|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Quarterly Reviews |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

Hepatic lymphoma, Non hodgkin’s lymphoma, infiltrative liver disease |

|

|

Rajesh Kumar Padhan,* Prasenjit Das,** Shalimar*

Department of Gastroenterology

and Human Nutrition*

Department of Pathology*

All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India

Corresponding Author:

Dr Shalimar

Email: drshalimar@yahoo.com

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.239

Abstract

Primary hepatic lymphoma (PHL) is a lymphoproliferative disorder confined to the liver without evidence of involvement of spleen, lymph nodes, bone marrow or other lymphoid structures. This is in contrast to Non Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (NHL) that often involves the liver as a secondary manifestation. PHL is a rare disease and constitutes 0.016 % of all cases of NHL. PHL typically occurs in middle aged men, and usually the chief presenting symptoms are non specific which includes right upper quadrant pain, B symptoms like fever and weight loss and constitutional symptoms. Most frequent physical finding is hepatomegaly which occurs in 75% of patients. Jaundice is rare and present only in less than 5% of patients. Majority of PHL originates from B cells. The blood investigations and imaging findings are nonspecific. Histopathology is essential and confirms the diagnosis. Treatment modalities include combination of surgical resection, chemotherapy and radiotherapy. The prognosis without therapy is grim. The prognosis and management of PHL is different from hepatocellular carcinoma or metastatic disease, hence it is essential to differentiate it from these diseases. The purpose of this review is to emphasize the importance of accurate diagnosis before implementing therapeutic plan for any hepatic space occupying lesion in liver.

|

48uep6bbphidvals|697 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Liver is the largest reticulo-endothelial organ of the body. Hence it is not surprising that it is commonly involved in Non- Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL). In fact it is involved in 40% of NHL patients at presentation.[1] However isolated involvement of the liver with no evidence of involvement of the spleen, lymph nodes, bone marrow or other lymphoid structures is rare and is known as primary hepatic lymphoma (PHL).

Epidemiology

The exact incidence and prevalence of PHL is not known. PHL is rare and comprises 0.4% of all cases of extra nodal NHL and 0.016% of all cases of NHL.[2] With increasing incidence of NHL it is assumed that the incidence of PHL is also increasing.[3] The widely accepted diagnostic criteria for PHL were proposed by Lei et al in 1998,[4] these include: (1) at presentation, the patient’s symptoms are caused mainly by liver involvement (2) absence of palpable lymphadenopathy and no radiologic evidence of distant lymphadenopathy (3) absence of leukemic blood involvement in the peripheral blood smear. Lei identified 90 cases of PHL that had been described in the literature between 1981 and 1993 with the help of these criteria.[4] Diagnosis of PHL requires a liver biopsy compatible with lymphoma and the absence of lympho-proliferative disease outside the liver.[5]

Pathogenesis

The etiopathogenesis of PHL is unknown. Multiple etiological factors have been proposed. Recent reports have described an increased incidence of PHL in patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. HCV infection was noted in 21% of immune competent PHL patients from France. Most of these HCV infected patients had a high-grade B-cell lymphoma.[5] The possible mechanisms proposed for the development of lymphoma in these patients include: (1) B-cell stimulation leading to polyclonal and then monoclonal B-cell expansion, (2) HCV induced (14; 18) translocation leading to over expression of the anti-apoptotic factor, bcl-2, and monoclonal IgH rearrangement.[6] (3) alteration in the transcriptional regulation of genes like p21, p53, and H-ras by the viral core and/ or NS35 proteins.[7,8]

The association of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection with PHL is controversial. Aozasa et al[9] reported 20% prevalence of hepatitis B surface antigen positivity in a series of 69 patients with PHL, 52 of whom were from Western countries and 17 were from Japan. However Lei4 reported a series of only 7 cases from Hong Kong which is an endemic area for Hepatitis B and the disproportionately lower number of cases of PHL possibly argue against a pathogenic role of hepatitis B in the development of this disease. Based on all the available data any apparent association between hepatitis B virus infection and PHL can be considered coincidental only.[10] Other viruses like Epstein Barr virus (EBV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) have been implicated in the pathogenesis of PHL.

EBV is important in a post-transplant setting where reactivation of EBV may trigger the onset of PHL. Normally T cells prevent polygonal B cell proliferation. In immunocompromised patients with deficient regulatory T cell function, EBV causes unchecked polyclonal B-cell proliferation and hence possibly lymphoma originates. Following transplant the EBV genome and its products have been demonstrated in the lymphoma cells.[11] PHL has also been reported in patients with AIDS, cyclosporine-treated transplant recipients and systemic lupus erythematosus patients.

Clinical features

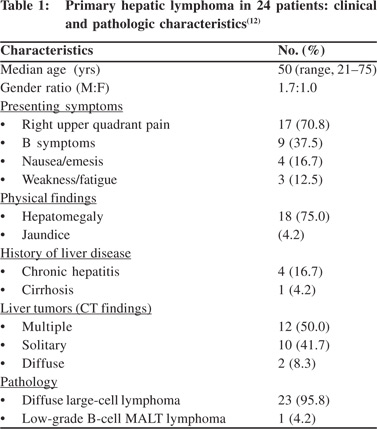

PHL primarily is a disease of middle-aged adults with a male predominance. It commonly presents at 50 years of age (range: 21-75 years) with a male to female ratio of 1.7:1.[12] The clinical presentation is variable. However, the most common presenting symptom is abdominal pain or discomfort, which may occur in up to 70% of patients.[13] B symptoms occur in one third of patients. Around 10% of patients have a history of pre-existing liver disease like chronic hepatitis B or C, cirrhosis, or hemochromatosis.[14] Jaundice is seen in less than 5% of patients.[11] The presence of splenomegaly goes against a diagnosis of PHL. Congestive splenomegaly can occur in PHL due to hepatic dysfunction and portal hypertension.6 Rare presentations of PHL reported in literature include acute liver failure and acute or chronic hepatitis mimics.[15-17] The clinical and pathologic characteristics in a case series by Page RD et al[12] are shown in Table 1.

Laboratory findings

In PHL complete blood counts are usually within normal range compared to secondary hepatic lymphoma as the bone marrow is not involved in PHL. Abnormal blood test results indicate secondary hepatic lymphoma or splenomegaly due to liver dysfunction in PHL. Liver function tests may show nonspecific derangements including altered aspartate aminotransferases, alanine aminotransferases, alkaline phosphatase, and bilirubin levels. Liver dysfunction may be either cholestatic or hepatocellular in pattern. Lactate dehydrogenase elevation, suggesting tissue necrosis, may be seen in 30–80% of patients.[4]

Beta-2-microglobulin elevation is found in about 90% of patients.[12] CRP and ESR is elevated in one third of patients. Tumor markers like alpha-fetoprotein and carcinoembryonic antigen are not elevated[6] thus help to differentiate it from primary liver cancer and metastatic liver involvement. All patients should undergo screening for SLE, HIV, hepatitis B, hepatitis C and EBV viruses. Patients with hepatitis C infection may show associated essential mixed cryoglobulinemia type II.[5] Abnormal coagulation profile, hypercalcemia and monoclonal spike on electrophoresis are rare findings.

Imaging studies

Radiologically, primary hepatic lymphoma can present in three forms[18]

1. A solitary lesion

2. Multiple lesions within the liver

3. Diffuse hepatic infiltration

The imaging appearance of hepatic lymphoma is nonspecific and may resemble a hypovascular metastasis.

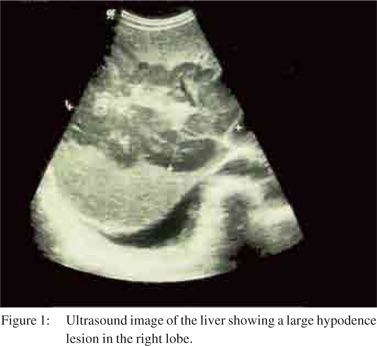

Colon, stomach, lung, prostate and transitional cell carcinomas are the most common primary tumors with hypovascular metastasis pattern to the liver.[19] Infectious (such as fungal and tubercular) and inflammatory (such as sarcoidosis) pathologies can sometimes result in similar imaging appearances with multiple focal hepatic lesions. On ultrasound imaging (Figure 1) majority are hypoechoic as compared to surrounding normal liver parenchyma due to high cellularity and lack of background stroma.[20]

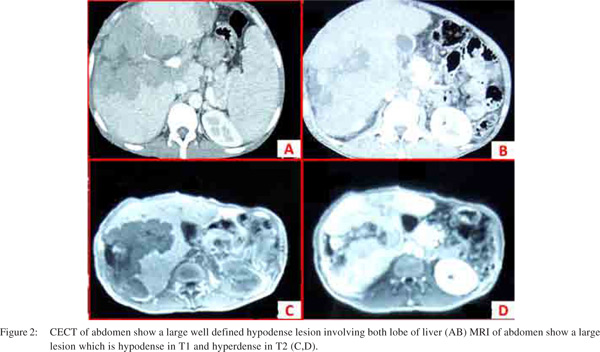

In the series by Emile et al[21] the most common presentation was a solitary lesion (55–60%) followed by multiple lesions (35–40%). Diffuse infiltration was uncommon and had a worse prognosis. In another series of 12 patients, 3 presented with a single focal lesion, 8 with multiple well-defined lesions and only 1 patient presented with diffuse hepatic involvement.[22] On non-contrast CT imaging (Figure 2) PHL lesions appear as hypo-attenuating solid lesions. Following intravenous contrast, 50% of PHL lesions do not enhance, 33% show patchy enhancement, and 16% show ring enhancement.[6] The classical imaging appearance on MRI imaging (Figure 2) is hypointense or isointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2- weighted images.[23] With administration of gadolinium contrast the hypovascularity and ring enhancement maybe better demonstrated.20 On PET scan imaging PHL shows increase in FDG uptake at the site of hepatic lesions.[24] PET scan also helps to rule out secondary lymphoma of the liver.

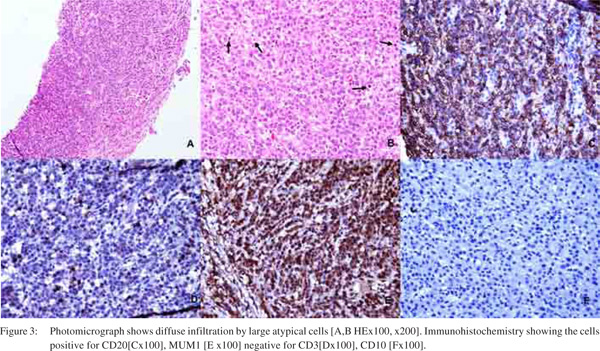

Pathology

Despite all non-invasive methods to detect liver disease histopathological examination is indispensable in most of them for confirmation of diagnosis and treatment (Figure 3). Only a few articles are available regarding histopathology of hepatic lymphomas. Hence clinical, radiological and histological features are elusive. Autopsy study revealed hepatomegaly as the most common presentation (50%) in PHL; however hepatomegaly commonly directs one to look for a primary lympho-reticular malignancy as hepatomegaly is found in 80% cases of hematological malignancies.[25] Other systemic causes of hepatomegaly like steatosis, amyloidosis etc. should always be excluded. Primary hepatic lymphoma may be Hodgkin’s or Non-Hodgkin’s, however the latter is more common. Immunophenotypically B cell is commoner than T cell type, comprising 63% and 25% of hepatic lymphomas, respectively.[26]

Microscopically the lymphomas may show diffuse or nodular pattern of infiltration in scanner view. The diffuse pattern usually also shows sinusoidal pattern involvement. Both patterns can cause destruction of hepatic parenchyma, however the nodular pattern causes more destruction.[25] Amongst the B cell lymphomas, diffuse large B cell type is the commonest followed by chronic lymphocytic lymphoma, Burkitt’s lymphoma and mantle cell lymphomas.[27] Peripheral T cell NHL, NOS is the most common amongst T cell NHLs followed by anaplastic large cell lymphoma and hepatosplenic gamma delta lymphomas, etc.[28] There are a few reported cases of primary mucosal associated lymphoid tissue(MALToma) and unclassifiable small B cell lymphomas involving the liver.[29] Commonly the T cell NHLs involving the liver, show diffuse infiltration patterns. Nodular arrangement is less common.[30]

Differential diagnosis

PHL is a rare disease with non-specific clinical presentation, varying laboratory and radiologic features. Primary hepatic tumors, liver metastases, and systemic lymphoma with secondary hepatic involvement can all present in a fashion similar to PHL. In addition there are case reports of PHL presenting as acute liver failure.[31]

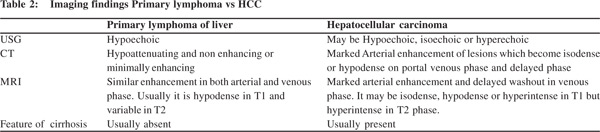

On imaging studies primary hepatic tumors are hypoechoic, isoechoic and hyper-echoic lesions on ultrasound, and on CT scan these show arterial enhancement with wash out on venous phase (Table 2). In comparison, PHL presents as a lesion that is hypoechoic on ultrasound and hypo attenuating, nonenhancing or minimally enhancing on CT scan. Imaging may also demonstrate lesions elsewhere in the body, which may suggests a diagnosis of carcinoma or lymphoma with secondary hepatic involvement. The histological diagnosis of PHL may also be misleading, and initial misdiagnosis of poorly

differentiated carcinoma, embryonal sarcoma, granulomatous cholangitis, inflammatory pseudo-tumor and granulomatous hepatitis have been reported.[26] Immuno-histochemistry, flow cytometry, and karyotyping are essential for accurate diagnosis.[6]

Treatment and prognosis

Since the disease is extremely rare, the basis of treatment protocol is based on case reports or small case series. Treatment options include: i) Surgery ii) Chemotherapy iii) Radiation iv) Combinations of the above modalities.

There are multiple prognostic factors which determine the treatment outcome and prognosis in PHL patients. They are: i) advanced age ii) poor performance status iii) bulky disease iv) unfavorable histology v) elevated lactate dehydrogenase vi) comorbid conditions and vii) immunosuppressed state Surgery is a better option for localized disease with adequate normal liver volume and pre-operative chemotherapy can be tried with an attempt to reduce the tumor volume. In the original case series from Lei, 10 patients were treated with curative surgery. These patients had better performance status, preserved liver function, smaller tumor volume and no significant comorbid conditions. They had a median survival of 22 months.[4] Relapse is usually common after surgery and it can be local or extra hepatic. So there is a distinct role for chemotherapy either as an adjunct to surgery or as single treatment modality as PHL is chemo sensitive. Avlonitis et al[26] reported a series of 14 patients, who were treated surgically followed by adjuvant chemotherapy with a median survival of 20.7 months.

Page et al. performed a retrospective cohort review of 24 patients.[12] These patients were classified based on the presence of at least one of the following pre-treatment risk factors:

1. Serum lactate dehydrogenase level >10% above normal

2. Serum beta-2-microglobulin level >3 mg/L (normal: 0.6–2 mg/L)

3. Tumor mass measuringe >7 cm in greatest dimension

4. Constitutional symptoms

5. Ann Arbor Stage III or Stage IV disease

If patients had none of the above pre-treatment risk factors, they were considered to have a low risk of disease recurrence and were treated with CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) chemotherapy. Patients who had at least one pre-treatment risk factor were considered as high risk for relapse and were treated with alternating triple combination chemotherapy (doxorubicin, methyl prednisolone, cytosine arabinoside and cisplatin, alternating with methotrexate, bleomycin, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and methyl prednisolone, alternating with mesna, ifosfamide, mitoxantrone and etoposide). With this regimen an overall complete remission rate of 83.3% (100% of patients treated with alternating triple therapy) and a 5-year relapse-free survival rate of 83.1% were achieved. Of the 13 patients treated with CHOP-based regimens, 9 achieved complete remission, one partial remission, and another 3 patients had primary refractoriness to therapy. All 8 patients treated with alternating triple therapy achieved a complete remission. The 5-year overall survival rate was 83.1%. However, all patients with primary refractory disease had progressive disease and did not respond to salvage chemotherapy. HCV co-infection did not have any effect on response to chemotherapy.

Other authors did not show similar results. In the case series of 40 patients treated with chemotherapy alone by Avlonitis and Linos[26] the median survival was 14 months.[4] Patients were treated with either combination or single-agent chemotherapy. The median survival was only 6 months. But chemotherapy was used in high risk patients and those who were not fit for surgery with diffuse hepatic involvement, extra hepatic disease or high grade histological subtypes. Moreover, the chemotherapy regimens employed were suboptimal, often consisting of a single agent or steroids alone.

Conclusion

PHL is a rare disease with non-specific clinical presentation, variable laboratory investigation findings and imaging. Moreover there is no specific marker for accurate diagnosis. Tissue histology is mandatory for diagnosis, in deciding the extent of involvement, subtyping of the lymphoma and thus helps in management decision and to workout a possible outcome. It should be considered in any patient of any age who presents with liver mass or infiltration. Early and definite diagnosis is the key as multimodality therapy, can be instituted timely, because due to better sensitivity of these tumors, a better outcome is possible, than the hepatocellular carcinoma or liver secondaries.

References

- Chabner BA, Johnson RE, Young RC, Canellos GP, Hubbard SP, Johnson SK, et al. Sequential nonsurgical and surgical staging of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Ann Intern Med. 1976;85:149–54.

- Freeman C, Berg JW, Cutler SJ. Occurrence and prognosis of extranodal lymphomas. Cancer. 1972;29:252–60.

- Cartwright R, Brincker H, Carli PM, Clayden D, Coebergh JW, Jack A, et al. The rise in incidence of lymphomas in Europe 1985–1992. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35:627–33.

- Lei KI. Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the liver. Leuk Lymphoma. 1998;29:293–9.

- Bronowicki JP, Bineau C, Feugier P, Hermine O, Brousse N, Oberti F, et al. Primary lymphoma of the liver: clinicalpathological features and relationship with HCV infection in French patients. Hepatology. 2003;37:781–7.

- Noronha V, Shafi NQ, Obando JA, Kummar S. Primary non- Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the liver. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2005;53:199–207.

- Ohsawa M, Tomita Y, Hashimoto M, Kanno H, Aozasa K. Hepatitis C viral genome in a subset of primary hepatic lymphomas. Mod Pathol. 1998;11:471–8.

- Chim CS, Choy C, Ooi GC, Liang R. Primary hepatic lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma.2001;40:667–70.

- Aozasa K, Mishima K, Ohsawa M. Primary malignant lymphoma of the liver. Leuk Lymphoma. 1993;10:353–7.

- Mills AE. Undifferentiated primary hepatic non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in childhood. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988;12:721–6.

- Avlonitis VS, Linos D. Primary hepatic lymphoma: a review. Eur J Surg. 1999;165:725–9.

- Page RD, Romaguera JE, Osborne B, Medeiros LJ, Rodriguez J, North L, et al. Primary hepatic lymphoma: favorable outcome after combination chemotherapy. Cancer. 2001;92:2023–9.

- Talamo TS, Dekker A, Gurecki J, Singh G. Primary hepatic malignant lymphoma:its occurrence in a patient with chronic active hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma associated with hepatitis B viral infection. Cancer. 1980;46:336–9.

- Santos ES, Raez LE, Salvatierra J, Morgensztern D, Shanmugan N, Neff GW. Primary hepatic non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas: case report and review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2789–93.

- Mattar WE, Alex BK, Sherker AH. Primary hepatic burkitt lymphoma presenting with acute liver failure. J Gastrointest Cancer.2010;41:261–3.

- Castroagudin JF. Presentation of T cell rich B cell lymphoma mimicking acute hepatitis. Hepatogastroenterology.1999;46:1710–3.

- Kyung Mikang. A case of primary hepatic lymphoma mimicking Hepatitis. Korean J Hepatol. 2005;11:284–8.

- Levy AD. Malignant liver tumors. Clin Liver Dis. 2002;6:147–64.

- Elsayes KM, Narra VR, Yin Y, Mukundan G, Lammle M, Brown JJ. Focal hepatic lesions: diagnostic value of enhancement pattern approach with contrast-enhanced 3D gradient-echo MR imaging. Radiographics. 2005;25:1299–320.

- Maher MM, McDermott SR, Fenlon HM, Conroy D, O’Keane JC, Carney DN, et al. Imaging of primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the liver. ClinRadiol. 2001;56:295–301.

- Emile JF, Azoulay D, Gornet JM, Lopes G, Delvart V, Samuel D, et al. Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas of the liver with nodular and diffuse infiltration patterns have different prognoses. Ann Oncol. 2001;12:1005–10.

- Elsayes KM, Menias CO, Willatt JM, Pandya A, Wiggins M, Platt J. Primary hepatic lymphoma: imaging findings. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2009;53:373–9.

- Rizzi EB, Schinina V, Cristofaro M, David V, Bibbolino C. Non- Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the liver in patients with AIDS: sonographic, CT, and MRI findings. J Clin Ultrasound. 2001;29:125–9.

- Bangerter M, Moog F, Griesshammer M, Merkle E, Hafner M, Ellenrieder V, et al. Usefulness of FDG-PET in diagnosing primary lymphoma of the liver. Int J Hematol. 1997;66:517–20.

- Walz-Mattmüller R, Horny HP, Ruck P, Kaiserling E. Incidence and pattern of liver involvement in haematological malignancies. Pathol Res Pract. 1998;194:781–9.

- Avlonitis VS, Linos D. Primary hepatic lymphoma: a review. Eur J Surg. 1999;165:725–9.

- Bauduer F, Marty F, Gemain MC, Dulubac E, Bordahandy R. Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the liver in a patient with hepatitis B, C, HIV infections. Am J Hematol. 1997;54:265.

- Stancu M, Jones D, Vega F, Medeiros LJ. Peripheral T-cell lymphoma arising in the liver. Am J Clin Pathol. 2002;118:574–81.

- Miyashita K, Tomita N, Oshiro H, Matsumoto C, Nakajima Y, Ito S, et al. Primary hepatic peripheral T-cell lymphoma treated with corticosteroid. Intern Med. 2011;50:617–20.

- Orrego M, Guo L, Reeder C, De Petris G, Balan V, Douglas DD, et al. HepaticB-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of MALT type in the liver explant of a patient with chronic hepatitis C infection. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:796–9.

- CameronAM, Truty J, Truell J, Lassman C, Zimmerman MA, Kelly BS Jr, et al. Fulminant Hepatic Failure from Primary Hepatic Lymphoma: Successful Treatment with Orthotopic Liver Transplantation and Chemotherapy. Transplantation. 2005;80:993–96.

|

|

|

|

|

|