|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Quarterly Reviews |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

Inflammatory bowel disease, immuno-modulator, large intestine, infliximab adalumimab. |

|

|

fluoxetine alcohol headache fluoxetine alcohol blackout link

Department of Gastroenterology

Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate Institute

of Medical Sciences

Raebareli Road

Lucknow 226014

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Uday C Ghoshal

Email: udayghoshal@yahoo.co.in

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.258

Abstract

Ulcerative colitis (UC) results from exaggerated immune response to gut flora in genetically predisposed individuals. Acute exacerbation of UC occurs in 12-58% of patients. About a fifth of these patients do not respond to intra-venous glucocorticoids, which is the standard treatment of this condition. Earlier, patients failing to respond to intra-venous glucocorticoids were treated with colectomy with its consequent disadvantages, such as low preference by the patients, need for surgical expertise, complications and even potential fatal outcome.

However, currently these patients are quite effectively managed by immunomodulator treatment such as cyclosporin and biologicals. Since tumor necrosis factor a (TNF-a) is the major proinflammatory cytokine involved in the pathogenesis of IBD, monoclonal anti-TNF antibody, such as infliximab, has been studied most in management of IBD, including UC. This paper reviews the current data on biologicals in management of acute UC.

|

48uep6bbphidvals|717 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a type of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) characterized by chronic inflammation localized to a part or whole of the colon, generally starting at the rectum and extending a variable distance over the proximal colon. 12-58% of patients with UC present with attacks of acute episodes.[1-3] The natural history of UC is variable;[4,5] in most patients, the initial exacerbations can be easily controlled by glucocorticoids, and the subsequent attacks can be prevented through continued use of aminosalicylates.[2,6] However, about a fifth of the exacerbations fail to remit with intravenous glucocorticoids.[6] In the past, these patients used to be treated by multi-stage surgical options culminating in proctocolectomy and ileo-anal anastomosis.[7,8] However, surgical treatment has inherent problems such as low patient preference, need for surgical expertise, complications and even potential fatality.[9,10] Hence, a search for alternative non-surgical options to treat such patients is warranted.

Since UC results from an exaggerated immune response to the gut flora, immuno-suppression is an effective method to treat this disease. Immunomodulators are used in these patients with an aim to control active imflammation, maintain remission and to withdraw corticosteroids.[11] The immonomodulators that have been used in the treatment of UC include azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, cyclosporin infliximab and adalumimab.[11] The latter group of drugs used for the treatment of IBD is called biological.

Of the various immunomodulators, azathioprine and 6- mercaptopurine work so slowly that these are used only in the maintenance of remission in patients with steroid-dependent UC.[12] In contrast, cyclosporin and infliximab have been used successfully to induce remission in patients with acute episodes not responding to intravenous corticosteroid over a 5 to 7 day period.[13] In an initial pivotal study by Lichtiger et al on 20 steroid refractory acute severe UC, 9/11 (82%) patients randomized to intravenous cyclosporin responded;[14] in contrast, none of the 5 patients randomized to placebo responded. However, all 5 patients in the placebo group who were crossed-over to cyclosporin did so.[14]Cyclosporin was initially criticized as most of the responding patients needed colectomy in the long-run.[15] In subsequent studies, however, cyclosporin was used as a bridge to maintenance therapy with azathioprine.[16] This strategy helped in avoiding colectomy in more than 80% patients on long-term follow-up after achieving initial response to cyclosporin.[17] Cyclosporin has been criticized for its narrow therapeutic window due to multiple adverse effects and need for stringent blood level maintenance in a specific range.[18]

Biological agents are the latest addition in the therapeutic armamentarium against IBD.[19] Their efficacy in the treatment of Crohn’s disease (CD) has been fairly well established, however, their role in the management of UC has been studied only recently. We will briefly review biologicals, particularly infliximab, in relation to management of acute severe UC.

The role of biologicals resulted from a better understanding of the pathogenesis of this disease especially the inflammatory mediators involved in it. Luminal antigens are thought to initiate the inflammatory cascade in IBD in genetically predisposed patients.[20] These antigens first bind to inflammatory cells present in the gut mucosa and activate them. Subsequently clonal proliferation and differentiation occur, which lead to pronounced infiltration into the lamina propria of innate and adaptive immune cells. Then these cells secrete a variety of cytokines like TNF-a, IL-1a, interferonã and cytokines of IL23- Th17 pathway.[20] Increased levels of TNF-a have been demonstrated locally as well as in the blood of patients with active IBD. It binds to trans-membrane TNF-a receptors resulting in intracellular signaling of nuclear factor kb (NFkb) which in turn stimulates the production of other potent inflammatory cytokines including TNF-a itself. TNF-a also leads to up-regulation of adhesion molecules which helps in recruiting more and more inflammatory cells from the circulation.

Neo-vascularization is also enhanced in the inflamed tissue. Other functions of TNF-a include activation of the coagulation cascade, inducing edema, taking part in granuloma formation and influencing apoptosis of target cells. Tumor necrosis factor-a is the key inflammatory mediator in IBD and therefore

most of the biologicals are targeted towards it. Infliximab, adalimumab and cetrolizumab are the most commonly used anti TNF agents for IBD.

Since UC is associated with over-expression of proinflammatory cytokines and under-expression of antiinflammatory cytokines, the biological agents aim to normalize this imbalance.20 Infliximab binds to free as well as membrane bound TNF. The initial use of murine monoclonal antibody was limited by its immunogenicity in humans. Genetic engineering was successful in constructing a partially human antibody that retained the high binding affinity of the mouse antibody, and increased the efficacy by lengthening the halflife and reducing the immunogenicity. ‘Chimeric’ antibodies, such as infliximab, retain the entire variable domain from the murine antibody, attached to the human constant (C) region, and are therefore approximately 25% mouse and 75% human.[21]

However, use of chimeric molecule is associated with development of anti-infliximab antibody on repeated injection resulting in loss of therapeutic response.[21] Humanized antibody such as adalumimab is substantially less immunogenic than pure murine and chimeric antibodies.

Infliximab binds strongly to soluble and trans-membrane TNF. Although this paradoxically prolongs the half-life of TNF, the TNF to which it is bound is rendered biologically inactive. In vitro, the trans-membrane binding leads to complement activation and antibody dependent cell cytotoxicity of activated CD4+ T-cells and macrophages. Administration of infliximab results in a reduction in lamina propria CD4+ and CD 8+ T-cells, and CD68+ monocytes. There is a parallel reduction in mucosal Th1 cytokine production, and reduced levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1 and IL-6, and adhesion molecules E-selectin and ICAM-l. In addition, it has been shown in rheumatoid arthritis, that infliximab causes a decrease in the serum levels of matrix metalloproteinase 1 and 3. These enzymes are also thought to be responsible for tissue destruction in inflammatory bowel disease. A recent report suggested that infliximab can induce apoptosis in stimulated T-cells in vitro. It has been postulated that the loss of activated T-cell clones accounts for the prolongation of clinical response beyond the half-life of the drug (10-14 days).[21]

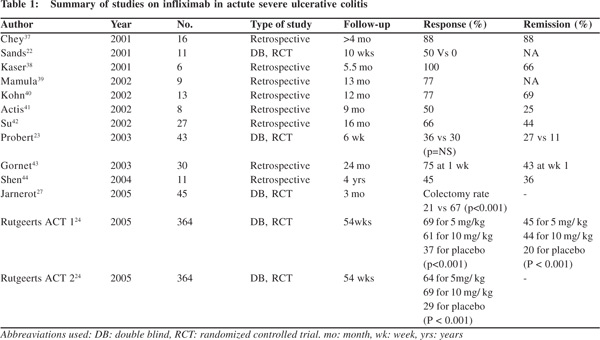

The initial few trials of infliximab in UC gave conflicting results (Table 1). In the small placebo-controlled study by Sands et al,[22] four of eight patients (50%) treated with infliximab responded at 2 weeks in contrast to none of the three placebotreated patients. In the study by Probert et al[23] remission was achieved with infliximab in three of 23 (13%) patients with steroid-refractory UC and in 1/19 (5%) treated with placebo at 2 weeks and the rates were 39% and 30%, respectively, at 6 weeks. These differences, however, were not significant. The definitive evidence for role of infliximab in UC came in 2005 when Active Ulcerative Colitis Trials (ACT1 and ACT2) were published.[24]In these two trials adult patients with moderate to severe UC not responding to standard treatment were randomized to infliximab or placebo. In both the studies, a significantly higher proportion of patients in the infliximab groups (5 or 10 mg/kg at weeks 0, 2, 6 and then every 8 weeks) than in the placebo groups achieved clinical response and remission at week 8 (61% and 37%), and these outcomes were generally maintained through till the end of the studies. These data did not show any major differences in efficacy between the two doses of infliximab (5 and 10 mg/kg). Furthermore, infliximab treatment also correlated with significant differences in the proportion of patients who experienced mucosal healing,[25] an important finding in the light of recent evidence suggesting that mucosal healing is significantly associated with a low risk of future relapse and need for colectomy.[26] In both the studies, infliximab-treated patients successfully discontinued corticosteroid use in a significantly higher percentage compared with the placebo-treated group. Finally, infliximab also seems to be effective in reducing colectomy rates in severe UC not responding to steroids during short and long-term follow-up.[27,28]

In a recent meta-analysis, infliximab was effective when compared to placebo in inducing remission in patients with moderate to severe active UC (relative risk 0.72; 95 % confidence interval 0.57 – 0.91).[29] In another systemic review published in 2007, authors found that short-term response of infliximab in acute severe UC was 65% in contrast to 33% for placebo with an estimated odds ratio for response being 3.6 (95% confidence interval 2.67–4.95) and number needed to treat being 3; corresponding figures for response during long-term follow-up were 53% and 24%, respectively.[30] Adalumimab is an entirely human monoclonal antibody that binds to TNF. It was initially assumed to be more effective with lesser side effects than infliximab. Ulcerative colitis long-term remission and maintenance with adalimumab (ULTRA 1[31] and ULTRA 2[32]) trials were conducted to look for efficacy of this fully humanized molecule in management of UC.Although ULTRA1 trial established the safety and efficacy of adalimumab for inducing clinical remission, higher than expected response rates were seen in placebo patients for several secondary end points, including clinical response and mucosal healing.ULTRA 2 trial was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy of adalimumab in induction and maintenance of clinical remission in patients with moderate to severe UC who received concurrent treatment with oral corticosteroids or immunosuppressants. Overall rates of clinical remission at week 8 were 16.5% on adalimumab and 9.3% on placebo (P =0.019); corresponding values for week 52 were 17.3% and 8.5% (P =0.004). Also in the same trial minimal incremental benefit was shown in patients who were previously exposed to anti TNF therapy.

Most studies of biological agents in UC have been compared to either placebo or other standard treatment. Little data exists comparing biological with steroids for induction of remission in steroid naïve patients’ of active UC. In a pilot study by Ochsenkuhn et al[33], patients with acute UC with a modified Truelove and Witts activity score of more than 10 for at least 2 weeks and not receiving immunomodulators or more than 10 mg/day prednisolone were randomized to receive either three intravenous infusions of infliximab at 5 mg/kg or highdose prednisolone (1.5 mg/ kg body weight) daily for 2 weeks, followed by 1 mg/kg for 1 week, followed by a weekly reduction of 5 mg. Five of six patients in the infliximab group and six of seven patients in the prednisolone group showed therapeutic success after 3 weeks as well as after 13 weeks. Although this pilot study demonstrated the efficacy of infliximab, larger studies are required to determine whether it is better than steroids as the first line treatment for active UC.

In patients with steroid-refractory UC, rescue therapies include infliximab or cyclosporin. However, there is scant data comparing these two effective treatment options. In a parallel, open labeled randomized controlled trial Laharie et al[34] compared intravenous cyclosporin (2 mg/kg per day for 1 week, followed by oral drug until day 98) with infliximab (5 mg/kg on days 0, 14, and 42). Treatment failure occurred in 60% patients given cyclosporin and 54% given infliximab (p=0·52). 16% patients in the cyclosporin group and 25% in the infliximab group had severe adverse events.The results of this trial showed that treatment choice should be guided by experience and cost of treatment.

Safety of Biologics

With biologic agents targeting specific factors involved in immuno surveillance, concerns over side effects and safety have been raised with both short- and long-term trials. Also most of these drugs are usually given in addition to conventional drugs like mesalamine, azathioprine and steroids So, drug interactions and cumulative toxicities may also occur. One of the main concerns of biologicals is the occurrence of opportunistic infections. Tuberculosis and hepatitis B remain an important concern. In fact, tuberculosis should always be ruled out before giving such therapy. Some of the adverse events are specific to certain drugs or combination of drugs. Progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy (PML) has been reported with the use of natalizumab; hepatosplenic lymphoma has been reported with the use of combination therapy with infliximab and azathioprine. Also, patients develop antibodies against these biological agents, which may cause acute or delayed infusion reactions. Physicians using these drugs should be aware of these unique side effects and should know strategies to minimize the development of antibodies. One of the concerns of infliximab therapy in patients with acute severe UC has been possible increase in the perioperative complications if colectomy is required following failure of infliximab therapy. In a meta-analysis on 706 patients from five studies, the authors studied certain possible associations between infliximab treatment before surgery and post-operative infectious complications (odds ratio 2.24) and increased risk of overall post-operative complications (odds ratio 1.80) during short-term follow-up.[35] This needs to be kept in mind while administering infliximab in patients with steroidrefractory acute severe UC. However, a recent study gave some hope to such patients by use of second-line rescue therapy.36In this retrospective study on 86 patients with steroid- refractory acute severe UC failing to respond to first-line rescue therapy with either cyclosporine or infliximab, a second-line rescue therapy with either infliximab or cyclosporin was administered. A second-line rescue therapy with either cyclosporine or infliximab, was found effective.[36] It is important, however, to reiterate that these treatment options should be considered as a bridge to another long-term immunosuppressive therapy, like a thiopurine (e.g. azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine) as without this the first or second-line rescue therapy only delays colectomy and does not prevent it.

In conclusion, anti TNF alpha antibodies are the new and effective drugs used for treating acute severe steroid-refractory UC. This may function as rescue therapy when surgical options are limited. When used as a bridge to thiopurine treatment, steroid-free remission is maintained in a large proportion of patients. More studies are required in this issue.

References

- Wright JP, O’Keefe EA, Cuming L, Jaskiewicz K. Olsalazine in maintenance of clinical remission in patients with ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1837–42.

- Misiewicz JJ, Lennard-Jones JE, Connell A, Baron JH, Avery Jones F. Controlled trial of sulphasalazine in maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 1965;1:185–8.

- Prakash A, Markham A. Oral delayed-release mesalazine: a review of its use in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Drugs. 1999;57:383–408.

- Solberg IC, Lygren I, Jahnsen J, Aadland E, Høie O, Cvancarova M,et al. Clinical course during the first 10 years of ulcerative colitis: results from a population-based inception cohort (IBSEN Study). Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:431–40.

- Henriksen M, Jahnsen J, Lygren I, Sauar J, Kjellevold Ø, Schulz T, et al. Ulcerative colitis and clinical course: results of a 5-year population-based follow-up study (the IBSEN study). Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:543–50.

- Kumar S, Ghoshal UC, Aggarwal R, Saraswat VA, Choudhuri G. Severe ulcerative colitis: prospective study of parameters determining outcome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:1247–52.

- Chakravarty BJ. Predictors and the rate of medical treatment failure in ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:852–5.

- Truelove SC, Willoughby CP, Lee EG, Kettlewell MG. Further experience in the treatment of severe attacks of ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 1978;18:1086–8.

- McGuire BB, Brannigan AE, O’Connell PR. Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Br J Surg. 2007;94:812–23.

- Beliard A, Prudhomme M. Ileal reservoir with ileo-anal anastomosis: long-term complications. J Visc Surg. 2010;147:e137–e44.

- Travis SPK, Stange EF, Lemann M, Oresland T, Bemelman WA, Chowers Y,al. European evidenced-based consensus on management of ulcerative colitis: current management. J Crohns Colitis. 2008;2:24–62.

- Frei P, Biedermann L, Nielsen OH, Rogler G. Use of thiopurines in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:1040–8.

- Sjoberg M, Walch A, Meshkat M, Gustavsson A, Järnerot G, Vogelsang H, et al. Infliximab or cyclosporine as rescue therapy in hospitalized patients with steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis: a retrospective observational study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:212–8.

- Lichtiger S, Present DH, Kornbluth A, Gelernt I, Bauer J, Galler G, et al. Cyclosporine in severe ulcerative colitis refractory to steroid therapy. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1841–5.

- Moskovitz DN, Van Assche G, Maenhout B, Arts J, Ferrante M, Vermeire S, et al. Incidence of colectomy during long-term follow-up after cyclosporine-induced remission of severe ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:760–5.

- Bamba S, Andoh A, Imaeda H, Ban H, Kobori A, Mochizuki Y,et al. Prognostic factors for colectomy in refractory ulcerative colitis treated with calcineurin inhibitors. Exp Ther Med. 2012;4:99–104.

- Molnar T, Farkas K, Szepes Z, Nagy F, Szûcs M, Nyári T, et al. Long-term outcome of cyclosporin rescue therapy in acute, steroid-refractory severe ulcerative colitis. United European Gastroenterol J. 2014;2:108–12.

- Shibolet O, Regushevskaya E, Brezis M, Soares-Weiser K. Cyclosporine A for induction of remission in severe ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005:CD004277.

- Bilsborough J, Viney JL. From model to mechanism: lessons of mice and men in the discovery of protein biologicals for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2006;1:69–83.

- Zhang YZ, Li YY. Inflammatory bowel disease: pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:91–9.

- Bell SJ, Kamm MA. Review article: the clinical role of anti-TNF antibody treatment in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:501–14.

- Sands BE, Tremaine WJ, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts PJ, Hanauer SB, Mayer L,et al. Infliximab in the treatment of severe, steroidrefractory ulcerative colitis: a pilot study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001;7:83–8.

- Probert CS, Hearing SD, Schreiber S, et al. Infliximab in moderately severe glucocorticoid resistant ulcerative colitis: a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2003;52:998–1002.

- Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Reinisch W, Olson A, Johanns J,et al. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2462–76.

- Froslie KF, Jahnsen J, Moum BA, Vatn MH, Group I. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: results from a Norwegian population-based cohort. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:412–22.

- Sandborn WJ. Mucosal healing with infliximab: results from the active ulcerative colitis trials. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2012;8:117–9.

- Jarnerot G, Hertervig E, Friis-Liby I, et al. Infliximab as rescue therapy in severe to moderately severe ulcerative colitis: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1805–11.

- Kohn A, Daperno M, Armuzzi A, Cappello M, Biancone L, Orlando A,et al. Infliximab in severe ulcerative colitis: shortterm results of different infusion regimens and long-term followup. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:747–56.

- Ford AC, Sandborn WJ, Khan KJ, Hanauer SB, Talley NJ, Moayyedi P. Efficacy of biological therapies in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:644–59.

- Gisbert JP, Gonzalez-Lama Y, Mate J. Systematic review: Infliximab therapy in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:19–37.

- Reinisch W, Sandborn WJ, Hommes DW,D’Haens G, Hanauer S, Schreiber S, et al. Adalimumab for induction of clinical remission in moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis: results of a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2011;60:780–7.

- Sandborn WJ, van Assche G, Reinisch W, Colombel JF, D’Haens G, Wolf DC, et al. Adalimumab induces and maintains clinical remission in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:257–65.

- Ochsenkuhn T, Sackmann M, Goke B. Infliximab for acute, not steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis: a randomized pilot study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:1167–71.

- Laharie D, Bourreille A, Branche J, Allez M, Bouhnik Y, Filippi J,et al. Ciclosporin versus infliximab in patients with severe ulcerative colitis refractory to intravenous steroids: a parallel, open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380:1909–15.

- Yang Z, Wu Q, Wang F, Wu K, Fan D. Meta-analysis: effect of preoperative infliximab use on early postoperative complications in patients with ulcerative colitis undergoing abdominal surgery. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:922–8.

- Leblanc S, Allez M, Seksik P, Flourié B, Peeters H, Dupas JL, et al. Successive treatment with cyclosporine and infliximab in steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:771–7.

- Chey WY. Infliximab for patients with refractory ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001;7:S30–3.

- Kaser A, Mairinger T, Vogel W, Tilg H. Infliximab in severe steroidrefractory ulcerative colitis: a pilot study. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2001;113:930–3.

- Mamula P, Markowitz JE, Brown KA, Hurd LB, Piccoli DA, Baldassano RN. Infliximab as a novel therapy for pediatric ulcerative colitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;34:307–11.

- Kohn A, Prantera C, Pera A, Cosintino R, Sostegni R, Daperno M. Anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha (infliximab) in the treatment of severe ulcerative colitis: result of an open study on 13 patients. Dig Liver Dis. 2002;34:626–30.

- Actis GC, Bruno M, Pinna-Pintor M, Rossini FP, Rizzetto M. Infliximab for treatment of steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis. Dig Liver Dis. 2002;34:631–4.

- Su C, Salzberg BA, Lewis JD, Deren JJ, Kornbluth A, Katzka DA, et al. Efficacy of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in patients with ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2577–84.

- Gornet JM, Couve S, Hassani Z, Delchier JC, Marteau P, Cosnes J, et al. Infliximab for refractory ulcerative colitis or indeterminate colitis: an open-label multicentre study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:175–81.

- Shen EH, Das KM. Current therapeutic recommendations: infliximab for ulcerative colitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:741–5.

|

|

|

|

|

|