|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Original Articles |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

Parkinson’s disease, gastrointestinal symptoms, dysphagia, sialorrhea, aspiration |

|

|

Owolabi LF,1 Samaila AA,2 Sunmonu T3

Neurology Unit,1and

Gastroenterology Unit,2

Department of Medicine,

Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital,

Bayero University, Kano, Nigeria.

Neurology Unit,3 Department of

Medicine, Federal Medical Centre,

Owo, Nigeria.

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Owolabi Lukman Femi

Email: drlukmanowolabi@yahoo.com

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.221

Abstract

Background and aim: In spite of the overwhelming emphasis on motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease(PD), a number of studies have revealed that the non-motor symptoms including gastrointestinal, psychiatric and sleep symptoms have a greater influence on the quality of life of many patients. This study aimed to determine the frequencies of gastrointestinal symptoms in PD patients in comparison to healthy controls and to evaluate the relationship between these GI symptoms and severity of PD.

Methods: This cross-sectional study was conducted over a 2-year period. Consecutive new patients of Parkinson’s disease were recruited at the neurology clinics of Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital (AKTH) and Murtala Muhammad specialist hospital (MMSH).Healthy age and sex matched volunteers constituted the control group. A structured, pre-tested, close-ended questionnaire inquiring about common gastrointestinal symptoms as well as demographic, and PD characteristics was administered to all cases and controls. PD severity was assessed using the Hoehn and Yahr scale (H and Y).

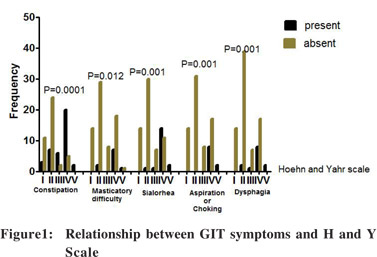

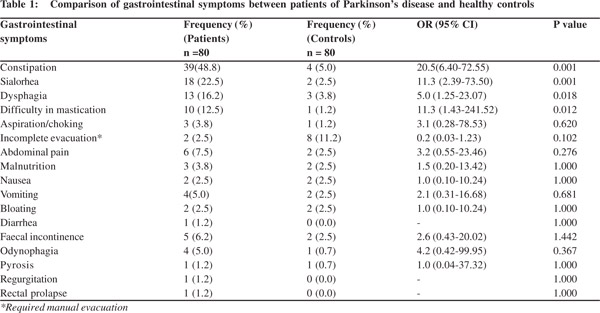

Results: A total of 80 patients and 80 controls were recruited during the study period. Their age ranged between 39 and 80 years. The mean age of the patients and controls were 61.1±8.5 and 61.0 ± 8.4 years, respectively. The male to female ratio was 5:2. The most common gastrointestinal symptoms were constipation (48.8%), sialorrhea (18%), dysphagia (16.2%), difficulty in mastication (12.5%), and choking/aspiration (12.5%).When compared with age and sex-matched controls the differences in the occurrence of these symptoms were statistically significant.Constipation, dysphagia, difficult mastication, sialorrhea, and aspiration/choking were found to be more severe on the H and Y scale.

Conclusion: Significant features of gastrointestinal dysfunction in PD include constipation, sialorrhea, dysphagia, difficult mastication and choking. These symptoms were significantly associated with increasing severity of Parkinson’s disease.

|

48uep6bbphidvals|678 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Parkinson’s disease (PD), a progressive neurological disorder, is the second most common neurodegenerative disease worldwide,[1,2]and a major illness in Nigeria.[3-5] PD was estimated to affect about 4.6 million people over the age of 50 years in 2005. It was projected that the burden of PD would double by 2030.[6]

The first description of Parkinson’s disease by James Parkinson in his essay on the “shaking palsy” in 1817 included gastrointestinal symptoms such as constipation and difficulty in swallowing.[7]Gastrointestinal dysfunction is one of several non-motor symptoms and complications in PD patients. In spite of the overwhelming emphasis on motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease, a number of studies have revealed that non-motor symptoms including gastrointestinal, psychiatric and sleep symptoms have greater influence on quality of life.[8]

Gastrointestinal symptoms affect the quality of life of many patients with PD.[9] Altered gastric and small intestinal transit may cause unpredictable absorption of medication further aggravating the classical motor symptoms of PD.[9] The severity of gastrointestinal dysfunction in PD is often closely associated with progression of the disease in general.9 Although, it is generally recognized that the clinical spectrum of PD is broader than its defining motor aspects, non-motor symptoms including gastrointestinal symptoms are routinely not assessed in the clinic.[9] However, most of these gastrointestinal complications of PD are treatable. Improved recognition can lead to more comprehensive management of the disease, and help improve patient quality of life. This study was conducted to determine the incidence of gastrointestinal symptoms in PD in comparison to healthy controls and to evaluate the relationship between these GI symptoms and severity of PD.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study conducted over a 2-year period, newly diagnosed consecutive patients with Parkinson’s disease were recruited at the neurology clinics of Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital (AKTH) and Murtala Muhammad specialist hospital (MMSH).PD was clinically diagnosed in accordance to the clinical criteria of the United Kingdom Parkinson Disease Society Brain Bank.[10] Healthy age and sex matched volunteers constituted the control group.

A structured, pre-tested, close-ended questionnaire inquiring about common gastrointestinal symptoms as well as demographic and PD characteristics including age at onset, initial symptoms and distribution of symptoms, disease duration and clinical features, was administered to all cases and controls. Among others, symptoms evaluated included dysphagia, constipation, vomiting, diarrhea, odynophagia and difficulty in mastication. PD severity was assessed using the Hoehn and Yahr Scale. All patients and controls were on typical Nigerian diet which is usually based around a starchy staple made from maize/corn, wheat, yams, cassava and rice.

Data analysis was carried out using SPSS v16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Mean and standard deviation were used to describe quantitative variables. Bivariate analysis was carried out using the Pearson’s Chi square or Fisher exact test for categorical variables. Chi square for trend was used to find the relationship between the most common gastrointestinal complications and increasing severity on the H and Y scale. Student’s t test was used to compare the means of continuous variables. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 80 patients and 80 controls were recruited during the study period. Their age ranged between 39 and 80 years. The mean age of patients and controls was 61.1±8.5 and 61.0± 8.4 years, respectively. The difference in their mean age was not statistically significant (p= 0.9). The patients and controls comprised 58 (72.5%) males and 22 (27.5%) females with a male to female ratio of 2.6. The median duration of PD was 2 years. None of the patients had persistent or recurrent gastrointestinal symptoms prior to the onset of PD.

The most common gastrointestinal symptoms were constipation (48.8%), sialorrhea (18%), dysphagia (16.2%), difficulty in mastication (12.5%) and choking/aspiration (12.5%).When compared to occurrence of these symptoms among age and sex-matched controls, their differences were statistically significant (Table 1).There was no statistically significant difference in the occurrence of incomplete evacuation, abdominal pain, malnutrition, nausea, vomiting, bloating and faecal incontinence odynophagia, rectal prolapse and requirement of manual evacuation between the cases and controls (Table 1). Constipation, dysphagia, difficulty in mastication, sialorrhea, and aspiration/choking were associated with increased disease severity on the H and Y scale (Figure 1).

Discussion

In this study, constipation was the most prominent gastrointestinal symptom. This finding agrees with other reports on gastrointestinal complications in PD.[11,12]The basis for normal gastrointestinal transport is coordinated contraction of smooth muscle cells. The autonomic nervous system is responsible for regulating smooth muscle activity. A defect in this system may cause constipation. There has also been an indication that constipation in PD is associated with vagal dysfunction.[13] The frequency of contraction of the gastrointestinal wall is determined by the interstitial Cells of Cajal, frequently alluded to as the gastrointestinal pacemaker cells.[9] Local reflexes and gastrointestinal smooth muscle contraction are under the control of the enteric nerve system, comprising large number of cells and large number of dopaminergic and non-dopaminergic neurotransmitters within the gastrointestinal wall. Dopamine is known to inhibit cholinergic transmission via D2 receptors.[14,15] In addition, certain inclusion bodies, “Levi bodies”, have been identified in the enteric nervous system of patients with PD.[16]Singaram et al has also shown a reduction in the concentration of dopamine in the colon in PD.[17] Thus, enteric neurodegeneration may be involved, as part of the multisystem involvement in PD and in the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal dysfunction in PD.[9] In our study, sialorrhea appeared a frequent gastrointestinal symptom, only second to constipation. This finding conforms to previous reports, and in fact, some workers have shown that PD is the most common cause of sialorrhea[18] with 70–80% of PD patients demonstrating sialorrhea.[19]Sialorrhea can cause social embarrassment, and because saliva pools in the mouth, it may lead to aspiration pneumonia. Sialorrhea in PD is thought to be caused by impaired or infrequent swallowing, rather than hypersecretion of saliva.[20] Disturbance in the coordination of orofacial and palate—lingual musculature is one mechanism that can lead to pooling of saliva in the anterior portion of mouth. Ultimately, muscle incoordination inhibits the initiation of the swallow reflex, further disrupting the path of saliva from the mouth to oropharynx.[21]

Discussion

In this study, constipation was the most prominent gastrointestinal symptom. This finding agrees with other reports on gastrointestinal complications in PD.[11,12]The basis for normal gastrointestinal transport is coordinated contraction of smooth muscle cells. The autonomic nervous system is responsible for regulating smooth muscle activity. A defect in this system may cause constipation. There has also been an indication that constipation in PD is associated with vagal dysfunction.[13] The frequency of contraction of the gastrointestinal wall is determined by the interstitial Cells of Cajal, frequently alluded to as the gastrointestinal pacemaker cells.[9] Local reflexes and gastrointestinal smooth muscle contraction are under the control of the enteric nerve system, comprising large number of cells and large number of dopaminergic and non-dopaminergic neurotransmitters within the gastrointestinal wall. Dopamine is known to inhibit cholinergic transmission via D2 receptors.[14,15] In addition, certain inclusion bodies, “Levi bodies”, have been identified in the enteric nervous system of patients with PD.[16]Singaram et al has also shown a reduction in the concentration of dopamine in the colon in PD.[17] Thus, enteric neurodegeneration may be involved, as part of the multisystem involvement in PD and in the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal dysfunction in PD.[9] In our study, sialorrhea appeared a frequent gastrointestinal symptom, only second to constipation. This finding conforms to previous reports, and in fact, some workers have shown that PD is the most common cause of sialorrhea[18] with 70–80% of PD patients demonstrating sialorrhea.[19]Sialorrhea can cause social embarrassment, and because saliva pools in the mouth, it may lead to aspiration pneumonia. Sialorrhea in PD is thought to be caused by impaired or infrequent swallowing, rather than hypersecretion of saliva.[20] Disturbance in the coordination of orofacial and palate—lingual musculature is one mechanism that can lead to pooling of saliva in the anterior portion of mouth. Ultimately, muscle incoordination inhibits the initiation of the swallow reflex, further disrupting the path of saliva from the mouth to oropharynx.[21]

Our study also showed that a significant number of patients with PD experience dysphagia. In other studies abnormal swallowing was found in 50 to 95% of PD patients.[22,23]However, the incidence in our study is lower possibly because we focused on newly diagnosed anti-parkinson drug-naïve patients. Swallowing dysfunction has been found to occur from the earliest stages of Parkinson’s disease, even in

asymptomatic cases.[24,25] Studies have consistently indicated that objective changes, including silent aspiration, precede subjective complaints of dysphagia.[24,25]Dysphagia in PD is said to be mainly due to insufficient cricopharyngeal relaxation and reduced oesophageal peristalsis.[23,26] Insufficient chewing due to stiffness of the masticatory muscles may also contribute.[23,26]

This may account for why difficulty in mastication was also common among our PD patients. Dysphagia requires a great deal of medical attention because it is associated with increased morbidity and mortality[27,28] and may place a considerable social and psychological burden upon the patients and their families.[29] Besides, for many PD patients, drinking and eating are already constrained by severe hand tremor and rigidity.

Aspiration and choking appeared one of the most common gastrointestinal symptom in our study.This finding conforms with previous reports and in many of these studies dysphagia was reported as the main cause of aspiration and death in PD.[30,31]Similar to our findings, several studies have confirmed that gastrointestinal symptoms are strongly associated with increased severity of PD as assessed by the Hoen and Yahr scale.[22,26] In fact, there is an indication that gastrointestinal symptoms may predate and possibly predict occurrence of PD. A large population based study in America conducted on middle age men showed that men with bowel motion less than once per day had a 2.7-fold risk of developing PD within the next 24 years in comparison with those with daily bowel motion.[32]In an attempt to increase general awareness among physicians caring for these patients, this study focused on the common gastrointestinal symptoms experienced by PD patients.It is, however, noteworthy that the list is by no means exhaustive.

In conclusion, gastrointestinal dysfunction is frequent in Parkinson’s disease. Significant features of gastrointestinal dysfunction include constipation, sialorrhea, dysphagia, difficulty in mastication and choking. These symptoms were significantly associated with increasing severity of Parkinson’s disease.

References

- de Lau LM, Breteler MM. Epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:525–35.

- Alves G, Forsaa EB, Pedersen KF, DreetzGjerstad M, Larsen JP. Epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol. 2008;255Suppl 5:18–32.

- Osuntokun BO, Adeuja AO, Schoenberg BS, Bademosi O, Nottidge VA, Olumide AO, et al. Neurological disorders in Nigerian Africans: a community-based study. ActaNeurol Scand. 1987;75:13–21.

- Okubadejo NU, Ojo OO, Oshinaike OO. Clinical profile of parkinsonism and Parkinson’s disease in Lagos, Southwestern Nigeria. BMC Neurol. 2010;10:1.

- Femi OL, Ibrahim A, Aliyu S. Clinical profile of parkinsonian disorders in the tropics: Experience at Kano, northwestern Nigeria. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2012;3:237–41.

- Dorsey ER, Constantinescu R, Thompson JP, Biglan KM, Holloway RG, Kieburtz K, et al. Projected number of people with Parkinson disease in the most populous nations, 2005 through 2030. Neurology. 2007;68:384–6.

- Parkinson J. An Essay on the Shaking Palsy. London: Whittingham and Rowland for Sherwood, Neely and Jones; 1817.

- Chaudhuri KR, Healy DG, Schapira AH, National Institute for Clinical E. Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease: diagnosis and management. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:235–45.

- Krogh K. Gastrointestinal dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. In:RanaAQ, editor. Symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. InTech; 2011. ISBN: 978–953–307–464-1.

- Litvan I, Bhatia KP, Burn DJ, Goetz CG, Lang AE, McKeith I, et al. Movement Disorders Society Scientific Issues Committee report: SIC Task Force appraisal of clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinsonian disorders. Mov Disord. 2003;18:467–86.

- Edwards LL, Pfeiffer RF, Quigley EM, Hofman R, Balluff M. Gastrointestinal symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 1991;6:151–6.

- Sakakibara R, Odaka T, Uchiyama T, Asahina M, Yamaguchi K, Yamaguchi T, et al. Colonic transit time and rectoanalvideomanometry in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:268–72.

- Wang SJ, Fuh JL, Shan DE, Liao KK, Lin KP, Tsai CP, et al. Sympathetic skin response and R-R interval variation in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 1993;8:151–7.

- Walker JK, Gainetdinov RR, Mangel AW, Caron MG, Shetzline MA. Mice lacking the dopamine transporter display altered regulation of distal colonic motility. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2000;279:G311–8.

- Anlauf M, Schafer MK, Eiden L, Weihe E. Chemical coding of the human gastrointestinal nervous system: cholinergic, VIPergic, and catecholaminergic phenotypes. J Comp Neurol. 2003;459:90–111.

- Wakabayashi K, Takahashi H, Ohama E, Ikuta F. Parkinson’s disease: an immunohistochemical study of Lewy body-containing neurons in the enteric nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 1990;79:581–3.

- Singaram C, Ashraf W, Gaumnitz EA, Torbey C, Sengupta A, Pfeiffer R, et al. Dopaminergic defect of enteric nervous system in Parkinson’s disease patients with chronic constipation. Lancet. 1995;346:861–4.

- Volonte MA, Porta M, Comi G. Clinical assessment of dysphagia in early phases of Parkinson’s disease. Neurol Sci. 2002;23Suppl 2:S121–2.

- Glickman S, Deaney CN. Treatment of relative sialorrhoea with botulinum toxin type A: description and rationale for an injection procedure with case report. Eur J Neurol. 2001;8:567–71.

- Chou KL, Evatt M, Hinson V, Kompoliti K. Sialorrhea in Parkinson’s disease: a review. Mov Disord. 2007;22:2306–13.

- Myer CM, 3rd. Sialorrhea. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1989;36:1495–500.

- Bushmann M, Dobmeyer SM, Leeker L, Perlmutter JS. Swallowing abnormalities and their response to treatment in Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 1989;39:1309–14.

- Nowack WJ, Hatelid JM, Sohn RS. Dysphagia in Parkinsonism. Arch Neurol. 1977;34:320.

- Nilsson H, Ekberg O, Olsson R, Hindfelt B. Quantitative assessment of oral and pharyngeal function in Parkinson’s disease. Dysphagia. 1996;11:144–50.

- Potulska A, Friedman A, Krolicki L, Spychala A. Swallowing disorders in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2003;9:349–53.

- Eadie MJ, Tyrer JH. Radiological Abnormalities of the Upper Part of the Alimentary Tract in Parkinsonism. Australas Ann Med. 1965;14:23–7.

- Johnston BT, Li Q, Castell JA, Castell DO. Swallowing and esophageal function in Parkinson’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1741–6.

- Wang X, You G, Chen H, Cai X. Clinical course and cause of death in elderly patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Chin Med J (Engl). 2002;115:1409–11.

- Clarke CE, Gullaksen E, Macdonald S, Lowe F. Referral criteria for speech and language therapy assessment of dysphagia caused by idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neurol Scand. 1998;97:27–35.

- Fernandez HH, Lapane KL. Predictors of mortality among nursing home residents with a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Med Sci Monit. 2002;8:CR241–6.

- Gorell JM, Johnson CC, Rybicki BA. Parkinson’s disease and its comorbid disorders: an analysis of Michigan mortality data, 1970 to 1990. Neurology. 1994;44:1865–8.

- Abbott RD, Petrovitch H, White LR, Masaki KH, Tanner CM, Curb JD, et al. Frequency of bowel movements and the future risk of Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 2001;57:456–62.

|

|

|

|

|

|