|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Original Articles |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

autoimmune hepatitis, cirrhosis, liver transplantation, acute on chronic lover failure (ACLF) |

|

|

Amarapurkar D, Dharod M, Amarapurkar A.

Departments of Gastroenterology &

Hepatology, Bombay Hospital &

Medical Research Mumbai, India &

SRL and Dr Avinash Phadke

Laboratory, Mumbai

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Deepak Amarapurkar

Email: amarapurkar@gmail.com

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.243

Abstract

Background and Aims: Autoimmune hepatitis is considered to be rare in Asia-Pacific region. There a few long term studies available. This study was planned to estimate the burden, natural history of AIH and challenges associated with management in a single non-transplant tertiary referral center.

Methods: Prospectively maintained data of patients treated as AIH was screened and patients who qualified AIH by retrospective application of simplified criteria's were enrolled. 181 patients qualified. 125 patients with substantial follow up (65 Definite AIH; 81 females; median age 46, range 8 - 79) were included in study.

Results: Prevalence of AIH was 1.3% and 8.74% amongst all liver disease patients and chronic liver disease respectively. 89 patients qualified as Type I AIH, 14 as type II AIH and 22 were autoimmune markers negative. Modes of presentation was acute liver failure (n=8), chronic hepatitis (n=17), cirrhosis (n=89), 50 patients were decompensated), ACLF (n=7), while 2 were clinically asymptomatic. 19 patients had preceding history of drug intake. 33 patients didn't undergo pretreatment liver biopsy. Prednisolone alone was the predominant immunosuppressive agent used, especially in decompensated cirrhotics and those with acute liver failure. First remission rates after first immunosuppression course were 60%, 85% and 63% in type I, type II and autoantibody negative groups. After a median follow up of 7 years (range 1 - 17 years), 15 patients died (12 of liver related complications) and 2 underwent liver transplantation. Failure to normalize ALT had a high hazard ratio predicting liver related death or transplantation. 11 patients had improvement on repeat liver biopsy, with 5 showing complete cirrhosis reversal. 40 patients are on long term maintenance immunosuppression.

Conclusion: AIH, though uncommon, needs to be kept in mind as early treatment is associated with significantly good long term prognosis.

|

48uep6bbphidvals|701 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a disease of unknown etiology characterized by unresolving inflammation of the liver and the presence of interface hepatitis, hypergammaglobulinemia and auto-antibodies.

Diagnosis is based on exclusion of commoncauses of chronic liver disease and by various scoring systems,supported by liver biopsy.[1,2] There is limited epidemiological data on AIH. The prevalence lies between 15 to 200 cases per 1 million people in Western Europe and North America.[3] However due to major burden of chronic viral hepatitis, AIH is considered rare in Asia.[4] In India few studies on AIH have been reported and prevalence is around 5% of all patients with chronic liver disease.[5-11] Clinical manifestations of AIH vary from acute severe presentation, mild inflammatory, autoantibody negative disease and atypical histology and overlap syndromes. AIH has been the first chronic liver disease shown to respond to corticosteroids, in trials first published in 1970.[12] Subsequently, azathioprine and various other immunosuppressants have been shown to have significant effect in altering the natural history of the disease.[13-15] Liver transplantation is effective in decompensated AIH associated cirrhosis, with excellent five year survival rates varying from 83-92%, and is commonly the offered treatment modality in western countries in this section of patients.[16] The key problems are timely diagnosis, use of immunosuppressive agents with minimal side effects, adherence to therapy (which is practically life-long) and management of non-responders to steroids.[17] In India, early diagnosis, apt treatment with immunosuppressants and management of cirrhosis forms the essence of treatment. Liver transplantation as a treatment modality is still low amongst patients with chronic liver disease (CLD) in India. Though there is increasing awareness of AIH in India, data pertaining to long-term outcome is not available. In this study we report the results of prospectively maintained data over a period of 15 years at a tertiary referral center with special reference to long-term follow up, difficult situations encountered in real life like acute presentation, decompensated disease, autoantibody negative patients and patients treated without liver biopsy.

Materials and method

This was a retrospective analysis of a prospectively maintained data-base from 1994 till December 2012 in a tertiary referral center. During this period, a total of 14,873 patients with various liver diseases were seen at our center. We assessed the records of patients who had been diagnosed and treated as autoimmune hepatitis during this period, according to various existing diagnostic criteria’s and treatment indications. We applied the recently published simplified criteria[2] for AIH diagnosis to these patients. 181 patients fulfilled these criteriaand were enrolled in the study. We determined theprevalence of AIH according to this cohort. 56 patients of these 181, who never followed up with us for a substantial period of time to determine treatment response were excluded from subsequent analyses.

In the remaining 125 patients, we studied various demographic parameters, modes of presentation, treatment imparted, response and survival. The patients were classified as ‘probable AIH’ and ‘Definite AIH’ depending on the score obtained by simplified criteria [2] (score 6 = Probable AIH, score e”7 = Definite AIH). Patients previously undiagnosed as AIH were not assessed. There was an overlap of some patients, which we reported [5]. Prospectively maintained data of these 125 patients was assessed for detailed clinical history, family history, history of other autoimmune diseases, relevant clinical examination and biochemical examination which included complete blood count, platelet count, liver function test, serum creatinine and blood sugar assessment.Various autoimmune markers tested in these patients like anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA) performed by indirect immunofluorescence, anti-smooth muscle antibodies (ASMA) performed by indirect immunofluorescence by using gastric smooth muscle fibres and anti-liver kidney microsomal types I (anti LKM1) antibodies performed by solid phase ELISA using recombinant CYP2D6 were recorded. Positive serology was considered when titers were more than 1:40. Serum protein electrophoreses, serum immunoglobulin G level, hepatitis B surface antigen, anti HCV antibodies and HIV performed in these patients were noted as also investigations done to rule out Wilson’s disease, hemochromatosis and cholestatic diseases. History pertaining to alcohol intake was assessed to rule out alcohol associated liver injury. 92 patients had undergone liver biopsy at the time of diagnosis, details of which were noted. Liver biopsy is not essential for the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis, if other laboratory parameters are highly suggestive of the same. Application of simplified criteria for the diagnosis of AIH to patients without a liver biopsy at diagnosis is still not validated[2]. However, since absence of liver biopsy doesnot carry a negative score, the remaining 34 patients who did not undergo liver biopsy butfulfilled the score of 6 on the remaining parameters suggesting probable AIH by the criteria and other etiologies excluded were included in the study. Patients were also classified according to modes of presentation as acute liver failure, chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis (compensated or decompensated), and acute on chronic liver failure (APASL criteria [18]) according to standard definitions. Presence of ascites, encephalopathy and endoscopy findings if any was noted. Previous treatment details were analyzed. Time to normalization of ALT from treatment initiation was recorded. For this study, clinical remission was defined as remission of symptoms with biochemical normalization plus normalization of immunoglobulins levels. Patients presenting with acute liver failure had been diagnosed as AIH based on the exclusion of other causes, presence of autoimmune markers, corroborative histology and fulfillment of simplified criteria’s. There wereautoantibody negative patients who had been considered as AIH on the basis of the exclusion of other causes of liver disease, corroborative histology, and significant immunoglobulin levels and treated accordingly.These patients were considered for the study if they qualified as probable AIH based on other parameters and after exclusion of NASH as a cause due to absence of obesity, insulin resistance or overt diabetes in these patients.

Statistical methods:Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 17 for windows. Categorical data were summarized as frequencies and percentages, while continuous data as median and ranges. Survival was calculated by Kaplan Meir analysis. Cox regression analysis was used to assess the association of various variables with liver related death or transplantation.

Results

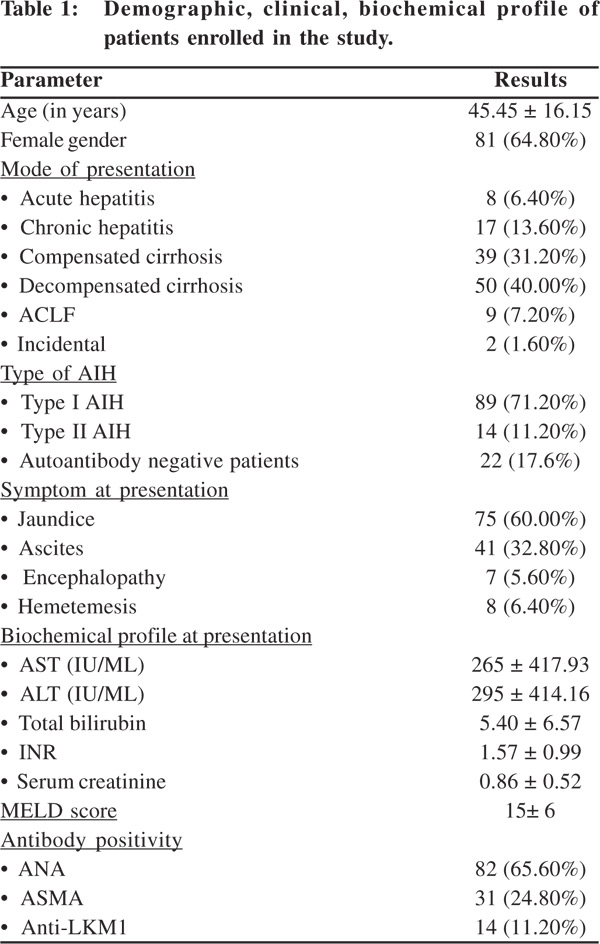

Amongst 14,873 patients who attended our liver clinic in the study period, 181 qualified as AIH by the simplified criteria, giving us a prevalence rate of 1.3%. Prevalence rate amongst patients with chronic liver diseases (including cirrhosis) was 8.74% (165 patients amongst 1886 patients with chronic liver disease).56 patients who werelost to follow up were excluded from further analysis. Of the rest125 patients who were enrolled for further analyses, 65 qualified as definite AIH (with scores e”7) while 60 qualified as probable AIH (score=6). 3 patients had overlap syndrome, 2 hadprimary sclerosingcholangitis with AIH while 1 havingprimary biliary cirrhosis with AIH as evident on histology. Demographic, clinical, biochemical profile of patients enrolled in the study is presented in Table 1.

Majority of patients had cirrhosis at presentation. Type I AIH was the most common AIH type, however a significant proportion of patients were negative for standard antibodies (ANA, ASMA, anti-LKM1). All these patients had evidence of AIH on liver histology and were considered AIH on basis of ‘probable AIH’, having fulfilled simplified AIH criteria.Positive preceding drug history was present in 19 patients, most of who had received indigenous ayurvedic preparations or antituberculosis drugs. Associated autoimmune illnesses were seen in 28 patients, anti-TPO associated hypothyroidism being the commonest (present in 14 patients). Inflammatory bowel disease, insulin dependent diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, psoriasis and toxic goiter were other autoimmune illnesses observed in these patients.Jaundice was the most common presenting complaint followed by ascites. 101 patients underwent endoscopy at diagnosis, of which 56 patients (55.45%) had esophageal varices. Treatment details and treatment response 105 of 125 patients received immunosuppressantsat diagnosis. 16 patients with decompensated cirrhosis, 2 patients who were clinically asymptomatic and 2 patients with acute liver failure who were too sick at diagnosis were not given any immunosuppressants.

Steroidas sole immunosuppressantwasused in 66 patients (62.5%), and thus formed the most common prescription at diagnosis and treatment initiation. 7 of these patients without any evidence of cirrhosis as well lacking other autoimmune diseases received budesonide as the initial immunosuppressant, while the rest received prednisolone in a dose of 1 mg/kg. 37 patients (35.24%) received azathioprine (50 mg or 1mg/kg) along with prednisolone 30 mg as the initial immunosuppressant at diagnosis. 3 patients developed significant cytopenias, necessitating azathioprine withdrawal.

Only 2 patients received mycophenolate as an initial immunosuppressant.74 of 105 patients who received immunosuppression at diagnosis (70.5%) achieved biochemical normalization of ALT and immunoglobulin levels along with resolution of symptoms, thereby achieving a clinical and biochemical remission at a mean duration of 7 ± 3 months of first immunosuppressive regimen. Of these 74 patients, 33 patients (44.6%) achieved remission within 3 months, whereas 34 patients achieved remission from 3 - 12 months. 7 patients achieved remission beyond 12 months.

These 74 patients who attained clinical and biochemical remission were encouraged for repeat liver biopsy, however only 14 patients consented for it. Of these 14 patients who underwent repeat liver biopsy, 11 patients showed complete resolution of histological activity and 5 these showed significant reversal of fibrosis/cirrhosis which was present on initial histology. Though all of our patients with cirrhosis were counseled for liver transplantation, only 2 patients did receive liver transplantation. Immunosuppression was withdrawn initially in 25 patients (11 patients with at least 6 months of clinical, biochemical and histological remission and 14 patients with clinical/biochemical remission of similar duration after adequate patient counseling). Of the 25 patients in whom initial immunosuppression was withdrawn, 10 patients (40%) had a relapse within one year. 9 of these 10 patients received repeat immunosuppression with Prednisolone and azathioprine, while 1 patient received cyclosporine as a rescue immunosuppressant. Second remission was achieved in 9 patients of these 10. Another 6 patients relapsed more than 2 years after immunosuppression withdrawal, with 2 relapsing in the 4th year and 1 in the sixth. All these patients were retreated with immunosuppression; repeat remission achieved in 4 of them.

The remaining 9 patients in whom immunosuppression was withdrawn are in longterm remission with periodic surveillance for disease activity.28 patients (26.67%) were primary nonresponders. 23 of these patients had underlying cirrhosis. Second immunosuppressant was added in 8 patients (azathioprine in 5 and mycophenolate in 3) after a mean duration 12 months of primary immunosuppression, of which 2 patients attained remission subsequently. Presently, 40 patients are on long term maintenance immunosuppression, while in the rest immunosuppression has been discontinued either because of sustained remission (n = 9), treatment adverse events (n = 2), treatment non-response (n = 31) or subsequent contraindications for immunosuppression (n = 23). 2 patients had developed severe cytopenias on azathioprine, which had to be stopped. The cytopenias recovered with standard care. 23 patients who developed subsequent contraindications for immunosuppression were mostly cirrhotic, who either further decompensated or developed significant infective complications.

Factors determining remission

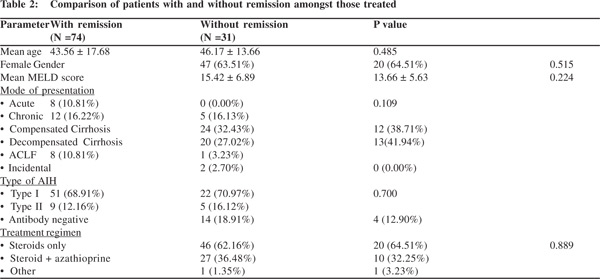

We compared various factors like age at presentation, gender, mode of presentation, MELD score at baseline, type of AIH and treatment regimen given at baseline, to determine whether any factor predicted remission (Table 2). However, none was found to be of significance across the two groups (with and without remission) on univariate analysis. There was no difference of remission in those treated with only steroids and those treated with steroid and azathioprine combination.

Comparison of various types of AIH

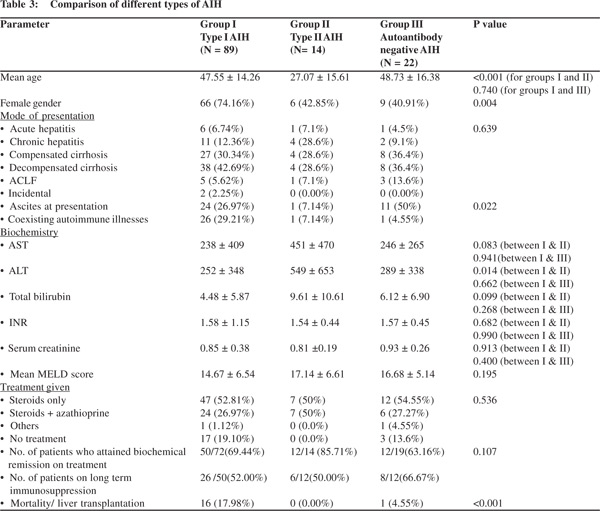

We compared patients of type I AIH with type II AIH and autoantibody negative patients (Table 3). Patients with type II AIH were significantly younger as compared to the other two groups. Almost 75%of type I AIH patients were females, as against only 40% of patients of other two groups. There was no statistical difference in the type of liver disease at presentation across the three groups, majority of patients presenting with cirrhosis. However, numerically, higher percentage of Type II AIH patients had chronic hepatitis at presentation. Similarly, ascites was present in half of patients who were antibody negative, but was present in only 7% of type II patients. Patients with Type II AIH had higher mean AST, ALT and bilirubin levels as compared to other two groups. Patients across three groups had comparable MELD scores at presentation. Coexisting autoimmune illnesses were rare in patients with type II AIH and antibody negative group (1 type II patient had IDDM, whereas 1 antibody negative patient had UC). There was no difference in the treatment given to patients across three groups, with steroids as a single agent being the most common form of immunosuppression. Highest remission rates were seen in type II AIH patients (85%), followed by type I AIH patients (69%), with antibody negative group having the worst remission rate of 63%, however the differences were not statistically significant. 14 patients of type I AIH have died and 2 underwent liver transplantation. All of our type II AIH patients are alive.

Comparison of patients according to types of liver injuries at presentation

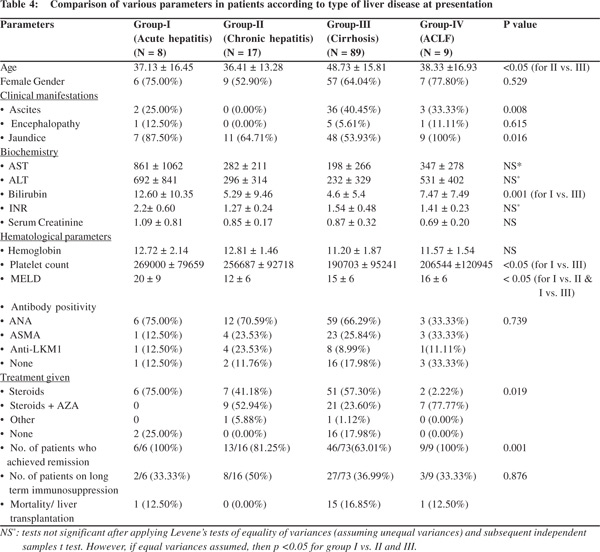

We compared patients according to the type of liver injury at presentation i.e. as acute hepatitis (Group I), chronic hepatitis (group II), cirrhosis (group III) and ACLF (group IV). Since incidentally detected patients were only 2, we excluded them from this comparative analysis. Patients with cirrhosis were significantly older as compared to patients in other 3 groups. Females formed the majority across four groups though the proportion varied (differences being statistically non-significant across groups). As expected, higher proportion of patients with cirrhosis had ascites at presentation, whereas jaundice was significantly higher in those with acute hepatitis or ACLF at presentation. Biochemical and hematological profiles are as in the Table 4. Patients with acute hepatitis had significantly higher transaminases and bilirubin levels as against other 3 groups, whereas patients with cirrhosis had significant thrombocytopenia. Patients with acute hepatitis had a higher MELD score at presentation, due to elevated bilirubin and INR levels. There was no statistical difference in antibody positivity rates across the four groups. Higher percentage of chronic hepatitis and ACLF patients received steroid and azathioprine combination treatment at initiation, while steroids as the sole immunosuppressant formed higher treatment strategy in patients with cirrhosis. This was because cytopenias associated with decompensated cirrhosis precluded us from starting azathioprine in many patients. All our patients in acute hepatitis and ACLF groups treated with immunosuppression achieved biochemical remission initially, whereas remission rates were a poor 63% in cirrhotic population. Almost a third of patients across the four groups are on long term immunosuppression. In the rest, immunosuppressants have been stopped wither due to sustained clinical and biochemical remission, or due to adverse effects or treatment failure.

In the acute hepatitis group, 4 patients had a history of receiving ayurvedic/antitubercular medicines in the immediate past.All patients were negative for viral markers and Wilson’s disease was ruled out with serum ceruloplasmin estimations. Liver biopsy was done in 5 patients, 3 of whom showed classical interface hepatitis, 1 had sub-massive necrosis and 1 had associated bile duct injury along with interface hepatitis. None of the patients had significant copper deposition in the liver tissue as estimated by dry copper weight. Immunosuppression was withdrawn in 3 patients, 1 of whom had a severe relapse, which was not responsive to standard immunosuppression and required cyclosporine as rescue therapy. 2 patients had disease flares while on maintenance immunosuppression, requiring escalation of immunosuppression.

Special populations

1. Patients treated without obtaining a liver biopsy at diagnosis

Liver biopsy was not done at point of diagnosis in 33 patients (27.2%) of 125 patients enrolled in study (8 males, median age 53 years). These patients qualified as ‘Probable AIH’ on simplified criteria’s on rest 3 parameters, and were thus included in study. Viral hepatitis B and C, occult HBV, Wilson’s disease and hemochromatosis had been ruled it on all 33 patients with adequate investigations. There was no history of significant alcohol intake in any of these patients. 11 of these patients (33.33%) had evidence of second autoimmune disease apart from liver involvement. 29 patients (87.88%) had underlying cirrhosis (21 were already decompensated at presentation), 3 presented as acute liver failure while 1 patient qualified as ACLF (by APASL definition). Presence of significant ascites (21 patients) and deranged coagulation parameters (INR >2.5, 7 patients) were main factors, which prevented us from subjecting these patients to liver biopsy, and none of the patients consented for transjugular liver biopsy. After ruling out significant sepsis and adequate patient counseling, immunosuppression was initiated in 22 patients. Prednisolone in isolation, in a dose of 1 mg/kg, was the predominant form of immunosuppression being given to 19 patients. Only 3 patients, without significant cytopenias and stable compensated liver disease received azathioprine and Prednisolone combination as initial immunosuppression. 15 patients of these achievedbiochemical remission at a mean period of 6 ± 8 months of immunosuppression. Immunosuppression was withdrawn in all of these patients after 6 months of sustained biochemical remission.2 patients from the rest 7 on immunosuppression died at a mean duration of 2 years from diagnosis. 4 patients are on long term maintenance immunosuppression, while 1 patient stopped medication on his own. Median follow up of patients in this group is 2 years (range 1 – 7 years).

2. Decompensated cirrhosis/End stage liver disease at presentation

50 patients (40%) presented with decompensation at diagnosis.

32 patients (64%) were females whereas median age of presentation was 46 years. Only 23 patients had undergone liver biopsy at diagnosis, with remaining 27 fulfilling the criteria for probable AIH by simplified criteria’s. These patients had significant cytopenias at presentation, with meanhemoglobin of 8 ± 2gm%, platelet count of 65,000 ± 13,000 /cu mm. In view of these cytopenias, azathioprine was not considered for immunosuppression in them.35 patients without any past history or recent evidence of infection were started on Prednisolone. 24 of these 35 patients (68.57%) achieved normalization of transaminases after a mean 7 ± 3 months of immunosuppression. Immunosuppression was withdrawn in 12 patients, 7 of whom relapsed and had to be restarted on steroids. Thus there was a significant relapse rate after steroid withdrawal. 15 patients were receiving long term maintenance steroid in addition to standard cirrhosis care. After a median follow up of 3years, 5 patients had died whereas 2 patients had received liver transplantation.

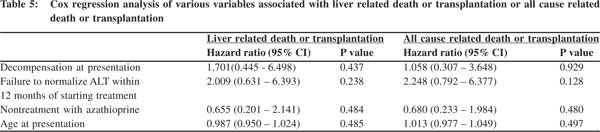

Factors associated with death or transplantation After a median follow up of 7 years (range 1 - 17 years), 15 patients have died. In 3 of them, deaths have been due to nonliver related causes. 10 patients have died due to complications of cirrhosis (5 were already decompensated at presentation), whereas 1 death has occurred each in patients with acute failure and acute-on-chronic liver failure. Only 2 patients received liver transplantation. Of the 12 patients who died due to liver related causes, 11 deaths occurred within first 5 years of diagnosis, at a median of 2 years from diagnosis. 25 patients are already into second decade of follow up. Age at diagnosis, presence of decompensated liver disease, azathioprine as a part of immunosuppression regimen and treatment response in terms of transaminase normalization at 12 months were evaluated by a regression model to predict liver related death or transplantation as well all-cause related death or transplantation. Failure to normalize transaminase at 12 months was associated with a hazard ratio of 2 in predicting liver/all cause related death or transplantation.

However the difference was statistically not significant (p > 0.05). (Table 5)

Discussion

Autoimmune hepatitis, though considered uncommon,needs to be considered in the differential diagnosis of any type of liver disease presentation, whether acute, chronic or cirrhotic. Female gender, insignificant alcohol intake, and negative viral markers should raise the suspicion of autoimmune liver disease especially in those patients without any risk factor for NAFLD. International autoimmune hepatitis group (IAIHG)[2,19], American association of study of liver diseases (AASLD)[20], and British society of gastroenterology (BSG)[21] have established individual set of guidelines for diagnosis and management of autoimmune liver diseases. The criteria developed by IAIHG have evolved over the years from the original to revised simplified criteria. These criteria and guidelines have been developed based on studies in the western population. Moreover, 50% to 70% of the guidelines by AASLD and BSG are based on suspect evidence, conflicting experiences and divergent opinions[22]. In such a scenario, the diagnostic decisions, interpretation of various tests and therapeutic decisions are still guided by clinical judgement, tailored to an individual clinical situation [17,22]. Through this study, we present our experience in diagnosing and managing patients with autoimmune liver disease.

The prevalence of AIH was 8.7% amongst patients with chronic liver disease in our study. This compares with the western data suggesting prevalence rates of 11-23%[23]. In previous studies from India, AIH contributed to 1.9 – 4.6 % cases amongst CLD5-11. In our previous study [5], AIH contributed to 4.5 % cases of CLD, while in study by Gupta et al[6], AIH contributed to 3.4% of cases of CLD.65% of patients in our series were females, and AIH was predominantly seen in middle aged population. 89 (71%) patients had cirrhosis on presentation, of which 50 were already decompensated. This may be due to a referral bias, as there is more probability of a patient with cirrhosis being referred to a tertiary center. However, previous studies from India too have mentioned high incidence of decompensated cirrhosis at presentation[5-11]. 89 of our patients classified as Type I AIH, which compares favorably to other studies mentioning similar rates of Type I AIH [5-11]. 14 patients had significant titers of Anti-LKM1 antibodies, thus qualifying as Type II AIH. This group was male predominant and quite young as compared to those with ANA/ASMA positivity.

22 patients were negative for conventional autoimmune markers, viral markers and had no risk factor for NAFLD. This group probably represented cryptogenic hepatitis.Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease has been implicated in 21-63% of patients, and autoimmune hepatitis is a likely diagnosis in 10-54% of individuals with cryptogenic hepatitis[25,26]. Autoantibody negative autoimmune hepatitis may be associated with non-conventional antibodies like soluble liver antigen, may have a yet undiscovered pathognomonic antibody or the antibody expression may be suppressed or delayed[24]. 63% of our patients from this group achieved remission with immunosuppression, which compares with other studies demonstrating 67-87% response rates.A confident diagnosis can be madeusingthe international AIH scoring system and immunosuppressants initiated. A 3 month trial of corticosteroids is warranted in these patients after considering laboratory and biochemical parameters [17, 24, 27].

In our study, 33 patients were diagnosed and treated without liver biopsy. Clinical, biochemical profile, response to treatment and outcome were similar to those patients who had histology proven AIH. Bjornson et al have shown in a recent study that most patients with laboratory features of AIH have a compatible liver histology[28]. The authors showed that, even without the biopsy, patients could qualify as probable AIH by simplified criteria’s. In the same study, presence of atypical liver histology findings had little impact on patient management[28]. The findings from our study and study by Bjornson et al argue that pretreatment liver biopsy may not be necessary if the patients satisfy laboratory parameters of AIH diagnosis.

Fifty patients in our study first presented with decompensation.>50% of these patients could not be subjected to percutaneous liver biopsy in view of ascites and/or significant coagulopathy. Due to cost restraints and lack of consent, these patients were not subjected to transjugular liver biopsy as they qualified for probable AIH based on other parameters. In view of significant cytopenias, only prednisolone was used for immunosuppression in patients without any contraindication for the same. Thus, cytopenias commonly associated with cirrhosis, especially end stage disease, preclude azathioprine as an agent of immunosuppression[22].

Demonstration of remission is difficult in these patients, transaminases may not normalize, immunoglobulins may be persistently high, and patients are symptomatic due to underlying liver failure. In such a circumstance, decision to withdraw immunosuppression depends on clinical judgement

in the absence of clear guidelines. Indeed withdrawal of immunosuppression is associated with significant relapse rate as was evident in our study, where 7 patients amongst 12 in whom immunosuppression was withdrawn, relapsed.

Autoimmune hepatitis can have a severe fulminant presentation or a patient with indolent chronic disease may present with an acute flare and should always be considered in the differential of fulminant liver failure after all common cause have been excluded.[29,30] Presence of atypical histological features in form of centrilobular necrosis and absence of conventional antibodies or hypergammaglobulinemias may confuse the picture.[29]Corticosteroid therapy has been known to be effective in 36-100% of cases with fulminant presentations[29-31]. Careful selection of cases and complete assessment of an individual case even in the absence of classical features of AIH strongly argues for a trial of corticosteroids in deserving patients[31].

Nineteen patients in our series had a history of taking ayurvedic or anti-tubercular medicines prior to presentation. Drug-induced liver injury, commonly described with minocycline can mimic classical autoimmune hepatitis[32]. Antitubercular drugs like rifampicin, pyrazinamide as well as indigenous herbal preparations are known to cause a Type I AIH like illness[33,34]. Drug-induced autoimmune like hepatitis needs careful history and close assessment after drug withdrawal with a short course of corticosteroid therapy is useful for recovery. Drug-induced self-perpetuating autoimmune hepatitis requires the consideration of previous unsuspected AIH or latent AIH activated by drug or de novo AIH triggered by the drug[32].

Steroids and/or azathioprine have been the standard treatment for AIH. Recently budesonide has been shown to induce remission more effectively than prednisone in noncirrhotic patients with AIH[35]. The role of mycophenolate in the management of AIH and overlap syndrome is being investigated [36]. Early predictors and endpoints of immunosuppressive therapy are normalization of ALT, gamma globulins, serum IgG and normal histology[37,38].In our study majority of the patients treated with steroids, steroids + Azathioprine was the next most common mode of immunosuppression, while budesonide was used only in few non-cirrhotic patients andmycophenolate was used as a rescue therapy. Overall treatment response in decompensated patients was 73%. ALT normalization was the treatment goal and failure to normalize ALT within 12 months was associated with a higher hazard ratio of developing liver related death or transplantation Mortality rate at the end of first decade was 11%. Treatment end point in AIH should be strictly based on biochemical, immunological and histological normalization [39]. We could stop the treatment based on these criteria in some patients. We documented reversal of cirrhosis and normalization of histology in 5 patients. Relapse after stopping the treatment was seen in almost 40% of the patients in whom treatment was withdrawn. However, in most of these patients, histological remission had not been documented. In absence of documented histological remission, decision to withdraw immunosuppression should be a guarded one in view of high relapse rates.

Thus to conclude, AIH incidence is gradually increasing perhaps secondary to increased awareness of this disease. Though the mortality rates are higher when compared to normal age-matched population, long-term survival rates are significantly better even if there is decompensation at presentation. Liver transplantation though an accepted modality of treatment for decompensated cirrhosis, is still not widely available in India due to various constraints. In such a scenario, early diagnosis, appropriate treatment and adequate supportive treatment still forms a cornerstone of our AIH management.

References

- Czaja AJ, Freese D; American Association for the Study of Liver Disease. Diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2002;36:479–97.

- Hennes EM, Zeniya M, Czaja AJ,Hennes EM, Zeniya M, Czaja AJ, et al. Simplified diagnostic criteria for autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2008;48:169–76.

- Cancado ELR, Porta G. Autoimmune Hepatitis in South America. Kluwer Academic Publishers Dordrecht, Boston, London: 2000:2–92.

- Amarapurkar D, Patel ND. Autoimmune Hepatitis. ‘LIVER: A Complete Book on Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Diseases Published by Elsevier pp 249–60.

- Amarapurkar DN, Patel ND. Spectrum of autoimmune liver diseases in western India. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:2112–7.

- Gupta R, Agarwal SR, Jain M, Makhotra V, Sarin SK. Autoimmune hepatitis in Indian subcontinent: 7 years’ experience. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:1144–8

- Somani SK, Baba CS, Choudhuri G. Autoimmune liver disease in India: is it uncommon or underdiagnosed? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:A1054.

- Jain M, Rawal KK, Sarin SK. Profile of autoimmune liver disease in India. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 1994;13:A85.

- Gohar S, Desai D, Joshi A, Bhaduri A, Deshpande R, Balkrishna C, et al. Autoimmune hepatitis: a study of 50 patients. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2003;22:140–2.

- Balakrishnan C, Mangat G, Kalke S, Desai D, Joshi A, Deshpande RB, et al. The spectrum of chronic autoimmune hepatitis. J. Assoc Physicians India. 1998;46:431–5.

- Amarapurkar DN, Amarapurkar AD “Role of autoimmunity in nonviral chronic liver disease. J Assoc Physicians India. 2000:48:11:1064–9.

- Cook GC, Mulligan R, Sherlock S. Controlled prospective trial of corticosteroid therapy in active chronic hepatitis. Q J Med. 1971;40:159–85.

- Kanzler S, Lohr H, Gerken G, Galle PR,Lohse AW. Long term management and prognosis of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH); a single center experience. Z Gastroenterol. 2001;39:339–41, 344-8.

- Feld JJ, Dinh H, Arenovich T, Marcus VA, Wanless IR, Heathcote EJ. Autoimmune hepatitis: Effect of symptoms and cirrhosis on natural history and outcome. Hepatol. 2005;42:53–62.

- Johnson P, McFarlane I, Williams R. Azathioprine for long-term maintenance of remission in autoimmune hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:958–63.

- Strassburg CP, Manns MP. Treatment of Autoimmune Hepatitis. Semin Liver Dis. 2009;29:273–85.

- Czaja AJ Difficult treatment decisions in autoimmune hepatitis. World J Gastroenterol.2010;16:934–47.

- Sarin SK, Kumar A, Almeida JA, Chawla YK, Fan ST, Garg H, et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: consensus recommendations of the Asian Paciûc Association for the study of the liver (APASL). Hepatol Int. 2009;3:269–82.

- Alvarez F, Berg PA, and Bianchi FB, Bianchi L, Burroughs AK, Cancado EL, et al. International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group Report: review of criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1999;31:929–38.

- Manns MP, Czaja AJ, Gorham JD, Krawitt EL, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D, et al. Practice Guidelines of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;51:2193–213.

- Gleeson D, Heneghan MA. British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) guidelines for management of autoimmune hepatitis. Gut. 2011;60:1611–29.

- Czaja AJ. Review article: the management of autoimmune hepatitis beyond consensus guidelines. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:343–64.

- Boberg KM. Prevalence and epidemiology of autoimmune hepatitis. Clin Liver Dis. 2002;6:635–47.

- Czaja AJ. Autoantibody-negative autoimmune hepatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:610–24.

- Maheshwari A, Thuluvath PJ. Cryptogenic cirrhosis and NAFLD: are they related? Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:664–8.

- Czaja AJ. Cryptogenic chronic hepatitis and its changing guise in adults. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:3421–38

- Liberal R, Grant CR, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D. Autoimmune hepatitis: A comprehensive review. J Autoimmun. 2013;41:126–39

- Björnsson E, Talwalkar J, Treeprasertsuk S, Neuhauser M, Lindor K. Patients with typical laboratory features of autoimmune hepat6itis rarely need a liver biopsy for diagnosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011:9:57–63.

- Miyake Y, Iwasaki Y, Terada R, Onishi T, Okamoto R, Sakai N, et al. Clinical characteristics of fulminant-type autoimmune hepatitis: an analysis of eleven cases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:1347–53.

- Nikias GA, Batts KP, Czaja AJ. The nature and prognostic implications of autoimmune hepatitis with an acute presentation. J Hepatol. 1994;21:866–71.

- Ichai P, Duclos-Vallée JC, Guettier C, Hamida SB, Antonini T, Delvart V, et al. Usefulness of corticosteroids for the treatment of severe and fulminant forms of autoimmune hepatitis. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:996–1003.

- Czaja AJ. Drug induced autoimmune like hepatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:958–76.

- Lewis J, Zimmerman H: Drug-induced autoimmune liver disease. In Autoimmune Liver Diseases. Krawitt EL, Wiesner RH, Nishioka (Eds.). New York, Elsevier Science BV, 1998,pp627–649

- Kamiyama T, Nouchi T, Kojima S, Murata N, Ikeda T, Sato C.Autoimmune hepatitis triggered by administration of an herbal medicine. Am J Gastroenterol 1997;92:703–4.

- Manns MP, Woynarowski M, Kreisel W, Lurie Y, Rust C, Zuckerman E, et al. Budesonide induced remission more effectively than prednisone in a controlled trial of patients with autoimmune hepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2010:139:1198–206.

- Baven-Pronk AM, Coenraad MJ, van Buuren HR, de Man RA, van Erpecum KJ, Lamers MM, et al. The role of mycophenolatemofetil in the management of autoimmune hepatitis and overlap syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011:34:335–43.

- Montano-Loza A, Carpenter HA, Czaja AJ, Improving the end point of corticosteroid therapy in Type 1 autoimmune hepatitis to reduce the frequency to relapse. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;102:1005–12.

- Yeoman AD, Westbrook RH, Zen Y, Maninchedda P, Portmann BC, Devlin J, et al. Early predictors ofcorticosteroid treatment failure in icteric presentations of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2011;53:926–34.

- Manns MP, Strassburg CP. Therapeutic strategies of autoimmune hepatitis. Dig Dis. 2011;29:411–5.

- Krawitt EL. Autoimmune hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:54–66.

|

|

|

|

|

|