rathi1

Department of Gastroenterology1

and Pathology2,

T.N.M.C, B.Y.L,

Nair Hospital,

Mumbai-400008, India

Corresponding Author:

Dr Pravin M Rathi

Email: rathipmpp@gmail.com

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.261

Abstract

Introduction: Helicobacter pylori (H.pylori) infection causes chronic gastritis and is a major risk factor for duodenal and gastric ulceration, gastricadenocarcinoma, and primary gastric lymphoma. Increased gastric bacterial density may lead to increased levels of inflammation and epithelial injury.

Aims and objectives: 1) To study the effect of H. pylori density by histological changes in stomach.2) To study the effect of H.pylori density on the efficacy of standard triple drug eradication treatment. 3) To study the effect of H. pylori density on the complication related to H.pylori.

Material and methods: All the patients visiting gastroenterology OPD with the symptoms of dyspepsia not responding to proton pump inhibitor or having alarm symptoms were subjected to upper GI endoscopy and biopsy. If H.pylori was present they were included in the study.The patients were given standard 14 day triple antibiotic combination for H.pylori eradication. H.pylori eradication was confirmed by urea breath test after six weeks of completion of treatment.

Results: Out of 250 patients screened, 120 patients enrolled in the study.On clinical history 41.5% patients had symptoms of heart burn where as 63.3% patients had dyspeptic symptoms. Success rate of anti H. pylori triple drug therapy was 80%. Rate of eradication was significantly lower among the patients with higher H.pylori density (p < 0.05) on histopathology by Sydney classification. Duodenal ulcer, Gastric ulcer and gastric erosion were noted in higher frequencies among the patients with higher H.pylori density (p < 0.05).

Conclusion: H.pylori density by histopathology correlates with the complication related to H. pylori i.e. duodenal ulcer, reflux esophagitis and antral erosions. It also correlates with the success of the standard triple drug eradication treatment.

|

48uep6bbphidvals|720 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection causes chronic gastritis and is a major risk factor for duodenal and gastric ulceration (DU & GU), gastric adenocarcinoma, and primary gastric lymphoma.In most patients H. pylori does not cause symptoms and the infection often persists without any clinically evident disease.[1,2] It has been identified in 90-95 % of patients with duodenal ulcer and 60- 80 % of patients with gastric ulcer.

Strong evidence has shown that eradication of H. pylori infection can cure peptic ulcer disease. Increased gastric bacterial density leads to increased mucosal neutrophil and lymphocyte density [3,4] and duodenal ulceration.[5] Bacterial density in these reports were based on histology, semiquantitative and subjective scoringsystems. Some of the results were conflicting.[6] Histological assessment of the distribution and density of H. pylori in the stomach has suggested that there may be greater colonisation of the gastric antrum in duodenal ulcer patients.[7]

Commonly used eradication therapy for H. pylori is proton pump inhibitor (PPI)-based triple therapy (a PPI and two different anti-microbials), which can assure rapid symptom relief, improve ulcer healing, and reduce ulcer recurrence.[8-10] Patient compliance and antibiotic resistance are currently regarded as the major causes of eradication failure.[11] Several researchers have also revealed that high antral density of H. pylori may increase the rate of ulcer recurrence and be related with low eradication rate after triple therapy.[12-14] Intra-gastric bacterial load might be another factor reducing the success of eradication therapy.[14]

We investigated the association of H. pylori density in the stomach with the efficacy of eradication therapy, ulcer healing and symptomatic improvement in patients with dyspepsia. We also studied the relationship of histopathological changes in the stomach with H. Pylori density.

Materials and methods

Patients visiting the gastroenterology clinic at B. Y. L. Nair Charitable Hospital with symptoms of dyspepsia or reflux not responding to proton pump inhibitors or demonstrating‘alarm’symptoms were screened for the study. We excluded those under 18 years, those who had history of NSAID intake in the previous[4] weeks, antibiotic treatment in the previous 2, active smokers, pregnant women, immune-compromised patients, and patients with history of gastric surgery and previous attempts to eradicate H. pylori.

Institutional ethics committee permission was obtained before initiation.Written informed consent of each patient was obtained.Patients who met inclusion and exclusion criteria were subjected to upper GI endoscopy with biopsy. A single expert pathologist studied all the biopsies. All positive findings (antral erythema, gastric ulcer, duodenal ulcer, Barrett’s esophagus, reflux esophagitis)were noted during endoscopic examination.

Patients with biopsy showing H. pylori were enrolled in the study. A detailed clinical history including data pertaining to epidemiological factors like age, parity, residential address and occupation was recorded.Glasgow Dyspepsia Severity Score was calculated in every patient using standard questionnaire at the beginning of the study and 4 weeks after completion of H. pylori eradication treatment.[15]

Endoscopic procedure: At upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, active peptic ulceration was defined as a circumscribed break in the mucosa, measuring at least 0.5 cm in any dimension. Activeerosion was defined as a circumscribed break in the mucosa not fulfilling these criteria. Gastric biopsy specimens weighing 3-10 microgramswere obtained, using biopsy forceps. Two gastric antral, twogastric corpus biopsies and a biopsy from incisura were obtained from similar topographical sites at each endoscopy.

Histological methods: Adjacent paraffin sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin and modifiedGiemsa stain, and then examined by a single experienced histopathologist unaware of the patient’s clinical diagnosis. Bacterial density was quantified in the Giemsa sections by counting Helicobacter-like organisms on the mucosal surface and in the foveolae and dividing by the number of high-power fields (hpf) presented by the mucosal surface. Other histologic features were graded using the hematoxylin-eosin section. Features scored were neutrophilic, lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltration, epithelial degeneration (irregular luminal cell borders, nuclear pyknosis), cytoplasmic eosinophilia, mucus depletion, and epithelial erosion. The version of the visual analogue scale in the updated Sydney system was used to grade the density of H. pylori (4 grades: normal, no bacteria; mild, focal few bacteria; moderate, more bacteria in several areas; and severe, abundance of bacteria in most glands). If the density varied, the highest grade of density in the specimens was selected. The severity of gastritis in the same specimen was also scored 0-3, corresponding to nil, mild, moderate, and severe mononuclear cell infiltration. In order to improve the assessment of minor degrees of alteration, a detailed histopathological classification was used, described by Chen XY et al.[16]

Astandard 14-day oral triple therapy for H. pylori eradication was given to all patients. Patients received twice daily amoxicillin 1000 mg, clarithromycin 500 mg and pantoprazole 40 mg. Eradication of H. pylori infection was defined as negative results on Urea Breath Test (UBT) and histology at 4 weeks after the cessation of therapy or negative results on two UBTs at 4 weeks after the cessation of therapy.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were compared by means of Student’s test for unpaired data in two group comparison. Chi-square test or Fisher’s correction were used to evaluate the differences for categorical variables. The one-way analysis of variance was primarily intended to compare the means. For all tests, value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed by SPSS software (Version 16).

Results

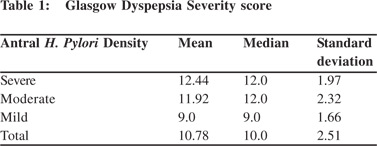

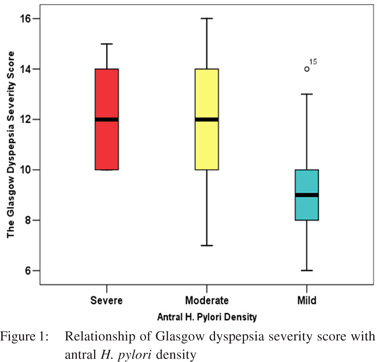

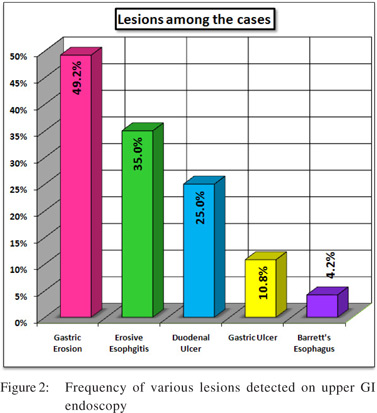

Out of 250 patients screened 120 patients met the inclusion criteria and were enrolled in the study.Mean age was 31.22 ± 6.53 years and 55% were male.On clinical history 44 (26.7%) patients had predominant symptoms of heartburn where as 76 (63.3%) patients had predominant dyspeptic symptoms.There was no significant difference in the mean Glasgow Dyspepsia Severity score in patients having various severity of antral H. pylori density calculated with one-way ANOVA.(Table 1 and Figure 1) On upper GI endoscopy, various lesions noted were gastric erosion (49.2%), erosive esophagitis (35%),DU (25 %), GU (19.2 %) and Barrett’s esophagus (4.2%) (Figure 2).34.2% of patients withonly dyspeptic symptoms had erosive esophagitis with no symptoms of reflux. Only 43.1 % of patients with reflux symptoms had erosive esophagitis(p > 0.05). Similarly only 38.2 % of the patients of DU (p value =0.28) and 36.7 % of the patients with GU (p value =0.26) had reflux symptoms. So reflux symptoms are a poor predictor of reflux esophagitis, DU and GU on upper GI endoscopy.

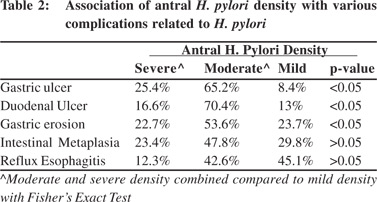

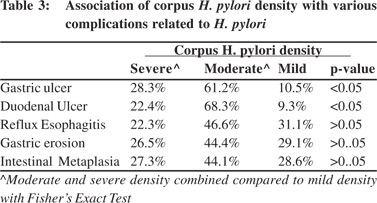

Amongst the patients with reflux symptoms, 31 (70.45 %) had moderate or severe antral H. pylori density on histology and 13 (29.54 %) had mild H. pylori density(p <.005). H. pylori density in antrum and corpus was correlated with the various complications related to H. pylori (Tables 2 and 3).

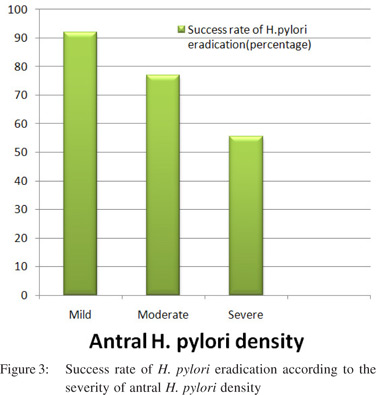

Significantly higher percentage of patients with DU (87%), GU (91.6%) and gastric erosion(72.3%) had moderate or severe antral H. pylori density (p< 0.05). Similarly a significantly higher percentage of patients with DU (90.7%), GU (89.5%) had moderate or severe corpus H. pylori density (p< 0.05). Patients with Barrett’s esophagus were too few for statistical analysis. Eradication rate with triple therapy was 80 %. Success rate was significantly lower in patients with severe (10/18 patients, 55.55%) and moderate (40/52 patients, 76.92%) antral H. pylori density compared to those with mild density (46/50 patients, 92% - p < 0.05, Figure 3) Symptomatic improvement after H. pylori eradication was seenin 60% of the patients. Rate of symptomatic improvement was higher in patients with reflux symptoms (74%) than dyspeptic patients (51.4% - p< 0.05).

Discussion

There was no statistically significant difference in the mean Glasgow Dyspepsia Severity score in patients with varying severity of antral H. Pylori density. This suggests that symptomsonly poorly correlate with H. pylori density and thus to the severity of inflammation in the stomach. Similarly, only 38.2 % of patients with duodenal ulcer, and 43.1 % of patients with erosive esophagitis suffered symptoms of reflux. Thus, symptoms of reflux disease poorly correlate with reflux-related complications.

Significantly higher percentage of patients with DU (87%) had moderate or severe antral as well as corpus H. pylori density (p < 0.05). Also, significantly higher percentage of patients with GU (91.6%) had moderate or severe antral and corpus H. pylori density (p< 0.05). These results are not in agreement with some of the previous studies, which concluded that DU disease is associated with an antral predominant (or corpus sparing) pattern of gastritis. The average density of H.pylori in the antrum of DU patients was greater than in the antrum of gastritis patients.[7,17]

Regurgitation of acidic gastric contents into the esophagus is a key mechanism of reflux-esophagitis secondary to gastroesophageal reflux disease.[18] H. pylori infection is one of the most important factors contributing to the development of gastritis and atrophy thatalso involves the gastric corpus.[19]

It has been reported that H.pylori infection was less prevalent and atrophic gastritis less severe in patients with erosive esophagitis than in those without esophagitis.[20,21] H.pylori infection suppresses the development of reflux esophagitis by inducing atrophic gastritis that results in gastric

hyposecretion.[22] In our study we recordeda very low incidence of Barrett’s esophagus (4.16 %) compared to the published western literature which ranges from 6%-15%. This finding might be due to corpus predominant gastritis. However, prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus amongst Indians ranges from 6% to 23%in studies done in Indian patients with refluxrelated symptoms.[23,24]

As our study is based on histopathology, significant interobserver variation can be expected whilst interpretingthe results. However, the grading of H.pylori according to modified Sydney classification has good reproducibility, with k value of 0.74 reported by Andrew et al and 0.90 reported by El-Zimaity et al.[25,26] So, H&E was an adequate stain for the detection and grading of H pylori with good inter-observer agreement. There is also adequateinter-observer agreement for intestinal metaplasia with k-values varying from0.54 (CI: 0.31- 0.77) in the study by Tepes et al[27] to 0.73 in the study by Andrew et al.[25] The H&E stain has been the standard basis for recognition of intestinal metaplasia.[28]

In our study, the success rate with triple drug therapy was 80 % which is similar to that previously reported. Treatment success rate was significantly lower in patients with moderate to severe H. pylori density as compared to those with mild density. Thesuccess rate was only 55.55% in patients with severe H. pylori density. Patients with severe H. pylori density possibly need more effective treatment like sequential therapy to improve the eradication rate.[29-31] Culture and antibiotic sensitivity can also be done in patients with failure of H. pylori eradication.

The role of H.pylori eradication in non-ulcer dyspepsia is less clear. Approximately half the patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia are infected with H. pylori.[32] Whether eradication of H. pylori infection improves the symptoms of non-ulcer dyspepsia is a matter of debate. In the last few years, several large, randomized, double blind, controlled trials were performed with conflicting results.[33-39] Symptomatic improvement after H. pylori eradication was found in 60% of patients. The rate of symptomatic improvement was higher in patients with reflux symptoms (74%) than dyspeptic patients (51.4%) (p< 0.05). More than half the patients with dyspeptic symptoms showedimprovement. Hence patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia should be tested and treated for H. pylori infection. There are some limitations inthisstudy. We estimated H. pylori density by histopathology and not by PCR-based quantitative culture method which is the gold standard. It is costly and rarely done in routine clinical practice. We did not evaluate the various virulence factors like cag pathogenicity island (CagA) and the vacuolatingcytotoxin (VacA) because of cost constraint.These factors may have an impact on various complications related to H. pylori. Long-term follow up of the patients for symptom relief, and recurrence of H. pylori infection was also not studied.

In conclusion, H. pylori density by histopathology correlates with the complications related to H. pylori such as duodenal ulcer and gastric ulcer. It also correlates with the success of the standard triple drug eradication therapy for H. pylori. So, patients with higher H. pylori density should be checkedfor H. pylori eradication at6 weeks following completion of treatment.

References

- Marshall BJ Warren JR. Unidentified curved bacilli on gastric epithelium in active chronic gastritis. Lancet. 1983;8336:1273–5.

- Graham DY SJ. Helicobacter pylori. In: Feldman M, ed. Sleisenger and Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease, 8th edn. Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, 2006;1049–68.

- Bayerdorffer E, Lehn N, Hatz R, Mannes GA, Oertel H, Sauerbruch T, et al. Difference in expression of Helicobacter pylori gastritis in antrum and body. Gastroenterology 1992;102:1575–82.

- Satoh K, Kimura K, Yoshida Y, Kasano T, Kihira K, Taniguchi Y.A topographical relationship between Helicobacter pylori and gastritis: quantitative assessment of Helicobacter pylori in the gastric mucosa. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:285–91.

- Alam K, Schubert TT, Bologna SD, Ma CM. Increased density of Helicobacter pylori on antral biopsy is associated with severity of acute and chronic inflammation and likelihood of duodenal ulceration. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:424–8.

- Langdale-Brown B, Haqqani MT. Acridine orange fluorescence, Campylobacter pylori, and chronic gastritis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1990;25:127–33.

- Khulusi S, Mendall MA, Patel P, Levi J, Badve S, Northfield TC. Helicobacter pylori infection densityand gastric inflammation in duodenal ulcer and non-ulcer subjects. Gut. 1995;37:319–24.

- AsakaM, Sugiyama T,KatoM, Satoh K, Kuwayama H, Fukuda Y, et al. Amulticenter, double-blind study on triple therapy with lansoprazole, amoxicillin and clarithromycin for eradication of Helicobacter pylori in Japanesepeptic ulcer patients. Helicobacter 2001;6:254–61.

- Penston JG. Helicobacter pylori eradication: understandable caution but no excuse for inertia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1994;8:369–89.

- Logan RP, Bardhan KD, Celestin LR, Theodossi A, Palmer KR, Reed PI, et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori and prevention of recurrence of duodenal ulcer: a randomized double-blind, multicentre trial of omeprazole with or without clarithromycin. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9:417–23.

- Maconi G, Parente F, Russo A, Vago L, Imbesi V, Porro GB. Do some patients with Helicobacter pylori infection benefit from an extension to 2 weeks of a proton pump inhibitor-based triple eradication therapy? Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:359–66.

- Sheu BS, Yang HB, Su IJ, Shiesh SC, Chi CH, Lin XZ. Bacterial density of Helicobacter pylori predicts the success of triple therapy in bleeding duodenal ulcer. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:683–8.

- Moshkowitz M, Konikoff FM, Peled Y, Santo M, Hallak A, Bujanover Y, at al. High Helicobacter pylori numbers are associated with low eradication rate after triple therapy. Gut. 1995;36:845–7.

- Perri F, Clemente R, Festa V, Quitadamo M, Conoscitore P, Niro G, et al. Relationship between the results of pre-treatment urea breath test and efficacy of eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection. Ital J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1998;30:146–50.

- El-Omar EM, Banerjee S, Wirz A, McColl KEL. The Glasgow Dyspepsia Severity Score—a tool for the global measurement of dyspepsia. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;8:967–71.

- Chen XY, van der Hulst RW, Bruno MJ, van der Ende A, Xiao SD, Tytgat GN, et al.Interobserver variation in the histopathological scoring of Helicobacter pylori related gastritis. J Clin Pathol. 1999;52:612–5.

- Yamaoka Y, Kodama T, Kita M, Imanishi J, Kashima K, Graham DY. Relation between clinical presentation, Helicobacter pylori density, interleukin 1beta and 8 production, and cagA status. Gut. 1999;45:804–11.

- Dodds WJ, Dent J, Hogan WJ, Helm JF, Hauser R, Patel GK, etal.Mechanisms of gastroenterologeal reflux in patients with reflux esophagitis. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:1547–2.

- Kohli Y, Kato T, Iwaki M, et al. Endoscopic diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori distribution in gastric mucosa of patients with chronic gastritis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1993;5:127–31.

- Koike T, Ohara S, Sekine H, Iijima K, Kato K, Shimosegawa T, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection inhibits reflux esophagitis by inducing atrophic gastritis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3468–72.

- Mihara M, Haruma K, Kamada T, et al. Low prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with reflux esophagitis. Gut 1996;39:A94.

- Bock OAA, Richards WCD, Witts LJ. The relationship between acid secretion after augmented histamine stimulation and the histology of gastric mucosa. Gut 1963;4:112–4.

- Punia RS, Arya S, Mohan H, Duseja A, Bal A. Spectrum of clinico-pathological changes in Barrett oesophagus. J Assoc Physicians India. 2006;54:187–9.

- Dhawan PS, Alvares JF, Vora IM, Joseph TK, Bhatia SJ, Amarapurkar AD, et al. Prevalence of short segments of specialized columnar epithelium in distal esophagus: association with gastroesophageal reflux. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2001;20:144–7.

- Andrew A,Wyatt JI, DixonMF. Observer variation in the assessment of chronic gastritis according to the Sydney system.Histopathol. 1994;25:317–22.

- El-Zimaity HM, Graham DY, al-Assi MT, Malaty H, Karttunen TJ, Graham DP, Huberman RM, Genta RM. Interobserver variation in the histopathological assessment of Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Hum Pathol. 1996;27:35–41.

- Tepes B, Ferlan-Marolt V, Jutersek A, Kaucic B, Zaletel-Kragelj L. Interobserver agreement in the assessment of gastritis reversibility after Helicobacter pylori eradication. Histopathology. 1999;34:124–33.

- Segura DI, Montero C. Histochemical characterization of different types of intestinal metaplasia in gastric mucosa. Cancer. 1983;52:498–503.

- Vaira, A. Zullo, N. Vakil. Gatta L, Ricci C, Perna F, etalSequential therapy versus standard triple-drug therapy forHelicobacter pylori eradication: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:556–63.

- Gatta L, Vakil N, Leandro G, di Mario F, Vaira D. Sequential therapy or triple therapy forHelicobacter pylori infection: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in adults and children. Am J of Gastroenterol. 2009;104:3069–79.

- Hsu PI, Wu DC, Wu JY, Graham DY. Is there a benefit to extending the duration ofHelicobacter pylori sequential therapy to 14 days? Helicobacter. 2011;16:146–52.

- Pantoflickova D, Blum AL, Koelz HR. Helicobacter pylori and dyspepsia: A real causal link? Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol. 1998;12:503–32.

- Blum AL, Talley NJ, O’Morain C, van Zanten SV, Labenz J, Stolte M, et al. Lack of effect of treating Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with nonulcer dyspepsia. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1875–81.

- McColl K, Murray L, El Omar E, Dickson A, El-Nujumi A, Wirz A, et al. Symptomatic benefit from eradicating Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with nonulcer dyspepsia. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1869–74.

- Talley NJ, Janssens J, Lauritsen K, Rácz I, Bolling-Sternevald E. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori in functional dyspepsia: randomized double blind placebo controlled trial with 12 months’ follow up. BMJ. 1999;318:833–7.

- Talley NJ, Vakil N, Ballard II ED, Fennerty MB. Absence of benefit of eradicating Helicobacter pylori in patient with nonulcer dyspepsia. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1106–11.

- Miwa H, Hirai S, Nagahara A, Murai T, Nishira T, Kikuchi S,et al. Cure of Helicobacter pylori infection does not improve symptoms in non-ulcer dyspepsia patients—a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:317–24.

- Froehlich F, Gonvers JJ, Wietlisbach V, Burnand B, Hildebrand P, Schneider C, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication treatment does not benefit patients with nonulcer dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2329–36.

- Bruley Des Varannes S, Flejou JF, Colin R, Zaïm M, Meunier A, Bidaut-Mazel C.There are some benefits for eradicating Helicobacter pylori in patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001;15:1177–85.

|

|

|

|

|

|